Related Tags

Why Kraftwerk and Florian Schneider matter to all guitarists – no, really

In subtle ways, Kraftwerk’s groundbreaking synthpop wormed its way into guitar culture and tastes. With the passing of Florian Schneider, is it finally time to accept that the German band can be as important as Howlin’ Wolf in your playlist?

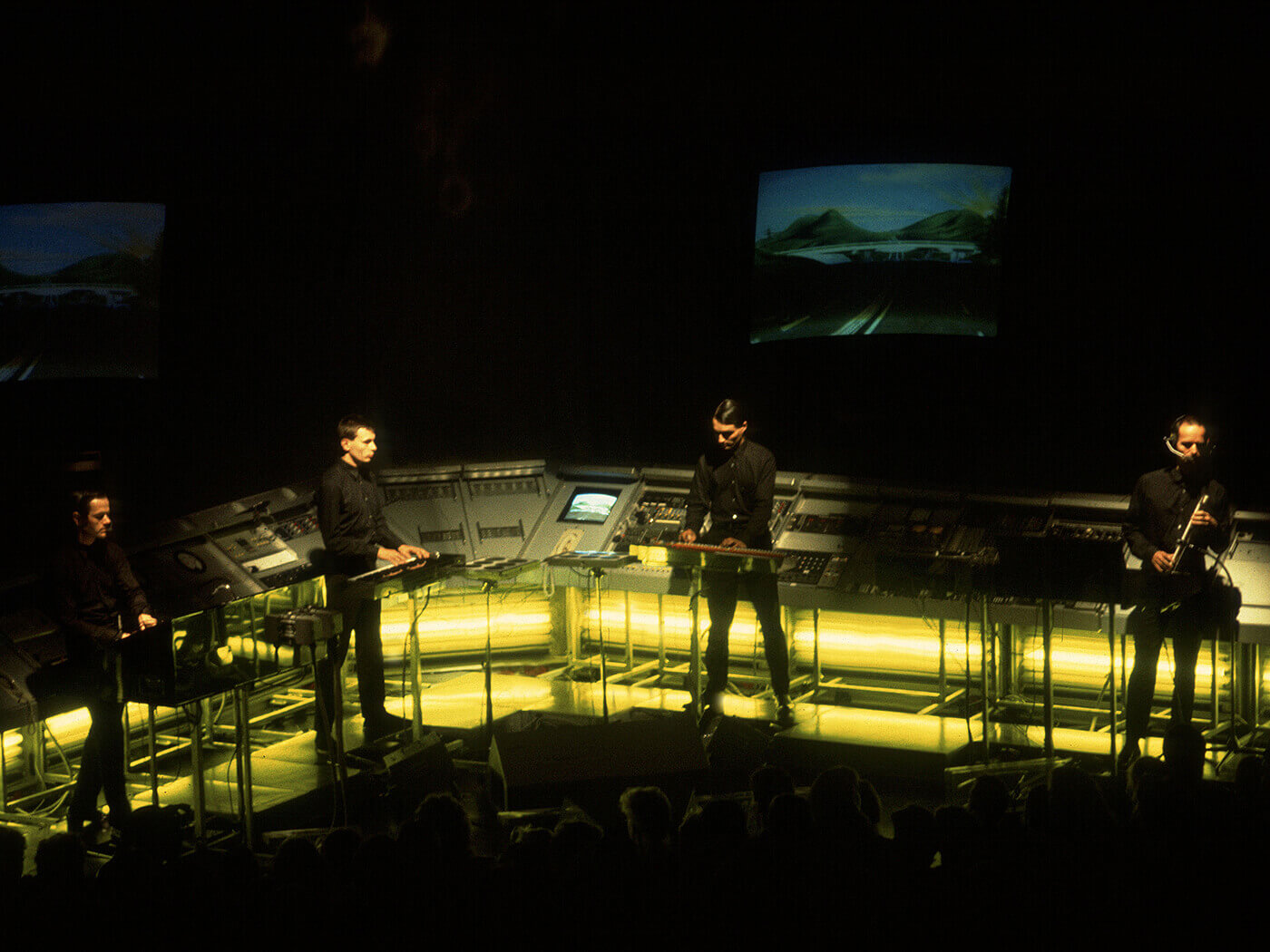

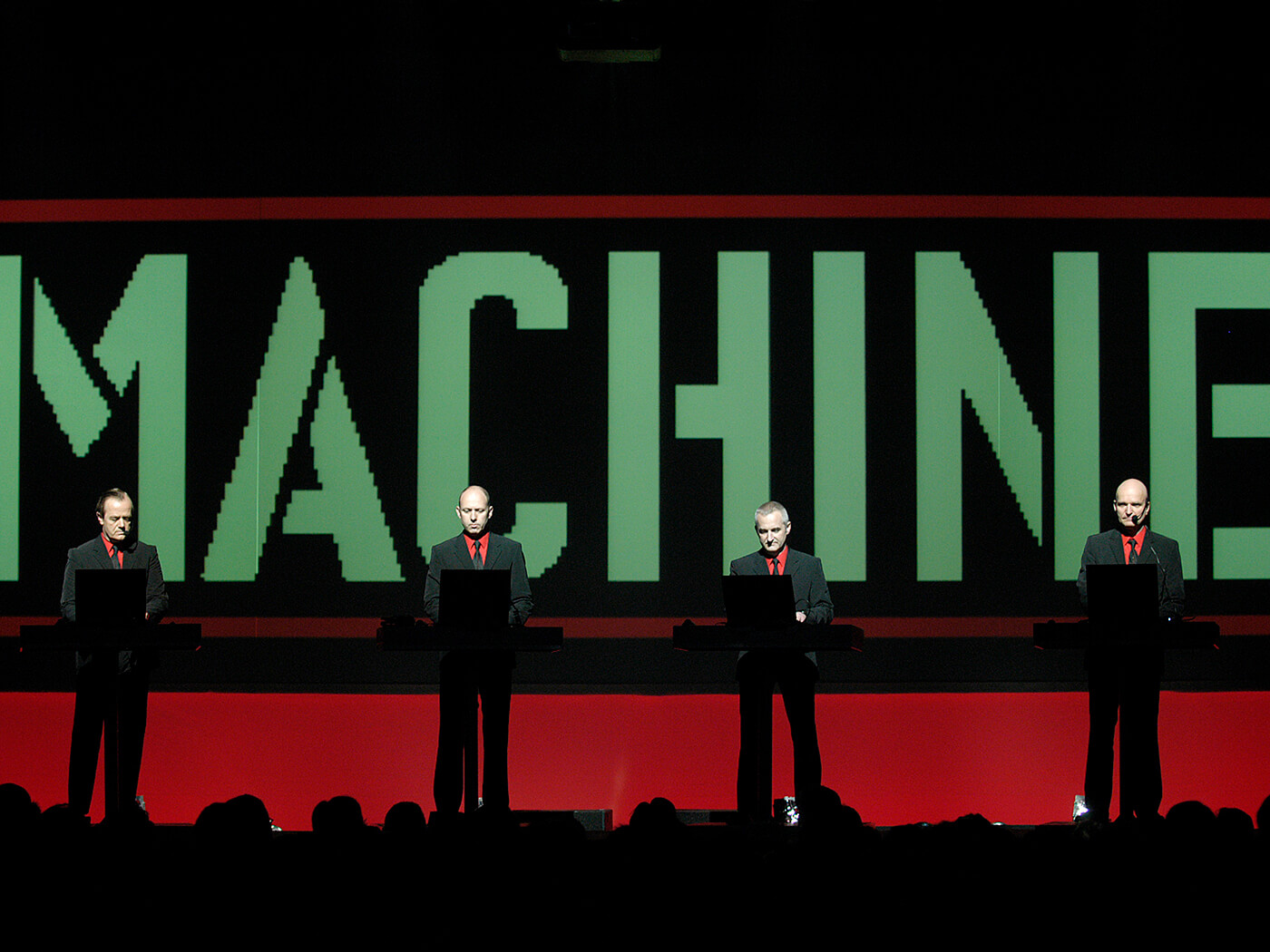

Kraftwerk in front of world time clock in Keio Plaza Hotel, Tokyo, September 1981. Image: Koh Hasebe/Shinko Music / Getty Images

The passing of Florian Schneider was a very sad day for music. Even guitarists. “Really?” you may wonder, thinking the Kraftwerk enigma had little to do with your art, but influence doesn’t always work in such linear ways. Kraftwerk’s music isn’t just a straight line from Autobahn to auto-tune… it’s woven into the fabric of modern music.

Even though Schneider officially left Kraftwerk in 2008, and the ‘brand’ continued without him (with Ralf Hütter as sole remaining original), he was always the most enigmatic and emblematic member. In the early, early 70s at Kraftwerk’s birth, Hütter still resembled a prog hippy. It was Schneider who soon brought the somewhat-comically austere look of suits and ties and neat office haircuts.

What did he ‘do’ in Kraftwerk? They were so secretive that no-one ever really knew what specifics any of them were responsible for. But, given that Kraftwerk have not released new material since Schneider departed, one can assume he had an ear for melody. And with his far-away gaze and sometimes wry smile, Schneider was perhaps the most ‘human’ of these ‘man machines’.

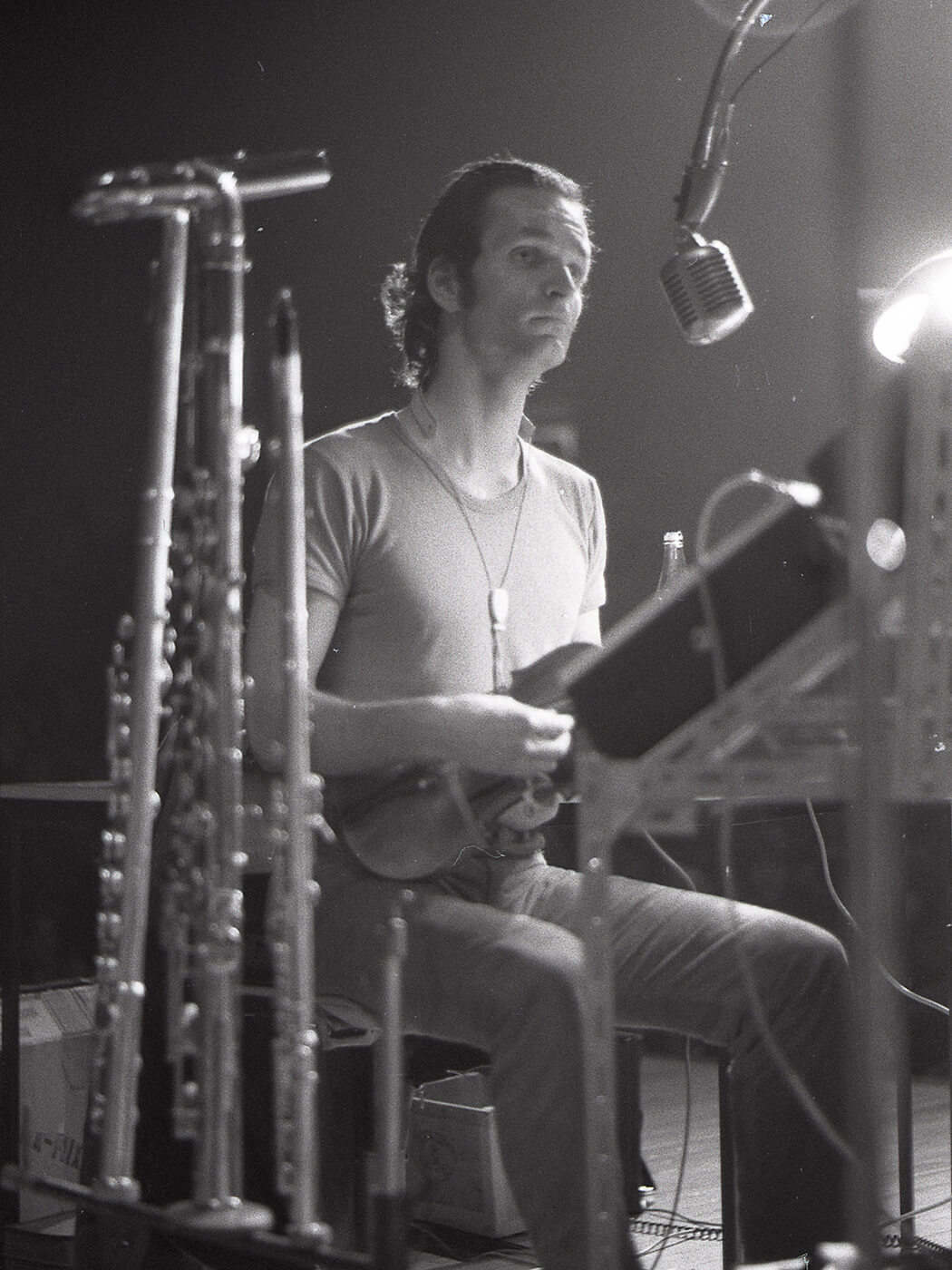

He’d actually started as a flautist, guitarist and a violinist. He was no underclass rock ’n’ roll street urchin, though. His well-heeled father, Paul Schneider-Esbelen, was a noted architect who designed Cologne’s airport. The young Florian rebelled by getting involved in an experimental band, excellently called Pissoff. He joined with Ralf Hütter to form The Organization (humourists might regard it as a more Teutonic take on ‘The Band’) before they settled on Kraftwerk (literally Power Plant) in 1970.

It is perhaps strange to see Guitar.com saluting a band such as Kraftwerk, but the Germans’ influence went beyond their peers. Maybe because they didn’t really have any obvious peers. It’s true that other early electronic bands, notably Tangerine Dream, operated in a similar realm, Kraftwerk’s aesthetic was – at the time – truly unique for a ‘pop band’.

Autobahn emerged in 1974 sounding very otherwordly (Tangerine Dream, meanwhile were more trippy and proggy). It appealed to punks in many ways. No, there were no raging guitars – there were no guitars at all – but it arguably had the same goal: dismantling hoary rock music. A slew of punk and post-punk guitarists saw appeal in what Kraftwerk were doing. They couldn’t compete with the virtuoso-wizardry of prog-rockers’ fingers or complex folk fingerstylists, but they wanted to make noise.

There was no discernable aural imprint of Kraftwerk in punk, but there certainly was in the new wave that followed. Ever since Bowie had name-checked Kraftwerk on ‘Heroes’ (in the form of the largely instrumental V-2 Schneider), the Germans became part of the ‘set text’ of references, alongside Bowie himself, Roxy Music, early disco, The Velvet Underground and others.

The early synth-pop stylists of the new wave (Ultravox, Human League) sometimes echoed Kraftwerk wholesale, but their sound also hovered around the ‘guitar bands’ too. Simple Minds’ superb Empires And Dance (1980) was neither a guitar nor synth album – it was both – but tracks such as I Travel and This Fear Of Gods nodded to the new Europeans, as did later tracks In Trance As Mission and Theme For Great Cities. With FX flourishing as part of guitarists’ palettes, some of the sounds Charlie Burchill coaxed were very synth-like, and his icy circular melodies owed little to blues rock. They sounded like Kraftwerk on guitar.

Joy Division, and the following New Order, admitted a huge debt to Kraftwerk. Bassist Peter Hook recently told the NME, “[Ian Curtis] gave me Autobahn and then later Trans Europe Express. I was absolutely mesmerised by both. Ian suggested that every time Joy Division go on stage, we should do so to Trans Europe Express. We did that from our first show, until nearly our last.

“Joy Division were very tied to Kraftwerk, but it wasn’t until we got to New Order and were able to afford the toys that our primary source of inspiration became, ‘Let’s rip off Kraftwerk’. Their music was beguilingly simple, but impossible to replicate.”

It wasn’t just the music, either. Hooky continues, “When everyone was trying to turn us into ‘Ian Curtis And Joy Division’, he would say, ‘No no, we need to be like Kraftwerk – it’s all of us, together’. That was the image that I bought into. I still don’t know which of them did what. I think there’s a strength, an honesty and a respect in that.”

A young David Evans, The Edge of U2, was (and remains) a fan. “Blues rock was anathema to me,” he told Guitar.com of his formative years, and Kraftwerk’s strict, linear melodies made total sense. No double-stops needed. Just clear, bell-like tones and a tune. It’s noticeable that the first U2 album where The Edge has a production credit is Zooropa, the band’s ‘European’, mechanistic diversion of 1993 that led off with the Kraftwerkian single Numb (written and ‘narrated’ by Edge himself). The lyrics for Zooropa (the song) open with “Vorsprung durch technik”.

We are the robot guitars?

The late 70s and early 80s saw synths become a standard part of many a band, and also the development of guitar synths (for those still seeking more familiar tactile territory). Cost and latency problems meant the likes of Roland’s GR-300 to 700 never really took off, but trailblazers embraced them. Andy Summers, Pat Metheny and even Jimmy Page (on his soundtrack to Death Wish II) were very keen.

The results didn’t always much sound anything like Kraftwerk, but there were exceptions: grab a listen to I Advanced Masked by Andy Summers and Robert Fripp (1982) and you’ll find the sensibilities of Kraftwerk to the fore, from repetitive, circular melodies, to electronic beats and mechanistic poly-rhythms. If someone said: “there’s no guitar on this”, you wouldn’t necessarily disbelieve them.

As time went on, and the lines blurred between ‘electronic music’ and ‘rock music’, Kraftwerk became just another reference point. As part of Electronic with New Order’s Bernard Sumner, Johnny Marr experienced something of a coup, though, when the duo persuaded Kraftwerk’s Karl Bartos to decamp to Manchester to produce their second album Raise The Pressure (1996).

This was a rare ‘outside’ project for a ‘Werker, though it didn’t work as predicted. Electronic was always a strange (if periodically brilliant) outfit: starting as a Sumner solo album idea, it flourished when Marr was asked to join. Bernard wanted Johnny to add his trademark six-string sounds: Marr admitted he thought it would be a great opportunity for him to learn more from Sumner about synths and programming. They were both into dance culture and music, so why not?

Recruiting Bartos, the pair hoped they might get extra “robotization” to their beats, synths and guitars melange yet, “Oddly, out of all us, it was Karl who tended to lean more towards the traditional,” Marr told Guitar.com. “He’s really into 60s pop – the Small Faces, the Kinks, stuff like that! So it was a bit strange how it turned out.” Bartos nevertheless co-wrote six of the tracks: including two of the most traditional ‘guitar pop’ ones, in singles Forbidden City and For You.

Strange indeed. Coldplay owe a lot to U2, no question. Yet it was the former who actually had more contact with the secretive Germans when they got permission to use the melody from 1981’s Computer Love on Talk (from Coldplay’s 2005 album X&Y). Rather than sample the motif, Jonny Buckland played the synth line on guitar. Chris Martin says, after writing Kraftwerk a letter asking permission, they received a handwritten reply via legal representatives containing only one word: Yes.

Coldplay bassist Guy Berryman, perhaps joking, claims Hütter “said something like, ‘Yes, you can use it, and thank you very much for asking my permission, unlike that bastard Jay-Z’.” Ha. The fact it was Hütter alone that replied is perhaps significant: although Schneider ‘officially’ left in 2009, Hütter later revealed he hadn’t really been involved “for many years.”

Over the years, Beck, The Cardigans, Lloyd Cole, Ride, Simple Minds, Rammstein and U2 have all covered Kraftwerk tunes. Industrial bands such as Nine Inch Nails absorb the electronica that Kraftwerk pioneered as much as they do the grinding riffs of metal. It’s all just a melting pot now.

It would be wrong to say Kraftwerk were responsible for everything that followed, as some fervent fans tend to overstate: their influence on techno and house is undeniable, but just because Matt Bellamy slams a Korg KAOSS pad into his signature Manson guitar, it doesn’t mean Florian Schneider is sitting somewhere, nodding like an approving guru. But Kraftwerk are around. They have been for five decades. They meant a lot, to a lot of musicians, of all tastes and flavours.

“Spineless, emotionless… keep the robots out of music,” read an early Melody Maker review. Some Gibson customers seemed to think exactly that of recent years’ “robot tuners” but, hey, many guitarists remain just immune to change or the possibilities of the new.

When once asked exactly what Florian Schneider did in Kraftwerk, the more vocal Ralf Hütter demurred to be totally forthcoming, just as you’d expect. He eventually settled on saying Schneider was a “sound fetishist”. But of course. Isn’t that what every musician is?

Read more features here.