Related Tags

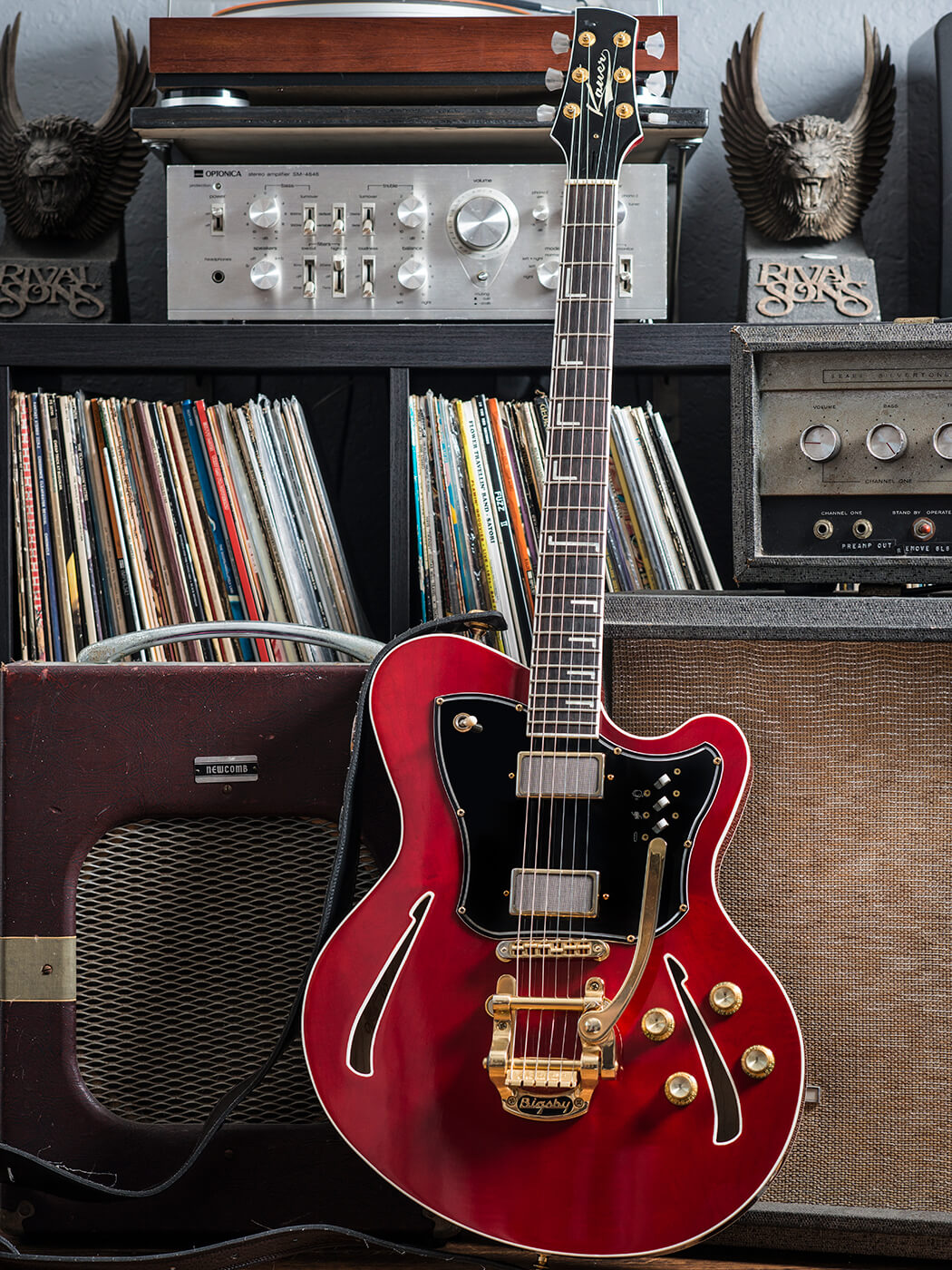

Talking Shop: Doug Kauer on automation and alternative tonewoods

In an industry that celebrates hand-built everything, it’s refreshing to hear a guitar maker openly declare that certain forms of automation just create better guitars. Doug Kauer celebrates the power of machines, while still valuing the creativity of human hands.

Image: Scott Beckner

Likely it’s the customers plying the waters of the boutique-guitar market who have romanticised the concept of ‘hand-made’ more than the makers themselves. Bodies and necks must be hand carved, pickups hand wound, finishes sprayed by hand. Yet, get some of the makers themselves to speak candidly, and many will admit to superior and more consistent results when you let automation play its part. Doug Kauer, head of California-based Kauer Guitars and a luthier with a growing reputation in the industry, is vehemently one of them.

“There’s that question of, ‘how can we take this to a level that the hand simply cannot match?’” Kauer posits. “And that’s what just blows my mind. The CNC is a legitimate tool that opens up all kinds of possibilities we didn’t have before, and then the Plek machine is the esoteric next level. We’ve been taking guitars that I thought were the pinnacle of my thousand-guitars-fret-job experience now, and that were the best-playing guitars I’ve ever done, and you put them on the Plek and realise they’re good, but they’re going to come out noticeably better.

“And it’s amazing to see how many cottage industries have sprung up from people who are taking advantage of – and this is going to sound very bourgeois – the democratisation of technology,” he adds, “using CNC machines, cad-cam software that’s more available, and stuff like that.”

Ex machina

“Stuff like that” seems to come entirely naturally to Kauer, likely because it’s in the blood, thanks to a dad who devoted much of his career to precursors of such machines, and the work done with them. Kauer was born in Elk Grove, California, in 1983, after his parents had moved to the then-quiet town just south of Sacramento to escape the rising cost of living in the San Francisco Bay Area.

“My dad got into woodworking as a hobby,” he tells us, “and he mostly got into restoring these things called Shopsmiths. They’re like a Swiss Army drill-press, I don��’t know how else to describe it – kind of an all-in-one, variable-speed drill press that you could lay flat and use horizontally. There was a table-saw attachment, a sander… most of the stuff was absolutely terrifying, oh my god [laughs], but as a drill press goes it’s a fantastic machine. We have a bunch of them here at the shop. But he got into restoring those things, and then got into making cabinets and furniture, and that evolved into having his first shop.”

When Doug Kauer was five years old, his father left his day job to set up his own shop doing cabinetry full time, and the family business paved the way for a lifetime of learning for junior. As he puts it, “The running joke has always been that child labour laws only apply to everybody else’s kids [laughs]. I got stuck working at the shop my whole life.” Little did he know then, of course, that such work would eventually become his life.

As his formal schooling progressed outside the shop, Kauer eventually began working to complete his teaching credential, and still declares a love for the classroom. Even his experiences in the California state school system, though, seemed to be steering him back to the wood shop.

“I took CAD [computer aided design] my senior year of high school because it counted as a math class,” says Kauer, “even before we got the CNC. Then around 2000 dad’s shop was the first cabinet shop in the Sacramento area to have a CNC machine. Then this piece of maple came into the shop – dad had ordered a bunch to make crown molding or whatever he was doing – and it was really a nice piece. Dad played guitar too, and I’d made a lot of furniture over the years as a kind of side income, and I saw that piece of maple and thought, ‘You know, I kind of want to build a guitar.’

“At the time, I didn’t know there was a boutique industry,” he continues. “I played guitar and always tinkered with mine, but I kind of had this weird epiphany of, you know, guitars weren’t actually made by some dude on the mountain top, a gift from the heavens that only a chosen few could make these things. You know, it’s wood, metal, and strings, and almost anybody can learn to do it. It wasn’t some mythical art.”

Band of brothers

The truth is, Kauer never really intended to get into guitar making at all. He used the resources in the wood shop to make one, then another, and another, learning from his mistakes each time and improving upon the next effort. When the recession hit in 2008, however, just six months after he and his wife, Theresa, had bought a house, he went back to work full-time at his dad’s shop, while Theresa pressed forward with her teaching qualification. Then, as cabinetry work slowed in the trough of the recession, guitar making stepped in as a means of filling the downtime, and bringing in a little income.

Running standard bodies for friends’ projects segued into building ground-up Firebird copies (more of which later), then segued into an original design: the Daylighter.

“I designed the Daylighter as kind of a Jazzmaster-meets-Les Paul mashup,” Kauer explains. “Two humbuckers, Gibson scale, set neck, that kind of thing, and that just happened to be right place, right time, I guess. People started bumping me for them. I was like, ‘I don’t know if this is really what I want to do. I don’t know if I want to ruin another hobby of mine!’ [laughs], which I had decidedly done once before and was real apprehensive about doing it again. But people started asking, and there wasn’t a lot else to do.

“It sounds like such a terrible way to get into it! So, I started getting more serious, and that’s when I started finding out that there was a boutique industry. I went to NAMM with a friend, and another friend told me I should introduce myself to Nik Huber and Juha Ruokangas and a few other guys, so we walked the show every day and I stopped and talked to Nik the first day, and I remember thinking, ‘God, those things are four grand and they’re all sold on the first day!’ Honestly, I wish I could have gone back in time and bought all of them, because Nik’s guitars are, what, about ten grand now, average?

“And that same year in July I went and did the Montreal Guitar Show, which was my first real guitar show as a builder, and I was maybe on guitar 40 or 50 at that point. I walked into the show to set up, and Nik was there, and he remembered exactly who I was, and was like, ‘Oh, man, I’m so happy you’re here! I’ve been following along seeing what you’re doing online. I’m really excited things are going well for you!’ And I walked away from that thinking, ‘What industry would this happen in? That’s insane!’

“I had a lot of fun at that show – I think everyone in Montreal knows that I had too much fun there – but I sold a guitar, everybody was super supportive, I made friends that I talk with frequently to this day. And I came home and quit my job. I wanted to go full-time into this. There were the people I’d fallen in love with, and almost secondary was the idea of selling guitars to people.”

Wailing banshee

In addition to his original Daylighter model gaining a head of steam on the market, Kauer found a surprising number of guitarists remembering his early efforts at the Firebird format, and coming back to him for reverse ’birds of their own. It was something he’d avoided making for the first few years of the business – as Kauer puts it, “I was very happy to get our cease-and-desist order!” – but few fledgling guitar makers can afford to turn down work, and he begrudgingly heeded the call.

“I have kind of a love-hate relationship with Banshee,” Kauer says of the reverse-bodied model that has evolved from his early shots at the Firebird. “I mean, I love that guitar, and the current version is a different thing, but the original, yeah, it was a Firebird copy, and I just didn’t want to be ‘that guy’. I wanted to stand on the merits of my own designs. But I had made some improvements that people caught wind of pretty quickly, and we kind of gained a reputation for making the best version of that guitar.”

Since the early years of Banshee production, given the differences between that model and the original Firebird, Kauer and Gibson have come to an agreement allowing him to continue production of his own reverse-bodied through-neck guitar. For the most part, though, Kauer is more satisfied when working on his own original designs, threading that needle of trying to devise lines and stylings and feature sets that represent something new, but which aren’t so unfamiliar that they repel guitarists.

“I wouldn’t say that we’re groundbreakingly original,” he says, “not by any stretch, but I knew the little niche for something that I wanted to do, and was dumb enough to get started with it and stubborn enough to stick with it, and eventually people caught on to it.”

The trick is, while design efforts are one of his favorite aspects of the business as a whole, when business is good there’s little time to get himself back to the drawing board. And when business is slow, it’s all-hands-on-deck trying to drum up new customers to keep both himself and a company that has grown to include five other employees, well, fully employed, with little time left for design work then either.

“We did Daylighter in some variation for nine or 10 years, and it’ll come back at some point,” says Kauer. “Then I came up with Starliner, and I really love Starliner right now. I think that’s what helps keep us going. I always feel bad for… I mean, I don’t feel that bad for the Rolling Stones, but I have to imagine that playing Brown Sugar for the millionth time must kind of suck, but when you’re making enough to buy an island it offsets that pain.

“I just kind of want to keep doing things that make me excited to come to work. I get – I call it ‘slow-forming ADD’ – and outside of Banshee most of what we make will have about a three or four-year lifespan, and then I want to make something new. And I will never get rid of Super Chief either. That is everything from 12 or 13 years of doing this, all accumulated into one guitar.”

Alternative tonewoods

Kauer’s modest quest for originality covers not only aspects of his guitars’ overall designs, but he’s also an enthusiastic embracer of new materials and components that might fall outside the internet forum ‘flavour of the month’ ingredients that divert many guitarists’ expectations, and frustrate so many builders in the process.

“We were early adopters of a couple of things,” he relates. “Juha Ruokangas turned me on to Spanish cedar, which we call Spanish mahogany because it’s not cedar and it’s not Spanish, it’s a mahogany variant, so we took the liberty of renaming it. That was a great bit of advice. It’s 99 per cent of what the Kauer sound is. It so specifically checked all the boxes I wanted out of a wood. It sounds great, the weight’s great, everything about it’s really good. So that was an early-on thing for us.

“Then we also went through the gamut of different fretboard woods, and early on we did a guitar with a wenge fretboard. I hadn’t heard of wenge at the time, and I ended up falling in love with it. I really like that it isn’t environmentally impacted like so many of the rosewoods were. We switched permanently to that within the first year of Kauer as a business, and that really paid dividends, especially in the last few years.

“It’s tough, because both Spanish cedar and wenge weren’t the rubber-stamped formula that everybody knows, and it took a little while for people to be willing to trust my word that it was great. Then when the rosewood restrictions happened and everybody had to kind of face reality, especially with wenge, that there are tons of other great woods out there that aren’t so impacted.”

Talk of fretboards also gets us into another Kauer departure from the popular line on tonewoods and their supposed impact on a guitar’s overall sound – namely, the significance, or relative lack thereof, of this thin slice of timber in the final brew.

“Frankly,” says Kauer, “I think fretboard wood choice is way overblown. I’m in that camp that if you want to drastically change what a guitar sounds like, changing what the neck is made from and how it’s made, I’ve found experience-wise, is a much different equation. But as much as people over-hype what the fretboard wood is, I don’t find much difference in the sound of fretboards. We pick fretboards for stability and sustainability first, and then how it machines and how it holds a fret, and then how it looks. The lowest of the low is what it sounds like, because it’s a one-percent difference, at best.”

Finished product

Where a lot of guitarists and makers alike will also rail against finishing processes that deviate from the ‘best practices’, this is another area where Kauer is willing to take a results-led approach, and to trust the empirical evidence. As with wood choices, there are sound environmental reasons for reconsidering the supposed supremacy of nitrocellulose lacquer; and as for any objective assessment of the results, Kauer says there are reasons there, too, to seriously consider the alternatives.

“We’re in California, and I have restrictions about spraying lacquer in the first place,” Kauer says, “and we quickly surpassed the amount that we could get away with spraying legally. I switched to [poly]urethane, and I was so nervous about doing it. I didn’t talk about our finishes for a while because I was so anxious that people were going to be like, ‘Oh, it’s not nitro, it can’t be good!’ I’ve never heard any difference between those guitars, and I’ve had plenty of examples on both sides.

“And the UV finishing made a monumental difference in the quality of our finish,” he adds, “not to mention the turn-around time, but the quality just went through the roof. And that’s kind of when I just stopped worrying about that stuff. There are so many individual components and pieces and steps and techniques, and I’m happy with the sum. I’m not totally hung up on how we got there.”

Visit kauerguitars.com for more.