Related Tags

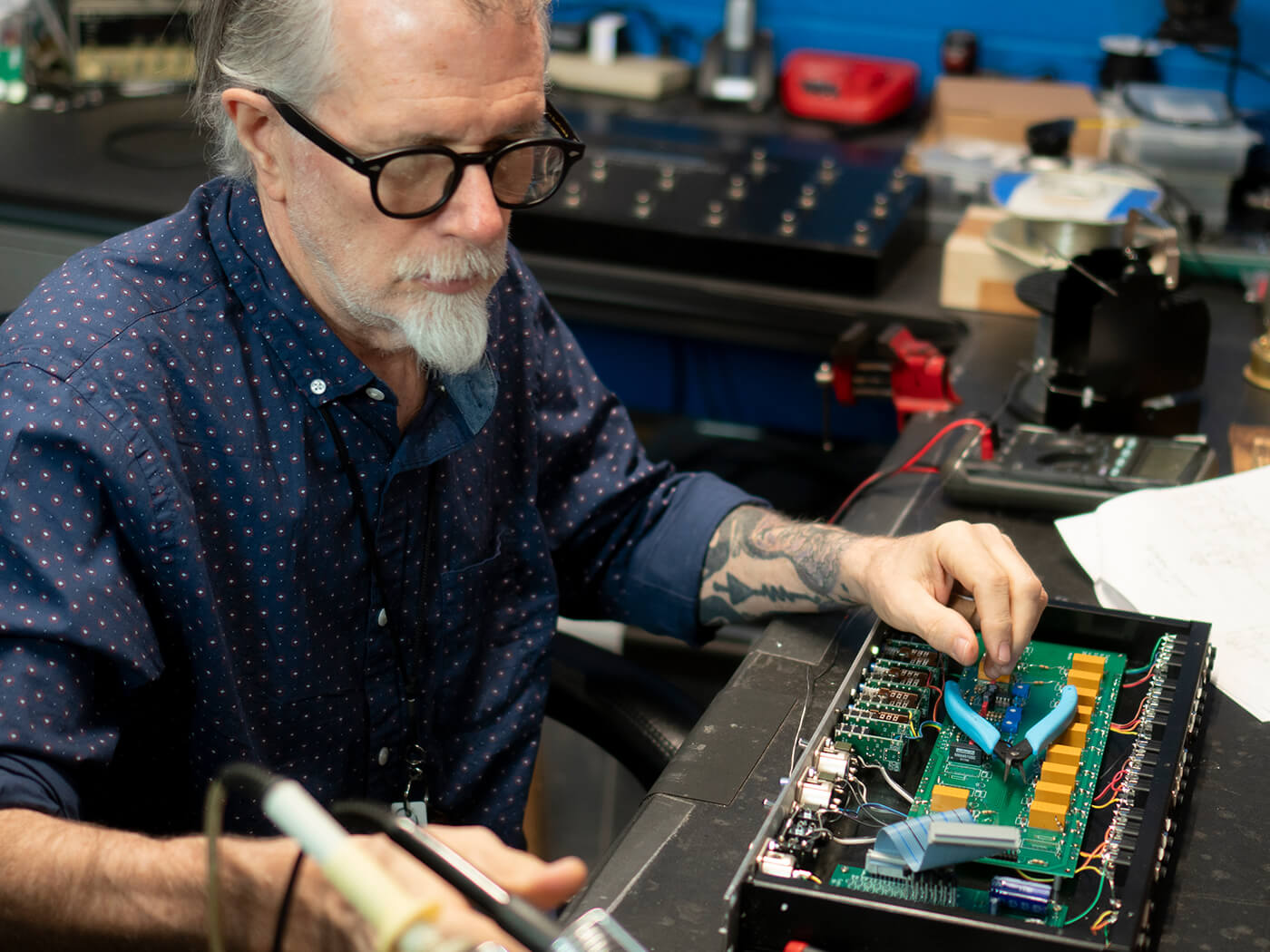

Meet Bob Bradshaw, touring rig maker to the stars

He’s set up rigs for everyone from Olivia Newton-John to The Edge to Yngwie Malmsteen.

For many guitarists who might like to think of themselves in, er, slightly hipper terms, the image of the rack full of effects processors, high-gain preamps and megawatt power amps is inextricably tied to the pointy guitars, spandex slacks and bouffant hair of the commercial-metal bands of the 80s and early 90s.

The truth is, far more artists than those of the strut and stride brigade were turning to such touring systems back when the rack promised to be the way forward. But in fact pro-rig pioneer Bob Bradshaw got into the game way before rack-mounted guitar FX were even a thing, and his craft has always been about finding ways to make guitarists’ stage systems work for them, using their preferred gear throughout the chain, rather than imposing any particular format upon his clients.

And if that pursuit has spanned one trend after another over the past four decades, it’s interesting to note how much of Bradshaw’s work has come full circle over that time. As he puts it: “Actually, it’s funny: what I do these days, I had those same concepts almost 40 years ago.”

Goin’ to California

Bradshaw moved to southern California in 1978 after graduating from electronics school in Atlanta, Georgia. After serving out his time with the company that had brought him west, Hughes Aircraft, he segued into his love of audio electronics in 1979 and took a job as a bench technician at Music Service Center in Santa Monica.

Although effects pedals were already common fare in the guitar world, the pedalboard was the newfangled way of merging a collection of more than two or three into a seamless stage accessory, but most practitioners of the art of creating the things were navigating uncharted waters.

“In the back of the repair shop,” he recalls, “was a guy who did the keyboard work and stuff, for Fender Rhodes and all these other keyboards. And then there was a synth guy, too, who was like the brainiac of the operation, because he was working on Moogs and early ARP synths and early Yamaha synths. Oh my god, yeah, these guys were brilliant! So the guy in the back – long story short – would get in pedalboards and he would work on them, which were very, very crude at the time.

“Paul Rivera was the king of pedalboards before I started, and sometimes his stuff would come in, and I’d see what he’d done. And he’d modify the pedals, put DIN jacks on them to carry power, or LEDs, and a lot of the pedals at the time didn’t have LEDs on them.

“So I was looking at this stuff, and at the same time I had these articles from Craig Anderton about remote-switching and stuff. It was somewhat crude switching using CMOS chips, and they were really low-headroom because they were logic chips; they could pass an analogue signal, but were very limited-headroom, and that’s what he spec’d out in that article.

“So I took that article and thought, ‘There’s got to be a better way to do this.’ I took that and started developing analogue switches based on discrete FETs and stuff, which made a huge improvement in their sound.”

Having gained his foundation at Music Service Center, Bradshaw founded his own outfit, Custom Audio Electronics, which rapidly became one of the world’s few genuine specialists in creating bespoke touring rigs. Essentially, his business involved making what were literally ‘multiple effects units’ out of guitarists’ collections of discrete effects pedals and the occasional Echoplex and the like – long before anyone had dreamed up the all-in-one multi-FX products of the future – and helping them play nice together in the process. That meant devising not only clever switching systems, but rectifying input and output impedances and level and gain mismatches, creating power supplies, and so forth.

This specialisation soon found Bradshaw touring the world with big-name artists: Olivia Newton-John in ’82, Joni Mitchell in ’83, Toto in ’85 and over the years, he’s either built rigs for, or toured with, Michael Landau, Steve Lukather, Steve Stevens, Edward Van Halen, The Edge, Warren Haynes, Billie Joe Armstrong, Trey Anastasio, J Mascis, Kirk Hammett, Marty Friedman, Michael Schenker, Mick Mars, Prince, Peter Frampton, Nikki Sixx, Tom DeLonge, Yngwie Malmsteen, Vivan Campbell… and the list goes on, and on and on.

Yet because he was working in the environs of Los Angeles, the high-end outboard of the city’s big studio scene would soon creep into the pedal-based venture – and things would change dramatically.

Rack it up

“I’m based in Los Angeles,” says Bradshaw, “and what is in Los Angeles? Studios! So I was working for studio guys primarily, in the beginning. They’d come in and say, ‘I want to use this Eventide Harmonizer…’ It was meant for studio use, and the early H910 Harmonizers or the H949s and stuff, they were 100 per cent wet, there wasn’t any control for mixing direct sound with those things. They were made to be used in a mix buss, so there was no dry signal passing through them.

“And keep in mind, in the beginning, all of the effects chains were right into the front end of the amp and there was no such thing as preamps or effects loops, none of that stuff, when I started. I had to build what I called a Harmonizer interface, which gave you level controls and mix controls, so that you could then blend in how much of the effect you wanted.”

Bradshaw’s first major client was Buzz Feiten, for whom he adapted 19-inch hi-fi cabinets to carry the rack units and switching system, with discrete pedals mounted on top, before portable, guitarist-friendly rack cases were even available. After that, he also started working with Michael Landau and a host of other major studio names, which was when it came time to crest the next major tone summit.

The bigger challenge shaping up for Bradshaw and CAE wasn’t even that of how to make these studio-intended units function adequately in a guitar rig, but how to get the full, unfettered sound of a guitar amp into the front end of the studio outboard gear, rather than vice-versa.

It’s a conundrum with which countless guitarists still wrestle today – employing buffered effects loops, post-amp reamping or attenuating boxes like the Fryette Power Station or Universal Audio OX Box, or other wet-dry solutions in the process – but when Bradshaw first tackled the issue, it was very much uncharted territory.

The reactive load

“Even before I hooked up with Steve Lukather and Eddie Van Halen and people like that,” Bradshaw recalls, “Mike Landau and I developed a lot of innovative stuff that is ubiquitous today. It’s crazy the stuff we came up with! But before that, it was always effects hitting the front end of the amp.

“So, what happens? When you’ve got a high-gain amp and an echo, the echo repeats don’t hit the front end of the amp as hard, so the echo repeats die off sounding thinner than the initial note. So, we were like, ‘W-w-what? Why? What’s going on here?’

“So I thought, ‘Let’s try this…’ We’ll try using an amp as a preamp and then put the effects after it, so that means we’ve got to pad down an amp signal – and I wanted to use the whole sound of the amp, too, because I wanted it to be just like they would do in the studio, where they would mic up an amplifier and that mic signal would go to the outboard gear in the control room, and then that would get processed. And you’d hear thick effects. Like if you used flanging or anything like that in the studio, they were flanging the entire amp sound, not the guitar sound.”

The solution that Bradshaw and Landau devised was to use a large load resistor after the amp’s speaker output, and to tap a line-level signal from that which would be fed into the effects, then re-amped into any conventional power amp. Voila! The thickness of a studio-processed guitar amp was back, with the full effect of the processing unit applied to it.

While the technique worked for the high-gain Mesa/Boogie amps that were popular at the time, though, Bradshaw and Landau found it was less successful coupled to the back end of a Marshall or the like. “We noticed, ‘Marshalls sound thinner or compressed or something when we’ve got this load resistor on,’” Bradshaw recalls. “What’s going on?”

“Then one day I put a speaker on the damn thing and hid the speaker so we didn’t hear it, and listened to that, and it was like, ‘There it is!’ We’d been missing out the entire time, because the amps need to see a reactive load, you know? You need to see some push-back from the coil of the speakers and that created life in the amplifier. Now the amp’s breathing properly. But now we’re lugging around these little boxes with speakers in them, rumbling off in the corner, ha ha!”

The birth of the rack preamp

The system was working, and the tone was mighty – but it was a lot to lug around, even for touring pros with a parade of roadies at their bidding. Touring with Steve Lukather, for example, Bradshaw tells us – which he did fairly steadily from 1985 to ’92 – meant carting three amps, one for each core sound: a Soldano SLO-100 for leads, a modified Marshall for crunch and a long-box Mesa/Boogie for cleans.

“So this is a big-ass case that you’re touring around with!” he declares. “And built into this case it’s got these load boxes, too, that are rumbling away next to the amplifiers, 12-inch speakers in a box that’s sealed up, to act as the load. We weren’t going to compromise.

“So I go, ‘Man, there’s got to be a way to cut this down. These amps are being used as preamps. What if we take the preamp stages of these things and put it down to a two-rack-space box with three channels in it, one clean, one crunch, and one solo?’

“I commissioned Mike Soldano and gave him one of my switching-system chassis to put it in… Three independent channels, gain, bass, middle, treble, and master on each channel, switchable from my switching system into one output that went through the effects.”

The legendary Soldano X88R tube preamp was born. “I didn’t even tell Lukather about this,” Bradshaw recalls. “I did it on my own… He was blown away, man!”

A few years after having encouraged Soldano to run with the idea on a production level, a combination of his desire to improve upon the template and the paltry margins he was getting on installing the X88R into his own systems (“he sold those things for $1,800 a pop, and he sold them to me for $1,700 a pop – and it was my idea!”) led Bradshaw to hook up with New York-based guitar and amp tech John Suhr, who had modified one of Bradshaw’s own Marshalls to achieve some stunning sonic tricks.

Suhr designed the 3+ tube preamp, formed Custom Audio Amplifiers (CAA) to work alongside Bradshaw’s CAE manufacturing it, and moved out to LA to dive into the rack business. “We added an active tube-stage EQ at the end of the preamp,” Bradshaw explains, “so that would give bass and treble and a level control to push these flat power amps. And that gave us more tonality all the way around. The clean channel had as much level as the lead and crunch channels now.

“The clean channel on the Soldano was a little weak, it always needed help. So we fixed all those things and gave it our take on what we thought was the best-sounding preamp. Of course, Mike [Soldano] was not necessarily thrilled when we came out with this preamp, but he understood… and it was my idea in the first place. And he’s a good guy, he was cool.”

The end of an era

Ironically, it was the intended epitome of the rack-mounted effects that served, in part at least, to turn the tide back away from this format. If one decent sound in a 19-inch-wide unit was good, a plethora of sounds packed into a single rack-mounted box had to be better, right? Not so much.

“A lot of manufacturers started coming out with multi-effects and you get jazzed about it at first, but then you go, ‘No, this thing’s a pain in the ass to sit there and press a button and watch the number scroll…’ It takes time, and they might switch slowly for channel-switching or MIDI control or something. And they have 12 effects! ART had a rackmount thing that you could use 12 simultaneous effects in ’em, and most of ’em sounded like shit!”

Many discerning artists soon turned away from these outwardly versatile new tools, and while many still stuck with their single-sound units, the revival of traditional single-effect pedals throughout the 90s and into the 2000s helped to change up the rack rig further.

“I was still going with the original stuff that I used in the first place,” says Bradshaw. “The best stuff for me was stuff like Lexicon PCM70s for reverb and reverb only, or the PCM42s, one of the greatest delays ever made, so the racks were big because you had a lot of one-trick ponies in it.”

By Bradshaw’s estimation, the natural ageing of the guitarists who were using the things accounted for a big part of the rack system’s demise, too. The guys who weren’t paying someone to haul these big rigs got tired of doing it themselves as they turned 35, 40, and 45 years old or more; and for the guys who did pay cartage and freight companies, such costs “went through the roof,” in Bradshaw’s words, in the late 90s and early 2000s.

That, and the boom in old-school effects pedals, brought so many new flavours to the table that guitarists were eager to dive back into the pedalboard-based effects rigs that were the norm when Bradshaw first entered the game in the late 70s.

“You got instant gratification from a pedal,” he declares. “You turned a knob, you heard a result immediately. The other thing, too, is that rack-mounted gear often is considerably more expensive than spending $200 for a pedal. You can go out and spend $600 on a bunch of pedals and get instant gratification, whereas you’d have to save up some dough in order to buy your latest rack-mounted hoosiwhatsis. So that was a big factor, too.”

Closing the circle

Today, after moving ‘back east’ to Pennsylvania several years ago, Bradshaw finds himself having gone nearly full circle in this business. Although many of the ingredients have changed, the process and format are much the same as they were when he started.

“This business goes in cycles, you know? When I started I was dealing with Boss pedals and MXR pedals and a few rackmount things.” Now, he explains, it’s not a whole lot different, there’s just more variety. Also, these days the rack component is more often likely to be a modelling solution like those from Fractal, which Bradshaw frequently integrates with traditional pedals and tube amps.

“The Fractals are not exclusive anymore, they’re used in combination. Because they have strengths in those things, and a lot of guys will just use them for their effects. I don’t feel threatened by that stuff at all. I welcome it. Because it’s just another wrench in the toolbox, man, that a musician has at their disposal.”

More information at customaudioelectronics.com.