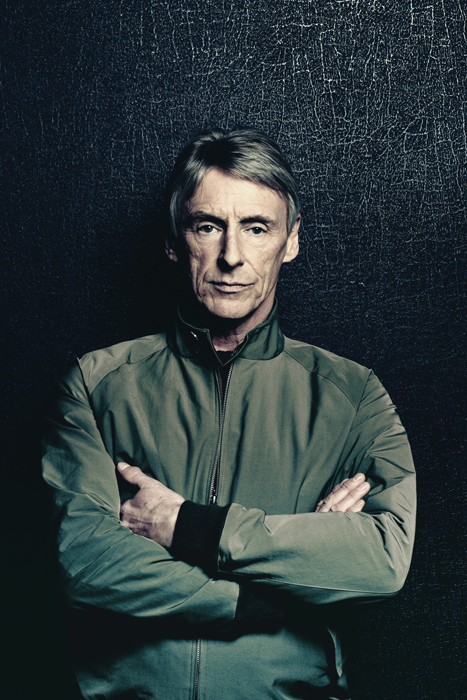

Interview: Paul Weller on Saturns Pattern, guitars and pushing boundaries

The Modfather’s 12th solo album finds the former Jam and Style Council man refusing to rest on his creative laurels and continuing to push stylistic boundaries.

‘‘Sorry about that, it just cut off,” Paul Weller apologises at the outset of our interview. He’s ringing me back after our first call went dead just as I was recounting one of our first meetings, in the early 90s. Given Weller’s reputation, I thought perhaps he’d hung up on me. “Nah, don’t be ridiculous,” Weller assures me. “It’s all good.”

Weller is calling from a dressing room in Berlin, in the middle of a brief European theatre tour ahead of the release of his 12th studio solo album, Saturns Pattern, having just wrapped up a “cracking” soundcheck.

“We went on a bit longer than usual ’cos it just sounded so good,” he confesses.

It’s not just soundchecks that are cracking these days for Weller. He’s in the midst of a creative purple patch that began with 2008’s 22 Dreams, released on the eve of his 50th birthday, and continued with Wake Up The Nation (2010) and Sonik Kicks (2012). Each was heralded for its far-reaching production techniques and songwriting, and Weller’s apparent lack of fear in trying just about anything, stylistically, he could think to tackle.

All the while, Weller kept up a gruelling touring schedule, and even found time enough to launch two seasons of a men’s clothing line – Real Stars Are Rare – and compile a book called Into Tomorrow, made up of photographs from his solo rebirth during the 90s Britpop era through to the present day. He also got married and had twins – John Paul and Bowie – to compliment his five other children.

However busy he is, Weller’s happy to talk about his creative process, songwriting techniques and his gear. At a time when a lot of his contemporaries have stopped making new music, or certainly new music that’s remotely different from what they’ve done before, Weller continues to push himself to release new material and challenge his creative process. We ask what fuels this spirit of restless invention, and whether – ultimately – he makes records for himself.

“Obviously, I do it because I love doing it,” he says. “But as a writer, you’re always looking to see what else you can write. Can you make this better? Can you do the quirkiest piece of work you’ve ever done? All those questions, really. It’s a never-ending quest, and I don’t think that you ever stop until you’re finished.”

We wonder whether Weller feels the need to make concessions to commercial accessibility in pursuit of that quest, or is testing creative new ground his sole concern?

“Well, essentially, I’m just doing what I need to do, which is to write and make music. That’s at the very core of what I’m about really. I’m quite happy living life like that. I still feel I’ve got loads of music inside me. Whenever I feel like that, I want to keep making it and see where it goes. I just think it’s fascinating, really, the twists and turns of this whole path. But yeah, I just want to keep on making more of it.

“The commercial aspect of it [the current musical landscape], it’s anyone’s guess, man. If I had the choice between selling a thousand or a million, I’d much rather sell a million, because it means I can get more money.”

“Outside of that, I’ve never really thought about what’s commercial. It’s just… I hope it’s all popular with people, because that’s what you should be doing. But in terms of whether it’s commercial, who knows, man? I don’t know who knows what’s commercial or not. I certainly don’t.”

When we were on hold, awaiting our audience with the Modfather, the record company had short snippets of its current hit songs playing on the line. Weller doesn’t sit neatly alongside some of his label-mates, so do these “hits” offend his aesthetic?

“I probably don’t judge it like that, I hope,” he replies. “I probably judge it solely on its merit. Or maybe not its merit, but on whether it affects me or not. Probably, a vast majority of the charts means nothing to me whatsoever, but I’d have said the same thing about the 70s and 80s, as well.”

“There was tons and tons of shit out there, but you had to look for something that meant something to you. I don’t know if it’s become too different.”

“I don’t think you can include the 60s, because it was such a different time. But there’s some great music out there. It’s inspiring to me to hear great music, whether that’s new or old, and it inspires me to go make great music. So I don’t slavishly follow what’s going on, but at the same time I’m interested to hear what’s going on as well.”

Saturns Pattern continues an adventurous approach to production that was present on 22 Dreams and Wake Up The Nation – and even more so on Sonik Kicks. We observe that the songs don’t necessarily feel as if Weller could still sit down and play them on an acoustic guitar or a piano, yet in a previous interview, he told us that was how his songwriting always began. It appears no longer to be the case.

“None of the new songs started out at that level, for sure,” Weller explains, with even the more traditional-sounding Where I Should Be resulting from sessions of sonic experimentation.

“It was all kinds of improvised and made up on the spot, to be honest with you. Because I had loads of songs, I had, I guess, six or eight tunes I’d written at home, but I chose not to use those. They didn’t feel right for the album I wanted to make. There wasn’t anything pre-planned on the album, it was just us experimenting with things to see what happened. So we ended up writing a lot of it in the studio.”

The latter approach became the norm during Weller’s work with former producer Simon Dine, but he stresses that he still enjoys adopting a back-to-basics approach for some of his writing.

“Well, I’ve worked with both methods. I like doing it like that, but also in a more traditional way, writing at home,” says Weller. “It’s whatever, really. I haven’t got a set plan anymore. Whatever way works.”

“I’m interested in whatever way that is, whatever method. I never really know where I’m going to go. It just takes me, really. I think it depends where I’m at. I always try to find different ways of doing things, just to keep it interesting.”

“I think the really important thing is just to keep an open mind about all of it. There isn’t any set way to making music or writing. It’s just whatever’s in the air at the time. The older you get, the more important it is to stay open-minded, I think, and not look at it as a fixed way of doing things. It’s whatever works, man.”

“I don’t think I’m going to work one way, or this way, or the other way. I’m into whatever, really: working with other people, writing with other people, just seeing where it goes.

“I feel really, at my age now, like I need to go on and try to take it as far as I possibly can, really, to carry on experimenting with other types of music, working in different ways. I think I’m at the right age to do that. I think it’s right at my age to try and see what else you can become, as opposed to just doing what’s expected of you.”

“There is no rulebook. That’s the thing of it. We sort of rip it up and don’t worry about it. That’s the beauty of it, really. Sometimes all the pieces come together and they don’t work, but that’s OK. You’ve got to be versatile with things as well.”

“I don’t have any career moves or ideas about what my ideas should be. I haven’t got a fucking clue. I just work at it from day to day and figure out a way to go along like all human beings do, really. That applies to life, as well.”

Weller’s desire to challenge himself may also lead to more collaborations and projects with younger artists.

“I really like that and I’d like to do some more,” says Weller. “I’d love to do some stuff in the States, as well, but I don’t know who with. I’d like too expand my horizons, really.”

When asked about his guitars, Weller replies mischievously: “I don’t know anything about ’em, but I’m willing to try,” before expanding on some of his old favourites – his 60s Epiphone Casino, SG and Tele.

“I’ve been playing them for god knows how long, but yeah, I know what I need to get out of a guitar, especially my SG,” he reflects, despite seemingly forever being associated with the Rickenbackers he played in The Jam, but no longer uses.

“It’s been a long time since I played one of them. I think it’s because the Casino and SG and Tele are very adaptable,” he says. “You

can get different tones and sounds out of them between the pickups. They’ve all got a certain versatility.”

How, then, did Weller come to fall in love with the Casino?

“By looking at The Beatles in 1966,” he admits. “The same reason I bought the SG. I saw George Harrison playing one around Revolver. Kind of, ‘Good enough for me!’”

And what of acoustic guitars? As one of the most consistently innovative songwriters in rock history, does Weller subscribe to the notion that acoustics have songs in them?

“No,” he replies in short. “But I wish I could find one of those ones, then. I’ve been using these new Guilds recently. They’re really nice. I don’t know what they cost, but they’re really nice guitars. Live as well, they’re really nice guitars.”

Weller played a 70s Gibson J-45 for many years, and it remains in his collection today. “It’s still around. It’s languishing in the studio, but it makes an appearance every now and then,” says Weller, who penned “five or six” acoustic-based songs in the writing sessions for Saturns Pattern that don’t appear on the new album. He tells Guitar & Bass that these are likely to appear on future releases.

“ I think they’ll probably come out as like B-sides or bonus tracks, that kind of thing. They’re good, not all of them, but some of them. I just didn’t want to make an album of acoustic songs. I wanted it to be more electric. But they will be coming out soon, yeah.”

As a guitarist, Weller welcomes the fulsome praise that comes his way from his peers, and has a long-lasting playing relationship with Ocean Colour Scene’s Steve Cradock, but he still confesses to some insecurities about his own playing.

“It’s a great compliment. It’s always nice to have some praise from your peers and fellow musicians,” says Weller. “I’m always pleased to hear that. I don’t always have an angle, really, on what my playing is like or not.”

“Sometimes, I go through periods where I feel like I’m not really going anywhere, and other times I feel like I’m better than I was 20 years ago. I go up and down a bit with it, really. But hopefully you’re just constantly learning.

“The thing with me and Steve is that he’s kind of telepathic sometimes. We’ve played music together for a long time, that’s true, but we also talk together about music quite a lot. I think there is a certain thing where we’re kind of comfortable and know what we’re doing, but at the same time I think we’re both trying to move it along a little bit and get more comfortable as well, always getting better.”

“It can also involve not playing as much. Sometimes it’s just leaving a bit more space. Whatever it may be, I think we’re both conscious of trying to think about what we’re doing and whether we can improve it.”

Weller, who says he hasn’t recorded on tape for “probably 10 years”, also acknowledges the importance of studio technology and software such as Pro Tools in keeping his music vibrant and at the cutting edge.

“Yeah, that’s pretty incredible, all that. I don’t actually work in any of that stuff, I’m relying on other people. But I think some of the edits and arrangements we did on the new album you simply couldn’t do on tape. I think this album kind of came into its own through working on Pro Tools.”

“We do try layers of stuff. But when you hear the finished thing, you only hear what we kept. There’s plenty of things we try and then ditch, to move it along. Different arrangements, different instruments, until we end up with what we’ve got.”

“I think we turned up one day when we were going to start the sessions for As Is Now, and we couldn’t get any multitrack. There was no tape. I think Ampex had just gone out of business, so you couldn’t buy a reel of tape. It was kind of the writing on the wall, really. Tape’s so expensive now, as well.”

“You don’t really have too much choice after a while. I wasn’t happy when they said they were going to put one of my albums on a CD 30 years ago. I was really upset. ‘What’s wrong with records, man?’ But look, whatever it is – progress – you you can’t stop it anyway.”

“It’s difficult, because I love the old analogue sounds, but ultimately your music ends up digitised. We’re very conscious of it and try to add as much analogue warmth and intimacy as possible. We all grew up with that. At the same time, it’s like any technology: there are always some good bits and some shitty bits. You’ve got to take the best bits that are most useful to your sonics.”