How Devin Townsend dropped the comedy to create a genre-melding solo record

The boundary-defying prog-metal maestro on why he’s put comedy to one side and is feeling “truly alive” on new solo album, Empath.

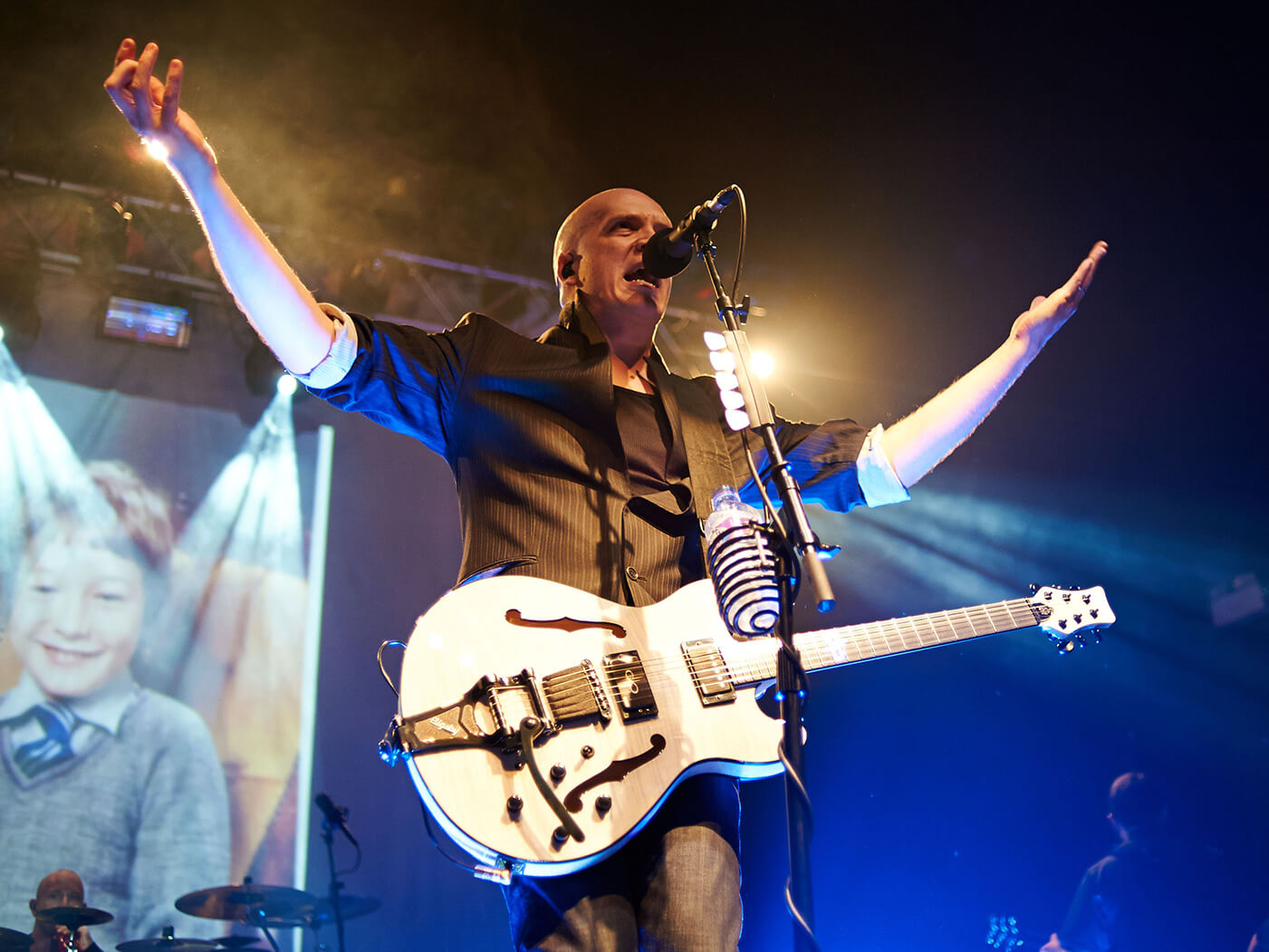

Image: Gary Wolstenholme / Redferns via Getty Images

Devin Townsend took everyone by surprise last year by announcing that he was putting his band, the Devin Townsend Project, on an indefinite hiatus. After seven studio albums and countless sold-out world tours, it seemed like the band were going on ice at the peak of their powers – so what went wrong?

The reality is that despite the success of the band Townsend was beginning to feel creatively stifled, and needed to spread his wings – a fact emphasised when he released a press release last year that he was working on not one, but four new albums, the first of which, Empath, has now arrived.

“I don’t know if it’s how it will be received that I’m apprehensive about; I think it’s the implications of making a record that is this vulnerable in a sense,” Townsend tells us, with uncharacteristic earnestness. Perhaps that’s fitting – Empath is an utterly uncompromising album, almost impossible to pin to a single genre, and light on the 46-year-old Canadian’s standard sardonic humour.

“For the first time, I’ve chosen to put all these styles in one place and done it without a comedic angle,” he continues. “It’s like a completely honest representation of where I’m at, at this point. I didn’t put a lot of strategy into making sure people perceived it in a very strategic way. That’s nerve-wracking for me, because I’ve got kids and family; it costs me so much money to make this record that I’m nervous because on a practical level, I’m like: ‘Oh my god, did I make a mistake here?’.”

Getting serious

That’s not to say that Devin has totally abandoned his comedic approach, but Empath is without doubt a challenging listen. In an age where people decide whether they consume a whole song based on its first 20 seconds, it must be acknowledged that perhaps this album could only have been made at this point in his career: after years of diligently cultivating a large fanbase who loyally follow Devin’s journey wherever it may take them.

“Yeah, I think that’s it’s not only that, but I’m actually welcoming of the fact that maybe some of the more recent fans that were drawn in by the more commercial stuff will just not be interested in this,” he admits.

“In a way, that makes it smaller than what it was, and I kind of like that in a weird way. There’s a sense that if I can just maintain the people who really understand why I’m doing what I’m doing, then I never really have to have any airs: I don’t have to have any masks whatsoever, I can just do what I do. This record is going to be polarising, and so far, there’s one of three reactions.

“There’s the first one where the person’s like, ‘I can’t get through it, it’s an impenetrable mess,’ then the other side where people are of the opinion that ‘this is the best thing that you’ve ever done; this is a combination of it all; you won’t repeat this ever’; then there’s the third that are just kind of like, ‘Yeah, just let me know when you write a chorus and I’ll come back’.”

It’s a searingly honest self-assessment, but this endearing frankness is a symptom of an inexhaustible, determined guitarist who feels compelled to follow his musical instincts wherever they take him.

“We can’t control where that muse leads us, and I think that it’s all cause and effect, so one life experience leads you to another and so on and so forth,” he affirms. “What I started recognising over the past couple of years is that I’m highly sensitive as a person, and as a musician. How that has manifested in my life is almost as a blockage of my emotional growth, where I feel so affected by people and media and things and music and all this, that I have built walls around myself emotionally that have allowed me to intellectualise my emotions without necessarily participating in them.

“Whatever the prior experiences that lead me to this place in my life were, I can’t quite recall, but it became clear to me that I really need to work on that. You really need to work on participating with those emotions, because at that point there��’s a real sense of vitality of it; there’s a real sense of truly being alive; there’s a real sense of not only having compassion for other people, but compassion for yourself based on willing to take steps to foster that sort of self-care. As a result of that, yes this record could only have happened now because that’s where I’m at.”

Devin’s advocate

Given the thoughtful introspection that was going on around the album then, it’s no surprise that Devin tended to work alone during the writing process for Empath, but there were a few co-conspirators, and none likely more important that Mike Keneally.

The guitarist has garnered a reputation over the years as a ‘musician’s musician’, drafted in by artists as diverse as Mastodon, Andy Partridge and Joe Satriani. Keneally is adept at serving up dissonant ideas in a very palatable way, and Empath is awash with dissonance and sonic chaos.

“One of the things I’m so thankful of Mike Keneally for is his ability to interpret my synesthesia in ways that other musicians can then follow, because I’ve had problems throughout my career of perceiving dissonance not as the notes, but as the emotions,” Devin explains.

“So, the creative process say in certain parts in Borderlands or Singularity or whatever, is less about this note fits with this note, or this rhythm counteracts that note in a percussive way, but more like this part needs to feel like a grey bunch of wires, and the wires are tangled up. In that one part of Borderlands, I would suggest that it’s not all grey wires – there’s a red one in there, there’s a yellow one in there.”

You can start to understand why Devin has struggled to communicate his ideas in the past, and it’s no doubt to the album’s benefit that Kenneally was hand to provide a conduit for these abstract concepts.

“That’s exactly what he does”, confirms Devin. “That really helped me. He wasn’t there for the whole process, he was there for maybe a month of the process and during that month, I had so much of it ready to be translated. It was really a great experience for me to not feel ridiculous when I’m translating these things, trying to explain these things to orchestras or choirs or what have you.

“A lot of times there’s a fair amount of elitism that comes along with musical theory, not being versed in that other than knowing what I want makes it very difficult to express myself. That’s basically my compositional formula: I just follow an internal visualisation like a literal picture and then try and make the music feel like what that picture looks like.”

Going alone

Given the fruitful collaborations on Empath, we wonder if Devin might consider working more collaboratively in future.

“Yeah, I think so. But I don’t want people to help me, I just want people in the room!” he laughs. “Even with Mike, at first we were trying to figure out a relationship; I thought that I wanted him to be like a traditional co-producer. But I’d be tracking guitars and he’d be like, ‘Maybe we can take that track again,’ and all of a sudden I was like, ‘I hate this, hate this!’

“So I was like: ‘I’m going to do the guitars on my own, because I just react really poorly to being told what to do, but how you’re going to help this for me is just be there. Check your mail, drink some wine – having you there, I can sense much more about my music.’

“So when Mike left there’s a bunch of other musicians that I knew that I called them up and said, ‘Hey… you’ve got a studio, I would like to come and see you,’ they were like, ‘I thought you had a studio?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, I just want somebody there!’.”

The album’s longest, and perhaps most challenging track is Singularity – a 20-minute-plus six-part epic that closes out Empath. Such a broad composition might seem like it’s open to interpretation, but Devin is surprisingly adamant that the song’s original meaning be the one that people take from it.

“I’m hesitant to have people interpret it in ways other than how I mean it, actually,” he insists. “I think you can draw conclusions from it that are not what I meant to say: my intention from the beginning of this record was to do something that helps people. I know a lot of people who suffer from depression; I know a lot of people who are suicidal or have killed themselves or attempted to kill themselves, and that’s a very big problem.

“Myself, I’ve gone through depressive moments as well, and the world is in such a place right now that often I’m sure most of us have this sort of sense it’s like, ‘God, how do we even continue?’ So the idea of Singularity was supposed to be a character, a protagonist, who’s lost in the beginning, and the island that he finds himself on is a metaphor for his mind.

“In order for him to not allow the monsters that inhabit this island to take him over and force him to surrender to that self-deprecation, and the fear, and all that often is part-and-parcel of depression. He has to basically go through it. Each section of this is increasingly more of the journey.

“In the beginning, he’s on the island, then all of a sudden he’s preparing to go through this journey. Then there’s a sense of strength, then there’s a sense of peace, but then after the peace, there’s this sense that now that we’ve recognised that this is something we have to go through, we also have to recognise that with the good comes the bad.”

Attitudes towards mental health have changed significantly in recent years, but there’s still definitely a stigma associated with it, something that worried Devin when he was being so open about such things…

“I think that there is,” he agrees. “And I think that maybe this is what my fear was with this record is that being vulnerable about the fact that – man, I get depressed too, and I’ve gone through a lot of situations with mental illness – you’re going to be viewed as being weak, ultimately.

“I think one of the liberations of this type of surrendering to what you can’t control comes with the fact that I’m clearly not alone. I’m clearly one of many people, millions and millions of people, that have these thoughts and these moments. So to make something artistically relevant to me out of that fight hopefully will maybe inspire other people to do similar things.

“I’ve got kids, too: I hate thinking that kids get to the point where they feel like, ‘I’m not worthy of being loved; I’m not worthy of any of these things.’ If what it’s going to take to make it visible is for artists like myself and many other artists who are broaching the subject now, to put yourself in a position where you feel vulnerable, then that’s not a huge cost in the long run.”

Empath by Devin Townsend is out now on InsideOut.