Related Tags

All About… Doc Kauffman

Leo Fender’s decision to get into the guitar-manufacturing business was perhaps surpising given that he didn’t play the instrument himself… but he knew a man who did. Without Doc Kauffmann, Fender guitars and amps might never have existed.

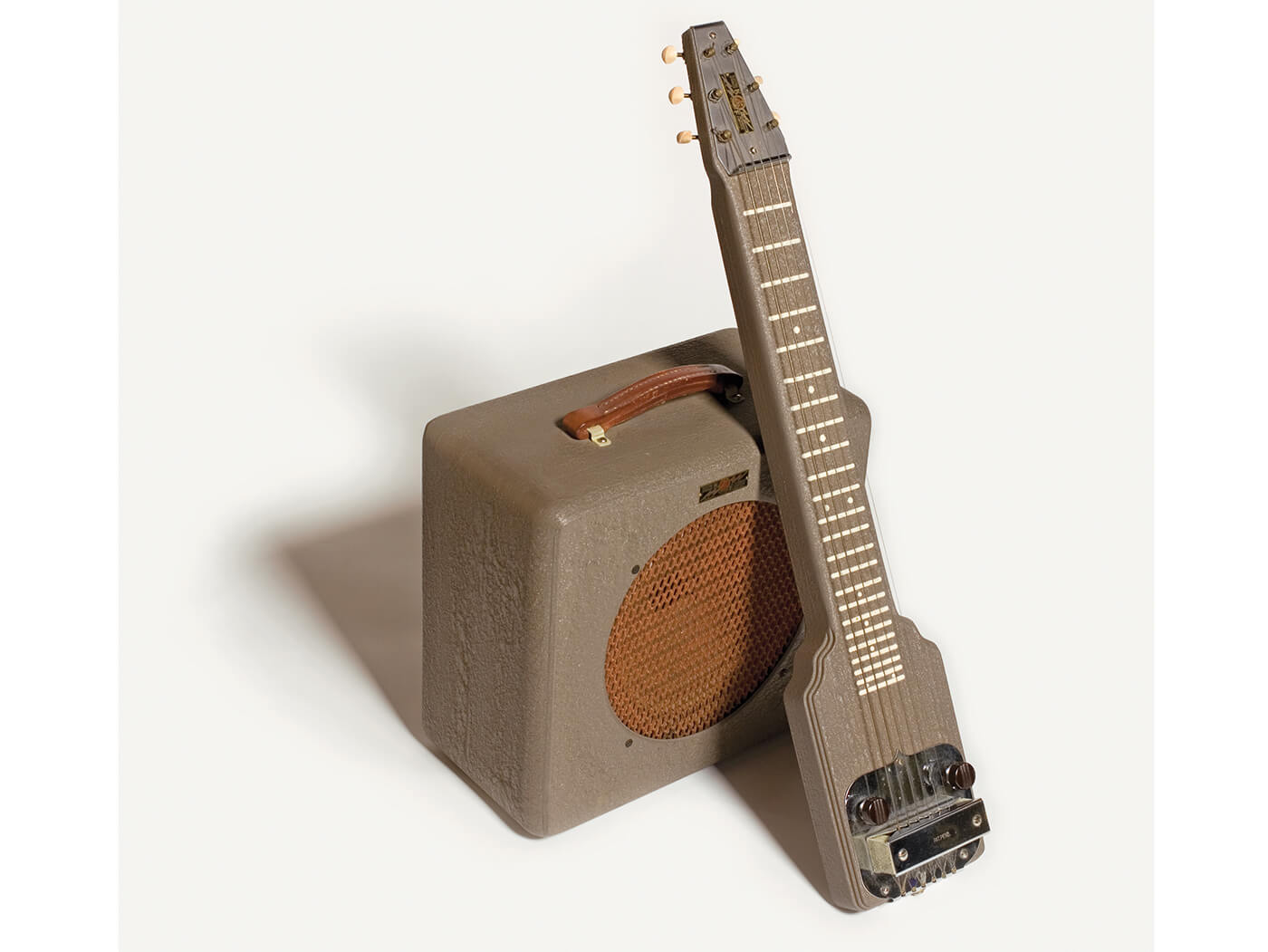

Image: Paul Kelly, ‘Fender: The Golden Age’

Like Leo Fender, Clayton Orr ‘Doc’ Kauffmann came from a farming family. Doc moved to California from Pratt County, Kansas in 1920 – he’d studied violin and could play guitar and saxophone, so he landed a job providing musical accompaniment for silent movies. After returning to Kansas and getting married, Doc was back in California by 1922 and working as an instrument repairer and piano tuner.

Although guys who tinkered around inventing stuff were often called ‘Doc’, that’s not how Doc Kauffman got his nickname. One day he arrived at the wrong address and was ushered into a room where a woman was having a baby. Seeing the black bag he carried for his piano-tuning equipment, the family had assumed he was a doctor. When his colleagues found out, they started calling him Doc and it stuck.

As a youngster, Doc was always building things – including steam engines, milk cans, farm machinery, tools, radios, police transmitters and even a motorcycle. In California, he worked on musical instruments, and designed a pitch-changing device to liven up an uninspiring tenor guitar. Later, he built one for a six-string Gibson, which he’d use with one of his home-made amplifiers.

Doc ’N’ Vibrola

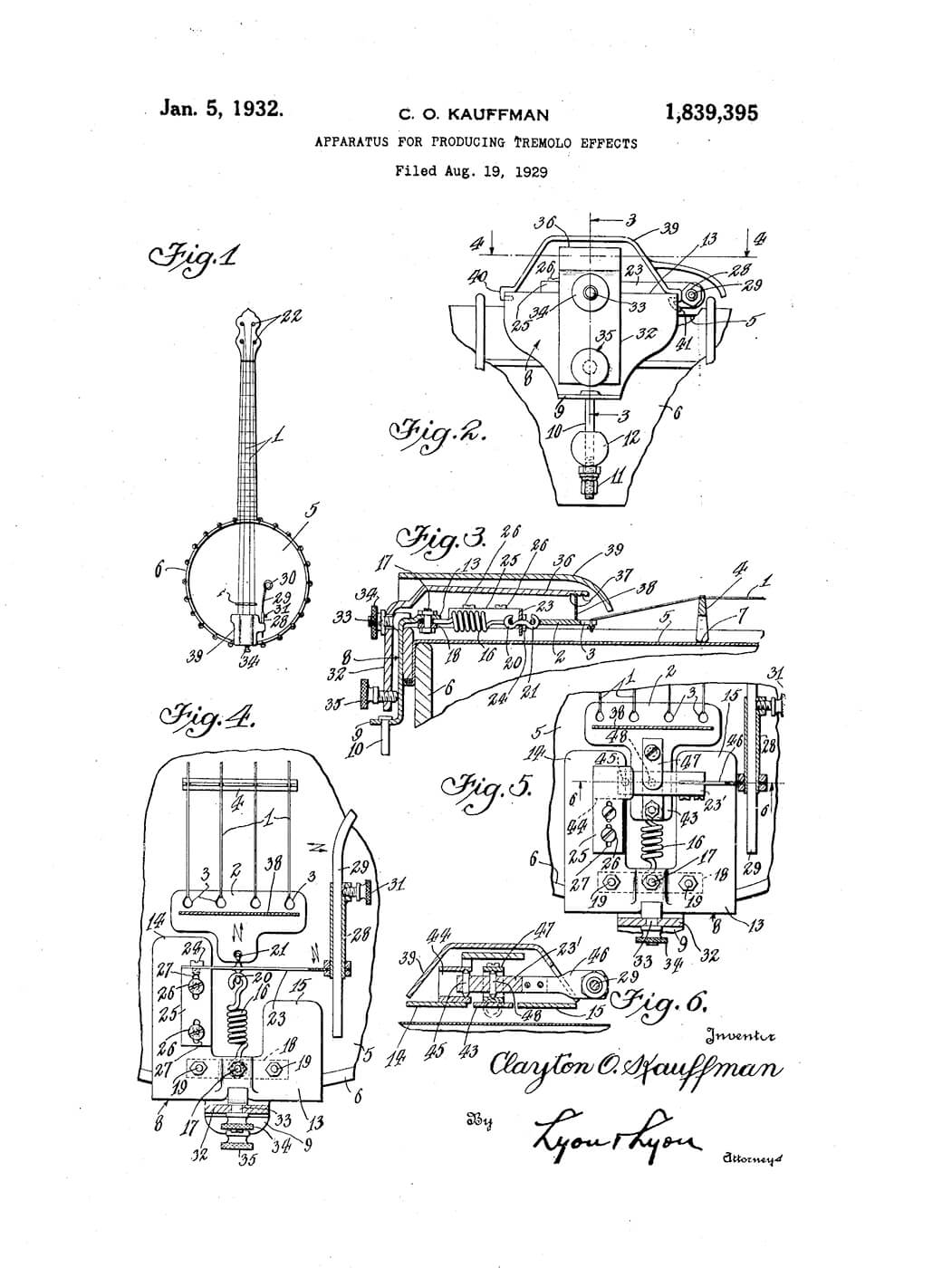

Doc’s patent application for an ‘Apparatus For Producing Tremolo Effects’ was filed 19 August 1929 and granted 5 January 1932 (US1839395A). Strictly speaking, pitch-shifting is properly called vibrato, but throughout his patent application, Doc used the term ‘tremolo effect’.

Later on, the Fender Stratocaster would have a ‘Syncronized Tremolo’ bridge and on any Fender amplifier with a tremolo circuit, the effect would be described as ‘vibrato’. So Doc’s misunderstanding – if that’s what it was – has been perpetuated to this day.

In 1929, Doc met George Beauchamp, who was working with Paul Barth and Adolph Rickenbacher at the National String Instrument Corporation. The trio formed their own guitar company in 1931 and by 1933, it was trading as Rickenbacker Electro. Although Doc was good friends with all three men, there was no job for him, but he did strike a deal for Rickenbacker to manufacture and market his ‘tremolo’ and it became known as ‘The Rickenbacker Vibrola’.

As probably the first commercially available mechanical vibrato device for stringed instruments, Doc’s Vibrola was originally fitted to early Rickenbacker lap-steels. This is significant, because the Vibrola’s arm moved in an arc across the strings, rather than up and down. It made perfect sense for playing lap-style, but proved less popular when Gibson later revived the idea with the remarkably similar Sideways Vibrola.

Considering it pre-dated Paul Bigsby’s design, Doc’s device clearly worked well enough. His old friend Les Paul used them on his guitars for many years, including the infamous ‘Log’ and the early Goldtops. Chet Atkins had Doc’s Vibrola fitted to his D’Angelico and the Gretsch 6120 prototype, and Rickenbacker continued using it well into the Rossmeisl era.

Doc also designed a guitar with an integral motor and an offset cam that could produce an automated vibrato effect. Rickenbacker introduced it as the Vibrola guitar in 1937

at a price of $175.

The Doc is in

Leo Fender told Tom Wheeler: “I had seen Doc back in the mid 1930s. He used to play in storefronts to draw a little business for the store and also to sign up a few students for himself. But I didn’t meet him and talk to him until maybe 1941.” Doc recalled of that meeting: “Leo came in one day and he said: ‘Hey, you’ve been building guitars around here, do you want to build some together?’ And I said: ‘Well sure, sounds okay to me.’”

By now, Doc was much more than a hobbyist. He’d been building and selling amplifiers and Rickenbacker-style lap-steels, even winding his own pickups and using magnets from a Ford Model T car. Leo was struggling to make decent-sounding pickups, so he must have been intrigued to learn Doc had a winding machine from Rickenbacker.

Initially, Doc carried on working for Douglas Aircraft and did after-hours repairs at Leo’s place. By 1943, Leo and Doc had built their first solidbody guitar, which they’d hire to local musicians. The guitar was in great demand and clearly Leo must have spotted the commercial potential in making solidbody electrics, but in the meantime, he and Doc concentrated on building lap-steels and small amplifiers under the K&F monicker.

It was apparently Doc’s idea to dispense with the then-common practice of mounting the amp chassis at the bottom of a cabinet. He reasoned that moving it to the top would keep the electronic components safe and the controls would be easier to adjust.

They also built a record-changing device that raised about $5,000 and although the business was doing well, Leo recalls that: “K&F began to take up so much of an investment that Doc began to get worried, and he was afraid that some property he had in Oklahoma might go down the drain if we failed.”

According to Doc: “I got scared of the business. I had been saving money through the war, and I wanted to get a home and pay for it. My dad was a credit boy all his life, owed money on the farm and everything, so I told myself I’d never go into debt.” He was also aware that Leo had no such qualms. “I didn’t have much faith in guitars,” Doc admitted, “and I asked Leo to buy out my half of the business.”

According to Leo: “Doc had released everything to me; he took a small punch press and we called it an even trade.” So, the K&F company lasted only from the autumn of 1945 to around February 1946. When Leo founded Fender Manufacturing in 1946 and the Fender Electric Instrument Co. the following year, he carried on using K&F nameplates until they were gone. Employees were retained, too, including a recently demobbed Don Randall.

Life after Leo

Fender historian Richard Smith reveals Doc “considered himself an inventor, not a businessman”. After leaving K&F, he returned to building guitars and doing instrument maintenance from a workshop at his family home. Doc also received some money from an inheritance in Kansas and during the 1950s, he opened a small machine shop turning out aircraft parts. He played professionally, too, working with big bands and orchestras. According to his son Kenneth, Doc even played with the Radio Station Orchestra alongside Jack Benny.

He carried on gigging almost to the end of his life, playing popular songs from the 1930s with home-made guitars and amps. Doc’s daughter Maxine describes Doc as “a folk hero to a lot of guitarists of all ages. They were devoted to him”. Richard Smith knew Doc well and describes him as “a real, real nice guy, and he was a fine musician”. Others describe him as kind and funny. Later in life, Doc asked Leo what he would have ended up doing if they had never met. Leo replied: “Well, I’d probably have maybe two or three radio stores or TV repair shops.” Leo also told Robb Lawrence: “If it hadn’t been for Doc kind of pushing me into it, I probably wouldn’t have gotten into the guitar business.”

Had Doc stuck it out with Leo, he could have become a very wealthy man, but his son Kenneth told The Orange County Register: “There were no hard feelings on dad’s part, they were still friends. Leo would visit dad and they would reminisce.”

This is quite something, considering very few people ever claimed to have been a friend of Leo’s. More extraordinary still, Doc actually listed Leo as next of kin after his children in his will and the two men remained close right up until Doc’s death in 1990, aged 89.