Related Tags

All About… Rectification

We complete our series exploring the role of the valve in guitar amplification with a look at rectification. Huw Price explains the twin functions of this vital yet relatively unheralded amp component…

The word ‘rectification’ is used a lot in these pages. We talk about valve rectifiers, solid-state rectification and even dual rectifiers, but what does it actually mean?

The mains supply from the wall socket comes with an alternating current – AC. Guitar signal flowing through an amp also has an alternating current, so as far as your amp is concerned the raw wall supply is both power and noise.

Nevertheless, amps need power, so the ‘noise’ element must be eliminated. That means the wall AC has to be converted to a direct current – DC. No amplitude means no noise. For the most part, the conversion process takes place within a section of the amplifier known as the power supply.

Typically, a handful of components are used in the power supply. The mains is connected to a power transformer that will have output taps for the various voltages needed for different functions within the amp.

The highest voltage taps, which are typically higher than the mains voltage, are connected to the rectifier. The rectifier’s output connects to a network of dropping resistors and capacitors and, all being well, the power supply output will be clean and silent DC.

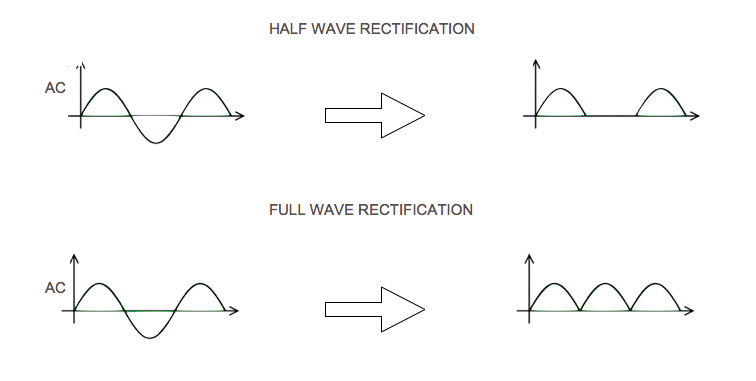

Every guitar amp has a rectifier, and its role is twofold. It generally raises voltage levels and begins the AC to DC conversion process. The simplest ‘half wave’ rectifiers simply block either the negative or positive phases of the cycle. Full wave rectifiers create a constant polarity, so the positive and negative cycles all become fully positive (or fully negative).

The rectifier output is actually a pulse, which is then smoothed to flat DC by the filter capacitors. Although there are various methods of rectification, those found in guitar and bass amps fall into two broad categories – valve and solid-state. Let’s take

a closer look at each type.

Valve rectifiers

We’ve investigated pentode, tetrode and triode valves over recent issues, but so far we haven’t mentioned diode valves. Even so, many amplifiers will have one as the rectifier. Since all valves were diodes up until the triode was invented, they were simply called rectifiers.

The simplest diode valves have no control or suppressor grids, just a heater, cathode and anode. AC from the transformer is connected between the anode and cathode. The heated cathode releases electrons and when the AC is in its positive phase, the plate attracts the electrons and current flows. When the anode is negatively charged, no electrons are attracted and no current flows.

So diodes allow current to flow in one direction but not the other – just like a non-return valve in a water pipe. That’s why the term ‘valve’ was coined, and it’s why Americans have a valid point when they say it’s archaic when applied to triodes, pentodes and so forth. Incidentally, diode valves were also used to form logic gates, so they were pivotal in the development of computing.

Solid-state rectifiers

Solid-state (or semiconductor) diodes are just as old as diode valves. However, they remained less stable than valves for quite some time. Manufacturing technology improved and reliable long-life diodes were eventually developed, so solid-state rectification became commonplace in guitar amps.

Solid-state diodes are tiny in comparison to diode valves, many seem to last indefinitely and they simplify the manufacturing process because they don’t need a separate heater supply and specially designed power transformers. They’re also significantly cheaper. Ultimately, a solid-state diode has an anode and a cathode, just like a diode valve, and in a rectifier configuration they do exactly the same job.

Rectifiers and tone

It has often been said that rectifiers have no effect on tone because they are not in the signal path. The second part of that is true, but the first part is more complex, and much depends on how you conceive ‘tone’.

Sound and tone are much like resistance and impedance. In some regards, they are the same, and the terms we use to measure or define them are often identical. However tone, like impedance, is a more complex phenomenon.

My perspective is that tone obviously means sound, but it also encompasses dynamic response, breakup characteristics, transient response and bass frequency definition. While the rectifier doesn’t necessarily influence the ‘sound’, it impacts everything else.

The simplistic ‘valves are good and solid state is bad’ cliché doesn’t apply to rectification. It all depends on the type of response you want from your amplifier. The technical ‘failings’ of valve rectifiers are the very reason that so many guitarists prefer them.

Michael Soldano explains the ‘technical shortcomings’ of valve rectifiers: “A tube rectifier has internal resistance. The more current that travels through a tube rectifier, the more the voltage drops. When the voltage drops, the power of the amplifier drops. The tube rectifier has the drawback of not being able to provide a consistent voltage when it’s under load.”

You may not notice any difference between solid-state and valve rectification when you’re playing quietly. However, if you crank up a valve-rectified amp and hit a powerchord, the internal voltages drop with the extra current demand and the dynamic range of the amp is reduced. This is commonly called ‘sag’, a form of compression that can make an amp feel touch sensitive and smooth.

It’s a characteristic of countless vintage amps, and players who are used to rectifier sag often find it hard to play without it. The downside is that the bass end can be spongy and lacking in definition. In contrast, solid-state rectifier diodes have no internal resistance, so there is no current limiting and they can deliver a constant supply of voltage regardless of demand.

Tighter and punchier amps are required for more aggressive styles such as modern rock and metal, so that’s why amps with solid-state rectification are more popular with heavy-rock players. The transient response is quicker and the tone more consistent.

When valve rectifiers sag and voltages drop, there can be a subtle change in sound. Preamp and power valves may distort quicker at lower voltages with some diminution in treble response that adds a certain sweetness. As the transient attack is reduced and the level drops, you can hear a ‘bloom’ effect as held notes seem to sustain longer because volume increases as voltage levels recover. Experienced players who are into this kind of thing will dial in an amp to exploit those characteristics – in effect playing the amp as well as the guitar.

Rectification mods

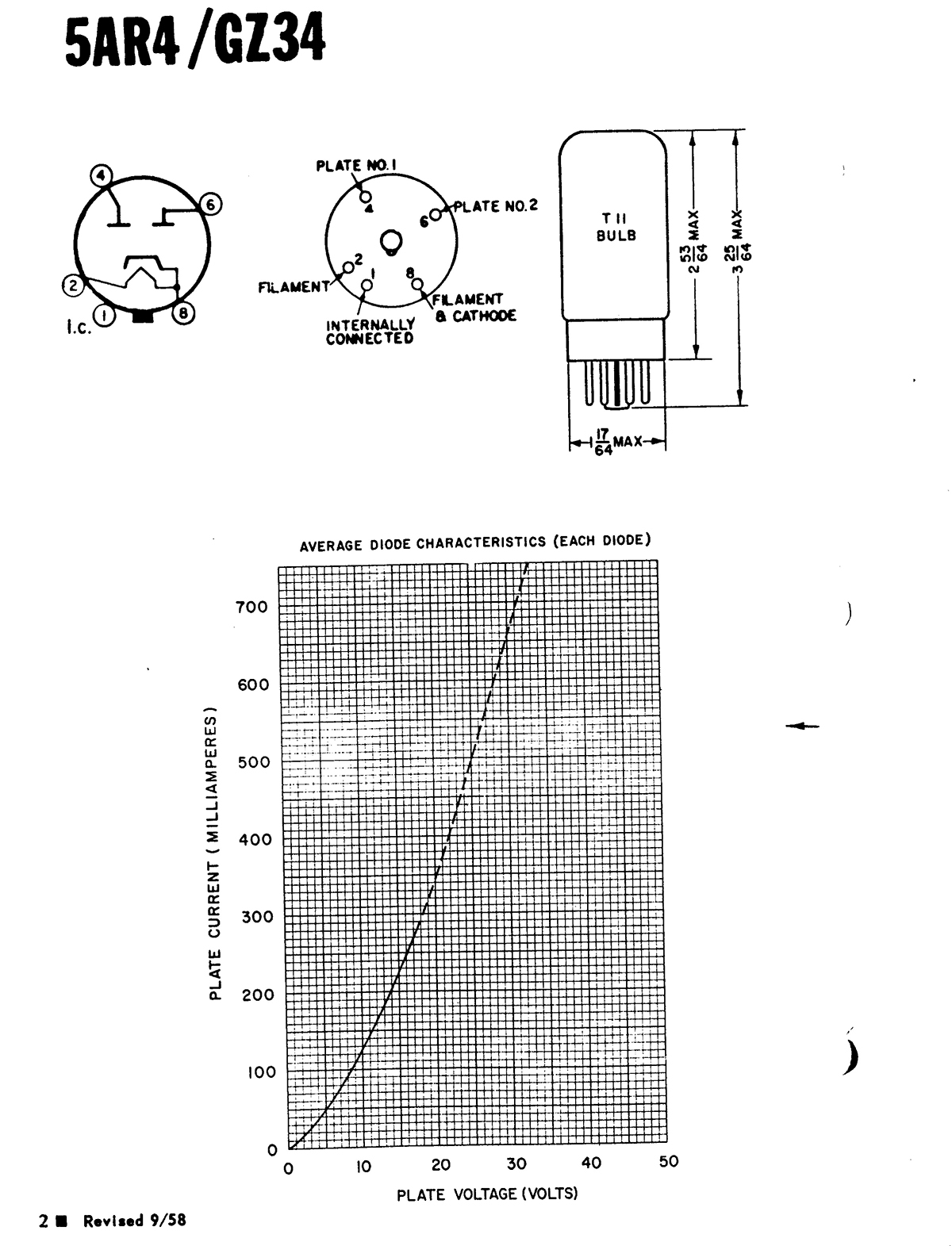

Not all rectifier valves are equal. The common complaint about current ones is they’re not as reliable or durable as vintage versions. What’s more, they all put out different voltages, so one GZ34 will probably be different to another GZ34 – even if they’re the same brand. Internal voltages have a bearing on tone, so the simplest mod is to try a bunch of rectifiers of the specified type.

Most rectifiers fit octal sockets, so some are interchangeable. Some players will replace the stock 5Y3 rectifier in medium-sized tweed amps with a GZ34 (aka 5AR4) to increase clean headroom and tighten up the bass. The 5V4 is another popular option, but you may want to have the bias checked with a new rectifier installed. If you want more sag, you can sometimes install a lower-rated rectifier valve.

Some have tried 5Y3s and 5V4s in Princeton-style amps to make them less stiff, but if you’re considering rectifier swaps, they must be compatible and capable of meeting the amp’s current draw. The rectifier itself draws current from the power transformer, so make sure it’s not going to be excessive.

Often, the safest way to determine these things is to consult old-fashioned tube charts. Total up the current draw of the preamp and power valves and compare that figure with the current rating of the rectifier valve.

If the current draw exceeds the maximum for that rectifier, you can’t use it. If you really need to tighten up a valve-rectified amp, or simply avoid having to buy a valve rectifier again, you might consider installing a solid-state rectifier.

Some, such as Weber Copper Caps, are designed to emulate the sag characteristics of the valves they’re replacing and they even have a warm-up time, so they’re safe to use with non-standby amps.

Others, such as the Mojotone Solid State Rectifier and the Yellow Jackets YJR, slot straight into a rectifier valve socket to provide solid-state rectifier performance without having to modify the amp.

Converting from solid-state to valve rectification is impractical because you’ll have to install a new power transformer as well as another valve socket. Some builders simulate valve sag by soldering a ‘sag resistor’ between the output of a solid-state rectifier and the first filter capacitor.