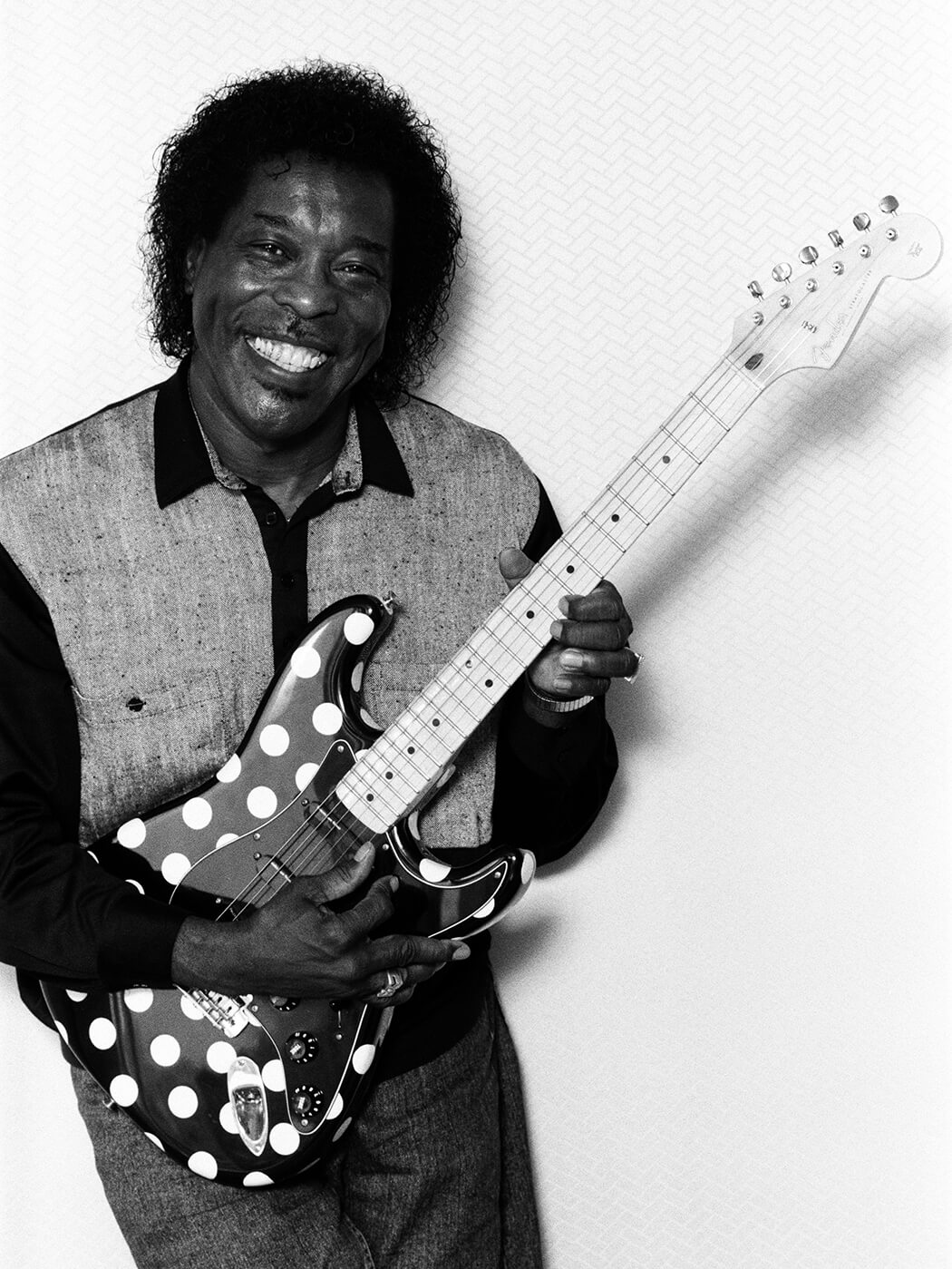

“I don’t want to become an endangered species”: Buddy Guy

Buddy Guy is a living legend of blues guitar, but despite his myriad plaudits and awards over the years, he remains a guitarist’s guitarist who only really cares about preserving and furthering the music he l oves.

Image: Edu Hawkins / Redferns via Getty Images

This interview was originally published in 2006.

They don’t call Chicago the Windy City for nothing. In January, the Arctic-like gale howls in over the lake with a vengeance, plunging the city into impossibly cold sub-zero temperatures. In summer, the wind is still there, but as much as the breeze cools the lakeshore tower blocks, by the time it reaches places like the funky old Chess Records building down on South Michigan avenue, it’s just a rough blast of dust.

Chicago’s certainly always been a tough place to survive, and this is never more true than for a bluesman. The dozens of small, smoky, sweat-drenched clubs – places like Theresa’s, Florence’s and the 1815 – that once offered a regular gig to musicians like Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Junior Wells, Elmore James and the hundreds that came after them are long gone. Of course, the blues is still there, but most visitors who still visit the city as musical pilgrims will probably find it in sanitised uptown joints like Blue Chicago and, if they’ve got any sense, Buddy Guy�’s Legends.

Legends is situated a short cab ride from downtown Chicago, and from the outside, there’s little to distinguish it from many other clubs. Step inside, however, and there’s a palpable sense of history. The walls are covered with memorabilia, alongside photos of the owner and the legendary names that regularly performed there – Stevie Ray Vaughan was on his way to the club for a late-night jam the night he died – and it’s really like nowhere else. Once inside, you just can’t wait for showtime.

But then Buddy Guy’s no newcomer to the club business. Before starting Legends, he owned the Checkerboard Lounge, one of the legendary Chicago hangouts and a place that will always have a place in rock history. In 1981, The Rolling Stones unexpectedly jammed there with Muddy Waters, and some think the bootleg DVD of the occasion shows that, while Keef and Ron Wood might have picked up a good deal about the blues, they’re still not quite Muddy Waters.

Feeling at home

Every January, Buddy takes time off touring to host shows at the club. It’s a long-standing tradition and, as he explains, one he absolutely loves.

“I finished the night before last, and as long as the people enjoy it I’ll go on doing it,” he affirms. “Music for me is all about making someone happy, and I always enjoy that. I love to see someone smiling, and hope that I made them forget about other things for a while.”

There’s been a long tradition of blues players owning clubs: even BB King now has a chain throughout the States. It’s good business, with one big advantage: if you own a place, you’ve always got a gig.

“I think I was the first guy to have a club,” Buddy reflects. “Back in 1972, there were blues clubs all over Chicago, but after the riots, they disappeared. Drugs took over and people weren’t drinking and listening to the music any more. All over town, there were clubs closing and I was thinking: ‘Where’s the next Eric Clapton, BB King or Muddy Waters going to be heard?’. I just got my life savings and decided that I was going to open my own. I wasn’t looking for a big profit and even today, I don’t make a lot of money from Legends, but I have a lot of fun watching other people play.”

And it’s true – when he’s not spreading his own particular brand of the blues gospel around the world, there’s nothing more Buddy enjoys than just hanging out at the club checking out the action, and visitors are often surprised to find the boss perched on a bar stool holding court and listening to the band.

“I’m not one of those performers that the only time you see them is when they’re onstage – I like to hang out with the people,” Buddy assures us. “I wouldn’t ever want to be so famous I can’t be seen at the grocery store or gas station. If someone recognises me, I don’t mind – I’m not going to turn my back.

“Sure, sometimes I get fed up with it, but it’s no different from any other working day. You just say to yourself, hey, I’m tired, so I’m going to go home, take a shower and come back tomorrow. But I don’t let the fans ever know that – I just use an excuse! I say that I’ve got to go to the bathroom or something, and take off. Next day, I’m ready for them again!”

Riding with the King

If we’re to believe what we read, 2006 might well be the last time that we see BB King tour the UK. It’s a sad prospect, and although the two bluesmen are from different generations, King’s retirement would inevitably leave Buddy – himself now 69 – as the senior bluesman on the block. It’s not a situation he regards with any enthusiasm.

“I read about it, but I don’t believe it,” Buddy says, shaking his head. “The way he loves to play, I don’t think he’s ever going to stop! I’m really not a young man any more, but BB can’t hand that baton over to anybody. If he does, I’m going to have to ask him just what we’re supposed to do if he hangs up?

“Man, he’s the father of bending strings and just about everything else that anyone who first picks up a guitar learns to do. They all have some BB King in their playing. There’s no one that can ever fill his shoes, or Muddy Waters’ shoes, or Howlin’ Wolf’s shoes; you have good and great people coming along, but when you were around those guys, your feet would be patting along just as they talked – and I’m not so good at it. When BB King started shaking his left hand, no guitar player had ever done that before. Now it’s something that we all do without thinking about it.”

Over the years, Buddy’s come in for more than his fair share of criticism about the pacing of his shows. New fans and reviewers alike are often baffled by Buddy’s enthusiasm for performing the music of his peers, such as John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters, rather than his own songs, but this quietly spoken man can at times be almost painfully modest about his own abilities: and when he performs songs like Hoochie Coochie Man or Boom Boom, it’s something he genuinely does with total reverence. Nevertheless, the criticism is obviously something that troubles him deeply.

“I played the Chicago Blues Festival last year for the first time in over 10 years, and at the end of my show, the whole crowd were screaming for more and they just wouldn’t let me leave the stage. Afterwards, one critic said that I was just a showman, but what can I do about that? I’ve been a showman all my life!

“When I read that stuff, I just have to tell myself that it’s the opinion of just one person… but sometimes, it does feel as though I’m in a kind of no-win situation. If I play the acoustic guitar, I have some people saying ‘Great!’, and then somebody else will be unhappy, saying they didn’t come here to hear me play the acoustic guitar. The public are so hard to please, but you just keep going, hoping that one day you’ll pick up your guitar and everybody’ll be happy!”

A deep well

It’s an unenviable situation, and it’s impossible not to sympathise with Buddy Guy’s position. The reality is that he has an astonishing back catalogue of material, and in recent years the man has recorded everything from an acoustic album to the laid-back, greasy, Fat Possum-inspired trance sounds of Sweet Tea. Still, it comes as something of a surprise to find that someone who’s just been inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, has been awarded countless Grammy awards and is acknowledged by the likes of Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck as the finest guitar player on the planet, suffers from stage fright.

“It’s true!” Buddy admits. “I suffer with it a lot, and in fact, it’s the only time that I drink, otherwise I’d think that I was an alcoholic! I drink a bit of Cognac and it calms me down – Muddy taught me that. Even when I’m playing at the club, I can hardly believe that all these people have come out in these temperatures; if they’re prepared to do that for me, then I just think I’ve got to go out and give them everything I’ve got. Still, I’m always nervous and worried about what people might think about the show.”

And if Buddy champions the cause of the blues with the kind of missionary zeal you would expect from a door-stepping evangelist, it’s hardly surprising. When it comes to his own albums – and with some justification – he’s often despaired of the lack of mainstream success he’s achieved. True, his ‘comeback’ album Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues generated some well-deserved attention in the Guy corner, but that was back in 1991.

“Better late than never,” Buddy wryly observes about his Hall Of Fame endorsement. “Blues is scary right now. You don’t really hear it on the TV any more, you don’t hear it on the radio. If you can’t sell records to kids between seven and 15 years old, you’re just not going to sell any records. I think sometimes that if my grandchildren don’t know who I am, there’s not much hope of anyone else knowing!”

Bringing his A-game

Now his new album Bring ’Em In comes on as a potent combination of blues and soul, with Buddy digging deep into his Southern roots. Recorded in New York and Memphis with veteran producer Willie Mitchell, best known for his work with Al Green, helping out with the horn arrangements, it’s his most fully-rounded album to date and also potentially his most commercial.

But, of course, Buddy Guy’s guitar is never far from the action, and on tracks like I’ve Got Dreams To Remember and Do Your Thing he comes up with the kind of deliciously sensual soul grooves you’d hear on a jukebox in any bar from Jackson to Beale Street come 11:30 at night – and if his sanctified reworking of Bob Dylan’s Lay Lady Lay with Robert Randolph on pedal-steel guitar doesn’t make you want to testify in church on Sunday, nothing will.

“I was very pleased with it,” Buddy agrees. “But you can still be sure that it’s not going to get any airplay. It’s quite a soul-influenced album, because I thought that maybe I could sneak in there and get a little more airplay with that kind of stuff; a college campus station might play a slow blues about three o’clock in the morning, but you’re not going to hear Buddy Guy otherwise!

“The problems go way back before the so-called British invasion of the States in the 60s,” he sighs. “Before then, everyone from Wilson Pickett and James Brown to Muddy Waters were classed as R&B players. Then they started separating it all out, putting blues into a separate compartment for people like myself and Muddy, and James Brown and Wilson Pickett became soul singers.

“When I first came up to Chicago, you just had to play whatever was on the jukebox – Ray Charles, Fats Domino. It didn’t matter what it was, and you’d slide the blues in there as well. You’d get a gig, because the club owners knew you could play what the people wanted to hear. They didn’t separate anything, either: it was just R&B. I’m not a baby anymore, and I don’t want to become an endangered species! I’ve been trying to do a commercial album since the 60s,” Buddy grins. “I’m starving, man, to keep the blues alive!”