Related Tags

Space & Time: The birth of reverb, delay and other good vibrations

Continuing his guided tour through the early days of effects, this month JHS Pedals main man Josh Scott is floating in space, and nobody can hear him do much of anything.

Image: The Print Collector / Getty Images

Last time out, we spoke about Mark Twain’s love of guitars, and continued our journey through the early days of effected guitar with a look at the very first guitar effect: tremolo. This time, we’re going to explore the two other pillars of those early experiments in guitar effects, which remain hugely important to us today – delay and reverb.

I first experienced the effect of delay the way a lot of us did: as a simple echo. I vividly remember yelling across an empty parking lot and hearing my voice bounce off a brick wall and fly back at me. I was 10 years old, and this was more entertaining than any game on my Atari. Learning that my voice could bounce off the wall like a kickball, and that somehow, a parking lot and a brick wall could duplicate sound? It was pure magic.

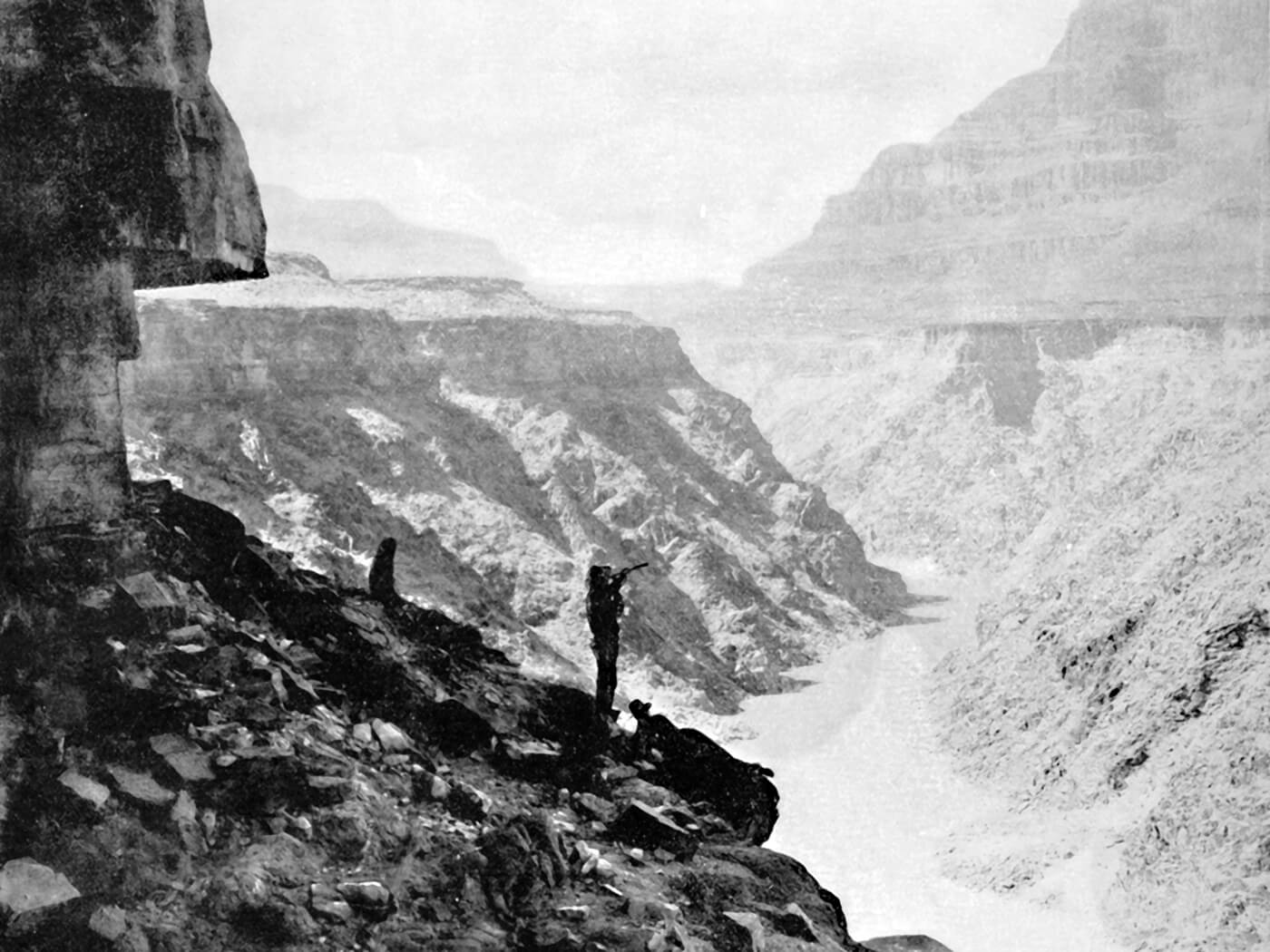

I imagine musicians throughout history sharing this experience. A cowboy strumming his campfire songs in the base of a canyon. A classical guitarist performing in a Spanish chapel. A caveman shouting his love song into an empty cavern. Delay was first a natural effect, produced purely by the physical space that you found yourself in.

Tinker, tailor…

In the late 40s and 50s, a young guitarist, tinkerer and brilliant engineer named Les Paul wanted to artificially replicate the sound of these bigger spaces. He longed for his home studio recordings to have the big, open room sounds of a professional studio space. As usual, necessity became the mother of invention.

Some of you may only know Les Paul as the name on your favourite guitar’s headstock, but Les actually wore a lot of different hats: he was an inventor, an amazing guitar player and a recording engineer. Les Paul played a pivotal role in the invention of the solidbody electric guitar. In his day, Les and his musical partner Mary Ford (who was arguably the better guitar player) were kinda like an Andy Griffith Show version of Beyoncé and Jay-Z. With Les’s inventions, an amazing live act and massive radio hits (not to mention their hit TV series) they successfully made the electric guitar a common household appliance just like a vacuum cleaner.

Les would link his big reel-to-reel recording units together, creating a Frankenstein’s monster of audio manipulation, and in doing so, he manually created the sound of fake space he wanted in his recordings. He would record audio onto one tape, and simultaneously have another machine that played the recorded part back on top of the live sound in real time. So you hit a note, twang, it would go into the recording unit to be recorded, play through the playback unit, and be mixed into the live performance, slightly offset so it was ‘delayed’: twang, twang. Thus, artificial echo was created.

In 1953, a music store owner from Illinois named Ray Butts created a device he called the EchoSonic. After hearing Les Paul’s slap delay effect and realising how hard it was to recreate outside a studio, he wanted to see if he could simplify this for everyday musicians. He created a combo amplifier with a built-in tape echo machine that was easily accessible and operational.

The EchoSonic became a huge success when Nashville studio legend Chet Atkins adopted it, influencing guitarists like Scotty Moore and rockabilly superstar Carl Perkins to do the same. Both men’s guitar sounds played huge roles in developing Sam Phillips’ Memphis Sun Studios sound, launching artists like Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash into worldwide fame.

Over the next few years, standalone tape echo units would enter the market all across the world, and delay’s popularity further exploded through the 60s and 70s, becoming a staple effect of the electric guitar. Les Paul’s experiments in replicating the sound of bigger space in his home studio resulted in iconic guitar tones like Elvis Presley’s Mystery Train, Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love, Pink Floyd‘s One Of These Days and countless others.

Tank commander

A few years ago while visiting the BOSS headquarters in Hamamatsu, Japan, I found myself in a room called an anechoic chamber. A giant insulated door swung open, and my wife and I walked through it onto a floor made of large rope-like netting. We were floating in midair above a huge, open and completely soundproof pit. Above us, below us and all around was a perfectly-designed sound treatment that had one purpose: to stop all sound.

The door we had walked through suddenly closed, and something crazy happened: for the first time in my life I didn’t hear any reflections. No natural reverb. At all. This chamber was completely immune to moving soundwaves. Basically, any sound we made died almost as quickly as it was created. As I spoke, I could hear everything inside my head, I could feel and hear sound before it left my mouth, but it didn’t resound at all.

Even in the name of science, it was a super creepy experience. A recent article by Smithsonian Magazine reported that the longest anyone has been able to stay in an anechoic chamber is 45 minutes. My wife and I lasted about five minutes. If I’d stayed in that room much longer, I would have definitely hallucinated Agent Smith from The Matrix saying, “What good is a phone call if you’re unable to speak?”

Until I had this (admittedly strange) experience, I’d never realised that in every moment of our lives, we are constantly hearing reflections and that those reflections create our understanding of depth, space and distance. Think of it as human echolocation. Imagine it: sound waves bouncing like lasers between walls, pictures, floors, coffee mugs, computers; these reflections give every room some form of special identity. Try it out for yourself. Clap, yell, scream. Scare your neighbours – they can handle it. While delay is a straight line of reflection with its length determined by how far away the reflection turns around and starts back to you (the brick wall and the parking lot), reverb is the sound of thousands of reflections crashing in on you from different angles and distances. If delay is a dripping faucet, reverb is Niagara Falls.

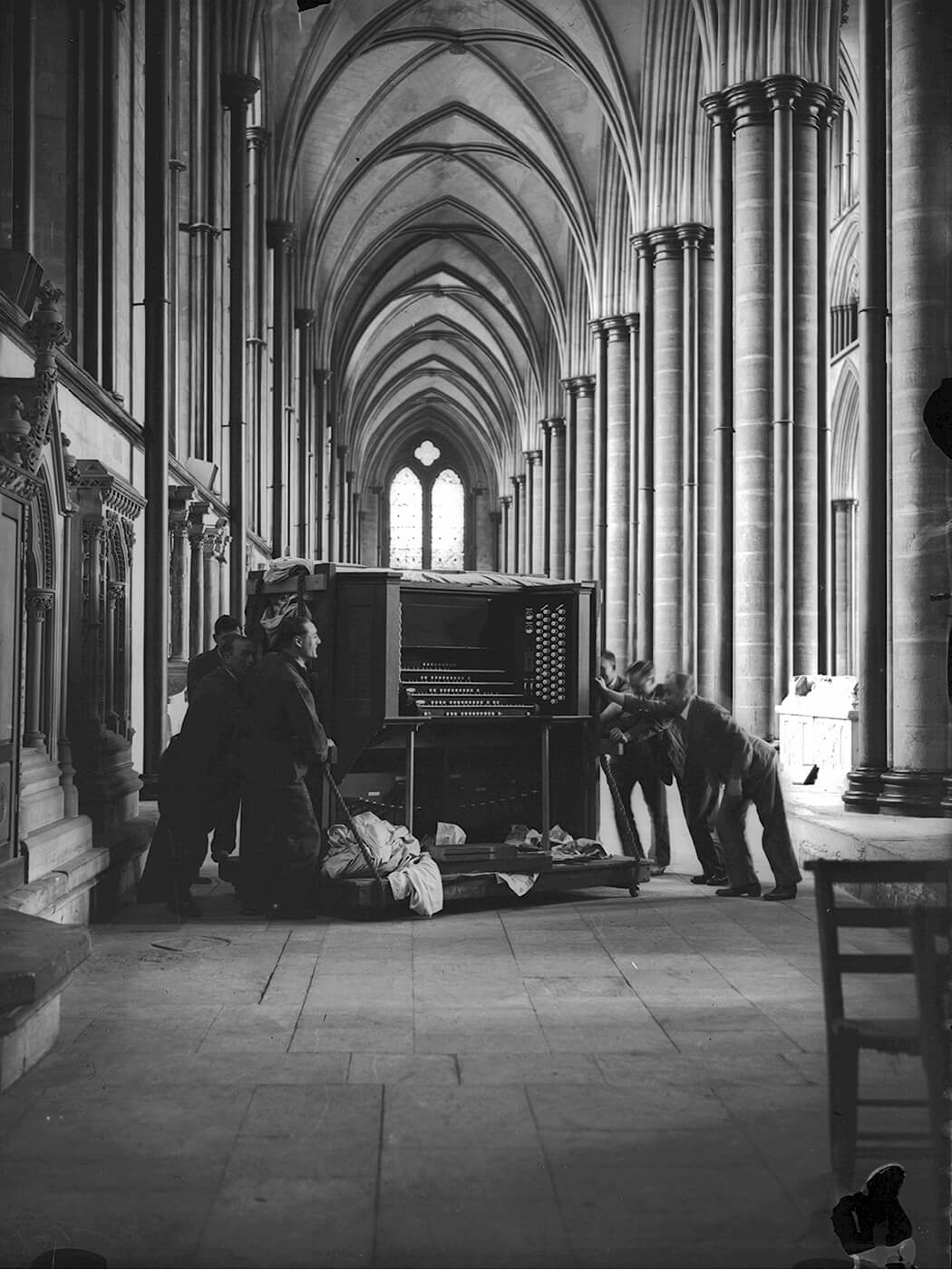

In 1939, Laurens Hammond patented a new creation he called ‘spring reverb’. He had a peculiar problem and he found his solution in a modified Bell Labs invention, originally designed to replicate the delay in long distance phone calls. Hammond made organs, so churches were his primary customer base. Small churches would buy his organs and comment on how they did not sound as “good” as the big pipe organs in a cathedral. Laurens understood that the problem was not his electric organs, it was the space they were being used in.

If you have ever been to a cathedral and heard a pipe organ in person, you know that it’s an otherworldly, crazy, huge sound. The church itself is actually part of the instrument, and its signature sound comes from the reflecting sound waves that bounce across the massive, vaulted ceilings and hard walls and floors. Basically, a pipe organ takes on the sound of the building it’s housed in, and it’s a heavenly thing to experience.

Hammond used his new invention to send the sound of his electronic organ through long springs that simulated space. At one end of the spring tank is a transducer that causes movement in the springs by sending an audio signal into them. As vibrations happen and remain in the springs, lots of mechanical delays occur. A pickup located on the other end of the spring tank captures this series of delays (artificial reflections) and this is mixed back in with the clean sound of the audio input. This revolutionised the sound of the electric organ by giving its users the ability to create fake space, to make a country church sound like the Vatican.

Surf’s up

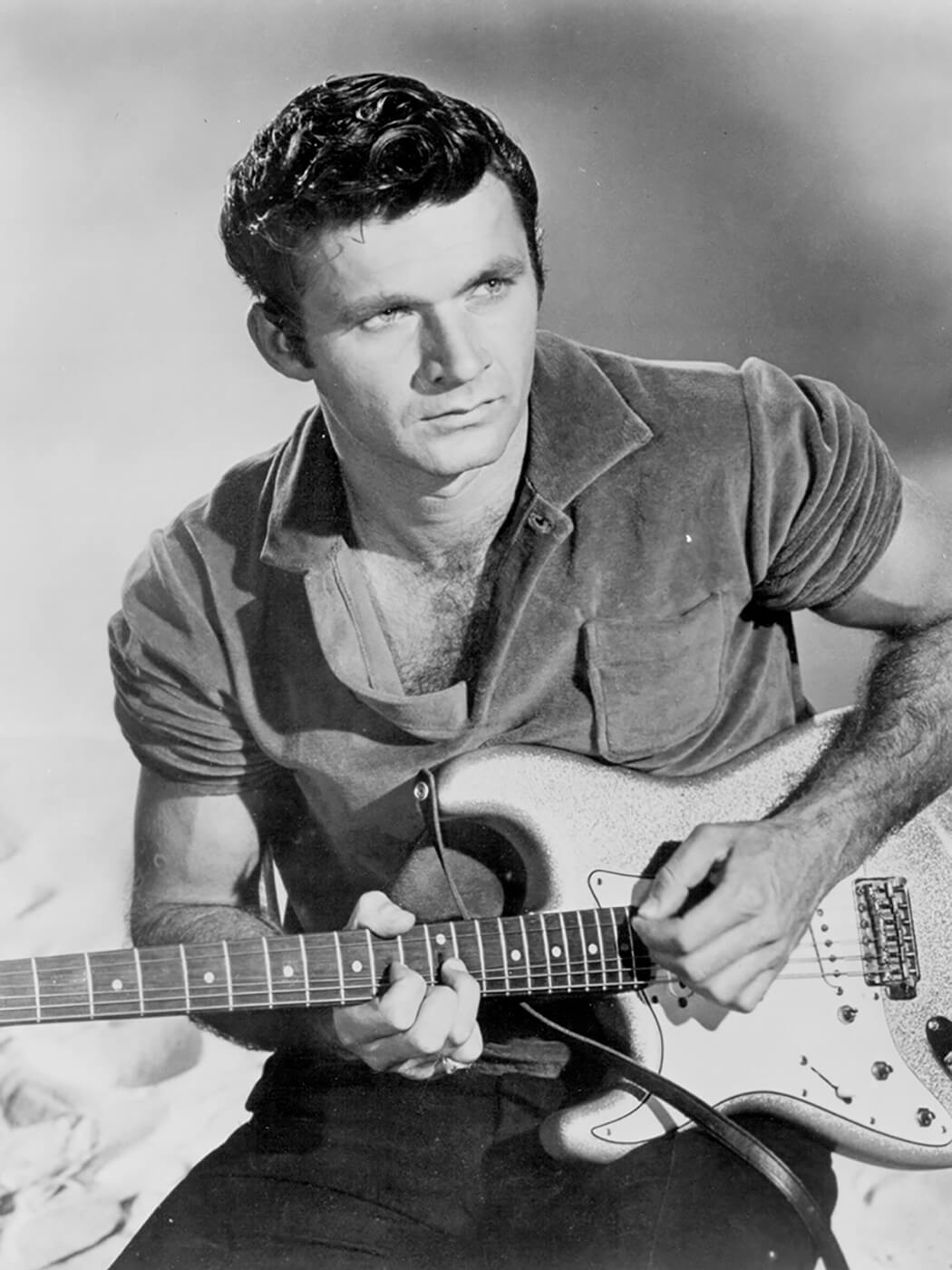

It wasn’t long before the Father of Surf Guitar himself, Dick Dale, was running his vocals and guitar through his Hammond spring reverb unit. He loved the artificial space that it created in his recordings, but couldn’t help wondering if there was an easier way to produce it for live performances. In 1961, Dale partnered with serial inventor Leo Fender to produce the world’s first stand-alone reverb unit for guitar. Leo licensed the basic circuit from Hammond and created the Fender Spring Reverb Tank.

When Dick Dale released his hit song Misirlou in 1963, it showcased the Fender Reverb Tank in a big way. Reverb made guitar larger than life and gave birth to new genres, such as surf rock and spaghetti western. You could even make a solid argument that reverb made Quentin Tarantino a legend; Pulp Fiction’s opening credits would not feel the same without Dick Dale’s thundering surf anthem pushing the beat.

It’s impossible to oversell how important these first electric guitar effects – tremolo, echo and reverb – are to music history. They are more than sounds; they are major pivots in how technology changed the sound of our culture. These inventors put electric guitar on an entirely new course, not just to be louder but to be an entirely new instrument. Basically, Harry DeArmond, Les Paul, and Leo Fender didn’t just give guitar a new voice, they gave it a new language as well.

Join Josh Scott for more effects adventures at thejhsshow.com.