Related Tags

The history of Denmark Street, London’s music epicentre

From Tin Pan Alley to a guitar-shopping destination par excellence, London’s Denmark Street is a key part of the city’s musical history. As the street prepares to enter a new phase, we look back on its iconic past.

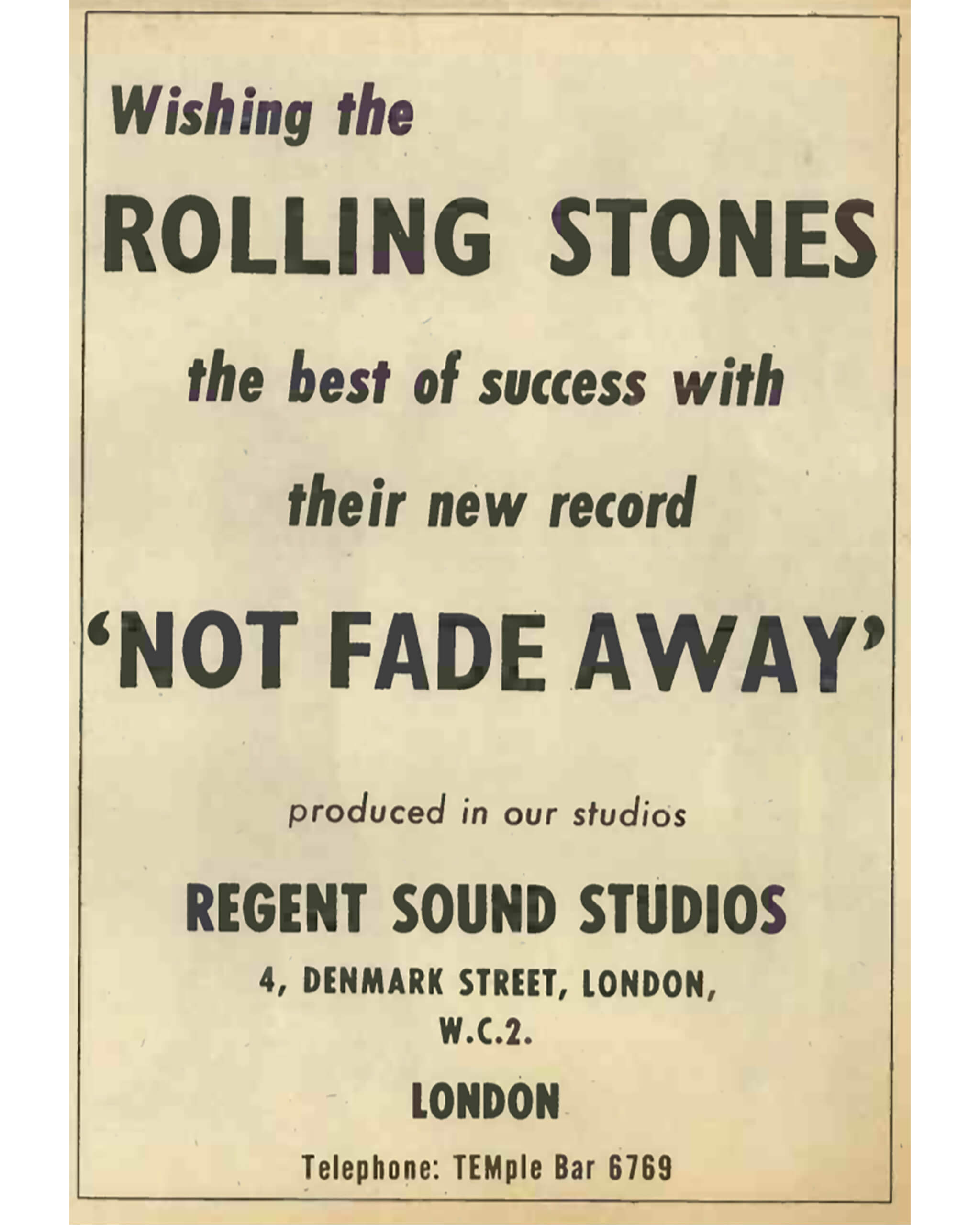

Crispin Weir stands proudly at the entrance to his Regent Sounds Studio shop at number 4, 2020. Image: Tony Bacon

Let’s take a walk down Denmark Street today. Turn the corner from Charing Cross Road in central London, and you’re in a hundred yards of history. But right now, you’d do well to have a hard hat handy. The street is under siege from a massive redevelopment, and the Crossrail development already engulfs a good deal of the surrounding area. Denmark Street is in the process of transformation.

Continue your walk, and as you carefully dodge the builders’ trucks and navigate the pedestrian diversions, you might just manage to catch a whiff of the historical importance of the place, especially if you have a vivid imagination and an eye for architectural detail. Now, though, some premises are boarded up, and most of the shops that are open have had their working lives almost literally turned upside down.

Through the years, Denmark Street has had at least three important musical lives. The first, lasting from the 19th century well into the late 20th, was as the home of the professional song business. The second, and the one we’re most interested in, began in the mid-60s as the street started to attract music-shop owners, and into the following decades it thrived as a key destination for guitarists and would-be players.

The third of Denmark Street’s lives is under way now and planned for the near future. Once the dust has settled, the street frontages will remain, but there will be a series of new venues and still, hopefully, plenty of guitar shops.

Pete Townshend complained to a London newspaper, saying: “In the 60s, I bought fuzzboxes and strings for my guitars from Macari’s guitar shop in Denmark Street. The Who did a backing-vocal rehearsal with Shel Talmy in Denmark Street at Regent Sound in 1964. I used to shop at the Drum Store when living in nearby Wardour Street, Soho. Boris Johnson [London mayor at the time of Pete’s letter] and Camden Council, please make Denmark Street a Heritage Zone. Otherwise a massive chunk of rock music history will be lost forever. Progress is important, but so are the local landmarks of our great city.”

The ‘Save Tin Pan Alley’ campaign said: “There is no equivalent anywhere in the world! Let’s celebrate this wonderful place and bring even more music back to Denmark Street in all of its vibrant diversity.”

The developer reckons the result of its efforts will be “a successful new quarter that will enrich and integrate with the surrounding well-established neighbourhood … and not only safeguard, but reinvigorate the area’s fantastic music and cultural scene”. Time will tell. Everything comes and goes.

Back in the day

Let’s take a walk down Denmark Street in the 1970s. The street had remained at the centre of the song business for some time, with many leading publishers in rooms and offices and cubbyholes up and down the street’s terraced buildings, the earliest of which date back to the 17th century. The inhabitants included old hands like Lawrence Wright (“You can’t go wrong with the Wright songs”) and Mills Music (where 17-year-old Elton John, still Reggie Dwight, once had a job making tea).

There were arrangers, copyists, musicians, too, and publications: Lawrence Wright started Melody Maker at number 19 in 1926 (soon relocating to Long Acre) and NME moved to number five in 1952 (also shifting to Long Acre, in ’64). Denmark Street became known as Tin Pan Alley, a reference to America’s original song-biz area in New York City, named for the racket made by so many pianists pounding out their potential hits.

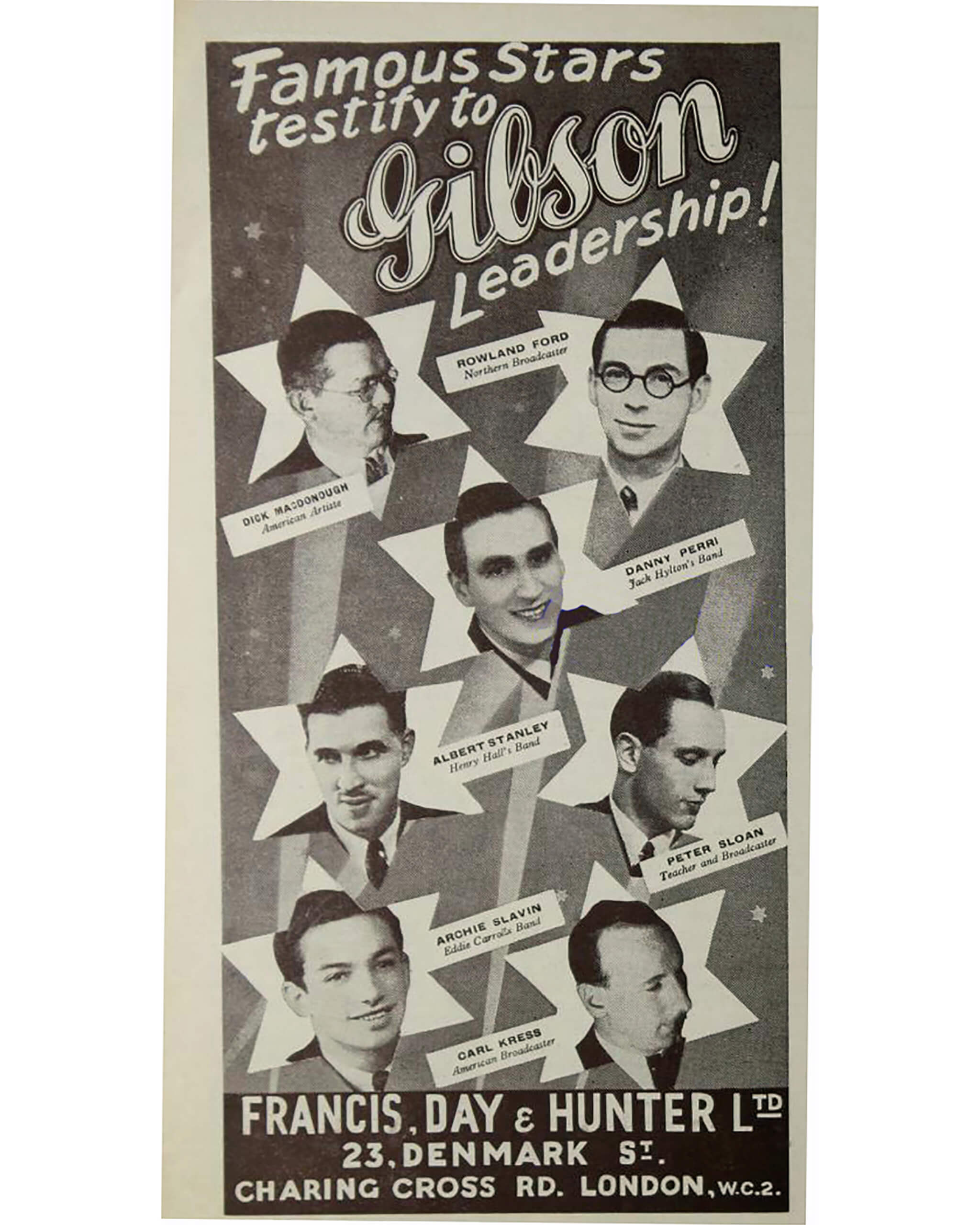

There were a few music shops in Denmark Street before the rock boom of the 60s and 70s – Francis Day & Hunter at number 23, for example, was advertising Gibson guitars in the 1930s – but probably the first we’d recognise as a proper guitar shop was Musical Exchange, run by Joe and Larry Macari, who already had a couple of shops in the north-west reaches of outer London. They knew, though, that the centre of town was the place to be, and they opened at number 22 in the early months of 1965. Gary Hurst reckoned it was in the back of this shop that he made the original Tone Bender fuzz boxes, and it was the Musical Exchange shop that marked an early start to a shift in the street’s business.

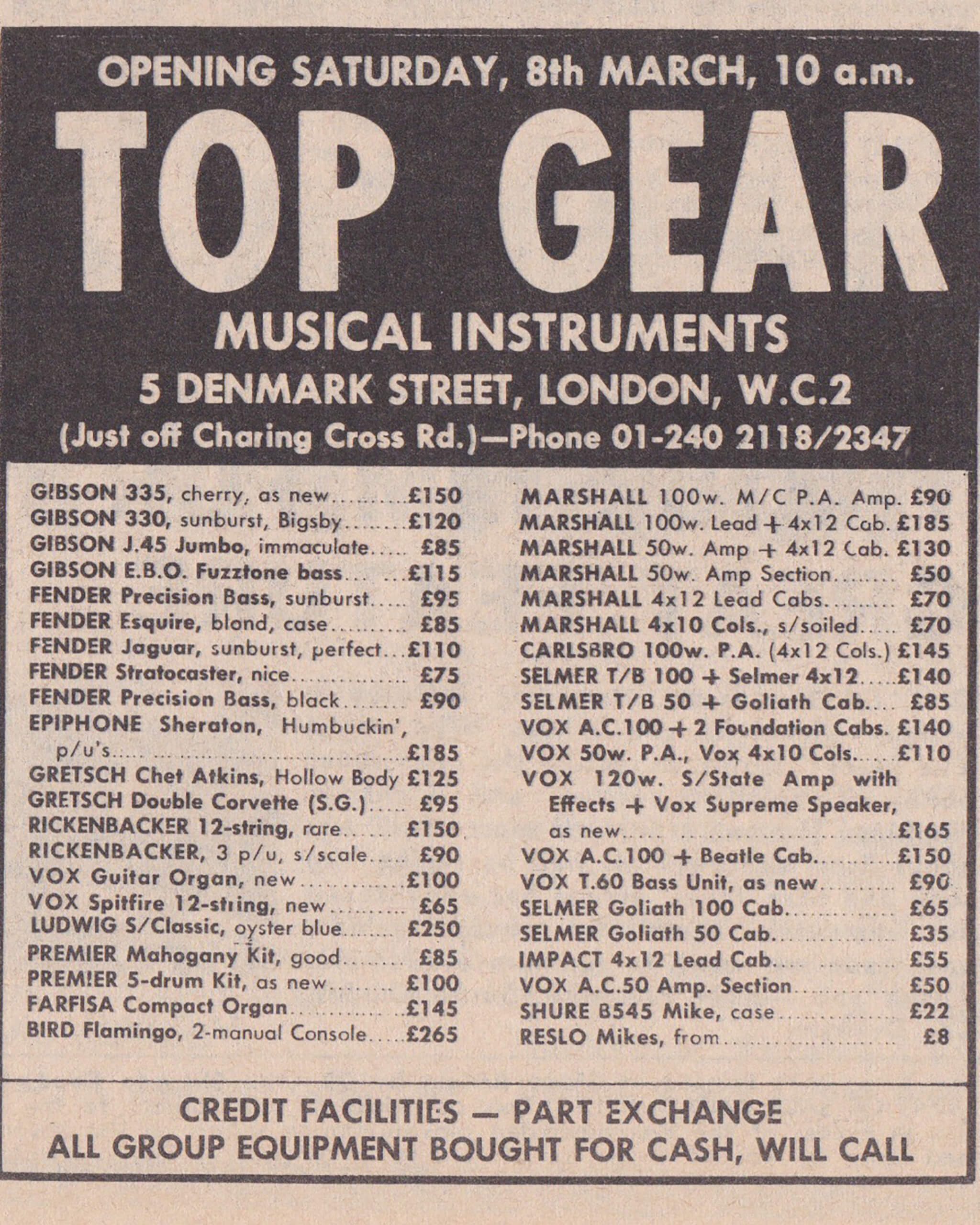

The next significant arrival was Top Gear, opened at number five by Craig and Rod Bradley in March 1969. Sid Bishop, ex-guitarist from Mick Farren’s band The Deviants, started there in 1971. Top Gear was untidy and scruffy, and that was part of its special charm. “If you’d gone into Sound City on Shaftesbury Avenue or Selmer’s on Charing Cross Road,” Sid says, “it was spotless. A lot of your hairy muso types would be put off going into a shop like that. Go into a place like Top Gear, and if anybody said anything wrong to me, they’d get a bloody mouthful.”

At first, what stock there was in Top Gear was all secondhand. “Rod and Craig couldn’t get accounts originally with the leading wholesalers for new guitars, so we depended on people coming into the shop and offering us stuff,” Sid continues. “There was no vintage collector’s market – that came later. So we’d buy an SG Junior for 50 quid and stick it on the wall for 95 quid. I’d buy a Firebird V for 200 quid and stick it on the wall for 300 quid. It was a nice atmosphere – Rod and Craig were fair guys.”

Top Gear was a social centre, too. Jimmy Page, Pete Townshend, Eric Clapton, Bernie Marsden, Mick Ralphs, Luther Grosvenor, all were regular visitors. Hank Marvin, too. “A lot of it was word of mouth,” Sid reckons. “Hank became a very good friend of ours, used to come in a lot. He never bought anything. He’d come in, have a cup of tea, have a chat, and sit down for a noodle. He was a lovely guy – but I don’t think he ever spent a penny in our shop.”

So who did? “Jimmy Page bought a Les Paul Custom, Chris Spedding, too, Micky Grabham a sunburst ’59 Standard,” Sid says, misty eyed. “Eddy Grant also bought a Standard, Marc Bolan a Custom, a Flying V, and a white Strat. Keith Richards bought a National resonator, an old Rickenbacker solidbody, a Les Paul Custom, and an Everly Brothers or a J-200, one or the other.”

“All i’m trying to do is balance running a good guitar shop with raising awareness of the history of the studio and the street as a wholE” – Crispin WEIR, REGENT SOUNDS

Bob Marley’s Les Paul Special was one among many guitars that passed through Top Gear. They bought it from Dan Armstrong and sold it on to Marc Bolan, but he was soon back for something with humbuckers, and swapped it for a Les Paul Custom. Then Bob Marley bought it, on his first UK tour in ’73. “He’d only had it a little while,” Sid says, “and it fell forward off a guitar stand – the selector switch punched right through the rhythm/treble surround. Bob brought it in, said look what I’ve done. Oh, you silly boy, Bob! We showed it to Roger Giffin in our back room, and he cut out and fitted a new surround. Gave it back to Bob, said here you are – you won’t do that again – and he was over the moon.”

Top Gear closed in 1978, as the Bradleys shifted efforts to their Strings & Things wholesale company, and number five became Roka’s, run by Top Gear’s amp fixer, Ron Roka. Sid worked briefly for Boogie Music and then went to Chappell’s in Bond Street until 1986. He moved to the States, working at Pete’s Guitars with Pete Alenov in Minneapolis–Saint Paul. These days he’s retired and living in Crete – and he’s written a so-far-unpublished book about Denmark Street.

Another beat boom

Let’s take a walk down Denmark Street in the 90s. Cliff Cooper was on something of a spree. He had the Orange shop in nearby New Compton Street, but that closed in ’78, and he opened Rhodes Music – apparently named after the explorer Cecil Rhodes — which was his first shop on Denmark Street, at number 22. “When I first went into the street, it was almost derelict and still nearly all music publishers,” Cliff recalls. “There was the Giaconda restaurant at number nine, where a lot of the bands hung out. They’d park in Denmark Street – no yellow lines in those days – sleep in their vans overnight, and play the Marquee the next night. Bedford vans everywhere!”

In 1989, he’d taken over a second shop in the street, number 21, as EMI moved its sound library out of the building, and he created the hi-tech Sutekina shop (sutekina means beautiful in Japanese), later renting the basement to Gibson for its London showcase. Come the 90s, and Cliff’s takeover quest saw him open in 1990 the PA Centre at 23, formerly the Forbidden Planet sci-fi and comics shop; Argent’s keyboard store at 20 (1992), turning it into a brass, woodwind, and sheet music shop; World Of Pianos at eight (’94); Hank’s acoustics kept at 24 (’95); Sutekina moved to 10 (’96), 21 becoming a second Rhodes Music, and a bass shop opened at 22; a drum and merchandise shop at 28 (’98), where Cliff locates his own office up in the crow’s nest on the fourth floor, while 23’s basement becomes auction rooms; and five floors at the Rose-Morris shop at number 11 (’99).

Cliff had turned Denmark Street into a sort of horizontal musical department store. “Each shop was a specialist shop,” he says. “And by now the street was getting so busy. It was great – it was just music everywhere.” The money was rolling in, too, hundreds of thousands a week, almost all in cash. “And there wasn’t a shortage of villains in that area,” Cliff adds, with a laugh. So he devised an ingenious cash transfer system, making the most of his run of shops on the north side from Hank’s at 24 to Argent’s at 20. They knocked holes through from shop to shop and put in a pneumatic pod-in-a-tube system. “We’d send all the money through up to Argent’s at the end, where it would be counted – and then we had to get it from there to the bank around the corner. We had three different people with bags, the money in one of them, and the other two were decoys. We really had to be careful in those days.”

Cliff came up with a plan in the 90s to buy Denmark Street. He had leases on a good deal of it anyway, so why not go for the lot? The freehold owner suggested a figure around £11 million. “I was going to pave it across and turn it into a music street, a real music-theme scene for the world. I couldn’t sleep at night I was so excited.” He got very close to raising the money, but was beaten to it by Consolidated Developments, which acquired the site in 1996 and is behind the current redevelopment work.

Meanwhile, Cliff was thinking about reviving Orange Amps, which had waned in the ’80s. In the late 90s, with the help of Adrian Emsley, he began to design a new range. “It was lucky,” he says, “because Noel Gallagher of Oasis came into one of my shops – he’d used Orange to record their first two albums – and he came looking for Orange amps. We introduced him to Adrian, and between us we came out with a design he wanted, shaped to the sound Noel wanted. He bought it and used it on television. That launched us again! So Orange was reborn in Denmark Street, designed in the back of number 22.”

With Orange’s new life to deal with, Cliff decided to sell up his Denmark Street shops, several of which went to Rick and Justin Harrison of Music Ground, and by 2006 Cliff had left the street altogether. Around 2000, Rick Harrison had acquired number five, turning Roka’s rather unsubtly into Rockers, and a little later started taking over other shops, including numbers 22, 23, 24, and 25 from Cliff, and also number four. Meanwhile, Chris Bryant took over a print shop at the corner of Charing Cross Road, and Wunjo went into number 20. Andy’s — a fixture at number 27 since the 70s and run by Andy Preston, a big influence on the street for years – became Music Ground, then Hank’s, which moved from 24. In the following years, Denmark Street continued to build its image as a magnet for visiting guitar fans.

Changing times

We’re back in Denmark Street today. And as anywhere, it’s hard work on many levels to keep a music shop going. Among the hoardings and hard hats, you can still see Wunjo (guitars) on the corner of Charing Cross Road; Music Room (sheet-music) at number 19; Westside MI (guitars) at 23; Hank’s (guitars) at 27; and Sixty Sixty Sounds (guitars) at 28. Over the road, there’s another Music Room and Stairway To Kevin (repairs) at number 11; Rose-Morris (guitars and drums at eight, pianos at 10); NO.TOM (guitars) at six; Wunjo again at five; and Regent Sounds (guitars) and Noden (repairs) at four. They battle daily with the redevelopment chaos, and at the time of writing there was also the uncertainty and restrictions of coronavirus to deal with.

Crispin Weir at Regent Sounds says the works are set to continue for at least another year or two, adding that the developers are very aware of and sensitive to the historical importance of the street. If they were going to turn it into wall-to-wall Starbucks, he says, they could have done that years before the redevelopment process started. Crispin’s understanding is that Laurence Kirschel, the owner of Consolidated Developments, wants to create a sort of music quarter.

“Like all landlords, they’re under huge pressure to make the development a success, and that will obviously involve a lot of commercialisation. It will mean significant change for the street, both good and bad. It remains to be seen whether the shops will be able to afford the future rents, but we hope the potential of Consolidated’s Outernet ‘immersive media space’ and the draw of the venues will be great for musicians and fans alike, hopefully giving us enough trade to keep going.”

Crispin grew up in London’s West End as a teenager, and like many he trod the boards and was stuck to guitar-shop windows. He started working at Regent Sounds in 2004 before he took over the shop six years later, and he’d become fascinated by the history of the place. Like most buildings on the street, it had a star-studded past, but perhaps no other building has quite the same significance as this former home of Regent Sound recording studio.

The studio was established in 1951, primarily as a demo studio and photographic studio for session musicians and the street’s publishing business – a requirement that prompted other studios to follow at number eight (Southern Music), nine (Central Sound), 21 (KPM, whose legendary “library music” instrumentals were recorded there), and 22 (Pan/TPA).

Regent went on to become one of London’s busiest studios. In the 60s, it was run by James Baring, who hired Bill Farley. Bill engineered the first Stones album, recorded in its entirety at Regent across a few days in early ’64, and most of the second LP there. “The first one was done all in England,” Keith Richards later told Rolling Stone magazine, “in a little demo studio in Tin Pan Alley, as it used to be called –Denmark Street in Soho. We used to think, ‘Oh, this is a recording studio, huh? This is what they’re like?’ A tiny little backroom.” The little room was good enough to conjure demos and records for everyone from Vera Lynn to Black Sabbath, from Petula Clark to Jimi Hendrix, from The Kinks to Bananarama, until it closed in the 1980s.

“[bands] would park on Denmark Street – there were no yellow lines in those days – sleep in their vans overnight and play the Marquee the next evening. Bedford vans everywhere!” – CLIFF COOPER, ORANGE AMPS CEO

After that, number four became a print shop for a while, and then in 1995 it opened as the Helter Skelter music bookshop. That lasted until 2003, and in the first weeks of the following year Rick Harrison opened it as the Regent Sounds Studio guitar shop. Crispin recalls a Russian oligarch who used to come in with his daughter. “She just pointed at stuff, and he’d go: ‘We take it,’ ‘We take it,’ ‘We take it.’ And basically he bought most of the shop. Sadly, that never happened again!”

These days, Crispin looks forward especially to Joe Walsh’s regular visits. “He walks along, and he puts his hand up to where a guitar’s on the wall, lifts it, and goes, ‘I won’t take that one.’ Next one, he lifts it, and goes, ‘I’ll take that one.’ Next one, ‘I’ll take that one,’ next one, ‘I won’t take that one.’ It’s like the scene out of Little Britain, ‘Want that one; don’t like that.’ It’s very entertaining. He’s a living legend.”

For Crispin, and for many more of the street’s fans, Denmark Street will only have a viable future – with its three new venues, fancy hotel, and all the rest – if the parties concerned manage to get it right. “All I’m trying to do,” Crispin says with commendable modesty, “is balance running a good guitar shop with raising awareness of the history of the studio and the street as a whole. It’s an incredibly special place, and I feel passionately about protecting it for future generations, until it’s my turn to hand the baton on, so to speak. It’s a difficult balancing act, running a business here, especially now – but trying to appeal to tourists, pro musicians, and beginners alike is a long tradition, and I’m honoured to be a part of it. The future of Denmark Street, to me, is a matter of trying to get the balance right for everybody.”

For more features, click here.