Related Tags

The history of guitars with built-in tech

Charting the rise, fall and rehabilitation of gadget guitars

The first time someone tried fitting fancy gadgetry to a guitar, it unleashed terrifying satanic forces upon the world and turned a whole generation into gibbering delinquents. In other words, it was a wonderful success. So can you blame people for spending the best part of a century trying to match it?

- READ MORE: The history of the Epiphone Casino

That first gadget was, of course, the electro-magnetic pickup – a little innovation that, after a few decades of tweaks, was powerful enough to turn the gently strummy six-string into the driving force of that ungodly phenomenon known as rock ’n’ roll. Not a bad starting point for our history of guitars with built-in technological enhancements.

This, though, is a story with a lot more misses than hits. You might well look at the new Boss Eurus GS-1 – packing an advanced polyphonic synth engine into what otherwise looks like a fairly traditional two-pickup S-type – and speculate that its odds of globe-straddling success are perhaps on the long side. But there is some evidence to suggest that us plank-janglers aren’t quite as conservative as we sometimes think we are…

come in the past few decades

Are trends electric?

First up, we ought to nail down our definition of ‘tech’. If it’s alright with you, we’ll focus on the electrical and electronic – otherwise half of this feature would be a list of whammy bars.

So we won’t be dwelling on Doc Kauffman’s pioneering vibrato system of 1929, nor on single-string pitch-changers like the B-Bender, nor even the barmiest-looking doohickey ever screwed to the face of a musical instrument: the Rickenbacker ‘comb’ of 1966, for switching between 12-string and six-string formats by physically pulling half of the strings out of the way.

If we narrow things down further to exclude gadgets that are essentially useless, that rules out another Rickenbacker idea: the 331 Light Show model of the early 70s, whose clear top covered an array of coloured lamps that glowed in sync with its output. Think that’s daft? Don’t tell Matt Bellamy – one of his Manson ‘Mattocaster’ guitars is fitted with lasers that respond to playing dynamics in the same way. Mind you, it’s said to weigh a ton and he hasn’t gigged it since 2007.

Lights don’t have to be purely cosmetic, though. Various companies today are making LED fret markers to aid navigation on dark stages, while the Fretlight teaching system involves embedded LEDs that show novices where to put their fingers. It’s not world-changing, but it’s clever.

Anyway, whammies aside, this is all peripheral stuff. It’s time to turn our attention to what most guitarists are really interested in: drowning out the drummer.

Amp pain supernova

The most obvious piece of technology to build into a guitar is an amplifier. That way you don’t need… well, an amplifier. And it’s something that several makers tried in that most fearlessly forward-thinking of decades, the 1960s.

Höfner seems to have got there first with the Fledermausgitarre (‘bat guitar’) that it created for the 1960 Musikmesse expo: an odd-shaped beast with a four-watt solid-state amp built into the top part of its body.

It never went into full production – probably because the amp and its motorcycle battery made it too heavy to play – but another European pioneer, Antonio ‘Wandre’ Pioli, took the concept further with his Bikini model, made in Italy by the Davoli Krundaal company for at least two years in the early 60s. This had an 1×8” transistor combo in a separate pod bolted to the main body… and also included a jack output for plugging into a proper amp, just in case.

early tech-toting guitars didn’t so much blaze a trail as whack a few nettles with a walking stick

The Japanese weren’t far behind with the Teisco TRG-1 of 1964, which improved on its predecessors by actually looking like a guitar, but what do all these amped-up creations have in common? To put it bluntly, they all died on their arses. Rory Gallagher used a TRG-1 on some of his last recordings, and Ace Frehley of Kiss was pictured with a Bikini in the early 80s (even if we’re not sure he ever played it), but the practicalities of weight and power supply ensured this idea never really caught on.

Vox’s bid to revive the idea with its 2011 Apache range of travel guitars was not successful; but in the current age of mini-amps and super-efficient batteries, you do have some all-in-one options. These include the hi-tech Fusion Guitar, ElectroPhonic Innovations instruments with built-in stereo speakers and effects, the kid-friendly Loog Pro VI Electric and – from a brand with serious pedigree in portable amplification – the Pignose PGG-200.

But let’s be realistic. What we’re looking at here is a clutch of niche tools designed for fun, travel, maybe a bit of busking. Installing an amp in a serious guitar for gigging or recording just doesn’t make a lot of sense in the modern world.

Scale it down to just effects, however, and things suddenly get a lot more lively.

I wanna effects you up

It’s time for another definition. What are effects? For our purposes, they’re sonic manipulators that do more than just filtering, boosting or switching. So the Vari-tone dial on the 1959 Gibson ES-345, the active circuitry inside the 1963 Burns TR2, the Orgeltone spring-loaded volume control fitted to the 1965 Framus Strato, the middle and treble boosters hidden in the 1983 Fender Elite Stratocaster – they don’t count.

Besides, Doc Kauffman got there before all of them: he produced a motorised version of his vibrola for Rickenbacker in 1937. That must surely be the first ever onboard effect – only slightly undermined by the fact that it required mains power to operate.

Our next candidate is the Epiphone Professional from 1962… and it’s immediately disqualified for cheating. This elegant semi-acoustic had reverb and tremolo controls on its giant butterfly-shaped pickguard, but the effects themselves were actually found in the 35-watt amp it had to be plugged into (via a special cable) in order to work properly.

For true onboard effects, you’d have to wait until 1966-67, a period that saw the launch of another bold effort from Höfner along with a quartet of them from Vox. Hofner’s 459VTZ was a close relative of Paul McCartney’s famous violin bass, but this six-string had built-in fuzz and tremolo circuits – the same pairing found, along with a range of boosts, in Vox’s Mark VI Special, Phantom VI Special and 12-string Phantom XII Special, plus the Mosrite-style V262 Invader.

Ian Curtis can be seen strumming on a white Phantom VI Special in the video for Love Will Tear Us Apart, but the Invader was surely the pick of this bunch – as well as being the prettiest, it also included a wah effect operated by pushing down on a lever behind the bridge.

So, what is the legacy of these tech-toting trailblazers? In truth, they didn’t so much blaze a trail as whack a few nettles out of the way with a walking stick. That is to say that others followed, but not in huge numbers.

Univox was one of the first with the Effector (also sold under the Kay brand), an LP-shaped solidbody with fuzz, two kinds of tremolo and two phasing effects, all powered by a single nine-volt battery. Then came the Gretsch Chet Atkins 7680 Super Axe of 1977, whose expansive body hid a phaser and a compressor. The Japanese-made Electra MPC range of the same era offered modular effects that clipped into the back of the body; and even the Soviets joined in with the Formanta (aka Borisov) Solo-2, which had a fuzz circuit and looked like a Fisher-Price Jazzmaster.

Rickenbacker jumps back into our story in 1988 with a compressor-equipped Roger McGuinn signature model, the 370/12RM, while Fender had a bash at the end of the 80s with its distortion-equipped Heartfield RR9. But there then followed a lean spell through the bone-dry grunge era of the 90s… and by the time we next saw a notable guitar with effects, in 2001, the idea had become retro. This was the Danelectro Innuendo, with distortion, chorus, tremolo and echo circuits engaged via little push-buttons on the control panel. It was a fun instrument, but with a whiff of ‘novelty’.

Again, though, the principle lives on. Remember Matt Bellamy’s lasers? There’s nothing so frivolous about the tech built into some of his other Mansons, including a Korg Kaoss Pad and versions of the Zvex Wah Probe and Fuzz Factory. He’s also been known to use a kill-button – alright, we’ve already said a switch doesn’t count as an effect – and both the Fernandes Sustainer and Sustainiac systems for generating infinite notes through an internal feedback loop.

Then there’s the rotary-style LesLee circuit offered on some German-made Deimel guitars, while US boutique maker Bilt offers a Relevator + Effects model with fuzz and delay (the signature version it created for Sarah Lipstate in 2019 adds modulated reverb). And just this summer, British brand Fidelity unveiled a one-off dB Baritone with an innovative whammy-controlled fuzz feedback circuit.

Oh, and Bellamy’s not done yet. Here’s what he said after becoming the majority shareholder in Manson Guitar Works in 2019: “We’ll certainly be exploring enhanced electronic features to further evolve the guitar into the modern era.” There’s already been talk of a model with a built-in DigiTech Whammy – watch this space.

the soundtrack for the 1982 action film Death Wish II

Living in a Vox

Of course, those “enhanced electronic features” needn’t be limited to effects, and that brings us to the wildest projects in the history of Franken-luthiery: guitars that aren’t even guitars. Again we’re in the realm of things that seemed like a good idea in the 60s; but again it’s clear the wider concept never truly died.

Somewhere on YouTube there’s a clip of Dick Denney, the man behind the Vox AC15 and AC30, appearing on an American panel show in the mid-60s. But he’s not showing the celebrity guests a new amplifier. Complete with rakish goatee beard and incongruous Kent accent, Dick is there to demonstrate the Vox V251 Guitar Organ.

First presented to Lennon and McCartney in 1964, the Guitar Organ was based on the same Phantom body as those later effects-laden Special models. But this was really a Vox Continental organ in disguise: each fret was a six-part electrical contact, and pressing a string down to touch one completed a circuit to generate the note.

Denney briefly demonstrates its hybrid mode to impressive effect in that video, playing an organ melody with his left hand while strumming guitar chords with his right. Guess what, though? The Guitar Organ was too heavy and too complicated (just imagine how many wires there must have been running through the neck!), The Beatles didn’t like it and it fizzled out in 1967.

There were more glorious failures – notably the Italian-made Godwin Guitar Organ of the mid-70s, which followed the Vox template but added way more switches; and the 1976 Hagstrom Swede Patch 2000, marketed as the first guitar synthesiser. A collaboration with Ampeg, this one again turned the frets into electric contacts but needed an external synth to generate the sounds. It didn’t survive into the 80s.

Synthy irresistible

Pausing briefly to doff our cap at one more 70s oddity, the Guyatone LG-23R with its crude built-in drum machine, we now arrive at the heyday of keyboard-based pop… and various synth makers’ attempts to drag guitarists into this gleaming, shoulder-padded future.

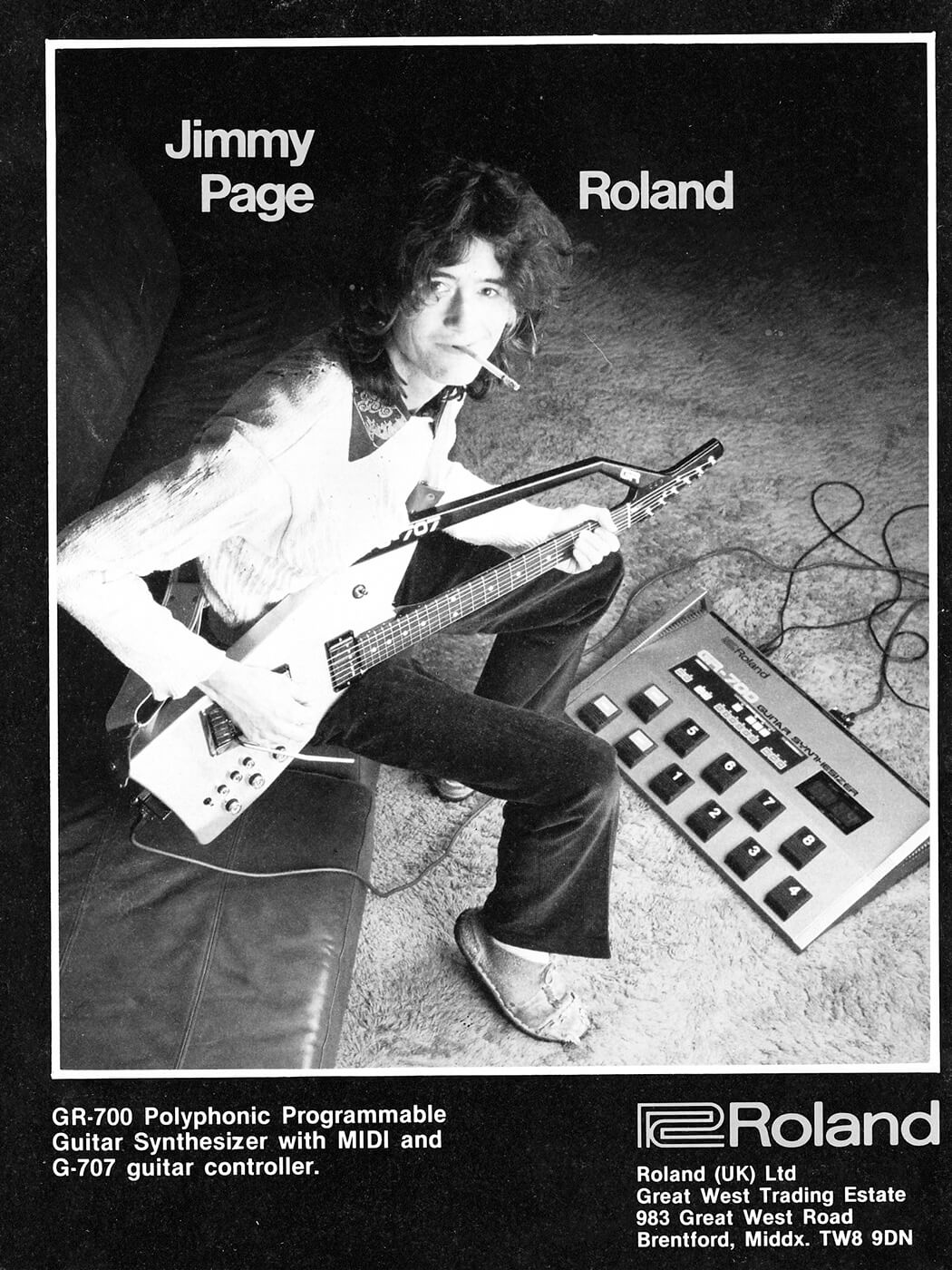

Roland launched a series of analogue guitar synths beginning in 1977 with the GR-500. Like the Hagstrom, this was just a controller rather than a standalone sound-maker; even so, by the time the futuristic G-707 model came out in 1984, Roland’s roll-call of users had expanded from obvious boundary-pushers such as Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew to include Andy Summers and even Jimmy Page.

Casio and Yamaha wanted a piece of this action, spurred on by the arrival of MIDI in 1983, and their various offerings were joined in 1985 by a distinctly unconventional British effort: the SynthAxe. But the tech still wasn’t streamlined enough to make self-contained synth guitars viable… even if another maker from these islands, Stepp, gave it a go in 1986 with its DG-1 – a device now remembered mostly for being the ugliest musical instrument ever made.

ROLand’s roster of GUITAR SYNTH users included robert fripp, adrian belew, Andy Summers AND Jimmy Page

Casio finally came up with a genuine hybrid in 1988, the PG-380. This was a proper guitar – Strat-style body shape, two single-coils and a humbucker, Floyd Rose licensed bridge – but with an actual synth inside, triggered by a hexaphonic pickup and controlled by a panel of buttons and a two-digit display. By all accounts it was pretty decent; the only snag was that almost nobody wanted one.

Roland eventually scaled back its ambitions to designing hex pickups that could be fitted to just about any six-string, making the conversion from guitar to synth easy and, best of all, reversible. It’s still selling those GK pickups to this day, along with a GR-55 processor to plug them into.

Which brings us neatly back to that new beast from Roland’s guitar-centric division, Boss. The Eurus GS-1 revives the self-contained concept by taking advantage of the fact that synthesiser tech these days is way more powerful, and way smaller, than it was in the 80s. Like the Casio PG-380, the GS-1 can also be played as a regular guitar; unlike the Casio, it offers deep editing of its synth sounds via a dedicated smartphone app. Whether that means it’s destined to take over the world is not yet clear, but it certainly has a better shot than any of its clunky predecessors.

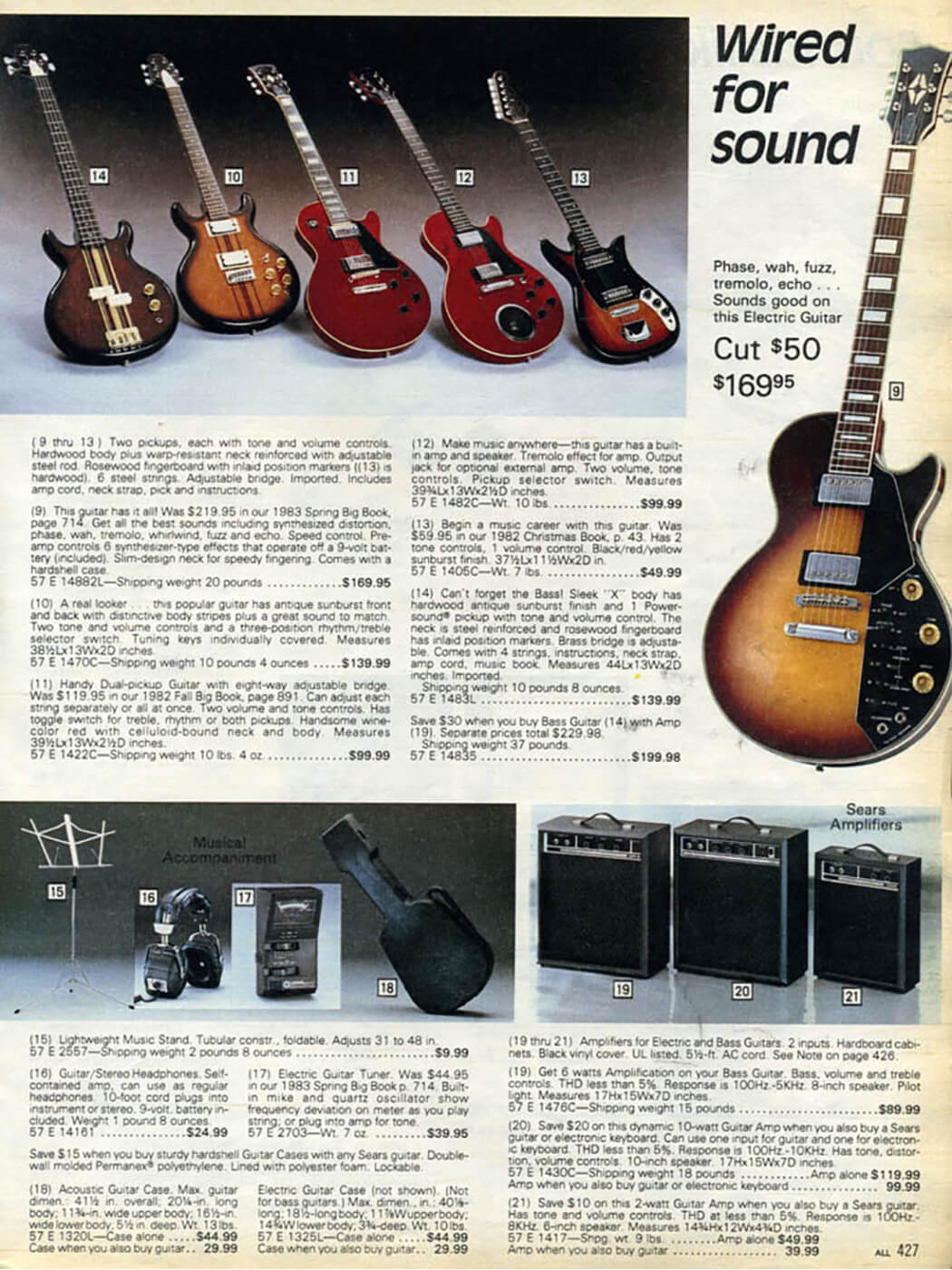

sold through the Sears catalogue

Lovin’ the future

There’s one category we haven’t touched on yet: the guitar that doesn’t try to sound like an organ or a violin or a Stormtrooper’s alarm clock, just some other guitars. Incredibly, it’s now almost two decades since Line 6 released its first Variax, digitally modelling different tones in such a way that you could flip from a Telecaster to a dreadnought (or a banjo) with the twist of a rotary switch.

Not everyone was immediately won over by the Variax, but it’s still going strong and currently comes in seven different flavours, including a couple of hard-rocking Shuriken models. It’s been a success because, for all its technological complexity, it still looks and feels like an electric guitar – and a fairly low-key one at that.

The same can’t be said of – sorry, we had to mention it – the Gibson Firebird X. Launched in 2011, this modelling monster was the culmination of a whole digital programme for Gibson, beginning with the string-splitting HD.6X-Pro in 2006. The reaction to the X was fiercely negative, sales were non-existent, and a now-infamous leaked video of unsold guitars being crushed by a bulldozer provided a fitting end to the company’s futuristic adventure. In fact, it had soon abandoned even the Firebird X’s least offensive techy feature: robot tuners, fitted to most electric models across the 2015 range but gone completely by 2019.

Then there was Moog – a name inextricably linked with synthesis which had collaborated with Gibson back in the late 1970s on the RD range of instruments equipped with active preamps and compression and expansion circuits. A Moog-branded guitar arrived decades later in 2008 and even scooped Best In Show at Summer NAMM. But its innovative blend of sustain and filtering tech failed to capture the mainstream imagination and the Moog Guitar was later discontinued.

For the future of digital luthiery, then, the signs are mixed. Likewise, there surely will be more offerings with onboard effects, and perhaps headphone amps. But there’s one very good reason not to expect a full-blown revolution in this field any time soon.

While continuing improvements in battery tech mean the issue of powering these circuits is less problematic than it used to be, one other snag remains: turning them on and off. Until someone invents the three-handed guitarist, stompboxes will surely remain the most practical way for most players to enhance, mutate and pulverise the voice of the electric guitar – and that’s just fine by us.