Related Tags

All about… Acoustic Strings

Picking the right acoustic strings is like picking the right pickups for your electric guitar – and there are many factors to consider.

Lute maker shop and classic music instruments: young adult artisan fixing old classic guitar adding a cord and tuning the instrument. Close up of hands and palette

String theory

The drivers behind the evolution of acoustic guitar strings have been much the same as those that drove the development of guitar amplifiers – namely the quest for improved clarity and higher volume.

The six-string guitar as we know it began to become standardised only towards the end of the 18th century. Prior to that, octave and unison string pairs were used to achieve fullness and volume, and the practice continues with mandolin-style instruments. During that era, strings were made from animal intestines – hence the name ‘gut strings’. The plain strings were dried, scraped and twisted gut, while bass strings had gut cores wrapped with silver wire to add the mass necessary for low-frequency vibration without making them too stiff to be playable.

Genuine gut strings are still favoured by musicians who play early styles of music, and they are available from Aquila, Damian Dlugolecki, Pyramid and others. Some still use the term ‘gut-string guitar’ to refer to any classical-style instrument, but nylon plain and wire-wrapped nylon silk core strings are far more commonplace today.

During WWII, a shortage of materials prompted New York luthier Albert Augustine to try nylon line as a guitar string. He persuaded DuPont to start making nylon guitar strings and, despite a slow start, they became the classical string of choice after Andrés Segovia began using them.

By the mid-19th century, European and American acoustic guitar designs were evolving independently.

Most classical guitars are still based on the fan-bracing pattern perfected by Antonio de Torres. However, Christian Frederick Martin developed an X-bracing pattern that was conceived for gut strings but only realised its full potential half a century after his death, with the advent of steel strings.

From the 1880s, improved wire drawing technology led to the development of steel strings known initially as ‘mandolin wire’. These new strings made instruments from the mandolin family and banjos louder than ever before. The small-bodied gut-string guitars of the era couldn’t compete, and for a while they were relegated to the parlour. Orville Gibson and the Larson brothers were amongst the first guitar makers to respond. They developed archtop guitars built more like violins, that had the inherent strength to withstand the increased tension of steel strings.

Although the basic structure of the X-brace was almost strong enough to cope with steel strings, Martin remained cautious until 1922 when it reintroduced the Style 17 with a heavier-braced mahogany top and steel strings. It was such a success that the Style 18 and 28 models were soon similarly outfitted – and by the mid 1920s, steel strings were standard on Martins, and gut strings had become optional.

Steel-strung archtops powered the rhythm sections of the jazz age and steel-strung flat-tops did the same for country, blues and folk players. Before long, the guitar buried the banjo, and it has remained the most popular stringed instrument. Let’s, then, take a closer look at the way steel strings are made.

Core strengths

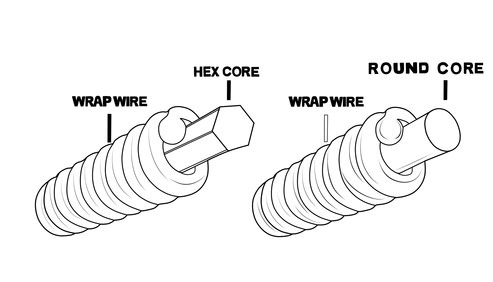

Drawn wire has a round cross-section, and for the first few decades, steel string sets had wound strings that were manufactured much like the old gut strings. However, instead of a gut or nylon core, the windings were wrapped onto a round steel core.

Unfortunately, the smooth and slippery round core wire provided a less than ideal surface for holding the windings, and it was common for wound strings to loosen or even unravel and go dead. String manufacturers solved the problem by developing a method to draw core wire with a hexagonal cross-section that provided more grip for the outer windings.

Hex-core strings have a brighter and clearer tone and they are less prone to mishaps when stringing up, but they lose their initial brightness quite quickly. A hex core doesn’t allow such a pure orbit of vibration, and some feel that round-core strings have a nicer tone.

Also, the spaces between the wrap wires and the core are much smaller, so dirt and contaminants don’t build up as quickly with round cores. They may not be as bright to start with, but round cores maintain the same tone for longer and many guitarists find that they are easier to play.

Remember those great acoustic tones from the 50s and 60s all came from round-core strings. They won’t suit everybody, but if you want to try some, check out Newtone, Pyramid and DR Strings.

Alloys

Although the plain strings and cores are always made from corrosion-resistant steel wire, the wrap wires can be made from different alloys that all have specific tonal characteristics. The most common alloys are designated phosphor bronze and bronze.

The difference is in the alloy composition, which is a mixture of copper and tin. Phosphor bronze strings have a higher proportion of copper, and are sometimes described as 92/8 (92 per cent copper, eight per cent tin). Bronze strings have a higher proportion of tin, with an 80/20 ratio – and some companies, such as D’Addario, make ‘in-between’ sets with an 85/15 mix.

Bronze strings generally sound bright, but also fatter and bassier than phosphor bronze. In contrast, phosphor bronze has more clarity, definition and sparkle, but doesn’t sound quite as full in the midrange. Strummers might prefer the 80/20s, but 92/8s should suit fingerstylists and dropped open tunings.

A naturally occurring alloy containing 67 per cent nickel, 32 per cent copper and some iron was found in an Ontario mine back in 1906 and named ‘monel’. Gibson used it to make strings in the 1930s, due to monel’s high resistance to corrosion.

Monel is used most commonly for bass strings, but several companies have reintroduced monel acoustic strings for players chasing old-school tone. On the right guitar, they offer superb clarity without excessive brightness, they’re full without sounding tubby and bass definition is superb. String-to-string balance is very smooth and they maintain their tone far longer than the usual alloys.

Live long and phosphor

When you’re playing an electric guitar, you can always turn up the treble once new strings have lost some of their brightness. When you’re playing an acoustic guitar (acoustically) there’s nothing that can be done about dull string tone.

If you wear out strings quickly but prefer brighter guitar tone, the cost of regular string changes can be prohibitive. One option to consider is using a set of long-life strings coated with Gore-Tex such as Elixir Nanowebs. You can find coated bronze and phosphor bronze strings, and the coatings come in various thicknesses. Some manufacturers coat the entire string and others coat the winding wire before it’s wrapped onto the core.

Coated strings – particularly those with thick coatings – are naturally a little duller-sounding than equivalent non-coated strings, but they retain their ‘out of the packet’ tone for longer. You may also notice less friction and string squeak as a result of the coating. This aspect divides opinion, as some dislike the ‘feel’ of coated strings.

Of course, not everybody likes the bright tone of fresh strings. If you’re one of those players, there’s not much point in paying extra for coatings that will maintain the characteristics you dislike for even longer. Some miss the fresh-string zing that most coated strings don’t provide, but take a view that they sound better over a longer period.

The pragmatic player may choose coated strings for practising and gigging, and non-coated strings for recording. Although they’re not for everybody, coated strings are certainly worth a go, but be sure to research the specs before buying.

Feel the tension

Not all acoustics are created equal. Some have thick soundboards and/or heavy bracing, and light-gauge strings may not be able to generate sufficient energy to drive the top and make the guitar sound its best. Conversely, heavy-gauge strings can be too much for lighter guitars.

When steel strings became standard, Martin found itself busy repairing pulled-up bridges and bellied tops.

The bridges and bracing were beefed up to cope with the extra tension of increasingly heavy string gauges, and scalloped bracing was eventually phased out altogether. The whole vintage guitar thing really started in the early 60s as folkies discovered the superior response and dynamics of Martin’s pre-war models.

You should also consider playability when selecting string gauges. The best guarantee of good tone is a guitar that feels good to play, and it’s pointless to struggle with overly heavy strings for the five minutes of sonic nirvana you’ll enjoy before your fretting hand starts to cramp up.

If the string-to-string balance sounds a little uneven on your guitar, you should consider fitting a custom string set. For inherently well-balanced designs such as an OM or 000, some may appreciate sets where every string exerts a similar tension when tuned to pitch.

Alternatively, you could try lowering the gauge of the wound strings while retaining heavier plain strings if your dreadnought sounds too boomy. Using heavier low strings can also help to retain definition and volume if you regularly play in dropped tunings.

Some manufacturers market string sets that are designed specifically for DADGAD players, and many provide tension information for those aiming to assemble even-tension sets. It’s also worth checking out some of the low-tension sets that combine big-string tone with thin-string playability by changing the core-to-wrap ratio.