Related Tags

All About… Nitrocellulose

When Edmund Flaherty invented nitrocellulose lacquer in 1921, he could’ve had no idea how big a role it would play in the guitar industry. G&B explains…

Henry Ford once remarked that customers could order a Model T in any colour they wanted, so long as it was black. The reason was that ‘Japan Black’ lacquer was one of the few widely available metal coatings available at the time, and its fast-drying characteristics were indispensible on Ford’s assembly line.

That changed with the development of nitrocellulose lacquer in the early 1920s. The new lacquer dried even faster, and it could be applied using spray guns. Best of all, an infinite colour palette was opened up. Nitrocellulose was adopted quickly by the car industry and remained the finish of choice through to the late-1950s.

Furniture and musical instrument manufacturers also switched to nitrocellulose lacquer, and mostly it was referred to simply as ‘lacquer’. Pretty much every collectible acoustic and electric guitar made up until the mid-1960s left the factory with a nitrocellulose lacquer finish.

What is it?

Cellulose is an organic compound comprised of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Found in the cell walls of plants and algae, it’s the most abundant organic polymer on earth. The human body uses cellulose as a dietary fibre, and cellulose-derived products have been used in the photography, clothing and explosives industries since the mid-19th century.

In 1862, Alexander Parkes treated cellulose with nitric acid and a solvent to create the first man-made plastic – nitrocellulose. The process is virtually identical to the way in which trinitrotoluene (aka TNT or dynamite) is produced, which is not unrelated to the authorities’ keenness to limit its use in industry.

A DuPont employee called Edmund Flaherty invented nitrocellulose lacquer in 1921. Nitrocellulose is dissolved in a solvent, which may comprise naphtha, xylene, toluene, acetone, various ketones, and plasticising materials that enhance durability and flexibility. The resulting liquid can be sprayed and the extremely volatile solvent thinner evaporates almost immediately, to leave behind a layer of nitrocellulose solids.

When subsequent coats are applied, the thinners melt the surface of the previous coat, allowing the fresh coat to bond with it. In that sense, nitrocellulose lacquer is very similar to shellac, which is another natural polymer lacquer with an even longer history. However, nitrocellulose lacquer is tougher and more scratch resistant.

Nitrocellulose lacquer also takes pigments and dyes very well, and it can be sanded and polished to a mirror finish. Its enduring popularity as an instrument finish is based on its beautiful depth and lustre, its ability to protect wood without inhibiting resonance and a supposed ability to ‘breathe’. It also enables you to perform drop-fill repairs to chips and polish out superficial scratches.

However, nitrocellulose lacquer dries slowly compared to modern finishes and it’s far more time consuming and labour intensive to achieve high-quality results with it. In addition, the chemicals in the lacquer are hazardous to health and the environment, and – since it’s highly flammable – it’s dangerous to store nitrocellulose lacquer in large quantities.

Plasticisers

The word ‘plasticiser’ sets alarm bells ringing for nitrocellulose die-hards. After all, if nitrocellulose is meant to be more beautiful and toneful than plastic poly finishers, wouldn’t putting a plasticiser in the nitro defeat the object?

This is a misunderstanding, because plasticisers are not plastic. ‘Plasticity’ is defined as the ability to deform irreversibly without breaking. So placticisers are solvents that evaporate slowly over several years to prevent nitrocellulose from becoming too brittle. They don’t turn nitrocellulose into a ‘plastic finish’ because nitrocellulose is, after all, a type of plastic.

It’s understandable that paint makers and guitar manufacturers wanted their finishes to look good for as long as possible. Plasticisers make nitrocellulose more durable and less prone to checking and chipping, so it’s hardly surprising that their use became widespread.

Even back in the 50s and 60s, lacquer had placticisers, and it became an issue only for those who prefer their finishes to age in the vintage style, or for would-be relic’ers who couldn’t get their lacquer to crack.

Formulations

“They don’t make ’em like they used to” is a general-purpose truism that is often applied to nitrocellulose lacquer, and two things are certain. Firstly, all the big guitar companies in the 50s and 60s were using lacquer from various manufacturers and the formulations were slightly different. Secondly, the balance of ingredients used in modern nitrocellulose lacquer has changed substantially from what it was back in the day.

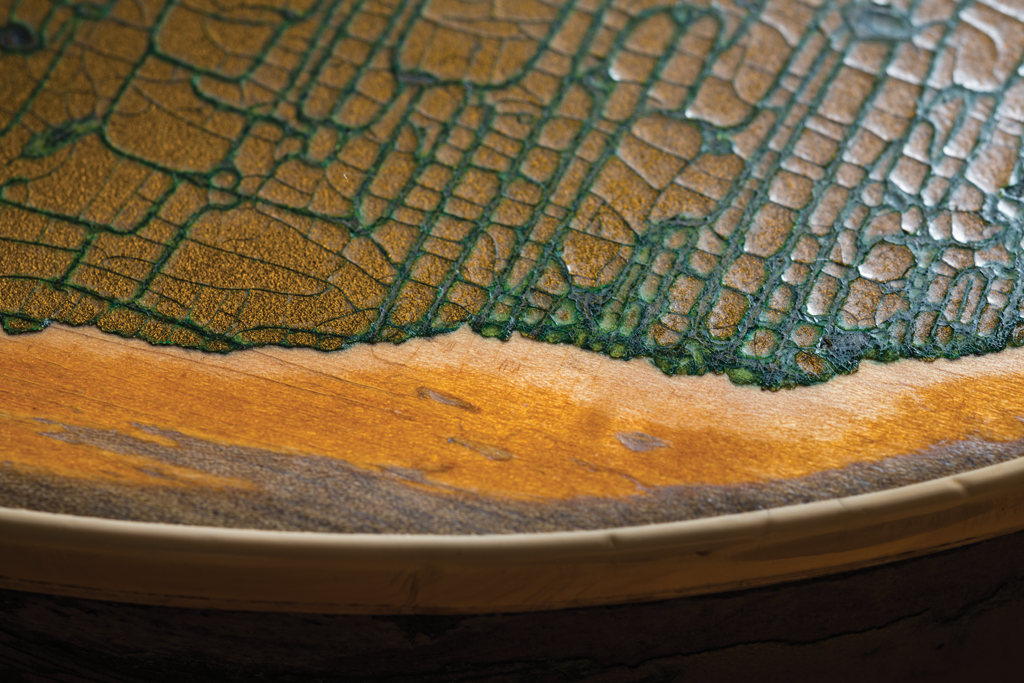

Old lacquer was seen as having certain undesirable traits. It tended to yellow up with exposure to UV light; colour pigments often faded; temperature fluctuations caused cracking (checking) and sometimes, the lacquer would start flaking off the body. Curtis Novak is a man who knows as much about vintage finishes as he does about pickup making, and he explained some of the changes to us.

“Over the years, they have ‘fixed’ the inherent problems with nitrocellulose lacquer, where it no longer yellows or cracks with age. Compared to the old stuff, they might as well call it acrylic lacquer, because that is more what it represents. The first test I do when shopping for vintage nitro is have them open the lid. The vintage stuff looks like tea, modern stuff looks more like canola oil.

“Many people think that the old nitro aged over time and, yes, that is true, but it was already very dark right from the can. Generally, if it passes the visual test, it is the old stuff and will crack very easily. The new finishes are softer, which is what prevents them from chipping and checking. As for the thickness, lacquer is forever gassing off, so over time, it gets thinner and thinner. The vintage ones were once much thicker finishes.”

Not all the changes were made to improve the lacquer’s durability. According to George Gruhn, the Occupational Safety And Health Administration in the US “forced makers of finishes to change their formulas over the years. While the new formulas may be less toxic, in most cases they simply don’t produce the same appearance or tonal results as the earlier formulations.”

Former Fender senior finish specialist Jonathan Kornau reports: “The old McFadden’s formula, with the exception of one maleic resin, is still available. Lots of companies still make nitrocellulose without acrylic resins. Sherwin-Williams Opex and the Mohawk lacquers are all nitro. The solvents and plasticisers are always changing due to EPA regulations; it’s possible to buy the old formulas, with only the solvents having changed. When cured, they would be the same.” Sadly, US-manufactured lacquer isn’t available in Europe, because it’s too volatile to ship internationally.

What lurks beneath?

Although the vast majority of vintage guitars had nitrocellulose lacquer finishes, many didn’t. Some had finishes that were part nitro and part acrylic, nitro and polyester or even a combination of all three.

Around 1963, Fender began using a clear polyester sealer called Fullerplast. After dying the bodies yellow, they were dipped in Fullerplast, which dried rapidly to form a flat coating for nitrocellulose to be sprayed on top. This eliminated the need for grain filling and meant the expensive nitro could be sprayed thinner without sinking into the grain – so Fullerplast saved Fender time and money.

DuPont made nitrocellulose lacquer called Duco and acrylic lacquer called Lucite. Fender used both, and Olympic White, alongside all the Fender metallic finishes, was actually acrylic.

Mostly, Fender sprayed nitrocellulose clear coats over the acrylic coats, and because the clear coats yellowed and checked over the years, many people have assumed wrongly that these finishes were pure nitrocellulose. Fender also sprayed acrylic over rejected Sunburst finishes to fulfil custom-colour orders.

To complicate matters further, from possibly as early as 1956 DuPont started using acrylic binders in its nitrocellulose lacquer to prevent yellowing and colour fading, and to inhibit checking. Even more confusing is Gibson’s use of the word ‘poly’ to describe its metallic finishes, when they were acrylic like the rest of Gibson’s custom colours.

Although nitro-finished guitars are still available, the practice of spraying nitro over acrylic and poly base coats has continued. If you subscribe to the idea that a thin nitrocellulose finish is the best option for resonance and allowing the wood to ‘breathe’, it’s worth finding out if that lacquer finish is what it purports to be before paying a premium price for it.

DIY dos and don’ts

These days, we have to make do with whatever nitrocellulose lacquer we can get, and very few of us own professional spraying equipment. Fortunately, there are several companies in the UK that supply lacquer in aerosols, and most of the classic colours are available – along with clear and tinted varieties.

You must bear in mind that spraying nitrocellulose lacquer exposes you to some really nasty toxins. Ideally, you should set up a booth with a proper extraction fan if you plan to do a lot of spraying. It is also essential to wear a breathing mask that can block out vapour as well as airborne particles. If you go to a good car paint supplier, they should be able to advise you on the most suitable mask to buy.

You will also find that spraying nitrocellulose without an extractor fan creates huge quantities of dust and isn’t healthy for anybody or anything. Spraying outdoors on dry days when there is little or no wind is ideal, but opportunities are few in the UK.

Spraying guitars is an absorbing hobby, and with practice and patience you can achieve results that will rival the pros. And if you goof up the finish, you can always relic it.

Buyer’s guide

For classic Fender and Gibson colours, you’ll need to go to specialist suppliers, but all the colours are available. The days when you could find nitro lacquer in car-accessories shops are long gone, but you can still get clear lacquer from furniture-finish suppliers. Here’s a selection.

Manchester Guitar Tech £15 per can

Steve Robinson supplies a full range of classic colours and more besides. We have achieved some great results with Steve’s lacquer because it sprays evenly,is run-resistant and cracks only when you want it to.

Rothko and Frost £11.95 to £16.75 per can

Another UK supplier that sells a wide range of coloured and clear lacquer. In addition to aerosols, Rothko and Frost sells brushing lacquer for those who prefer not to spray.

Fiddes & Son LTD BoneHard £13.04 per can

This Cardiff-based company sells a huge rage of stains, base coats and finishes. Having used the Bonehard lacquer, we can report it yellows up nicely and will check easily, but spray thin coats if you want to avoid runs. Aerosols are made to order.

Morrells $9.23 per can

This is another clear lacquer that’s suitable for furniture and guitars and it’s priced reasonably. Morrells lacquer is available in gloss, satin, semi-matt and matt.