Related Tags

All About… Dick Denney

Dartford in Kent can lay claim to making two lasting and profound contributions to guitar music: The Rolling Stones and Vox amplifiers. We profile the man who helped power the pop…

The man who many regard as the UK’s most important guitar amp designer was actually deaf in one ear, but Dick Denney’s perforated eardrum may have been the making of him. As a result of his affliction, he was exempted from military service during World War Two and seconded to the Vickers munitions factory – something that would permanently alter the trajectory of his life.

During the pre-war years, Dick had become infatuated with both jazz music and radio electronics. Early experiments resulted in the inevitable destruction of the family radio, but Dick’s skills improved and his wages from the factory enabled him to buy components. His work at Vickers also meant that Dick was freed from an unwanted apprenticeship in his father’s barber shop, and perhaps most importantly of all, it introduced him to a man named Tom Jennings.

During the war, amateur radio activity was prohibited so, as a guitarist, Dick turned his electronic skills to amplifier building. His goal was to develop an amplifier that was loud, but also small and light – and he had ample opportunity to test them out.

Munitions factories were understandably a choice target for the Luftwaffe’s bombing attacks, and a as a result, the staff at Vickers spent extended periods sheltering during air raids. Entertainment was in short supply down in the shelters, and so to keep up morale, Dick, Tom Jennings and a few other members of the workforce would put on musical performances – these performances with Jennings gave Dick a chance to test and refine his amp designs.

Planning ahead

Jennings was clearly impressed with what Dick had produced, and being of an entrepreneurial mind, discussed a joint venture with Denny where they’d produce amplifiers for organs and accordions together. However, nothing ever came of the plan, and after the end of the war, the pair went their separate ways and lost contact.

By 1951 Jennings was running the fairly successful Jennings Organ Company, but it soon become apparent that diversification was necessary to grow the business. He also owned a music shop and would notice growing interest in guitars during the early rock ’n’ roll years.

Since there were very few guitar amps available in the UK, and becoming an importer for American Gibson and Fender amps wasn’t viable, Jennings tried to adapt one of his organ amplifiers for guitar. It proved unsuccessful, and the project was shelved.

Meanwhile Dick Denney had set up in business as an electronics and radio repairer, while moonlighting as a busy dance band guitarist. However, in 1952 he suffered a collapsed lung and was forced to take time off to recuperate.

Dick kept busy by resuming work on guitar amps and by 1955 his efforts had culminated in a 6V6-driven 15-watt combo amp with a single 12-inch speaker. The following year he added a Wurlitzer-inspired vibrato circuit, with a mod that provided tremolo, too.

Unfortunately, Dick��’s amp was prone to noise due to the octal preamp valves he was using. A re-design using EF86, ECC83 and EL84 valves solved the noise issues while retaining the tone.

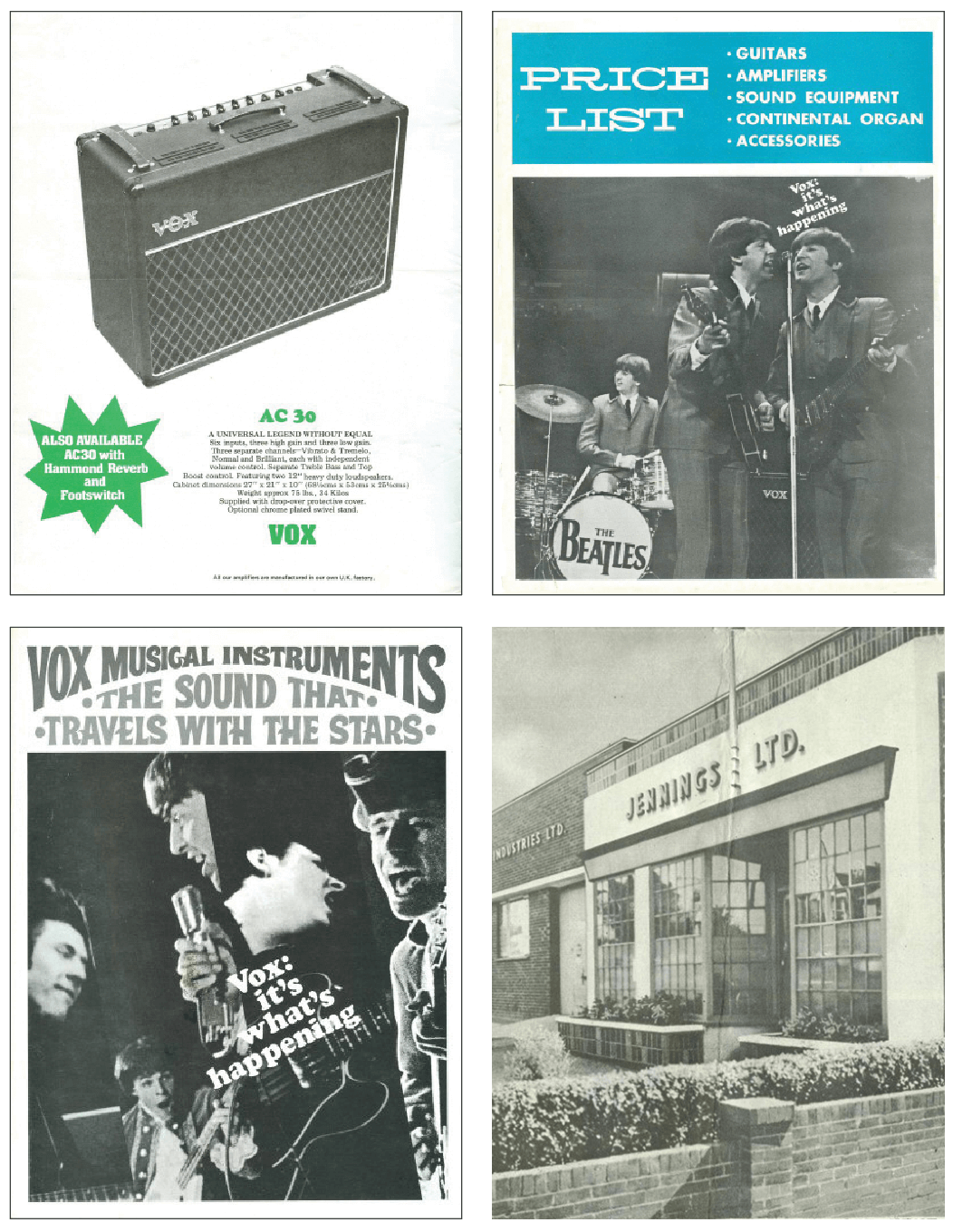

Dick first built two of these redesigned amps – one for himself and another for his a colleague. Suitably impressed by his friend’s creation, that colleague decided there might be a wider audience for it – as providence would have it, he decided to take the amp in to Tom Jennings’ shop to see if he was interested in ordering a couple. Jennings soon realised who it was who’d built the amp, and two days later he called at Dick’s house to offer him a job. Jennings Musical Industries (JMI) was formed in 1957 to put Dick’s amplifier into full production under the brand name Vox.

Finding his feet

While the original amp was a good first step, much redevelopment work was needed on his design before it would be ready for the public. But by the end of January 1958, the first Vox amp was ready and they called it the AC1/15, later shortened to AC15.

The AC15 caught on fast, with top stars of the day such as The Shadows soon using them. But while 15 watts may have been sufficient for dance bands, the newer rock ‘n’ rollers needed more volume – if only to hear themselves over screaming fans. Vox introduced two more amps in late 1958 – the AC4 and AC10 – but that was a move in the wrong direction for the bigger outfits.

The Shadows had tried a 60-watt Fender Twin on Charring Cross Road, and while they were impressed with the volume, they preferred the smoother and richer Vox tone with its softer overdrive characteristics. They suggested a ‘twin AC15’ but Jennings was reluctant.

In the BBC documentary Vox Pop, former JMI engineer Rodney Angell recalls how Dick’s proposal for a doubled up AC15 was dismissed by Jennings as being “too heavy, too loud, too big” and that Dick should “go away and forget about it”.

But Dick knew that he was onto something, and recognising EL84 valves, cathode biasing and an absence of negative feedback as the key ingredients of the Vox tone, Dick started building some twin versions of the AC15 for The Shadows without Jennings’ approval or knowledge. He wouldn’t keep it quiet for long, however – Jennings spotted the extra parts orders, and furiously summoned Dick into his office. And a proper row ensued, but Dick walked out with permission to build 10 more after Jennings told him “on your head be it”.

The rest, as they say, is history. The Shadows took delivery of their first three units of what was christened the AC30 in late 1959, and within a few years it would go on to power the biggest band of all time, The Beatles. Some even consider the AC30 to be the greatest guitar amp of all – and without Dick Denny’s persistence and conviction, it might never have even been made.

Big boost

The early AC30/4 had four inputs and an EF86 pentode preamp, but the EF86 was a bit too delicate for high volume duties. The preamp was re-designed with a more robust ECC83 dual triode, which allowed for an extra channel and six inputs. Introduced in 1960, this version is called the AC30/6.

Inevitably the AC30/6 sounded different because it had less gain, sensitivity and clarity. Customers complained their Strats didn’t sound like The Shadows’ records, so Vox tried a stopgap solution with a specialised lead guitar version called the AC30/6 Treble – but Dick knew that something more was needed.

Dick and his team devised an add-on module built on an L-shaped metal assembly with an ECC83 valve, plus treble and bass controls. In addition to wider tone variation and extra treble, this ‘Top Boost’ module made up the missing gain.

Although it has been said that Dick was emulating late 50s Fender tweeds, the Top Boost is actually an exact copy of the Gibson GA70 tonestack – complete with the directly grounded bass pot that many consider to be a design error.

The AC30/6 could also be ordered with the module pre-installed and it’s this AC30 that can be heard on the early Beatles records. Many regard the AC30/6 Top Boost as the ultimate version, but of late, opinion has begun shifting back towards non-top boost AC30s.

Testing the waters

Although best known for amp and effect electronics, Dick then turned his hand to one of Vox’s most unusual and innovative products – the Guitar Organ. It was his idea to combine the mechanical parts from a Phantom guitar with the oscillators from a Vox Continental. A three-way selector provided regular electric guitar sounds, organ sounds that were triggered merely by holding down the strings and a combination of both.

The neck contained multiple wires connected to the frets and it could be used with a special electronic pick to play arpeggios. It could even generate rhythms, but the instrument was extremely heavy, quite expensive and, due to early manufacturing issues, acquired a reputation for unreliability.

Despite Vox’s reputation for crystalline clean sounds, Dick can also lay claim to being one of the pioneers of something altogether more dirty: fuzz. He claimed to have designed an early fuzz circuit with two Mullard OC77 germanium transistors, something that’s later substantiated by Paul James of Vox’s advertising department, who remembers the prototype being built into an OXO cube tin. Dick was convinced fuzz would sell, but the ever-sceptical Tom Jennings hated the sound, and vetoed the project.

Vox would get into the fuzz game of course, with its Italian-made take on the legendary Tone Bender – some have even suggested it was Dick’s work. Dick himself claimed to have given the Beatles a prototype Vox Tone Bender in 1965 that was used on Rubber Soul. Vox announced the 816 Distortion Booster in 1965 and launched it in 1966. For a time, Brian May had one built into his guitar and Dick would go on to design a fuzz pedal for Colorsound.

Dick also designed the Vox Echo-Machine and a wireless microphone, but through the mid 1960s there were many changes at Vox.

Vox populi

When Tom Jennings resigned from the company in September 1967, Dick followed soon after. He continued working for various clients but it’s fair to say that Dick’s most important work had already been completed by 1965.

Dick’s granddaughter Emily Turner recalls how “he toured the world demonstrating Vox equipment’, sometimes on American TV. He also set up equipment for The Beatles and The Rolling Stones at important shows. Apparently, Dick “was fond of The Beatles and enjoyed banter with John Lennon who called him ‘nanny goat’ because of his beard”.

Fans once mistook him for a Beatle and tore some of his clothes. They clearly didn’t notice the cosy cardigan Dick habitually wore, or his trad-jazz goatee. He also came to The Beatles’ rescue at a Scarborough gig when some amps on trolley stands started trundling down the sloping stage towards them. Thereafter, they were fitted with braking casters.

The Facebook page set up in his honour reveals that “Dick was warm, funny and passionate about music”. In later years, he set up an eight-track studio in his dining room where he recorded all his grandchildren singing along to Blue Moon.

Apparently, Dick’s house was chock full of electronic components and circuit boards and his garage was packed with “bits that might come in useful”. He called everybody ‘Cuz’ and enjoyed Blue Nun or a good port topped off with a cigar.

Although he never became rich, Dick felt content that he had made a living being paid for what was essentially his hobby and that’s possibly the nub of it. He combined a working knowledge of electronics with a musician’s sensibility and great ears to achieve the sounds he liked using the technology and components of the time.

That countless guitarists have appreciated Dick’s amplifiers is testament to his skill and judgment. The same cannot be said for many highly trained electronics engineers working in the same field. Dick died a few months after his 80th birthday on 6 June 2001, leaving a son, five daughters and the most wonderful sonic legacy.