“It’s kind of an accident and that speaks to the way we did things as kids”: punk legend Brian Baker on his new band, Fake Names

When you’re an elder statesman of punk rock, founding member of Minor Threat and guitarist in Bad Religion, what motivates you to keep starting new bands well into your fifties? For Brian Baker, Fake Names was born out of the simple desire to hang out with his friends.

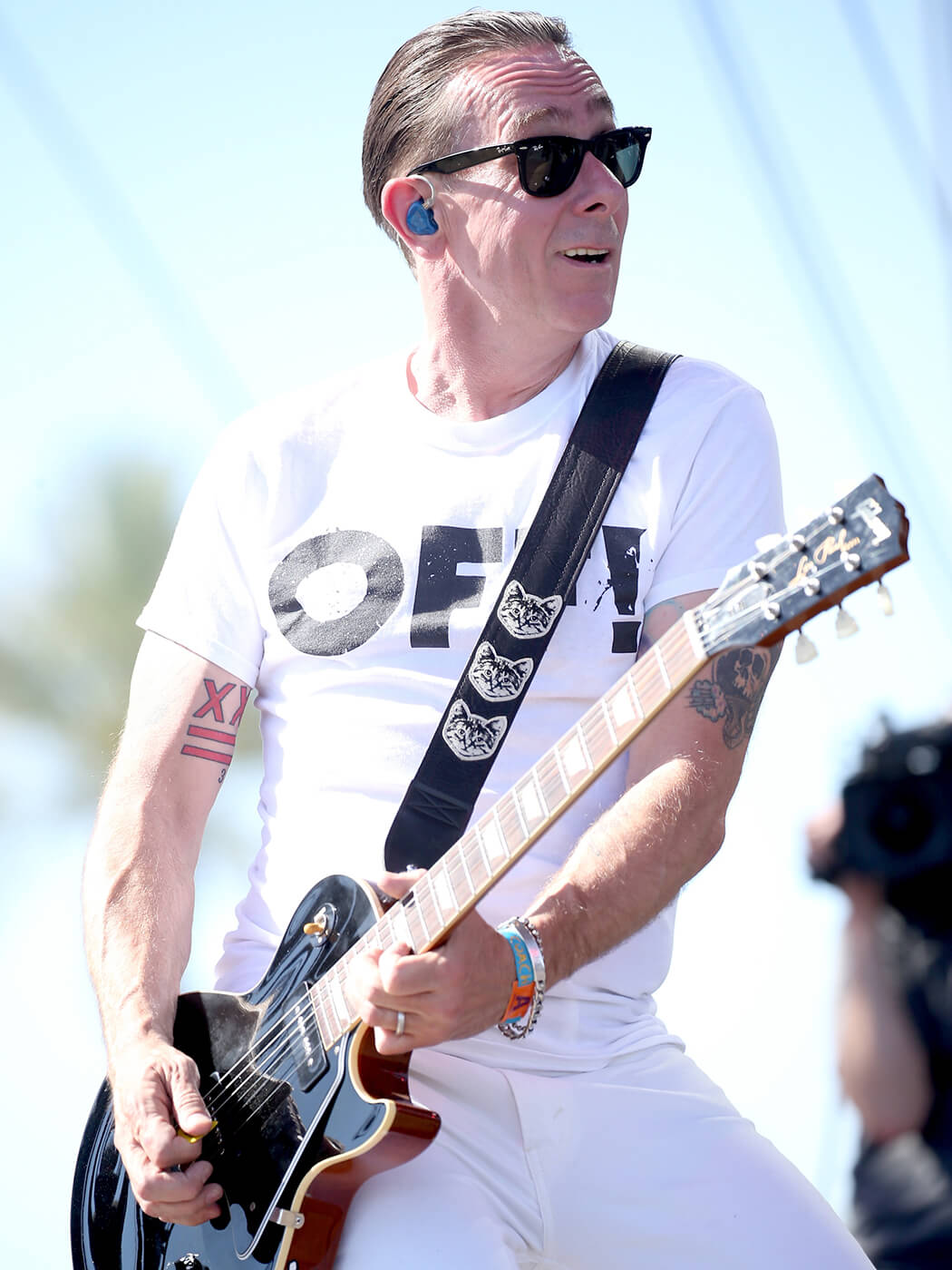

Brian Baker of Bad Religion performs onstage during day 2 of the 2015 Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival (Weekend 1) at the Empire Polo Club on 11 April 2015 in Indio, California. Image: Matt Cowan / Getty Images

An important facet of rock kayfabe is the idea that origin stories are worth listening to. Pull back the curtain, though, and you’ll find a thousand variations on people meeting at school, in college dorms, or while bouncing between bars. Brian Baker’s been in the game long enough to dispense with the subterfuge when discussing how his new band, Fake Names, came to be. “The idea was to hang out with Michael Hampton because I’d moved to New Jersey, and he lives in New York,” he says. “This guy’s been my friend for 40 years, even longer. Can you imagine that? That’s all this was: Hey, you wanna get lunch and play guitar?”

But Baker and Hampton aren’t just old friends out for a nostalgic hang. Since 1994, Baker has played guitar with Bad Religion. Prior to that he was a pillar of the Washington DC punk scene, serving time with melodic hardcore greats Dag Nasty and, as a teenager, playing bass in Minor Threat, one of the most important bands in underground history. Hampton, meanwhile, once flanked a pre-Black Flag Henry Rollins in SOA. before playing guitar in Embrace, the hugely influential proto-emo band fronted by Ian Mackaye between gigs with Minor Threat and Fugazi. They are part of the fabric of alternative music in America.

Filling out the Fake Names roster on their self-titled debut are Refused’s Dennis Lyxzén on vocals and another former school pal in bassist Johnny Temple, of Girls Against Boys. Appropriately, the group channels the easy chemistry of lifers who helped build punk and, particularly in Lyxzén’s case, devoted subsequent decades to interrogating the artform. Not that Baker would put it that way. “How we wound up making this record is very much like my early career in that it was basically just whoever walked into the room, like ‘Oh, hey Dennis do you want to sing?’ There were no real expectations,” Baker says. “That’s just like D.C. hardcore. Nobody knew anybody would care.”

Home studios

Sequestered at Hampton’s home, the duo worked on song fragments and riffs plucked from voice memos. Eventually, Baker found a sense of validation as ideas that he’d cast aside were retrofitted to bring into focus a picture of hyper-melodic songs informed by the reedy, straight up tones of classic British power-pop. “Michael could take a riff that I thought was junk and turn it into something really clever,” Baker says. “He’s an excellent composer, but he’s also got fresh ears. To see that happen over and over again inspired me. There was something electric about this combination. That is why we said, ‘Look, we’ve got to put a band together and play this out.’”

Their next step involved booking demo time at Renegade Studios, the New York recording space owned by Steven Van Zandt, Bruce Springsteen’s long-time lieutenant in the E-Street Band. With time at a premium, Baker and Hampton settled on a pedal-free, no frills style that prioritised their own enjoyment. “We wanted to make it so that nothing we played in the studio couldn’t be reproduced live,” Baker says. “To that end, instead of having a delay on a guitar part we thought it would be much more fun just to play the guitar as if it had a delay.

“You would ape the sound of an effect by the way you pick the strings and use your hands. It’s entertaining and it became kind of a schtick we got into when we were first writing at Michael’s because we didn’t want to use a bunch of plugins. His fucking computer is so old that every time you try to put something in the stack in ProTools the thing crashes.”

Bare bones

With engineer Geoff Sanoff and Hampton co-producing, the studio setup was similarly bare bones, even if the desire to take a detour through classic rock history was always lurking just out of shot. “We had a good Marshall half-stack, just a JMP 100, and a reissue hand-wired Vox AC30,” Baker recalls. “I mean, I’m in Little Steven’s studio, where a lot of his equipment is stored in a sort of ramshackle way. So you could walk into this back room and dust something off and go like, ‘Oh, look at that. It’s a 1953 Fender Champ.’ We did a little bit of that.”

Once the demo was down Baker got in touch with his Bad Religion bandmate and long-time Epitaph Records boss Brett Gurewitz, hoping that he might be able to suggest a cool indie label who’d be interested in eventually putting out a Fake Names record. Instead, Gurewitz immediately jumped on it. But he had a curveball up his sleeve: in his opinion, these demos were the record. “It was as much of a surprise to me as it was to you,” Baker admits. “I wasn’t thinking about it on a grand scale, like Brett would want to sign us to Epitaph or I’ll call Ian at Dischord and it’ll be Dischord #220. I just didn’t think that way.

“Our demos were not just home created – we were in a really great space with an experienced engineer – but it was still just us capturing ideas. There was not a lot of time spent sitting back in chairs and imagining what could be. We just put down what we were playing in the rehearsal space. I think that’s part of why this is so cool – it’s kind of an accident and that really speaks to the way we did things as kids. Back then there was no such thing as a demo. When you went to the studio that was your record. Unknowingly, we did the same thing.”

This twist in the tale also meant that Baker and Hampton ended up tracking their album with a motley crew of guitars that they felt comfortable with or excited by, which feels apt in hindsight. “Michael has had the same guitar since 1981,” Baker laughs. “He has a really weird black Gibson SG that was made for a few years with Moog electronics installed in it. Michael played that same guitar he’s had since he was 16, but this was an opportunity for me to bring in a lot of stuff that really hasn’t been useful for Bad Religion. I’m so fortunate to have a 1957 Les Paul Special. It’s all original, really straight, and just sounds beautiful. I also have a Nash Esquire and a really neat Rickenbacker 330, which I never get to play. The only thing that’s really special about it is that it’s all gold, which is why I bought it. You know, Paul Weller, gold Rick. Gotta have it.”

Zooming out

Fake Names is an understated joy of a record lit up by the lived-in interplay of its serrated lead lines and Lyxzén’s impassioned bark, and its success stems from the fact that its origins were low stakes. It’s not going to change music in the way that its authors did when they were young men, but it doesn’t have to. These days Baker is able to zoom out and see Minor Threat, and Dag Nasty’s role in DC’s Revolution Summer of 1985, as important cultural moments divorced from the fact that his lived reality of them was as a kid playing loud music in the basement at a friend’s house. “I get it now. That’s the benefit of time,” he says.

“I think one of the reasons we know who Minor Threat are now is because Ian knew exactly what he was doing. He was trying to create a community. He was aligned with the same values and commitments that he still exhibits today. Now that I’ve stepped away from it, I see why it became what it did. I was not really aware that I was part of something that was well thought out. I didn’t even know what the lyrics were. I’m playing bass in a basement and you can’t hear anything and there’s a guy yelling. I’m not thinking about it in an artistic way. It’s just a fun thing to do – I’m wearing a jacket with names written all over it, I’m fucking with people who yell at me on the street. It’s that basic, beautiful thing when you first start out in punk rock.”

Fake Names capture some of that beauty in amber. The band’s heart is the relationship between two old stagers who haven’t lost sight of what it means to love each other’s company and the simple pleasure of making music that speaks to you on a basic, profound level. “It’s almost like time travel,” Baker says. “When I’m playing with Michael, it instantly takes me back to when we would play together, and I’m not joking about this, in first or second grade. We were playing acoustic guitars together at sleepovers. Going over to his house, with his wife and his children, we’re all adults now, but when we play it really does bring me back to the earliest days. It’s phenomenal, I love it.”

Fake Names’ self-titled debut is out now on Epitaph.