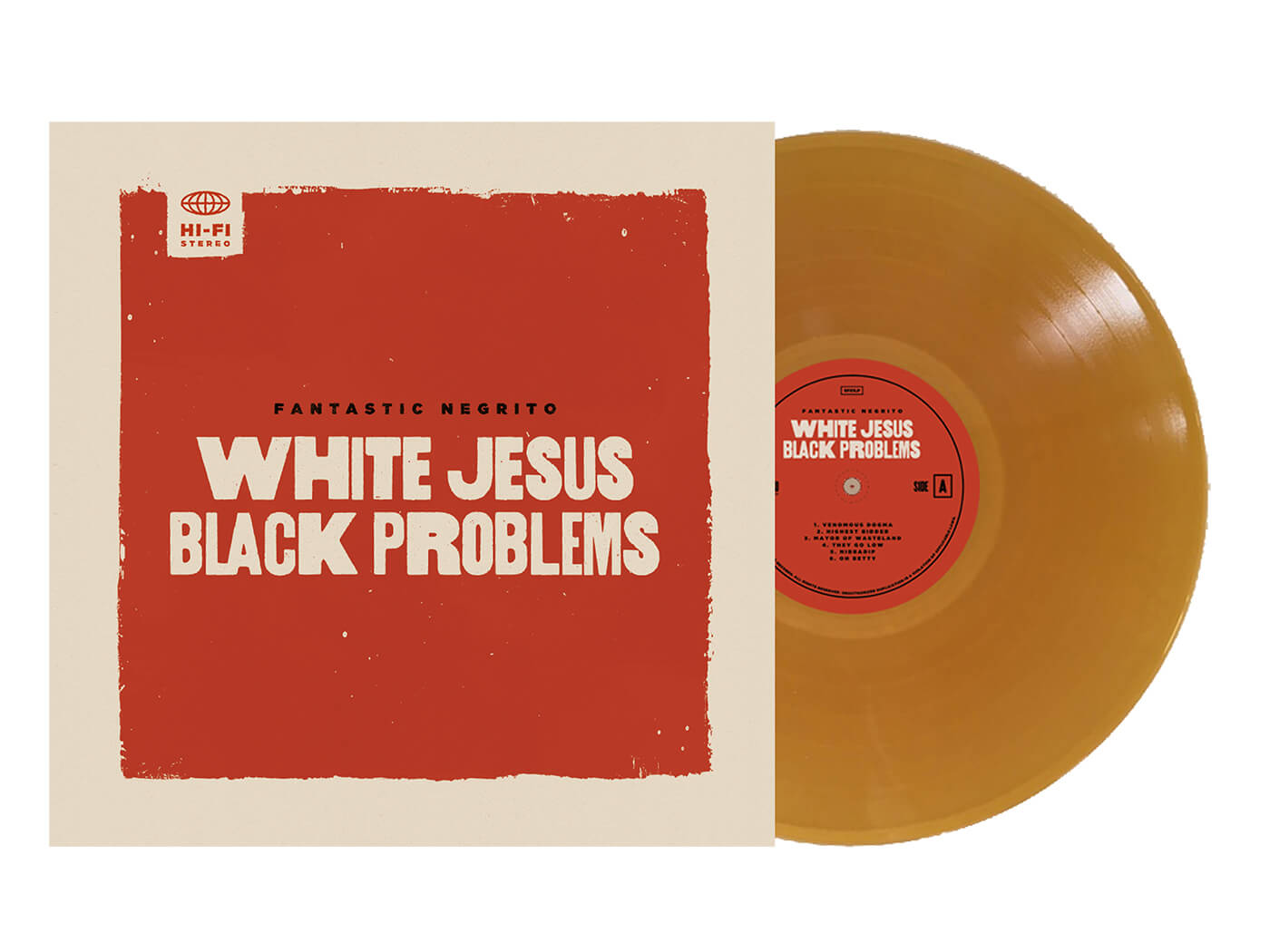

“It was like a speeding train and I just got on it”: Fantastic Negrito on how his 17th-century ancestors inspired his eclectic new gospel-psych-blues jam album

The Grammy-winning RnB, soul, jazz, psych-rock bluesman trips through time and genre to deliver a paean to the doomed love affair of his seventh-generation grandparents.

Image: Press

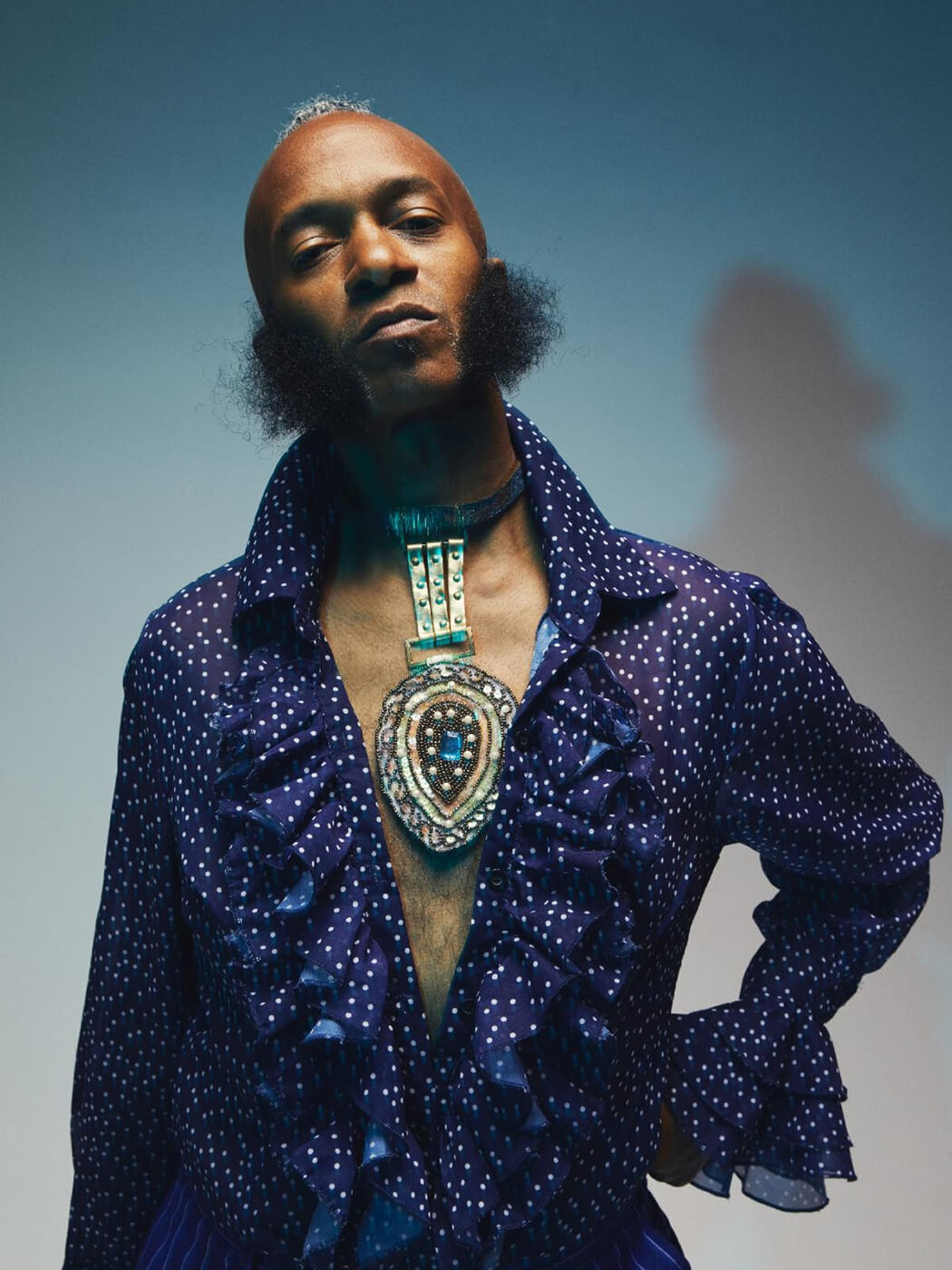

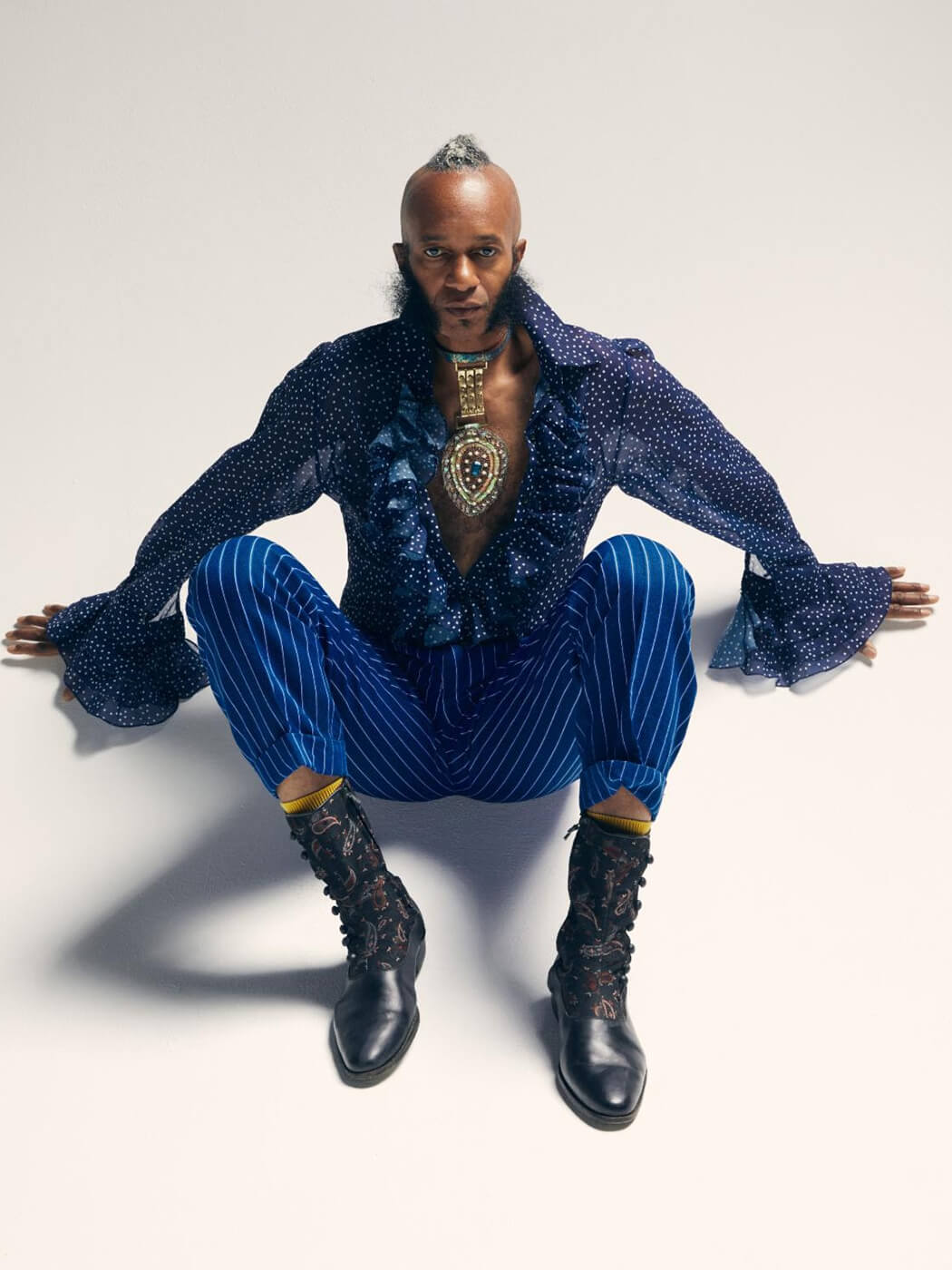

Six albums – five as Fantastic Negrito, his moniker since 2015 – more than four record labels, three Grammys, 54 years, and one coma. If you could tally up a life in numbers alone, Oakland-based Fantastic Negrito, born Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, has already notched up enough experiences to warrant a memoir. Who knows when the Massachusetts-born artist would find the time to write it, though?

When he joins Guitar.com on a late Melbourne evening, it’s noon in Utrecht, central Netherlands, where Negrito is mid-tour.

“I’ve been on tour for the past few weeks,” he says. “It’s a different feeling, doing gigs post-pandemic.”

It’s a world apart from the Oakland farm, replete with chickens and pesky foxes, where Dphrepaulezz lives with his 13-year-old son, and his dog. It was there that he had the time and imaginative capacity to study his family history and turn a major discovery, a revelation even, into the concept of his fifth album, White Jesus Black Problems.

It sounds like an epic undertaking, and the album is comprehensive in its gospel, funk, blues, rock and soul jams. For those unfamiliar with the eclectic “marketing nightmare” that is Fantastic Negrito, that might come as a surprise. Right?

“I don’t think I’m ever surprised at what I do,” he responds. “This one was easy, because it really wasn’t my story. This is from 263 years ago, it was a debt that my seventh-generation grandparents had paid and I felt like it was my responsibility to tell the story and to stay out of the way of something that was riveting, powerful and compelling. It felt like a Romeo and Juliet story in a way.”

As humble as he is, Dphrepaulezz has not stayed out of the way so much as worked relentlessly and passionately since picking up a guitar again following a traumatic experience and determinedly teaching himself how to play anew.

Indeed, he has been working ever since signing a record deal with his hero Prince’s former manager, Joe Ruffalo, more than 30 years ago. Except, of course, during the coma.

In 1999, a near-fatal car accident left Dphrepaulezz comatose for almost a month. It was not the first traumatic experience for the veteran RnB-roots-soul artist, but the deadliest. It woke him up, he later admitted, and reset his path. He committed to it through the handclap-spattered, hollerin’ gospel blues of his 2014 song Night Has Turned To Day, on which he sings, ”But when I swam deep in the river / Of my conscience I defined / Self-reflection, new direction / To a healthy state of mind”.

To understand his workhorse, hustle-and-flow mentality, we must return to his roots: Dphrepaulezz was a defiant youth who, as the eighth of 14 children, ended up in the foster system after leaving home at the age of 12. What his Somalian-born father might have shared about their family history was not to be imparted. Young Dphrepaulezz didn’t see his father again after leaving, but learnt of his death two years later.

Hunting through his history to make sense of his identity as a Black man, a father, a songwriter and performer in a Trump and post-Trump world, required time and resolve. Luckily for us, Fantastic Negrito recreates this ancestral deep-dive gloriously on White Jesus Black Problem, which trawls his ancestry to pinpoint the period where a white Scottish woman had relations with an African-American slave, and defied the oppressively racist, separatist 1750s colonial Virginia.

Grandma Virginia Elizabeth Gallamore, Dphrepaulezz’s seventh-generation white Scottish grandmother, and Grandfather Courage, his enslaved seventh-generation grandfather (whose name has been lost to history), are the real characters who have inspired both this new album and its accompanying film, both released through Dphrepaulezz’s own Storefront Records.

“I just accidentally stumbled upon this information during the pandemic and, as an artist, I think inspiration is everything,” he says. “I felt very inspired, during the pandemic, to do something, and it was right there. It wasn’t a lot of work, it was just something where it was like a speeding train and I just got on it, got outta the way. It was pretty amazing! I felt like every song was a chapter in the book of this quite shocking story: a white, Scottish, indentured servant freely decides to have a child with a Black enslaved man.”

On Highest Bidder, over a burst of sunny 1970s jazz-funk and juicy bass, he delivers his stories in a haunting bluesy howl, soulful croon and throaty falsetto. Elsewhere, Sweet Betty offers Hendrix-style wailing rock guitar and tenderly plucked bass atop a wild Frank Zappa-esque keyboard melody. It’s Motown meets psyched-out jam rock. Redolent of a heavy metal ballad, They Go Low features a piano-gospel harmony delivered over a thudding, doom-laden bass drum. The 13 tracks are eclectic but, as a cohesive body of work, this is 100 per cent Fantastic Negrito.

“Sonically, it was just an animal that was doing its own thing, and I just thought, ‘Wow, this is happening, okay, we’re doing this, great. Let it happen, let it be completely organic.’”

The first song on the album, Venomous Dogma, was also the first he wrote. “Venomous Dogma was quite twisted and interesting,” he begins, laughing in his deep, almost drawled gravelly baritone, musical and compelling even over Zoom. “It’s a little bit unusual to what I’d usually do, and I’m always encouraged by that, to do something different. Venomous Dogma was in two parts, and I thought of contrast: America during slavery, an indentured servant in Scotland; Africa, Virginia, so much contrast. It was just doing its own thing, it was amazing how it was coming out. I think maybe the engineers and people around me were maybe surprised by what was coming out – like, ‘What is this?!’ – but for me, it’s a compliment. I’m a marketing nightmare to people who wanna make money.”

That’s debatable, since Negrito is evidently winning over the industry, international audiences, and the music media. Still, if you like your music and musicians to be safe and vanilla-flavoured, Dphrepaulezz will not play along.

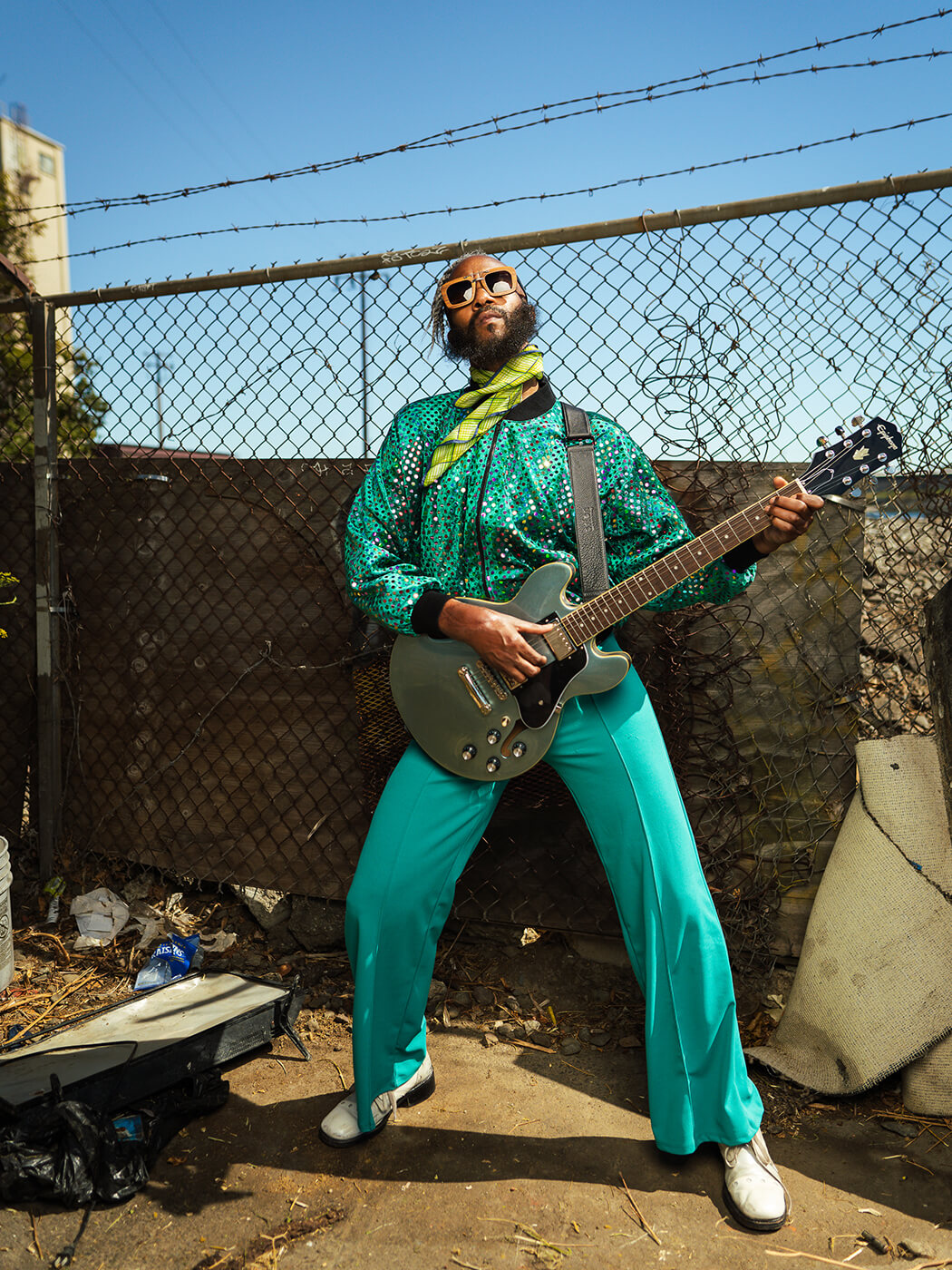

But boy can he play. Across White Jesus Black Problems, Negrito wields a vintage Gibson Les Paul Hollow Goldtop made for only a few years in the early 1970s, plus a Chapman ML3 Pro, a Gibson Hummingbird, and a 1960s Harmony Acoustic Monterey, a model favoured by Elvis Presley and Scotty Moore. But that’s not all.

“I played bass a lot on this,” he says, “and all the rhythm guitars, [because] they were a little bit awkward for the usual guitar player… I was playing, then we’d go back and forth [between recording and mixing], and to my surprise we kept a lot of my strange guitar parts. The album kept a lot of my bass parts too. It’s just an album like that, where it was all over the place and quite quirky. I’ve always liked the intention behind the notes, music, and chords. The intention is more important than the performance.”

In getting out of his own way, or riding that speeding train, Dphrepaulezz was able to create some unusual and fantastic guitar parts on White Jesus Black Problems, plus – listen closely – is that a banjo?

“Man With No Name has some quirky parts, and also on Virginia Soil. Those two stuck out, and I even incorporated some banjo on that one, though I don’t think anyone can tell. I was just taking banjo parts and mixing them with guitar. It made for a very interesting language of strings. Even on Highest Bidder there’s a little banjo played in a very interesting fashion, and the rhythm guitar was very specific on that.”

How specific? Negrito clarifies: “It was specific in the feel of the rhythm, there was an off-ness to it, rhythmically. It’s something in between Afrobeat and funk, just very specific. My playing tends to be very percussive because of the limitation in my right hand, and without a pick always, everything without a pick.”

That limitation, of course, relates back to the accident. It left Dphrepaulezz unable to play guitar, just one of the many things he had to re-learn and feel courageous enough to start over with.

“I had to learn to do it all again to be honest,” he says. “I just didn’t play guitar for years. I really just avoided the guitar because it seemed pointless and depressing. I didn’t play for seven or eight years. I gave up on it. It seemed impossible, so I started a punk band and ruined my voice for a while, just screamed, and got into the Afropunk scene, which was big then, in the early 2000s. One day, at the beginning of the Negrito period, I just thought, ‘Whatever I have, I’m just going to work with it’. I think I started accepting myself as a person more.”

Having made such a sombre reflection, he lightens the tone, adding mischievously: “Then I felt the courage to be a horrible guitar player.”

This fifth album, which follows three consecutive Grammy-winning records, proves his idiosyncratic hand for guitar, bass and banjo is spellbinding. Taking a handful of funk, a pocketful of blues, a nip of metal, a pinch of jazz and a whole lotta soul, it’s pure Negrito. Three Grammys for Best Contemporary Blues Album provides the sort of tangible, take-that-and-bank-it validation that gives an artist the stamina and assurance to seek new ground, and know there’s an audience adventurous and committed enough to follow. But the awards – for 2016’s The Last Days of Oakland, 2018’s Please Don’t Be Dead, and 2020’s Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? – are not his north star.

“I don’t pay attention to that stuff,” he says. “I live on a farm and Oakland’s a small city. I’m free from all that judgement. The music business destroys people. It’s like a vampire that sucks the life out of people then looks for new victims. It’s nice when it happens, you call friends and be grateful. At the same time, I don’t want that in my head. I don’t want to be told, ‘Make albums and songs like this, trying to go for this and be that’.”

The 54-year-old, eminently fit and fashionable to an almost criminal degree, isn’t interested in playing it safe. His propensity for rebels draws him to artists of a similar bent: Fela Kuti (“all day”), The Beatles, Kendrick Lamar.

“I don’t wanna keep doing the same thing,” he adds. “You do lose people sometimes, but somebody’s gotta do it. Somebody’s gotta not care about these boundaries that are set up for us, you know? I love freely writing, composing and producing… I never liked safe artists, I never wanted to be one.”

White Jesus Black Problems is out now on Storefront Records.