Related Tags

Zane Carney’s 10 essential jazz albums every guitarist needs to hear

Fresh from releasing Alter Ego, a white-hot free jazz album that jives to the beat of LA’s late-night scene, Carney lists the jazz albums that changed him as a guitarist.

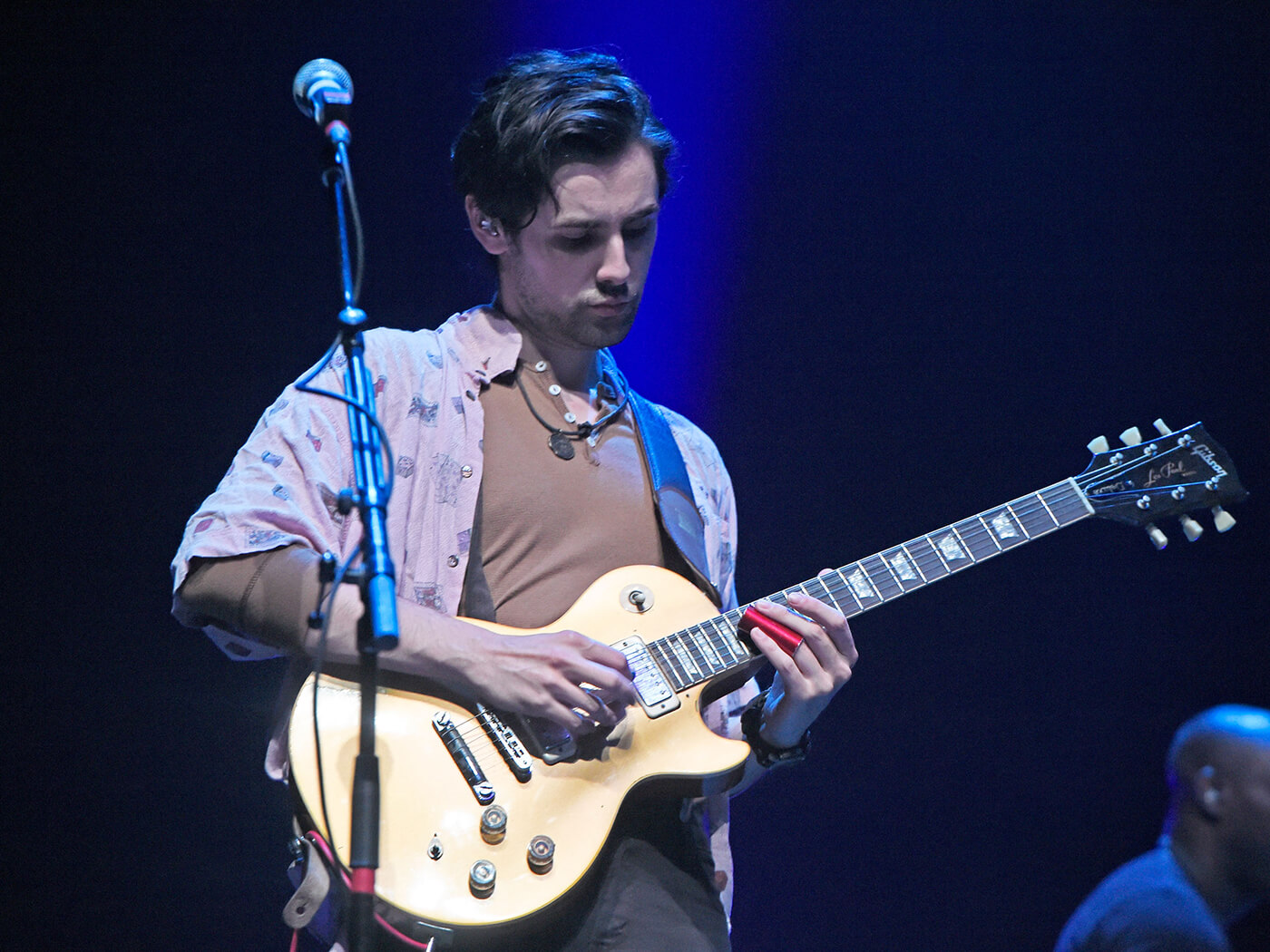

Zane Carney. Image: Stephen J. Cohen / Getty Images

I should say I started becoming a jazz player when I was 12 years old. But in truth, it feels like I’ve been one my whole life. And that is to say someone who enjoys improvising. Some people enjoy performing and perfecting. I enjoy discovering, especially with a band onstage. I just love that process.

The language of jazz is just such a vast expanse; it’s a genre of music where you get to draw inspiration and vocabulary from so many corners. For me, my journey began when I discovered a very specific artist that didn’t change my life, but uncovered it. His music revealed to me the life I was already living in my brain and it gave me language and a vocabulary for the way my brain worked. It truly changed my life.

When I first heard that artist, I remember tapping my mum on the shoulder and asking, “Why don’t you ever tell me about this guitarist?” And she said, “Well, honey, we don’t listen to jazz in this house.” I said, “Oh, well, this guy who I just heard, that’s how my brain thinks.” And I didn’t know there was a name for this. It was called jazz music. The name of that artist was Wes Montgomery, and one of his records, Smoking At The Half Note really began my transformation.

Something I believe strongly about – and which I’ve heard repeated by many different teachers – is that if you want to be a great jazz guitarist, don’t only listen to jazz guitar. Listen to jazz wind players. Because they’re playing melody lines that are just absurdly advanced. There may be a handful of truly legendary jazz guitar players, but there are dozens and dozens of legendary horn players, and they really know what they’re doing.

But we’re here for the jazz guitars, so without further ado… my ten essential jazz albums that every guitarist needs to hear.

Wes Montgomery – No Blues

Album: Smoking At The Half Note (1965)

Wes was probably the greatest jazz guitarist of all time by almost every metric, and on this album – and particularly on the song No Blues – he showed us how to apply jazz concepts onto a bluesy setting.

I discovered this album at a guitar camp I attended to as a kid. I remember a teacher there talking about diatonic harmony, the underlying language of Western music. He said, “For some of you who might want to listen to other genres [than rock or blues], you might want to listen to Wes Montgomery’s Smoking At The Half Note.” So I bought that album and when I put it on, it just clicked for me.

I was young and still learning the beginnings of the language. And all I knew was this first song, No Blues, had blues chord changes and yet sounded so different to me. Instead of the I-IV-V chord progression that’s in blues, I kept hearing other chords. I heard the I chord being major seven at times, I heard the VI chord, I heard the II and V, I heard tritone substitutions. I was like, “What are all these sounds?” I transcribed the solo when I was about 12 or 13. And it really unlocked me.

Joe Pass – Stompin’ At The Savoy

Album: Virtuoso! Live (1991)

The first time I heard this record was the first time I ever heard someone walk a bassline and play chords at the same time. I just didn’t think it was possible! I even thought he had recorded the chord and melody parts separately, but then I heard the audience applaud. Virtuoso! Live just shattered my idea of what was possible on the guitar, particularly in a solo guitar setting.

Joe’s playing really does stay with me – whether I’m doing a straight-up bebop gig or a solo guitar performance – I rely upon the things I learned when I transcribed his work. If you were to pick just one tune to transcribe off of Virtuoso! Live, I’d say do Stompin’ At The Savoy. There are some voicings on there that I still don’t hear guitar players use to this day: almost ukulele-esque voicings where you leave certain notes out of the formula and yet you still get the essence of the chord.

ScoLoHoFo – Brandyn

Album: Oh! (2003)

You might not have heard of this band, but you’ve probably heard of all the musicians on this record. ScoLoHoFo is an all-star jazz group featuring John Scofield on guitar, Joe Lovano on tenor sax, Dave Holland on upright bass and Al Foster on drums.

Here’s what I love about this record: there is no pianist, so that means the guitar is the only harmonic instrument on here. John Scofield is harmonising while playing melody, doing chord melody at a fast tempo and supporting the sax player all at the same time. His ears are wide open and his comping is really the hidden gem of this album.

I think a lot of guitar players think that our job is to just keep the rhythm, but in jazz, we want to be more nimble and agile than that. This album is a great exploration on how to comp as a guitar player.

Miles Okazaki – Straight, No Chaser

Album: Work (Vol. 1 to 6) (2018)

If you want to hear an album that truly shows the dedication it takes to be a jazz guitarist, it’s this one. I think Work may go down as one of the top ten jazz guitar albums of all time – it’s every single Thelonious Monk piece ever written, but played on solo jazz guitar.

Miles Okazaki takes Thelonius’ pieces and completely reinvents them. That to me is the jazz spirit, and something every jazz guitarist needs to embrace at some point. The track Straight, No Chaser is probably the most surprising one to hear, because it’s a melody that everyone knows, but I almost couldn’t recognise it the first time I heard it.

The album also exemplifies one of the core tenets of jazz: making decisions. Miles chose to remove elements from the original in his renditions, which is something we don’t do in jazz very often. Most of the time, we like to keep adding. I think it’s important to understand solo jazz guitar doesn’t mean I have to play a 13 add flat nine chord all the time. I can just do one note.

Django Reinhardt – All The Things You Are

Album: Djangology (1961)

Django Reinhardt’s music is such a 1930s jazz experience. What I love about these recordings is you can tell how they borrow from classical just as much as they do from Django’s own folk traditions. For this list, I would have to pick Django’s take on All The Things You Are off of the compilation album Djangology: it’s incredibly jazzy and just so romantic.

And plus, you get to hear a jazz violin! Which I think is a really important thing for guitar players to hear because it’s a cousin to guitar. Very few can play jazz violin convincingly, but Stéphane Grappelli of course does.

I also think a lot of shredders are going to be able to relate to Django’s sense of harmony, which oftentimes can take a straight-ahead approach à la classical music. If he’s on a dominant nine chord, he will arpeggiate a dominant nine chord, whereas other players from the 40s, 50s and 60s might play melodies focused on extensions. Because the harmony is much more consistent with what shredders are used to hearing, hot club jazz might be a great entryway for them into the wider world of jazz. And then one day, their ear will open up to Wes, maybe McCoy Tyner or even Philip Glass even.

Pat Martino – Oleo

Album: Live At Yoshi’s (2001)

There’s a whole resurgence of organ happening with neo-soul, pickup jazz and lo-fi beats. A lot of that influence stems from church music where the organ is the main instrument. So, if you truly want to be on the cutting edge of jazz, you need to learn how to play organ trio, and Pat Martino’s Live At Yoshi’s is a great example of how to do that.

Because an organ player takes care of the bassline while also playing densely harmonic stuff that sustains, it’s a whole different ball game than playing with a piano player. You have to learn how to deal with constant harmony. Thankfully, Pat Martino does this perfectly, and if you just transcribe Oleo, you’ll be giving yourself a real gift because this guy knows how to navigate the fretboard so nimbly, and in such a different way than someone like Django or Wes.

Mary Halvorson – Safety Orange, No. 59

Album: Away With You (2016)

Mary Halvorson’s compositions are a great example of knowing how improvising and having a deep well of influences can lead to new and inventive ideas. In Away With You, Mary arranges her compositions for an octet and does so beautifully.

Her playing basically goes, “Let’s break about 37 rules of what people think jazz guitar is supposed to sound like.” Not only would she draw from horn players, pianists, string players and guitarists, but classical music too: Schoenberg, 20th century, Stravinsky. And it’s just really inspiring.

Experimentalism is going to continue to be a part of jazz music, and I welcome that. There was a time where, if I brought a pedalboard to a jazz jam session at my college, I was frowned upon. Players would turn me away and say, “We’re doing a jazz thing.” And I just thought, “I just wish they would give me a chance. But you saw my pedalboard and thought that I couldn’t play.”

So I love that someone like Mary’s saying, “Hey, come on, these are new sounds. Is this not jazz? We are pioneers. Let’s go explore the new.”

David Torn – Only Sky

Album: Only Sky (2014)

Oftentimes as jazz guitarists, we get so excited about learning up-tempo bebop to prove we can play, or quoting obscure melodies to show we’re in the scene. But then David Torn introduced this album that basically went, “What if it’s not about impressing you, but about truly creating an emotional moment?”

This is a truly meditative album, and that’s the reason why I want to include it on this list of all things jazz guitar. My favourite players are the ones who can play 320 beats per minute if they want, but also really care about tone, really care about intention. Check out Torn’s compositions and the fact that he’s borrowing from jazz harmony to write them. And it does go both ways – if you studied classical or blues then you can learn to infuse that stuff into your jazz playing.

Pat Metheny – Missouri Uncompromised

Album: Bright Size Life (1976)

Finally an album everyone knows! Bright Size Life has possibly some of my favourite playing of Pat Metheny’s ever – and it has Jaco Pistorius on bass.

So here’s a conundrum: how do you play guitar when you have a virtuosic bass player? (Something I too have to do when I play with the Zane Carney quartet; Jerry Watts Jr. is a virtuoso). Well, check out this record and you’re good to go. Pat’s approach is just genius, pay attention to the way he treats Jaco as a horn and how he supports him as such.

And about that open sounding tone he has: when Pat Metheny came to speak at my college, he explained it was very important to him that his low string had the same tone as his top high string on the highest fret. He wants evenness. So he sets up his guitars that way, he’ll do unique string gauges and roll off his tone knob a certain way; even place different pickups in the bridge position to make sure it all balances out. That’s something that’s very important to him.

Jazz Futures – Mode For John

Album: Live In Concert (1993)

This is a rare one, but it’s so worth it. Jazz Futures’ Live In Concert was probably the second or third jazz record I ever bought. I must have been 12 or 13 when I picked it up. I remember my dad dropping me off at a place called Warehouse Records and me walking in to ask the counter, “Hey, do you guys sell jazz music?” and they were like, “Yeah, in this one area in the back.”

So I found this record, and it’s ridiculous how accurate the name Jazz Futures is. Allow me to list off the members of this band: Marlon Jordan and the late Roy Hargrove on trumpets, Antonio Hart and Tim Warfield on alto sax, Mark Whitfield on guitar, Benny Green on piano, Christian McBride on upright bass and Carl Allen on drums. That’s a serious all-star band, and what’s great is that on this record, many of those guys were just 19 to 23 at the time they made this recording.

I listened to this record so much as a kid that I can sing every solo on record. It was my introduction to heavy-hitting, up-tempo modal jazz. Mark Whitfield is really into alternate picking, and so he’ll just pick his way through the changes in high octane fashion. It’s loud and proud and strong and I think it’s important for guitarists to embrace that. We don’t have to be dainty jazz guys and just roll the tone knob down – just get in there man!

– As told to Daniel Seah

Zane Carney’s Alter Ego is available on all major streaming services now. Pick up a digital copy at orendarecords.bandcamp.com.