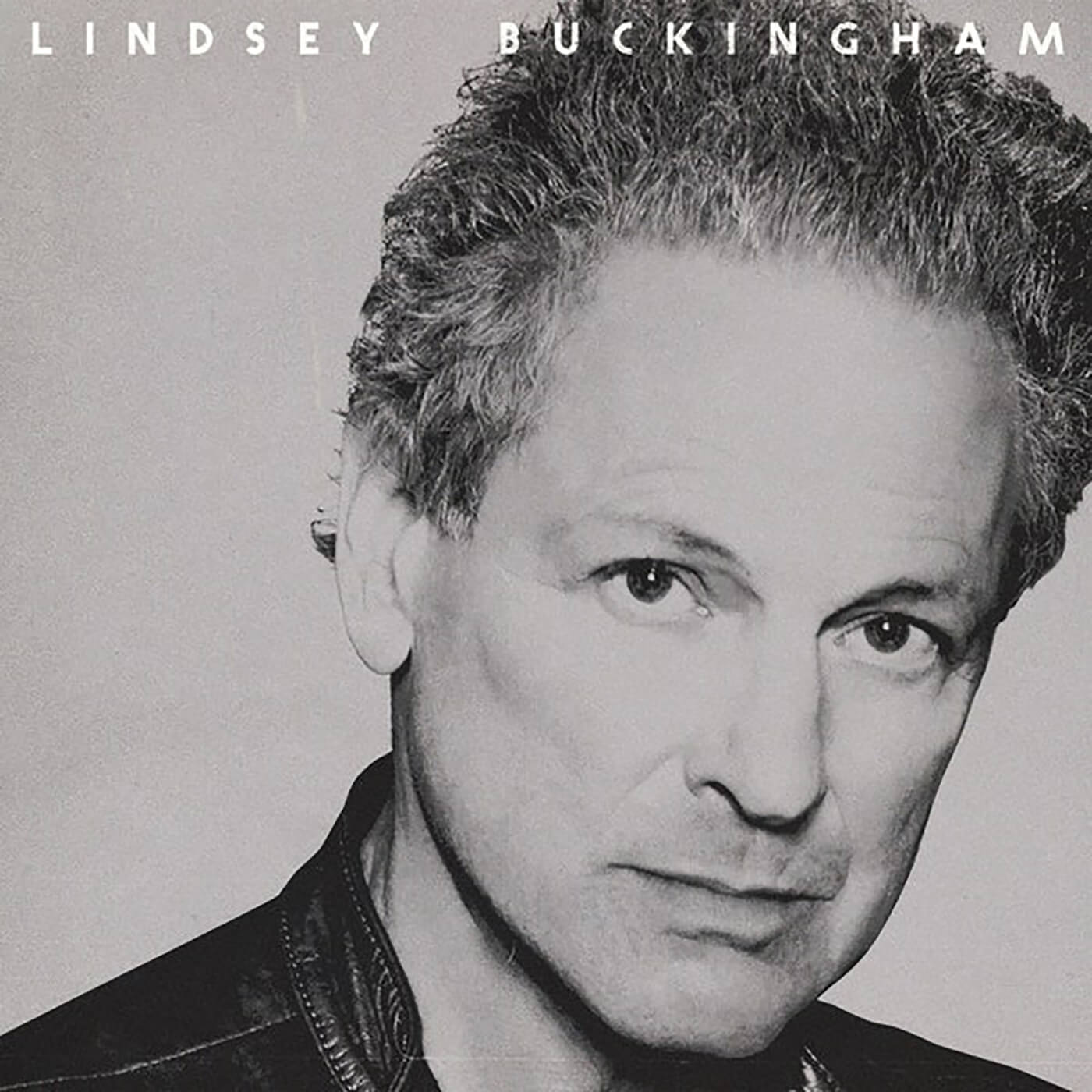

“I love that Peter Green stuff, but it wasn’t me”: Lindsey Buckingham on Fleetwood Mac and his first album in a decade

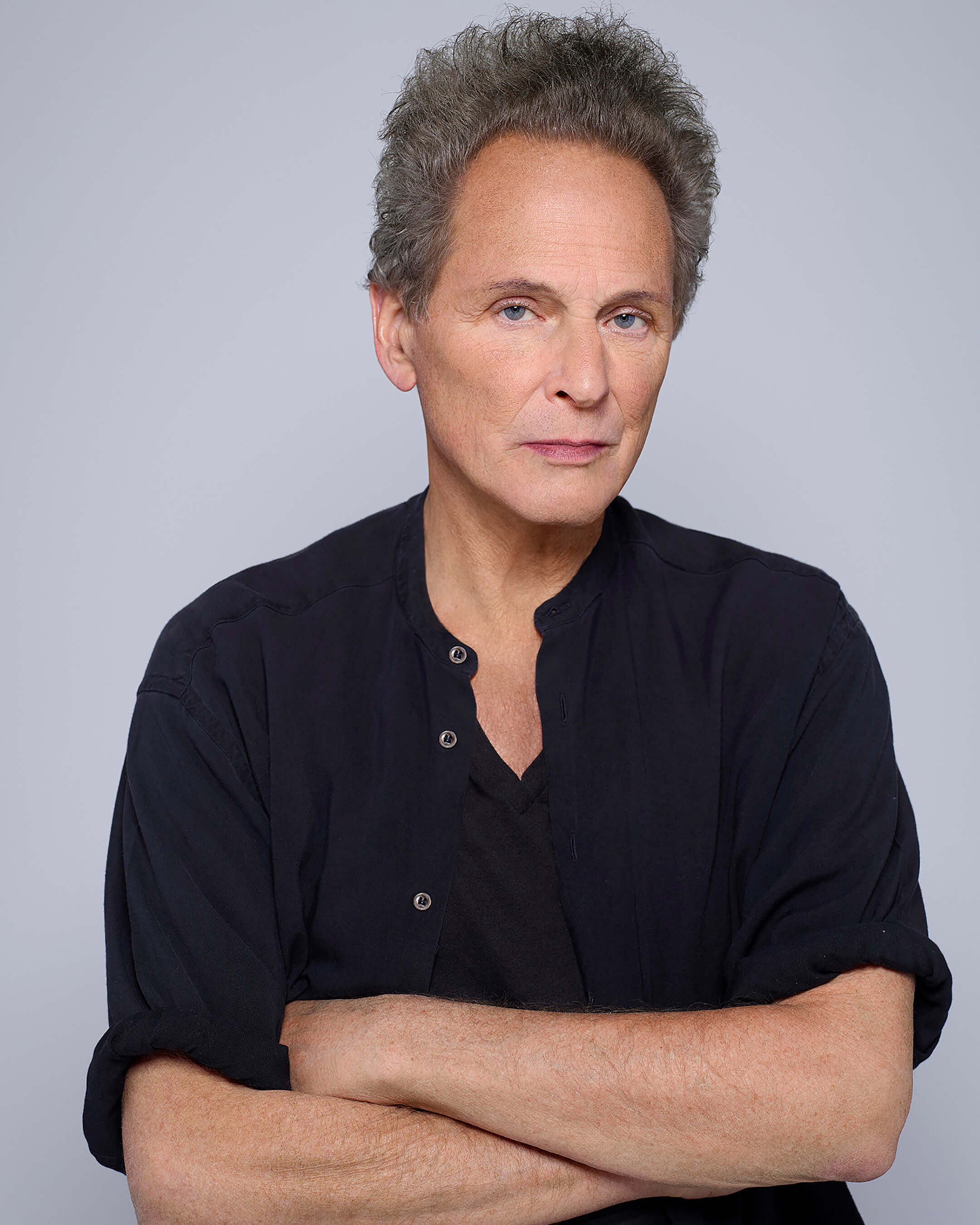

The former Fleetwood Mac guitarist on how he’s always been his own man, his love of Strats, and why he’s not seen his ’59 Les Paul in years.

Somewhere in Los Angeles, there’s a warehouse – probably climate-controlled, certainly high-security – that houses some of Lindsey Buckingham’s rarer guitars. There’s little point asking Buckingham himself what’s in there, though.

“Oh, good question,” he says, on the phone from his home in California. “I don’t know. I don’t have a collection for the sake of a collection – it’s just something that I ended up with for some reason. I think probably the most valuable guitar I have there is a ’59 Les Paul. I haven’t even seen it for years, but I know it’s there!”

It turns out that Buckingham’s stash also includes a rare Alembic 12-string, a 60s Gibson J-200 and an Epiphone Airscreamer, built to resemble an Airstream trailer, according to his long-time tech Stanley Lamendola. Yet the guitarist’s ambivalence to these in-storage treasures isn’t the jaded response of a man who can afford anything – rather, Buckingham’s always been a guitarist happy with a sparse set of tools, who makes magic with technique more than gear.

“It’s not what you got, it’s what you do with what you got,” he explains. “I guess I’m getting all this stuff done in my own way. It’s about limitations? Well, that’s what I try to tell myself!”

In a similar fashion, Buckingham’s new self-titled solo album, his first for a decade, was recorded in his modest home studio on a Sony 48-track tape recorder. Close to hand were his trusty ’62 Fender Stratocaster, DI’d straight into the reel-to-reel, and a Martin D-18.

Though he has the chops, Buckingham is much more interested in serving the song than showing off. “You do hear some players who just tend to play on top of a song and not inside it,” he says. “Then there are people like Chet Atkins, people who play parts that make the records what they are, but sometimes you don’t even notice the parts. That’s what I would gravitate to, you know, over just ‘Listen to me play…’”

Record player

Lindsey Buckingham has always been more fascinated by songs and records than by guitar style. Growing up in the Bay Area, he was blown away by the first flush of rock’n’roll, courtesy of his older brother Jeff’s expanding record collection.

“Without him, I probably wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing,” says Buckingham. “I was only six when Elvis Presley came on the scene with Heartbreak Hotel. It’s hard to even characterise how impactful that was. At six years old, I wasn’t in any position to be buying hundreds of 45s, but my brother, who was seven years older, came home one day and said, ‘Hey, there’s this new singer out there named Elvis Presley and he’s really cool.’ The deep meaning of rock ’n’ roll was suddenly that young people had their own music, so to hear this guy singing, and to see what it looked like, it was just mind-blowing.”

Having only heard his parents’ music – the South Pacific soundtrack and the Nutcracker Suite were two regularly-spun records at home – this new style was a revelation for the young Lindsey. Then came Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Johnny Cash and more, and a chord book that allowed Buckingham to work out their music, spending hours in Jeff’s room with his singles and turntable.

“I wasn’t looking at Elvis like ‘I wanna be that’,” says the guitarist. “It wasn’t the iconic James Dean look that was drawing me, it was more just the overall presence of what it seemed to represent: the freedom, the possibility, the freshness. He was such a role model, with his Martin guitar – the whole package was just so incredible.”

While he now appreciates Scotty Moore’s picking and “orchestral technique”, Presley’s lead guitarist passed Buckingham by at the time. He took more notice of fingerstyle playing when he got into the folk music of The Kingston Trio, as well as jazz guitarists like Charlie Byrd.

“There was something identical that was drawn from for both of those styles. Some of those people were playing in a light jazz, sort of classical style, and I was trying to learn some of those things which inherently needed to be played with all the fingers. Even more fundamental was when that first wave of rock ’n’ roll started to fall away in the very early 60s, and folk music became really, really popular. Folk music was all about the Travis pick, or even banjo picking, and folk became a really big influence in my life, groups like The Kingston Trio or Peter, Paul & Mary, maybe Ian & Sylvia. This all predated Bob Dylan. He came in very near the end.”

Right hand man

That melting pot of fingerstyle influences led to Buckingham’s unique way with his right hand; more of a percussive hammer than picking, according to Lamendola.

“I was playing banjo too by that point,” says the guitarist. “It was just part of my style. Of course, I use a pick in the studio sometimes to get a nice clean sound for a strum, but that style is part and parcel with someone who teaches themselves how to play and doesn’t feel there are any rules they have to adhere to.”

In the 60s, Buckingham’s most high-profile gig was as bassist in the band Fritz, but by the early 70s, he and the group’s vocalist, Stevie Nicks, had set out on their own path as duo (and couple) Buckingham Nicks. For this move, the guitarist needed to hone his songwriting, which he did with a reel-to-reel in a storeroom at his father’s coffee roasting plant just below San Francisco, and develop his style on electric.

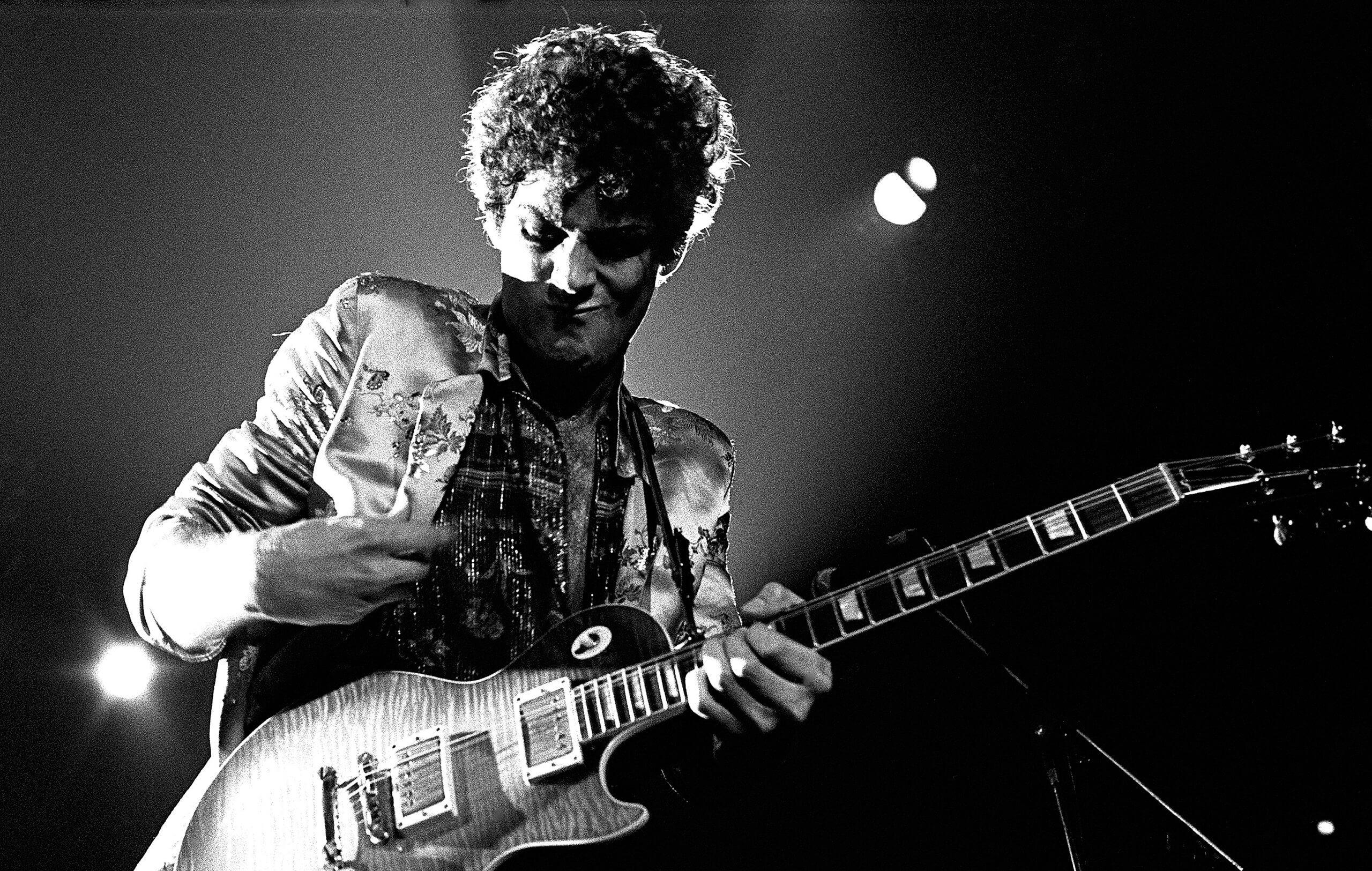

“I love that Peter Green stuff, But it wasn’t me. So it was an odd thing, to go and be the player of those songs”

“I wasn’t really a lead guitar player,” he says. “So in the process of retooling myself for Buckingham Nicks as the guitarist, I was listening to Jimmy Page a lot – he had great chops, but also amazing production values, and that became the key, just listening for the use of guitar in ways that were integral. I can’t think of anyone who even touches Jimmy Page in terms of being able to draw from elements of folk and classical and other things and make it so musical. So I guess that became a touchstone for me.”

Buckingham’s new Fender Stratocaster became his tool of choice, as it gave him impact and brightness even while using his fingers, but he also utilised a Gibson Les Paul on the duo’s self-titled and sole album, released in 1973 and still one of rock’s great out-of-print albums.

“The Strat gave back a lot for someone who wasn’t using a pick and therefore was looking for a certain amount of bite naturally in the sound of the guitar. As far as a reissue goes, 10 gears ago there was some optimism that Stevie would wanna play ball, but she apparently didn’t. You never know.”

Big shoes

After Mick Fleetwood heard Buckingham Nicks’ epic closer Frozen Love by chance in LA’s Sound City studio, he took the duo on as new members in Fleetwood Mac at the end of 1974. Seemingly never one to lack confidence, Buckingham found joining the band, and stepping into a role once occupied by the likes of Peter Green and Danny Kirwan, fairly undaunting.

“I had, and have, great respect for Peter and Danny, but I never had the sense of ‘Oh, I’m in the shadow of Peter Green’, or ‘I’m in the shadow of Danny Kirwan’. They hadn’t been around for a while anyway, and there’d been so many other incarnations of Fleetwood Mac. There was a sense that they were in the rear-view mirror, while the band kept coming up with album after album that were kind of non sequiturs, with different lineups all the time. That was just Mick’s way of keeping the band together and intuitively knowing there was something important at the end of the rainbow, which, obviously, there was.”

Joining Fleetwood Mac wasn’t without its challenges. With little material of their own, the new lineup still had to please fans by playing older Mac songs, such as Oh Well, The Green Manalishi (With the Two Prong Crown) and Rattlesnake Shake, along with a couple of Buckingham Nicks tunes.

“I love that Peter Green stuff,” he admits. “But it wasn’t me. So it was an odd thing for quite a while, to go up there and be the mouthpiece, be the player, of a group of songs that I had nothing to do with. Suddenly it did feel like I was in a cover band, and that lasted for years, because it took a long time for us to have enough material of our own to fill a set. It was something I came to think of as dues that I needed to pay as the new kid.”

Point the finger

Buckingham’s sound and gear choices were also questioned by the group, with Mick Fleetwood even asking the guitarist to stop playing with his fingers, a request Buckingham ignored. A change from the Stratocaster was deemed necessary, though, to meld with the band’s darker textures.

“They had a pre-existing sound,” he explains, “and the Stratocaster did not fit into that, so I had to start using a Les Paul. But being really full, it was not nearly as percussive or clean as the Strat had been, and it wasn’t as well suited for fingerstyle.”

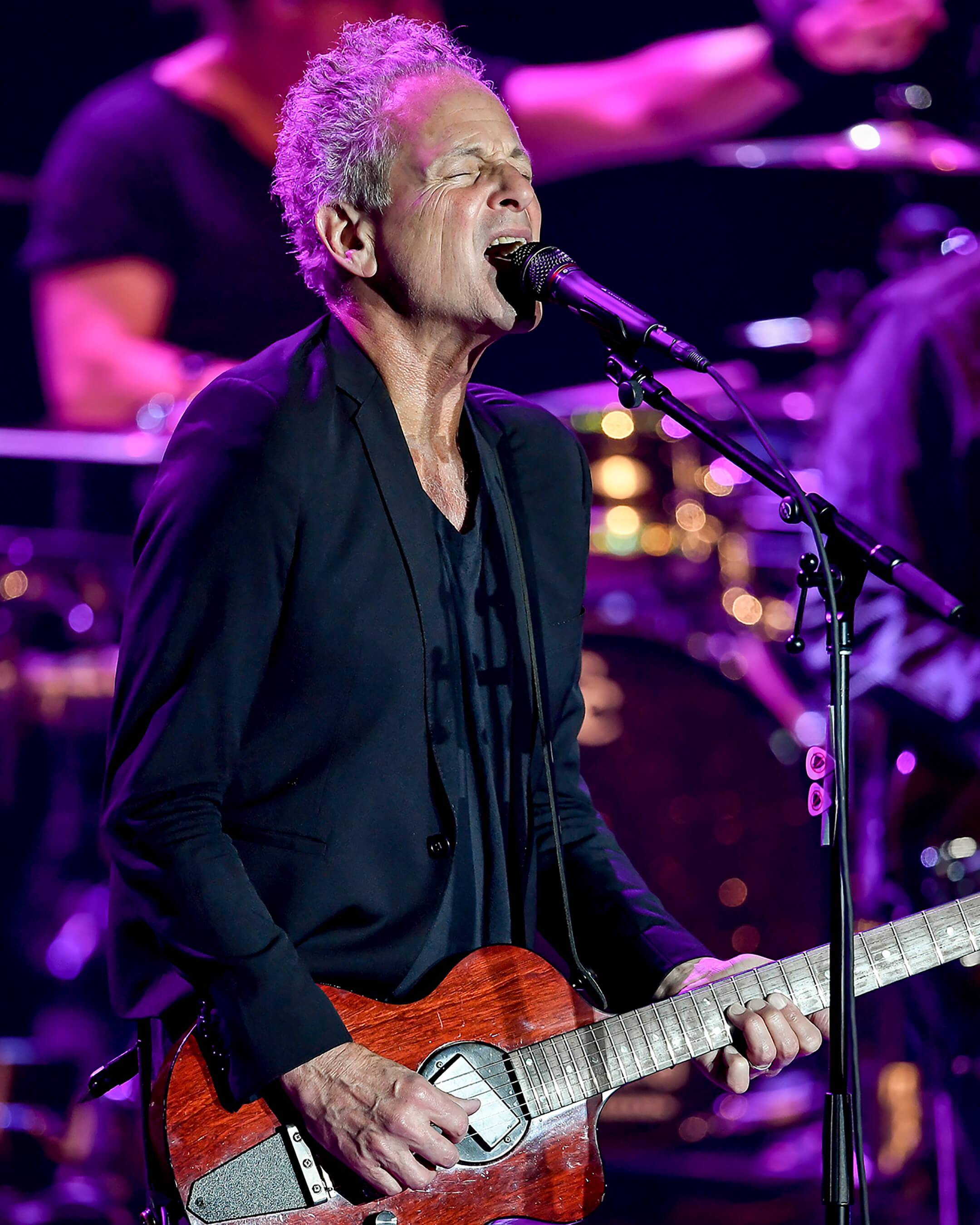

A solution was found by luthier Rick Turner, co-founder of Alembic, who had previously fitted an Alembic ‘Stratoblaster’ pickup into Buckingham’s Strat during the making of 1977’s Rumours. Two years later, he designed the Turner Model 1 especially for the guitarist: boasting the full Les Paul sound but with a more percussive, cleaner sound reminiscent of a Strat and also the possibility of more acoustic-like tones, it’s been the guitarist’s main onstage electric ever since. Currently he owns eight, with another on order from Turner, plus a similar number of acoustic Renaissance guitars, some baritone, also made by the luthier.

The Model 1’s construction was, says Buckingham, a simple process, as far as he was concerned anyway. “Did I have to go back and forth with Rick?” he says. “No, not at all. I just showed up one day, and that was it. It was like, ‘Wow.’ I don’t know how Rick managed to work that middle ground for me, but he understood how to translate that into what I needed technically.”

“my RICK Turner guitars have become such a part of the stage. I can’t imagine having been as effective without them”

The Model 1 isn’t, of course, your standard guitar – one of its features is that you can rotate the pickup to get a unique sound. In typical no-nonsense style, Buckingham and his tech found the place where they like it – “closer to the bridge on the low strings and closer to the neck on the upper strings” – and keep it there on all their guitars.

In the studio, Buckingham rarely uses the Model 1s, but live they’re essential to his performances: “They are so across-the-board useful onstage.” He runs them through vintage Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifiers, custom-made 2x12s with EV12L speakers, and sticks to the same two pedals, a Boss DD-3 delay and Boss OD-1 overdrive.

“I always need to have both of those,” he says. “Certainly you can’t play a lead without fuzz. I’ve tried other things that were interesting but not necessary, so I just kept to what I had. After a while, you become a creature of habit. Maybe it would have been different if the format in Fleetwood Mac had been a little different – you know, if it was as open as, say, what The Edge has, the space around his guitar playing. He’s got a lot more volume to fill, and perhaps freedom because of that, whereas there’s always going to be an element of needing to fit into something that is somewhat confining in Fleetwood Mac.”

Going alone

Any discussion of Fleetwood Mac is delving into the past, of course: Buckingham is now a full-time solo artist after being ousted from the band in 2018, seemingly for requesting a few months’ delay to a suggested tour. “It was absurd, after all the troubles we’d been through,” he marvels. Today he seems freed creatively by the return to his solo work, and his new record, Lindsey Buckingham, marks a new phase even as it continues the experimental pop-rock of 2011’s Seeds We Sow.

Some artists thrive on collaboration, but Buckingham adeptly handled everything on the album himself, from playing every instrument to engineering, producing and mixing in his home studio. “I recorded it on an old Sony 48-track reel-to-reel, but it’s getting hard to find tape for it! I had this one attempt at learning ProTools but I picked the wrong time – I took a unit out on the road with Fleetwood Mac but it wasn’t the environment for me to really take it in. I should have learned ProTools years ago, because it’s right up my alley.”

There’s a modest amount of gear in his home studio, but it’s all equipment that Buckingham knows inside out, allowing him to work quickly and intuitively. Not that he knows the names of most of it: “Do you want me to walk out to the studio and look? I just don’t register this stuff, I’m so non-technical, you know…”

Once in the studio, Buckingham reveals that he plugs his Stratocaster straight into the tape machine, sometimes through a Radial Firefly DI box. His Martin, Taylor and Turner Renaissance acoustics are both direct and mic’d, while for leads, such as the screaming solos that close On The Wrong Side and Power Down, he uses a Roland Guitar Synthesizer. “It’s direct, but it sounds like you’re going through an amp turned up to 11. Back in the old days, I might have gone back to a Les Paul for a lead.”

Other effects, primarily his favourite, delay, are provided by rack units, the Alesis MidiVerb 4 and Lexicon PCM 70. Perhaps it’s no wonder that Buckingham has forgotten some of the details of his gear: the album was recorded in 2018, but its release was delayed by emergency heart surgery, resulting damage to Buckingham’s voice and the small matter of a global pandemic. The guitarist is delighted that it’s finally coming out, though, and even keener to get back on tour. Due to the number of different tunings he uses, he’ll be accompanied on the road by every Turner Model 1 he owns, plus seven Renaissance acoustics and four Taylors.

“There would be riots if I didn’t play any Fleetwood Mac,” he says, “but beyond that I have no idea what the set’s gonna be. It all seems so intangible to me because it’s been so long. But my Turner guitars have become such a part of the stage. I can’t imagine having been as effective without them, you know?”

During the pandemic, Buckingham has laid pretty low – he’s played guitar so infrequently that his callouses are gone – but he’s started looking to the future again, and has even snuck back into his home studio to lay down some new material.

“There were quite a few months where I didn’t do much of anything, but finally I finished a couple of new songs in the studio. That’s about it, I’ve only done two, but I’ve got a bunch of other ideas and a bunch of voice memos on my phone of me humming, ideas I could be working on. I’d not been overly motivated to do too much, but I finally said, ‘I gotta go reclaim my discipline.’”

Lindsey Buckingham is out 10 September on Reprise Records/Rhino.