“You start to see how you can make the guitar sound so much bigger”: Fontaines DC on taking things to the next level on A Hero’s Death

It’s been a dizzying three years for Fontaines DC, who released their second album A Hero’s Death at the end of July. The Irish band tell us about their love of 60s Fenders, selling out Brixton Academy and how they want to write a “weird as fuck” new album full of bangers.

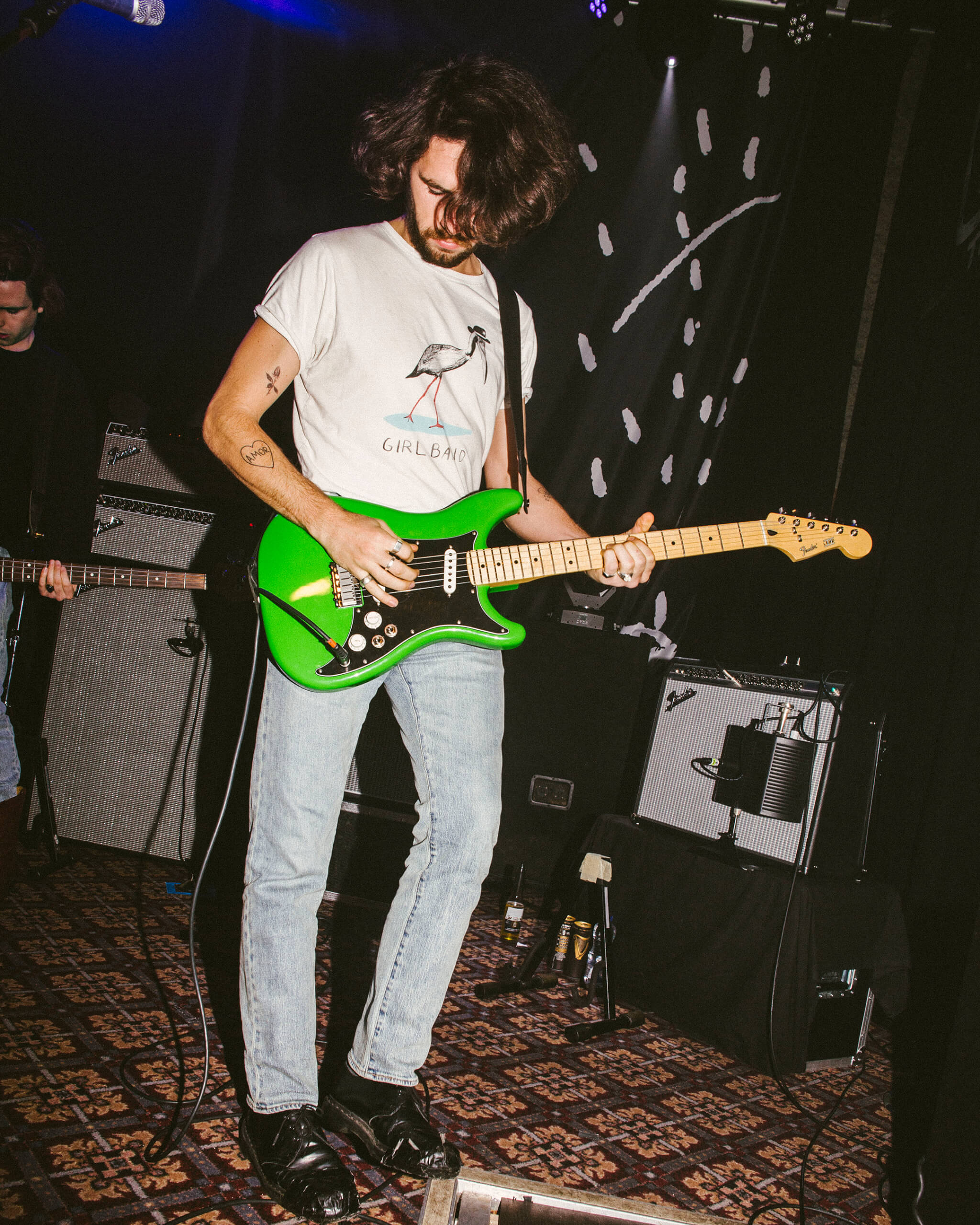

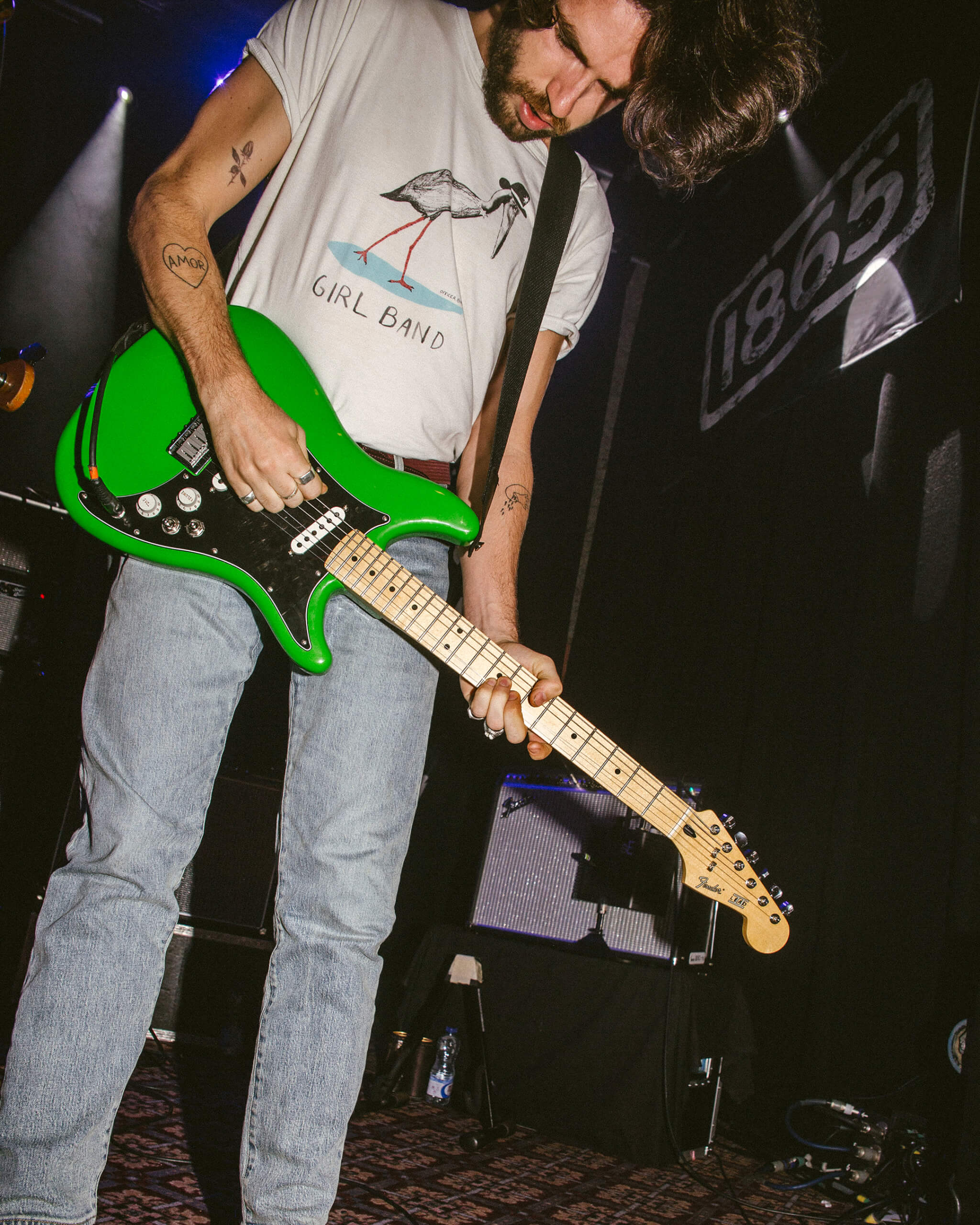

Image: Ellius Grace

“We didn’t know what we were wishing for when we were moaning all of last year. I’d love to go back and torture myself again on the road.”

The irony of their current predicament is not lost on Fontaines DC guitarist Carlos O’Connell. Barely seven months ago, the band were desperate for a break from touring. Now he’s spent weeks following the release of the band’s outstanding second album, A Hero’s Death, at the end of a lockdown summer climbing the walls of his home in Ireland. Some 3,000 miles west in New York, fellow guitarist Conor Curley has been similarly restless.

Sandwiching the release of their adrenal debut album Dogrel in April 2019, Fontaines DC had been on the road since the autumn of 2017. The gig itinerary ran into the hundreds, the size of the venues escalating with each lap. They’d toured with Idles, played four times in a weekend at Glastonbury and nine times in five days at SXSW Festival. The end of the road was a sold-out Brixton Academy this February.

The dizzying whirl of touring was swallowing the band whole. Pints of whiskey were sunk before shows, food and sleep became fleeting strangers, relationships were disintegrating. As frontman Grian Chatten put it, “Our souls were kicking back against walls that were closing in.”

The settling grey horizon of the Irish Sea called, remaining dates were cancelled and the quintet retreated to Dublin, taking comfort in what they know best – writing. What emerged was an even better album than their debut, brooding, defiant and immersive, O’Connell and Curley conjuring caliginous surf soundscapes for Chatten’s scabrous baritone to unfurl across. How they’d love to get back in a van and tour it.

“I hadn’t listened to Dogrel in over a year and I was like, ‘Fuck, this is good’”

We join both guitarists on a transatlantic Zoom call, a well-loved archtop leaning against the bare-brick wall of the New York apartment Curley has shared with his partner since lockdown began. O’Connell has spent the morning listening to Dogrel and A Hero’s Death. When asked how he feels about the latter given the luxury of perspective, he answers: “Proud. I love it. I hadn’t listened to Dogrel in over a year and I was like, ‘Fuck, this is good’. When I listened to A Hero’s Death, I was like, ‘This is really good’. I love it, I never got sick of listening to A Hero’s Death making it.”

Dirty old town

Dogrel was a stirring portrait of 21st Century Ireland, where all five members of Fontaines DC grew up. O’Connell was born in Madrid, Curley in County Monaghan, bassist Conor Deegan and drummer Tom Coll in County Mayo and Chatten in Barrow-In-Furness. Both guitarists remember vividly the moment their six-string adventures began.

“I got a classical guitar when I was 10, and it didn’t do much for me,” says O’Connell, “but a couple of years later I got a cheap fake Strat, and that was pretty cool. My first guitar I loved was an Epiphone Les Paul 100. I used to go down to the guitar shop and stare at it in the window with my forehead pressed against the glass.”

“My first guitar I loved was an Epiphone Les Paul 100. I used to go down to the guitar shop and stare at it in the window with my forehead pressed against the glass”

Curley’s awakening came at a school talent show, aged nine. “I was sitting there bored, and suddenly there was this absolute fucking explosion of noise, a load of lads came out in dresses and started kicking the shit out of their instruments and one guy skateboarded across the stage. The only time I’d thought about music before that was listening to Dirty Old Town and John Denver with my dad in the car. It was the moment music hit me across the face.

“After that, I became a little punk. I went to the guitar shop and told the guy I listened to the Ramones, Sex Pistols and all these punk bands I hadn’t really listened to. He gave me a Cort 200. I tried to do that thing where you flip the guitar over your shoulder, but it fell on the ground a couple of times, it was banjaxed… Once I started playing in bands, though, everything seemed to accelerate.”

That pace has never abated. The band met at Dublin’s British & Irish Modern Music Institute, drawn together by their shared love of poetry. Bonding over Rimbaud, Joyce, Yeats, Ginsberg and Seamus Heaney, they knew “from the start” that Fontaines DC, the name taken from The Godfather’s Johnny Fontaine, were going to conquer the world.

“We went out one night and were musing over the idea of starting a band that had the depth of songwriting of The Beatles, but the ferociousness of The Clash or the Sex Pistols, an idea that’s so common,” says Curley, laughing at their youthful precociousness, “But after way too many drinks we were like, ‘no-one’s ever thought of this before’.”

While Fontaines’ songs are driven by a relentless poetic meter, their thrumming two-guitar attack was influenced by a pair of records that defined guitar music in the early 2000s – The Libertines’ Up The Bracket and Is This It by The Strokes. There’s a nod to the latter in the rhythm guitar of A Hero’s Death’s thrilling title track, a life-affirming missive centred around the hopeful mantra that “Life ain’t always empty”.

“The Strokes are absolutely mechanical and The Libertines not at all, but somewhere in the middle was something beautiful”

“Those two records were a massive influence at the start,” says O’Connell. “Then we started finding our own sound. They were a good gateway. Early on in the band, there were a lot of downstrokes, sort of ‘ching-ching-ching’, rock ’n’ roll in a modern setting – that was a direct Strokes influence, and The Libertines had the rough-around-the-edges thing that attracted us even more. Those two bands are so different in the way they approach guitar: The Strokes are absolutely mechanical and The Libertines not at all, but somewhere in the middle was something beautiful.”

Rejecting paradigms

Fontaines DC quickly began shaping their own dynamic, one that would earn Dogrel a place in the UK Top 10 and a Mercury Prize nomination, the guitarists rejecting traditional rhythm and lead paradigms. “I don’t see most of our songs as having lead and rhythm parts,” says O’Connell.

“The idea is a little bit restrictive,” adds Curley, “because you’re always trying to adhere to it – that was the chorus, the lead player should probably play a lead line now…”

With its evocative poeticism (“The city in its final dress, And now a gusty shower wraps the grimy scraps”) and wide-eyed proclamations (“My childhood was small, But I’m gonna be big”), Dogrel was an audacious opening salvo. Here was a band with the chest-beating bluster of Oasis, fearsome discord of The Fall and scruffy romanticism of Arctic Monkeys, yet they could give The Smiths a poetry lesson. Their ascent bordered on the vertiginous. On 23 May 2018, Fontaines DC played to 96 people at London’s Shacklewell Arms. On 20 February this year, they sold out the 5,000-capacity Brixton Academy. The vast Alexandra Palace was booked before Covid intervened.

“It’s surreal to me now,” says O’Connell. “At that time, it felt like a natural progression, but it’s been such a short time looking back, now we’ve managed to stop for a bit. It blows my mind how much we’ve done in a couple of years. Before that, we were nothing. We’d tried so hard to get signed and no-one wanted anything to do with us. It’s mental, I don’t know how it happened.”

“It blows my mind how much we’ve done in a couple of years. Before that, we were nothing”

Locked in the jaws of that seemingly endless tour, the band grasped every spare second to write their sophomore album. “We were motivated by the fact we were getting sick of playing the same songs,” says O’Connell. “We’d been playing Dogrel songs for two, maybe three years and it was adding to how run down we were feeling.”

Upon the release of A Hero’s Death, which takes its name from a line in Brendan Behan’s 1958 play The Hostage, there was a sense of the band rejecting the expectations hoisted onto their shoulders. The album’s title playfully suggested a desire to pull down their own edifice and Chatten said he wanted to shock the band’s audience. “If people don’t like it, their band is gone,” he declared unflinchingly. On its seething opening track, the clanging gothic riff referencing The Stooges and Interpol, he asserts, “I don’t belong to anyone”.

“It was a way of re-appropriating our own music,” explains O’Connell. “That change from being a band no-one knows to one people do know is quite weird. Something that was your secret, when everyone knows about it, you take it for granted a bit, and we needed to claim it back and start writing from our own perspective outside the public gaze.

“When we wrote the first record, it was the music we wanted to hear. The fact someone is listening and expects something shouldn’t change that, because that’s when it becomes boring. Even though people might think they want the same thing they’ve listened to already, they don’t. No-one wants that.”

Getting bigger

That vehement determination to keep innovating manifested itself in an evolution of the band’s guitar sound. It’s no slight against the angular assault of Dogrel to say A Hero’s Death is sonically in a different league, a mesmeric soundscaping soup that sees the gloomy noir of Joy Division and The Birthday Party collide with Beach Boys harmonies and lacerating surf guitar. A Lucid Dream is a simmering wash of interlocking lead lines, Living In America bristling savagery, while Such A Spring’s simple arpeggios chime gently beneath the album’s most mournful lyricism. Down by the docks, surrounded by sailors drinking American wine, Chatten’s fatalism is somehow beautiful: “The clouds cleared up, the sun hit the sky, I watched all the folks go to work just to die.”

“One of the themes on the album is this lower-register single-note cowboy-style playing – we drew influence from [The Birthday Party guitarist] Roland S Howard”

“We started to explore the soundscapey stuff towards the end of the first record,” says O’Connell. “We’d done the chordy thing enough and we picked up from this new door that we’d just pushed open slightly. We were more interested in sounds and atmospheres. At the start, we didn’t have pedals, maybe an overdrive and a reverb. You start to see how you can make the sound of the guitar so much bigger.”

“One of the themes on the album is this lower-register single-note cowboy-style playing – we drew influence from [The Birthday Party guitarist] Roland S Howard,” adds Curley. “The first album was very abrasive, things clashing together, the chords hitting off each other. It’s very effective for that kind of music, but the two guitarists are not really having a conversation.”

Naturally, a more expansive sound meant more pedals. O’Connell’s drive sounds came from an Electro-Harmonix Soul Food and JHS Double Barrel, with a new weapon slicing its way through swaggering lead single Televised Mind: the Cosmic Tremor-lo, based on the vintage Vox Repeat Percussion.

“I got really into tremolos and how you can use them rhythmically, setting them off the drums to create a polyrhythm,” O’Connell says with relish. “It’s made by this guy [Cian Megannety] from Dublin, Moose Electronics. He makes the reverb we both use, too. I got really into Spacemen 3, their percussive tremolo thing. We were at Moose’s picking something up, and he had this Spacemen 3 pedal.… I was like, ‘I want it’.”

“I used primarily a Strymon Deco for the tape saturation,” says Curley. “Lots of distortions have their own voice and I didn’t want that, I wanted the amp to just sound like it’s turned up, then I have a JHS [Morning Glory] for the dirtier stuff.”

Sticking to what works

After sessions in LA with Idles and Nick Cave producer Nick Launay, the band returned to Dan Carey, who’d helmed Dogrel. “Dan just understands the world we’re trying to create,” says Curley. “He does nothing but enhance the way we sound.” Carey’s 1975 Deluxe Reverb was A Hero’s Death’s go-to amp, with Curley and O’Connell using exclusively Fender guitars. Both guitarists were featured prominently in the campaign for Fender’s reissue of the Lead II last year, but Curley’s number one instrument remains a 1966 Fender Coronado, bought from SomeNeck Guitars in Dublin, although he’s also been seduced by the versatility of a Johnny Marr Jaguar.

“That’s pretty much all I use live,” he says. “There are songs I use the Coronado’s hollowbody, garagey, psychy sound for, like Televised Mind, but anything else, the Johnny Marr Jag can do. It’s such an amazing piece of equipment. Jaguars are usually limited in what they can do, but this one… any song on Dogrel or the second album I can dial in on that guitar.”

“There are songs I use the Coronado’s hollowbody, garagey, psychy sound for, like Televised Mind, but anything else, the Johnny Marr Jag can do”

O’Connell, who played a Danelectro 56 Pro in the band’s early days, is now a Mustang man, reaching for his 1966 example to demonstrate why it’s so integral to A Hero’s Death. “I used two Mustangs – mine and Dan’s. His is from ’65 and mine’s from ’66. I also used an old Jazzmaster for the darker songs, a 60s reissue prototype that I got my hands on. It’s got P-90s and you can get this low, hazy sound with no brightness at all.

“I love the Mustang’s bridge. I love how easily you can play a chord and then use your hand to bend the notes [he demonstrates]. You can be playing a constant thing with the low end and bend the high strings downwards, like on A Lucid Dream. There’s a lot more control than with a whammy bar. I couldn’t really play the new record without a Mustang. Since I’ve had one, I’ve learnt to approach the guitar differently.

“I’ve got so much better at guitar since that first record, I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. Playing the songs from that record live so much, I’ve figured out ways of doing them better. With A Hero’s Death, we haven’t had the chance to tour it…” He tails off, frustrated by the enforced inactivity.

Unable to tour the record they made in order to escape the insanity of touring, what’s left for Fontaines DC to do? Looking a little glum and increasingly twitchy as our call nears its end, O’Connell has the solution. “I’d love to put out another record next year,” he declares, the brightness returning to his eyes. “If we get time to be together and write, I’d love to do it. It’s the only thing we can do right now, so we should do it. I want the next album to be full of bangers.”

So, if the first record was the sound of Dublin in transition, “A pregnant city with a catholic mind”, and the second was a determined refusal to bow to public expectation, how might the third Fontaines DC album sound? “It definitely could have a bit more of a romantic descent into madness sound, I think,” says Curley. “We’re getting more comfortable with dealing with more manic sounds and trying to orchestrate that over beautiful songwriting. I’d love it to be as weird as fuck, and maybe a little bit harder to digest, just to see what we come up with.”

A third Fontaines D.C. album in as many years, that’s uncompromising, challenging and yet better than anything they’ve done before? You wouldn’t bet against it.

A Hero’s Death is out now on Partisan Records.