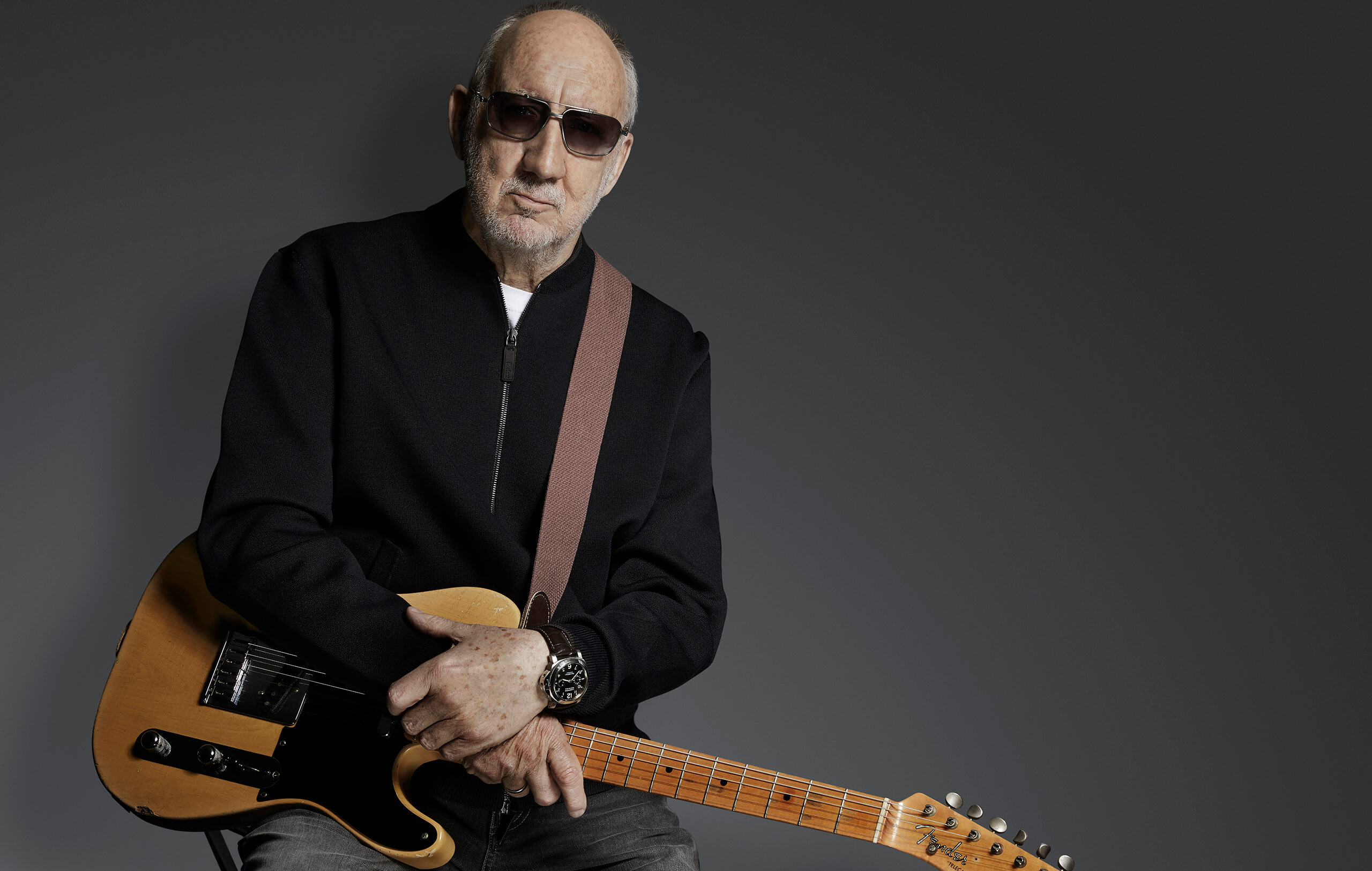

“I’m still having fun with guitars”: Pete Townshend on Clapton, Hendrix, The Who and coping with lockdown life

As The Who’s guitar-smasher puts the finishing touches on a box-set for his first concept album The Who Sell Out, we caught up with the 75-year-old to look back at his memories of that time, his lockdown-induced GAS, and why guitars are rather like puppies.

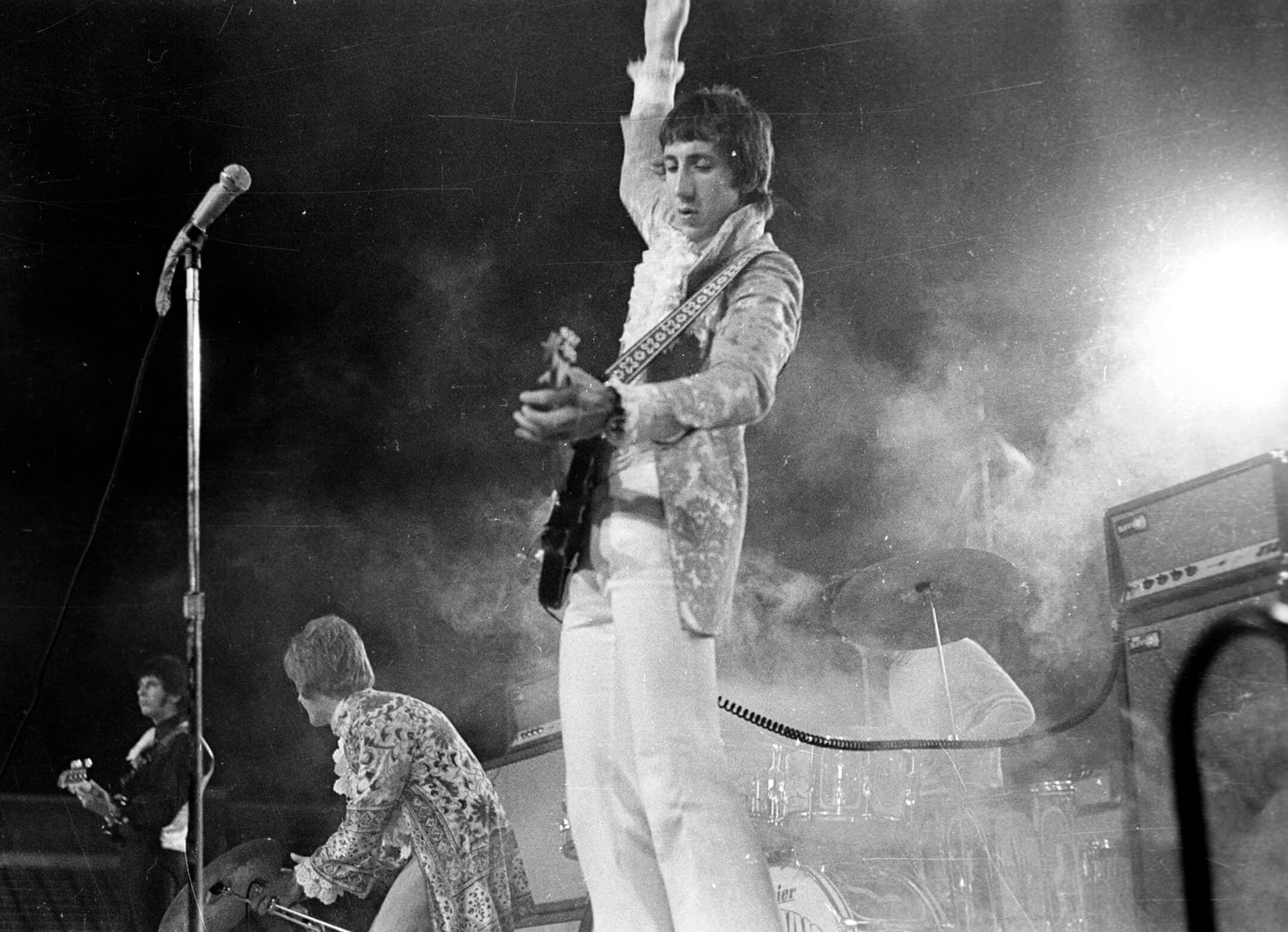

Image: Tom Wright

“You’ve turned into a fucking stoner, that’s what’s happened.” This writer has known Pete Townshend for nearly 30 years, so when we explain that we’ve been whiling away the lockdown hours building and rebuilding guitars, including a scratch-built Robbie Robertson, Last Waltz-style bronze Stratocaster, he can barely contain his mirth. But despite his guffaw at our quarantine projects, Townshend can relate – despite being one of the most influential guitarists of all time, like many of us mere mortals, The Who’s primary songwriter found himself bitten by the guitar bug anew during the past year, and he’s been shopping…

“I’ve been in the studio, designing studios, taking studios apart, fiddling with new gear, and buying and selling guitars,” he tells us. “I didn’t buy anything great. I bought an old Harmony three pickup, and a Harmony 12-string, which is unplayable, because I’d sold mine at auction in Chicago to Eddie Vedder and always wanted it back.

“I bought some very old Rickenbackers, which are sometimes good and sometimes bad, and I bought a really nice Gibson 335. It looks like shit, but it’s really good. I’ve used that on a couple of tracks.”

Proof then, that in these unique times, even rock gods find comfort in that universal of guitar-related therapies – GAS.

Before the aforementioned pandemic and lockdown, Townshend had been set to have a busy 2020. He’d toured the world in 2019, recorded and released WHO, the first new studio album by the band since 2006s Endless Wire, as well as a novel, Age Of Anxiety, and was set to hit the road again, for one of the longest treks of the band’s career.

“I was exhausted,” Townshend says flatly, and admits the lockdown was, at least at first, a relief of sorts. “I’ve been good, though, and as busy as I’ve wanted to be over the past year, which has been sometimes really busy and other times not so much. I’ve had a few ups and downs emotionally, just like everyone, but I’ve been good, and very happy not to be on tour. Now, after a year of it, though, I’m sort of missing people very much.”

Out and out

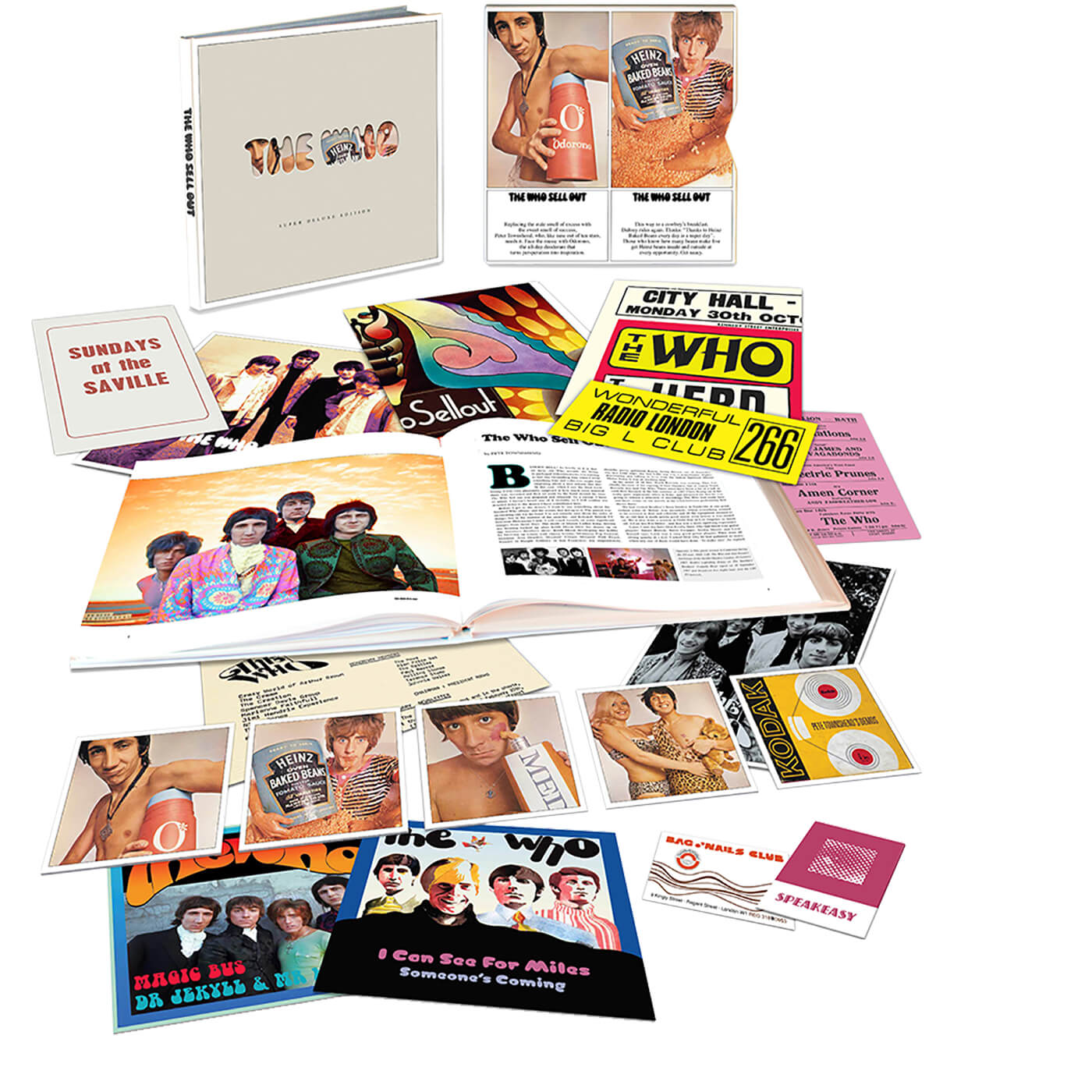

With in-person interviews off the table for the foreseeable future, Townshend is calling from his Richmond home to discuss the new super deluxe, greatly expanded edition of The Who’s third album, the remarkable and ground-breaking The Who Sell Out, from December of 1967.

It was an album born out of necessity, but that grew in stature almost immediately after its release. Faced with an imminent deadline for an album that in Townshend’s mind he hadn’t even really begun to write from his then-manager – and label boss – Chris Stamp, who had compiled a rag tag bunch of recent studio recordings into a possible release, the pair hit on an inspired idea: they’d riff on the then-current pirate radio craze, and would cut jingles and station IDs to link the tracks together, in turn creating a cohesive and, hopefully, coherent whole. It would also take some of the weight off Townshend as the band’s songwriting and creative driving force, as it would allow him to enlist his bandmates – and most especially bassist John Entwistle and drummer Keith Moon – to assist with creating those jingles. Maybe even, he and Stamp thought, they could sell the jingles as advertising time to unsuspecting brands hoping to cash in on the bump in publicity they were sure to get.

Though selling the ad time never happened – in fact several brands threatened to sue the band as a result – the jingles turned out to be an inspired way to stitch together a disparate bunch of tracks, and created what could rightly be called the one of the very first actual concept albums.

“We didn’t make very many albums,” says Townshend. “This was one of the very good ones.”

The new box set – all 112 tracks and two 7-inch 45s of it – include the album proper in both mono and stereo, as well as the band’s singles from the period, recordings that went unissued until 1974s Odds & Sods release, electric session tracks that show a band having a blast and hardly at the breaking point that history would have us believe, and a healthy helping of Townshend’s home demos from the period.

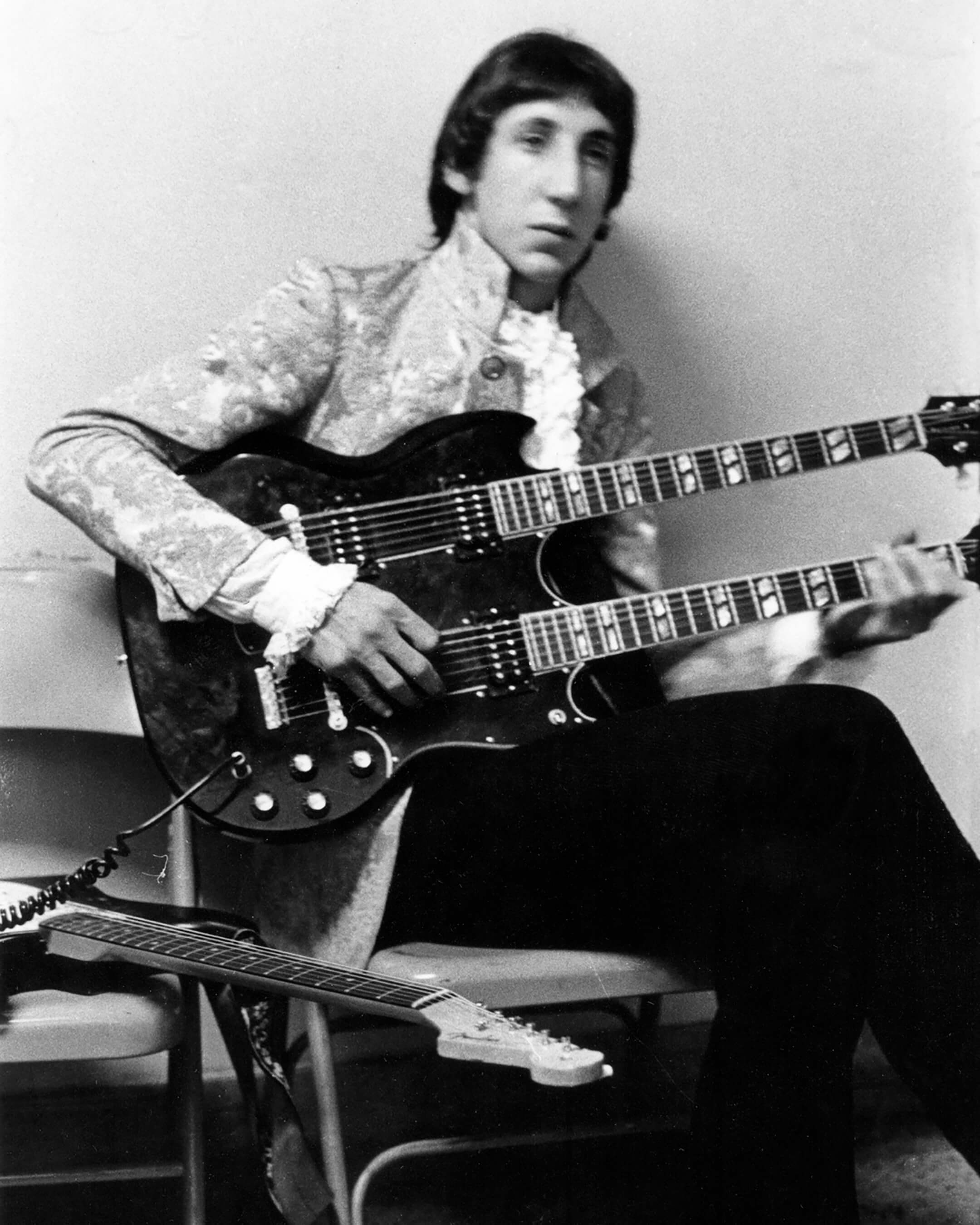

“It was an incredibly primitive process,” he says of the recordings, which show Townshend in full creative flower, just months before he would begin to tackle his next work, Tommy. “My home rig at the time was just a small Fender amp – a tiny little amp with a 10-inch speaker in it and three knobs. And I used to take my stage guitar home; whatever it was I was using at the time. So often, it would be a Stratocaster or an SG.”

Like his friend and contemporary Jimmy Page, Townshend has one of the keener memories in rock ’n’ roll, and is quick to clarify when we mention the generally accepted wisdom that his set-up of the time typically included a Fender Stratocaster (which usually had a mere seconds to live, owing to Townshend’s embrace of the auto-destructive art ethos he learned from Gustav Metzger at Ealing Art College) and the first ever Marshall stack.

“I was using Stratocasters,” Townshend says. “But it’s a misconception that in that period I would’ve been using Marshall. I used Marshall for a while, but then I hit on Sound City, which eventually became Hi-Watt. I preferred those because they produce really intense treble. And prior to that, even when I did use Marshall amps, I used to use Grand Prix reverb boxes to create distortion and treble. But on tour in that era, I was actually using Beatles-style Vox amps. They were tube amps, but they were very poorly made. I used them right the way through – or halfway through – the Herman’s Hermits tour of America, when we did a deal with an American guy from Sunn Amps. I never really got on with them, so I used to kind of goof it a little bit, the sound they got. But I didn’t care much about the sound at that time, anyway.”

“Sometimes CREAM sounded so empty. I thought IT would’ve been much better if they had a Hammond player”

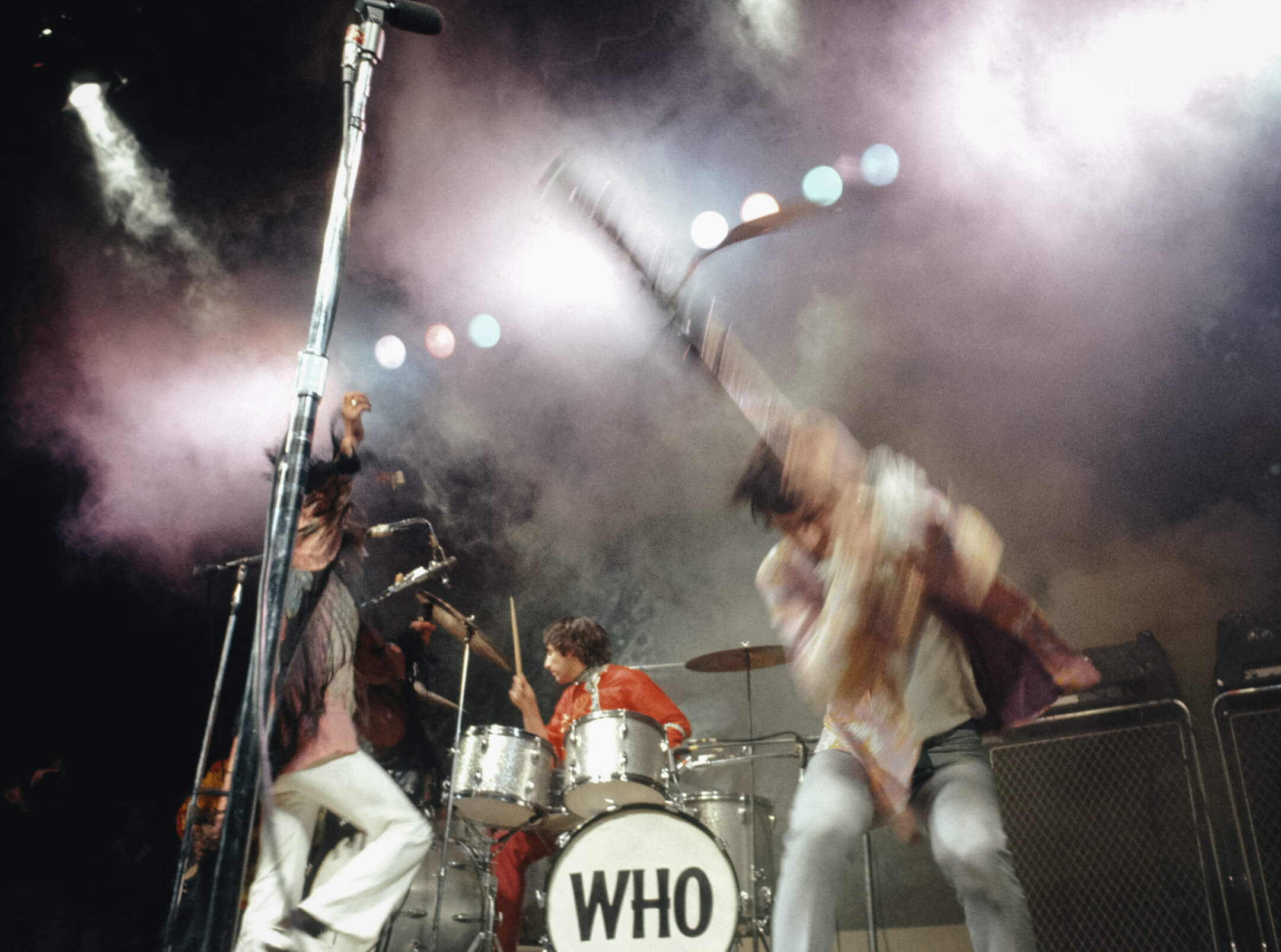

Townshend is also quick to correct any misconceptions as to who the onstage driving force of the band was, despite The Who’s drummer having a legendarily kinetic style.

“I hate to hear you say that I was riffing off Moony, because I think that – partly because of his drumming style – I had to play a really, really solid, tightly syncopated, but nonetheless tightly metronomic style of guitar playing. I was driving him rather than him driving me,” he says.

That requirement, as well as the fact that The Who were essentially a three-piece band, also, he says, drove his development as a guitar player.

“There was no space, really, for fancy leads,” Townshend explains. “As soon as I started playing single notes, everything seemed to fall apart.”

To Townshend’s mind though, this was a problem that didn’t just plague The Who at the time, and he recalls seeing his friend Eric Clapton suffer similarly even when surrounded by supergroup bandmates, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker

“I have to say, that was my experience listening to Cream,” Townshend recalls. “It felt to me that sometimes it sounded so empty. I thought they would’ve been so much better if they had a Hammond player. I always loved Eric’s playing, but not always his sound. It always felt to me like it was a bit muffled, in the Marshall days. That’s why I prefer Traffic and Blind Faith. I like the sound of that.”

Some players are effervescent enough that they transcended the limitations of gear and line-ups, however, and so it’s perhaps unsurprising that another of his contemporaries, Jimi Hendrix was, even in Townshend’s mind, on another plane.

“Hendrix, although he played single lines, he was such an elegant, remarkable, decorative player as well, and just in a different league, I think,” Townshend says. “I’d like to say I was influenced by him, but who in their right mind would back that up today – even some of the shredders of the modern world – and say they could cover what he does?

“And even if you can, you can’t make it speak the way he did, and of course, the other thing, which is not shared often, which is unless you were there, you kind of missed 80 to 90 per cent of where the magic was. He was just such an extraordinary presence once he walked onto the stage with a guitar. It was kind of weird. It was almost like he was some kind of angelic, seismic, metaphysical force, who seemed to have light rays coming out of him, and then, as soon as he walked offstage, it would switch off. He was an extraordinary presence. And that definitely made what he did as a player penetrate in a soulful way as well as musically. So those early recordings – they were great, of course – but I always felt they were missing something. Like they’re missing one bite of magic.”

Record breaker

There might not have been room for too much fancy lead playing in The Who, but one thing they had in spades was volume – famously being declared the “world’s loudest band” by the Guinness Book Of World Records at one point.

“The main thing about me trying to get a stage sound at that time, and also, of course, a sound that I could develop in the studio, was that there were no real effects available,” Townshend reflects on his live sound at the time. “There were no stompboxes, really, that were any good. There were a few around that all just made the same fucking racket. But there was no sinuousness in the sound. There was no dynamic, there was no sense of change in the sound. Jimi used them effectively, but Eric didn’t. Eric’s sound was Eric’s sound, and the way it started the evening, it would end the evening exactly the same way. It was the notes that mattered, not the sound. I was interested in sound. In huge, changing sound.

“So, the thing about the SG plugged into the Sound City amps was that, with the P-90s flat out, it was this incredibly grungy but very, very solid sound. But when you turned the guitar down, instead of going soggy and soft, it got bright. You can hear it on the live recordings of The Who, where I stop the band and I start to noodle around. The sound is like an acoustic guitar.”

Plenty of us have spend a lot of time noodling around ourselves over the last year, though to much smaller audiences, but asides from the work on The Who Sell Out, Townshend has been keeping himself busy working on new material.

“Along with all the archival work I’ve been doing, I’ve been working endlessly in the studio,” he confesses. “In there I generally just end up using a stage guitar, especially when I’m working on playing heady sort of guitar on a recording. And because I’ve got quite a lot of studios spread around, I’ve got about 10 J-200s, the ones with the tune-o-matic bridges. With a few exceptions, it’s still my go-to guitar for the studio, because I think the sound is not too full-bodied, so it’s easy to record. And I’ve got a really nice old Martin, too. Simon Law, who is now my guitar tech, who was employed by Alan Rogan, he’s turned out to be a real diamond. He’s a luthier as well, and rebuilt an old Martin 000-18, which I’ve been playing that recently and that’s just extraordinary, because I think two months before he worked on it, it was unplayable.”

“I’m still having fun with guitars. I’m still working out tunings and inventing tunings – I REALLY LOVE THAT”

It’s the second time that Rogan’s name comes up in our conversation, he sadly passed away in 2019, and it’s clear that this late, great tech to the stars is missed by those who knew and worked with him.

“Alan was very close to Eric Clapton, he was close to Keith Richards, he’d worked Tom Petty, and George Harrison, of course, whom he was very close to,” Townshend recalls fondly, while making the point of how crucial Rogan was to having around given the remarkable clientele he served.

“I don’t think he shaped my sound, but I had never had a guitar tech before Alan came to work for me. And I remember I used to give him a hard time, like, ‘Listen, the guitar tech is supposed to tune the fucking guitars, not just put strings on them, man’. So, Alan is probably one of the first guitar techs. I guess you can say I invented the guitar tech! Because I can remember going to see Crosby, Stills, and Nash in a session, and they were restringing their own guitars. Or, in Steven Stills’ case, he would only string some guitars, because there was this one Martin there that he said to me, ‘I’ve never changed the strings on this guitar, and I never will unless one breaks’ That was part of the sound of them.

“But, Alan was fabulous. He was a great energy, he was funny. And he had the biggest black book of beautiful women that I’ve ever seen. I remember being shocked at some of the women that he would wheel into dressing rooms. Like, hold on a minute. Who’s the star here?! Me!”

Texas pride

While nothing really seems sure any more, with the prospect of things returning to normal again means that Townshend can start to think about a gear-related perk of getting back on the road with The Who…

“Well, every time I pass through Austin, Texas, I go Collings to pick something up, and I’ve never really ever regretted anything I’ve bought,” he says with a laugh. “I’ve got 10 Collins of various sorts, including one with a very, very wide neck, which is great for fingerstyle and complex chords in the left hand. And I got some small bodies and some big bodies. What’s interesting about Collings is they’ve got the ex-Martin craftsmen milling about, and they’ve got the most fantastic supply of timber.”

Warming again to the guitar-shopping theme, we recount an anecdote Jackson Browne once told about his love for scouring eBay for oddball vintage and Japanese guitars, and his love for 80s Yamaha acoustics.

“I bought a Yamaha acoustic, brand new, when I had a place in Cornwall 20 years ago,” Townshend responds. “I went into a local guitar shop because I needed a guitar, and I bought a Yamaha 12-string. It was a Japanese guitar – or possibly made in China – and it was just okay. And now, I have it in my house and it is absolutely amazing and it’s because the wood has dried out.”

Other guitars, he says, no matter their pedigree, don’t always age so well, though they do have personalities of their own.

“I can remember the J-200 that I gave to the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame, the one that I wrote Pinball Wizard on, and lots of other stuff, and that I made all the demos from that era on, which I bought at Manny’s,” he says. “Before I sent it off, I opened the lid and it looked like the guitar was dead. All the varnish was peeling off. So, I packed it off. It was probably perfectly okay, and just needed a wet blanket put over it.

“But I think what’s interesting is that guitars do change. I think they also need attention. I think you’ve got to keep your guitars out. It’s not good for them to be stored away. Even if they’re just sitting there on stands, they can get over-dry and warped, but at least they’re there to be picked up. It’s a bit like puppies. We’ve got five dogs, and what I know is that when you go up and you say hello to one dog, the other three look at you as though they want to kill you. I think guitars are like that. You pick up the guitar and, ‘Oh, this is great, I’m going to record with this!’ And then all the other guitars are in the back of the room going, ‘You bastard! You wait till you pick me up!’

For Townshend then, his love for his first and favourite instrument remains an ongoing affair.

“I think it’s incredibly personal, working on guitars,” he begins. “It’s like how sometimes, if you just tidy up your stuff, you’ll be bursting with creativity. I think it’s the same with instruments. You get them in order, and they immediately inspire something. So I’m still having fun with guitars. I’m still working out with tunings, and inventing tunings, and even re-entry tunings, where the strings are higher at the top than at the bottom. I really love that. So, I’m still having fun with guitars.”

As we wrap up our long conversation, Townshend becomes reflective about the past year, if with an eye toward a future that feels more than ever unknowable.

“You know, I’m not unbreakable, I’ve had some bad days and I’ve had some weird times,” he says. “But I’ve gotten to spend so much time either in my studios or – what I feel is a key part of my creative process, creating studio rigs and setups; my Brian Eno side, if you like – and then composing, too. So, for me, I was very, very happy for the first six months of the lockdown. I did three or four months in the studio writing, composing, and working with a couple of other artists, because the lockdown wasn’t absolutely extreme at first. Then, and just before Christmas, we hit another very extreme lockdown. I think, then, I found it a bit strange, the idea that it was going to be yet another year, really, before the music business found its feet again. And here we are. We still don’t know, do we?”

The Who Sell Out Superdeluxe Box Set is released on 23 April on UMC/Polydor.