Why do some guitars have f-holes? What is it for and why does it look like that?

Where did the concept of f-shaped soundholes come from and what does it actually do to your guitar’s sound?

If you’ve ever watched and orchestra or a string quartet play, you’ll probably have guessed that the f-hole did not originate with the electric guitar, but from the violin family of instruments that long predate the modern six-string guitar.

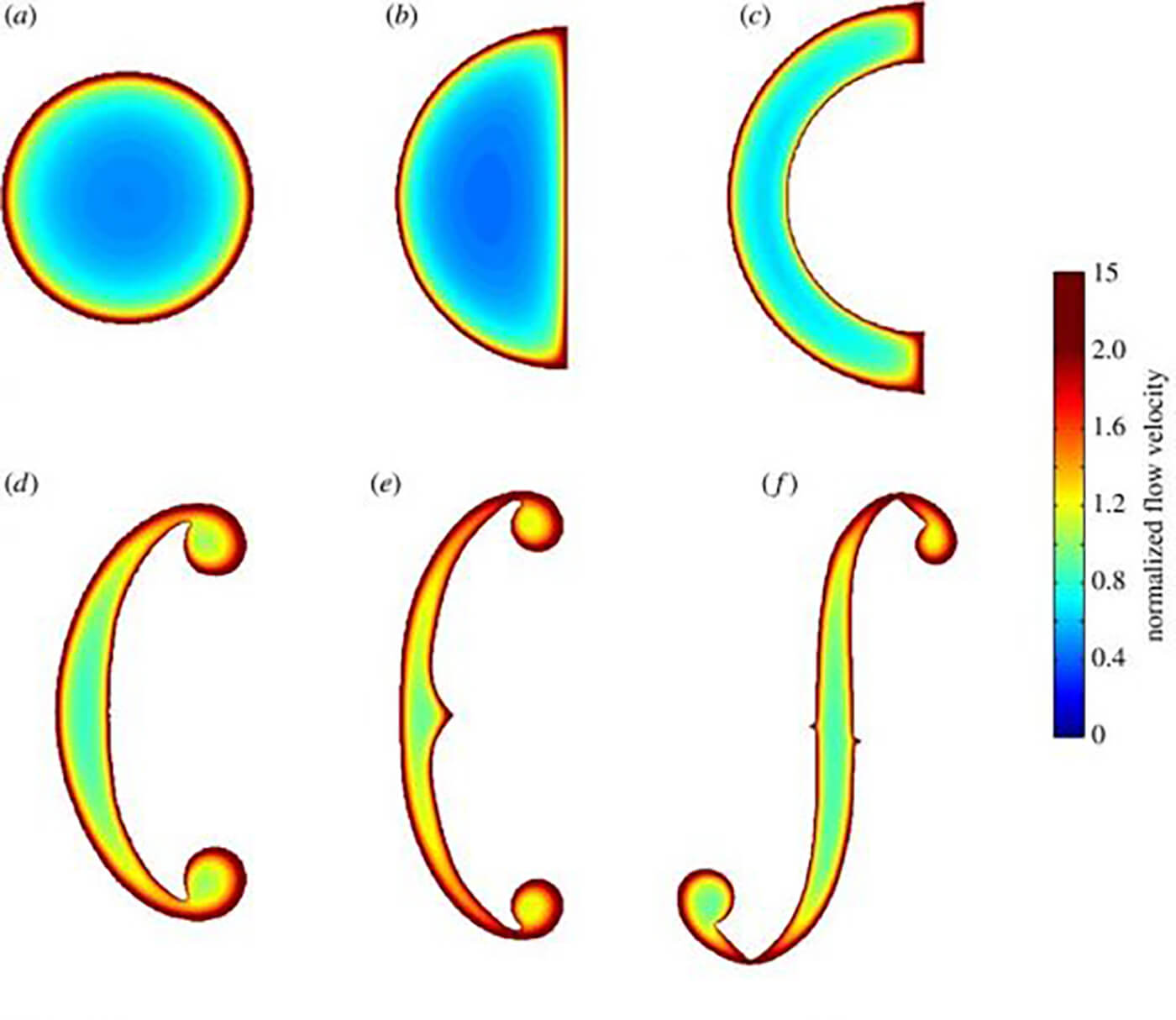

In fact, the earliest known f-holes were found on instruments made by violin makers Andrea Amati Gasparo de Salo, and Pietro Zanetto in the mid-1500s. Prior to that we found crescent or “C” shaped holes, and prior to that, as far back as the 10th century, bowed lutes had circular holes in the place we traditionally see f-holes today. These f-shaped cutouts not only looked very stylish, but they were also very functional for projecting sound on acoustic instruments, in a similar way that the soundhole on an acoustic guitar does.

Over several centuries then, we saw a slow evolution of the cutouts over the course of several centuries ending with the f-hole design that we know and love today, starting with the Gibson Lloyd Loar F-5 mandolin and the L-5 – the first modern guitar to sport what we now think of as a modern F-hole. But why did we land on that shape? It’s a question that has been pondered by many a luthier over the generations – especially given the fact that the shape seems to make instruments sound undeniably better.

In fact, there’s some truth in this – a 2015 study by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), published in the Royal Society of Publishing (RSP), found that air flow at the perimeter of sound holes conducts acoustics at a much greater rate. The further into the hole the sound gets the less it permeates, meaning that the size of the hole doesn’t necessarily impact the volume of sound whilst the edges of a sound hole allow for much more acoustic resonance.

We might not understand the specific mindset of the craftsman behind the first f-hole, but violin-makers and luthiers have understood this property in less scientific terms for a long time, and have spend thousands upon thousands of hours experimenting with ways to increase the circumference of the cutout by using other shapes, which has ultimately lead to the design of the common f-hole we know today.

It cannot be understated how remarkable this evolution is – luthiers in the pre-computer era didn’t have tools to measure air cavity resonance, they simply had to experiment through trial and error and using their ears. It seems very likely that the evolution came as a result of “craftsmanship error” as is suggested in the MIT study.

It’s certainly a valid theory, as they didn’t have CNC machines back then and replicating a cutout in during that era, using the tools they did, on the natural grain of wood, would have been nearly impossible. Still, these “errors” continue to resonate with musical instrument design to this very day.

F-holes Today

A lot has changed since then, of course, electricity ushered in a new way for stringed instruments to be amplified, and with that came a whole new set of sonic and resonance problems for luthiers to contend with.

Despite that, the presence of the humble f-hole has continued in some of the most iconic instruments ever made, from Gibson, Gretsch, Fender, Ibanez, PRS and many others – long after concerns for maximising acoustic volume had been solved by the magnetic pickup. So what gives? Does the f-hole serve any real purpose to these instruments beyond making them look cool? You can’t deny that the ES-335, the Country Gent, and the Thinline Tele would certainly be very different looking guitars without them.

Let’s take the Thinline Tele as perhaps the most extreme example – it’s far, far away from the jazzboxes that would have originally sported f-holes, and indeed even the body itself isn’t fully hollow but chambered. Given that the guitar was designed by Roger Rossmeisl, the maverick genius behind Rickenbacker’s 300 series guitars with their slash-shaped cutouts, why would he revert to the old-fashioned f-hole for the Thinline if not for purely aesthetic reasons? Well, let’s find out…

The real purpose of the f-hole on a Thinline Telecaster

Few people understand guitar sound better than Fender’s Chief Engineer and pickup guru Tim Shaw, and he was kind enough to share his thoughts on why a Thinline Tele has an f-hole.

“On hollow instruments with an f-hole, the motion of the bridge is driving the top, and the f-hole’s size and shape affects the resonance and overall tone of the instrument,” he explains.

“While a Fender Telecaster Thinline guitar has large hollow sections, the bridge is anchored to a very solid section of the body, and it’s not moving the top as it would on a hollow guitar. The f-hole here is mostly cosmetic; the tonal difference on a Thinline is more a function of the chambers than the f-hole itself.”

It’s a conclusion echoed by Fender’s Vice President, Research & Development, Stan Cotey “The earliest use of f-holes in musical instruments came from the violin, where it serves as an opening to a resonant chamber,” he notes. “With resonant chambers, the smaller the opening, the higher the pressure around it and the more resonant the sound.

“In the case of a Fender Telecaster Thinline guitar, I’m not super-convinced that the chamber really resonates much, and even if it did, I believe it would have to either influence the string’s motion (and therefore harmonic content) or change the pickup’s physical position in relation to the string to make much difference in electronic output. You could probably hear it acoustically, but whether that would translate into something that the pickups could grab is maybe debatable.

While these conclusions are focused on a Thinline Tele, you can probably draw similar conclusions to any guitar where the bridge and pickups are mounted on a solid centre block – those f-holes might look great, but they’re not adding a huge amount to the tone. The same might not be said for fully-hollow instruments such as an ES-330 or a jazzbox, but the impact on the tone is still likely to be minor and subjective.

But does it really matter? It might not serve much tonal purpose on a rowdy rock ‘n’ roll electric guitar, but the humble f-hole looks as at home today as it did on instruments 500 years ago, and that’s a remarkable feat by anyone’s standards. It’s also a lovely way to nod to the long history