Related Tags

How the abuse and misuse of guitar gear drove rock music’s evolution

From slicing speaker cones with razorblades to turning guitars into splinters in a collision of angst and art, rule-breaking was central to many of the great leaps forward in pop history.

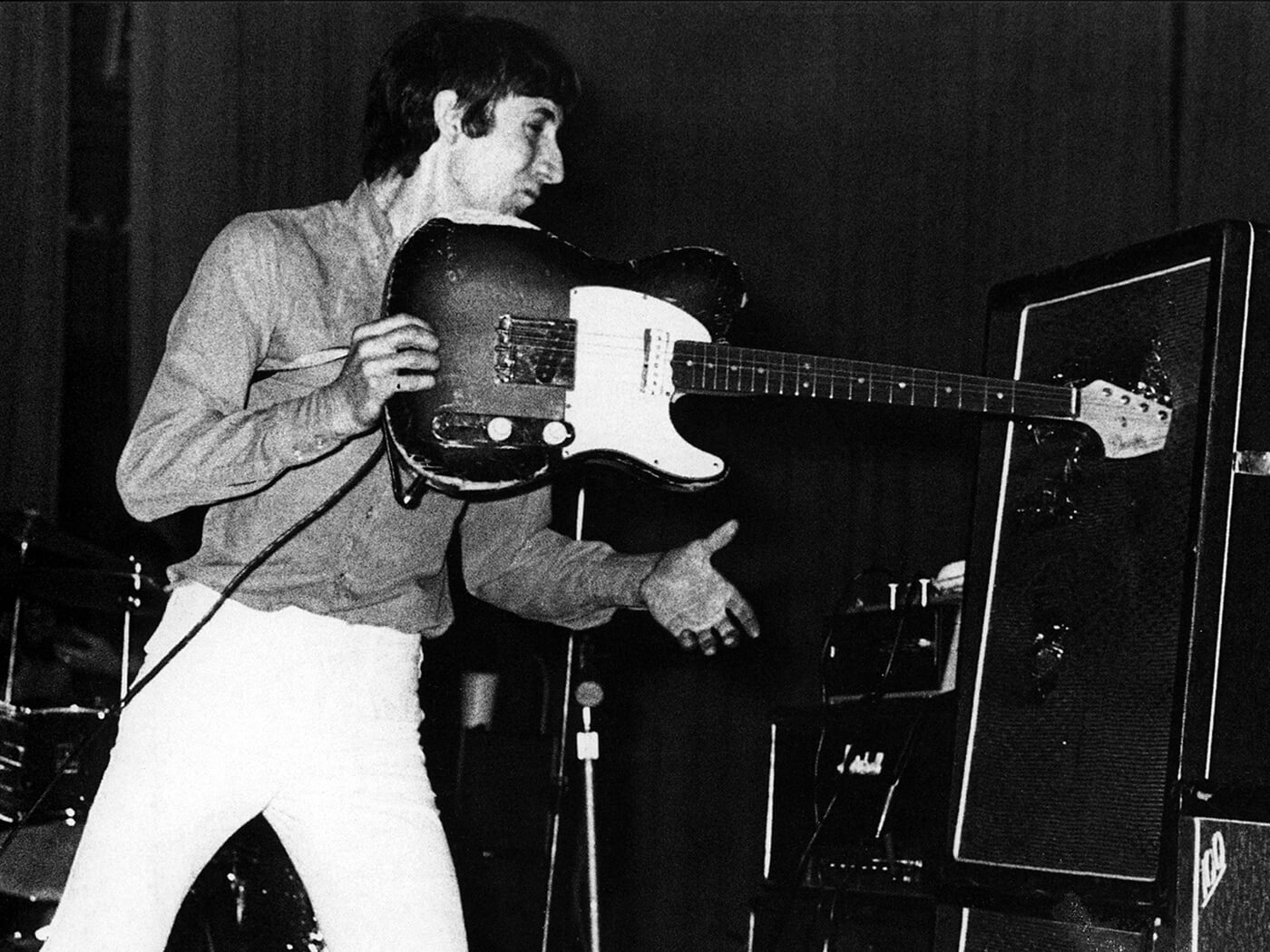

Pete Townshend performing live onstage with The Who in Jaguar Club on 10th April 1967, smashing his Fender Telecaster guitar into amplifier. Image: Chris Morphet / Redferns

There are those who look after their instruments and gear with great care, nervous of even the slightest ding or blemish. And then there are players who are willing to chop and change and knock their stuff about, just to see what happens. This is the group we’re interested in here: the musicians who misuse and abuse gear. And some of them, as we’ll see, have changed the course of popular music in the process.

Poor sound? No, inspired sound!

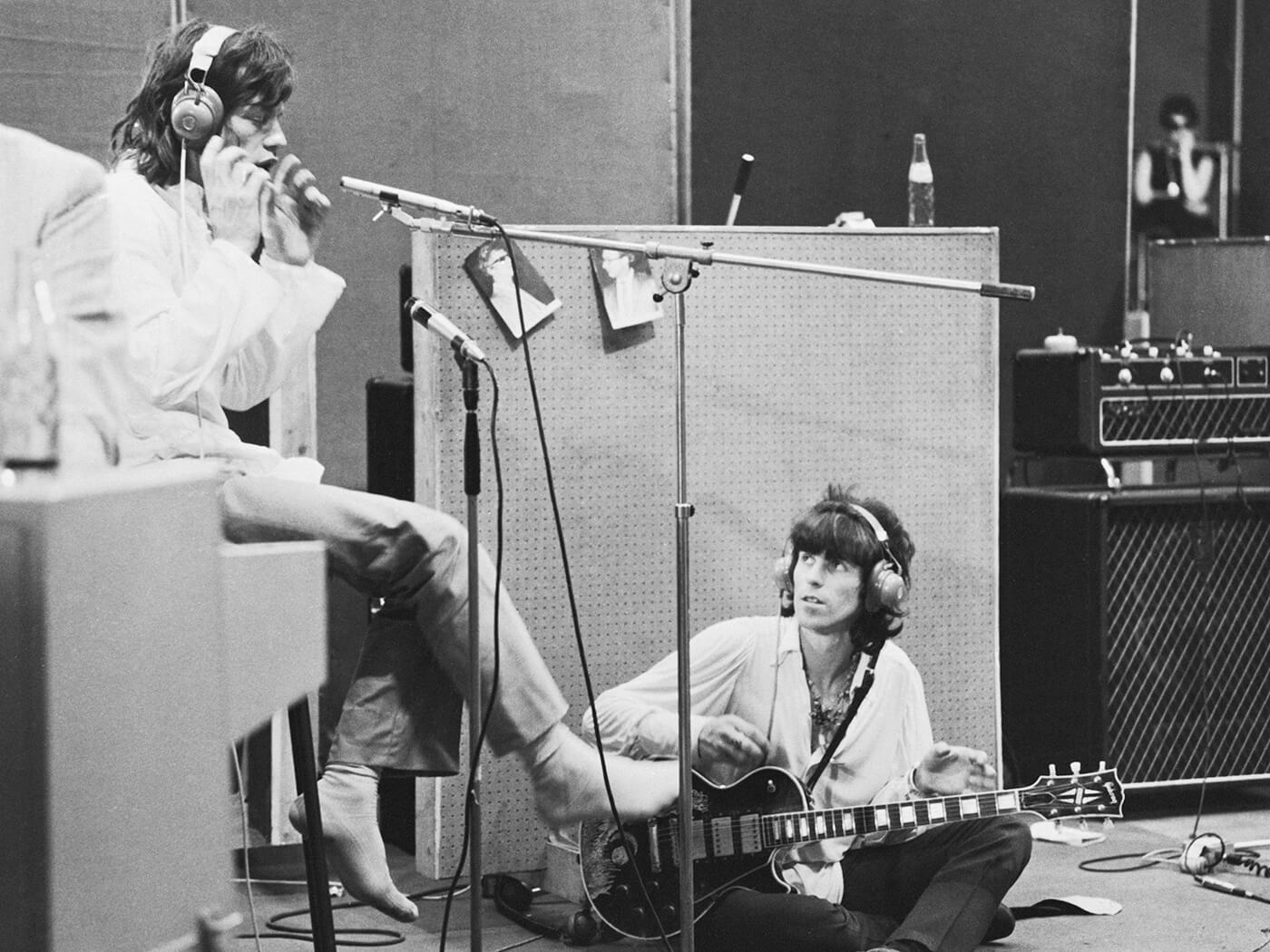

By 1968, Keith Richards was regularly using a small portable Phillips cassette recorder to capture song ideas when he was out and about in dressing rooms, hotels, and anywhere else that inspiration might strike. Gradually, he began to find that he liked the sound that this relatively crude recorder gave to his random demos, especially to the acoustic guitar he’d often be strumming so that he could remember a chord sequence or a melody idea that otherwise might go missing.

As the recording sessions began for the group’s next album, which would become Beggars Banquet, Keith suggested to producer Jimmy Miller that they might be able to transfer one of his rough Phillips recordings to the studio recorder at Olympic studio in London. The crunchy jangle of his acoustics created a remarkable backbone throughout Street Fighting Man, one of the standouts of the album – and a firm reminder that sound quality is a relative notion.

Ignore the name on the box

Imagine it’s early in 1951. Take a look at this new amp, just introduced by Fender, poking out 26 watts with a single 15-inch speaker. When guitarist Willie Kizart got his, he’d peered at the plate on the front, which said ‘Bassman’. He chose to ignore that once he’d plugged in. What a sound! This was clearly a great guitar amp.

Later, Willie was in something of a panic. He’d just arrived at Sam Phillips’s studio in Memphis, and somehow the amp had fallen off his car’s roof rack. He took it inside, plugged it in – and something wasn’t right. The sound was fuzzy, distorted. Someone suggested one of the tubes might have blown.

There was no time to repair it. Willie and the rest of Ike Turner’s band, known for this session as Jackie Brenston & His Delta Cats, proceeded to cut five songs, including a prototype rock ’n’ roll A-side, Rocket 88. Willie’s fuzzed-out guitar riffs powered it along with a sound that marked the debut of deliberate distortion – and all because of some accidental abuse of a new Fender amp.

Again – only backwards?

Today there are plugins that can do it, but creating backwards guitar was a technique that first began to turn up in the 60s. Nobody did it quite so well as Jimi Hendrix for the solo on the title track of the Are You Experienced album, although George Harrison had beaten him to it with the brilliantly conceived solo on I’m Only Sleeping, recorded in early 1966.

Jimi was, of course, always looking for new sounds and textures and effects. But when he decided he wanted to have a backwards-playing guitar for this solo, it must have caused a few scratched heads at Olympic studio in 1967. It took a concerted effort to work out what you wanted to hear in reverse and then record it ‘forwards’ against a flipped multitrack running backwards.

Jimi worked out his part carefully, paying careful attention to the way the shape of the notes change when they’re reversed. Then he had a go at recording the part against the backwards-running tape – which would then be played back in the regular direction. The guitar part Jimi added would now sound ‘backwards’ against the regular track. Got that? It’s difficult enough to get a sober head around the concept, let alone one that might have indulged in any chemical alterations.

Don’t be afraid to smash it up

Looking back on the smashing 60s, Pete Townshend said once that he sometimes felt very bad about wrecking particularly good guitars, excusing himself by explaining that often when he took a swing with an unfortunate axe, he was working with “production-line instruments”. There are pictures of him taking it out on Strats, but most famous is a snap of him sitting sulkily at home with a backdrop of dismembered Rickenbackers.

Apparently it all began in summer ’64 at Pete’s band’s regular gig at the Railway Hotel pub in west London. It was here that he first smashed his guitar into the ceiling above the stage – possibly by accident, possibly by design. But he sensed a good audience reaction, and he and the group continued into further destructive routines.

It didn’t hurt when Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp came to see the group there with a film appearance in mind. But once they saw what was going on, they decided to manage them instead. Smashing a guitar might seem the ultimate act of guitar abuse and a senseless act of destruction to most of us, but it didn’t do The Who’s career any harm at all.

Accept the unacceptable

Fred Frith was the guitarist in the English art-rock band Henry Cow, at turns a melodic, noisy, and rambunctiously avant-garde outfit. He played a sunburst ES-345, Varitone dismissed and with a removable pickup mounted at the nut-end of the neck.

When Fred made his Guitar Solos album in 1974, he went even further out. For some pieces he developed the idea of the prepared guitar, based on the prepared pianos of avant-garde composer John Cage, who would place objects such as cutlery and screws between the strings to alter their sound. Fred applied these ideas to his guitar, using alligator clips, sticks, springs, and pieces of metal or glass, creating an un-guitarlike array of sounds and tones.

Until recently, Fred taught in the music department at Mills College in Oakland, California, which he described as an institution renowned for decades as the epicentre of the American experimental music tradition. If you’re interested in preparing your own guitar, you might also want to investigate the work of players such as Derek Bailey and Glenn Branca. It’s guitar, Fred, but not as we know it.

Fiddle with your knobs

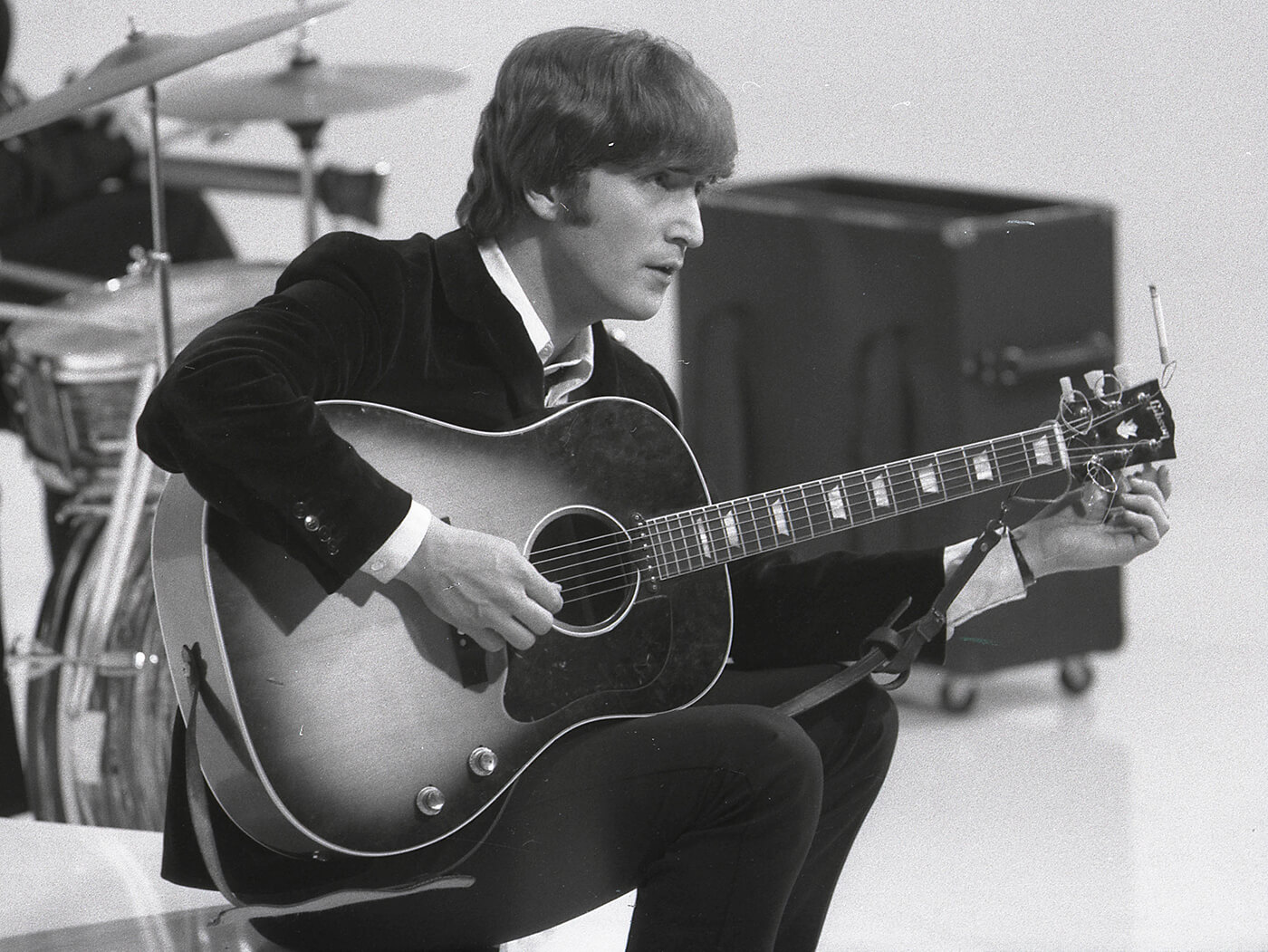

October ’64 at EMI Studios on London’s Abbey Road, and strange noises were heard coming from Studio 2. The Beatles were recording I Feel Fine, their next single, and a visitor from Beat Instrumental magazine reported that the song began with what he called “a very odd sound”. He asked for an explanation from Paul McCartney, who said the sound appeared at first as a mistake when he played a low A at the start of the song and heard some feedback from John Lennon’s unattended J-160E and amp.

Producer George Martin later credited the idea to John, who he said had been messing around with feedback from his J-160E. However the sound came about, it was certainly an early intentional use of feedback in the studio – if not quite of the intensity and type that we associate with slightly later records by The Who, Hendrix, and others. “The Beatles love oddness and decided to leave it in,” the Beat man concluded, summing up perfectly the group’s admirable approach to exploration.

Yours to cut out and keep

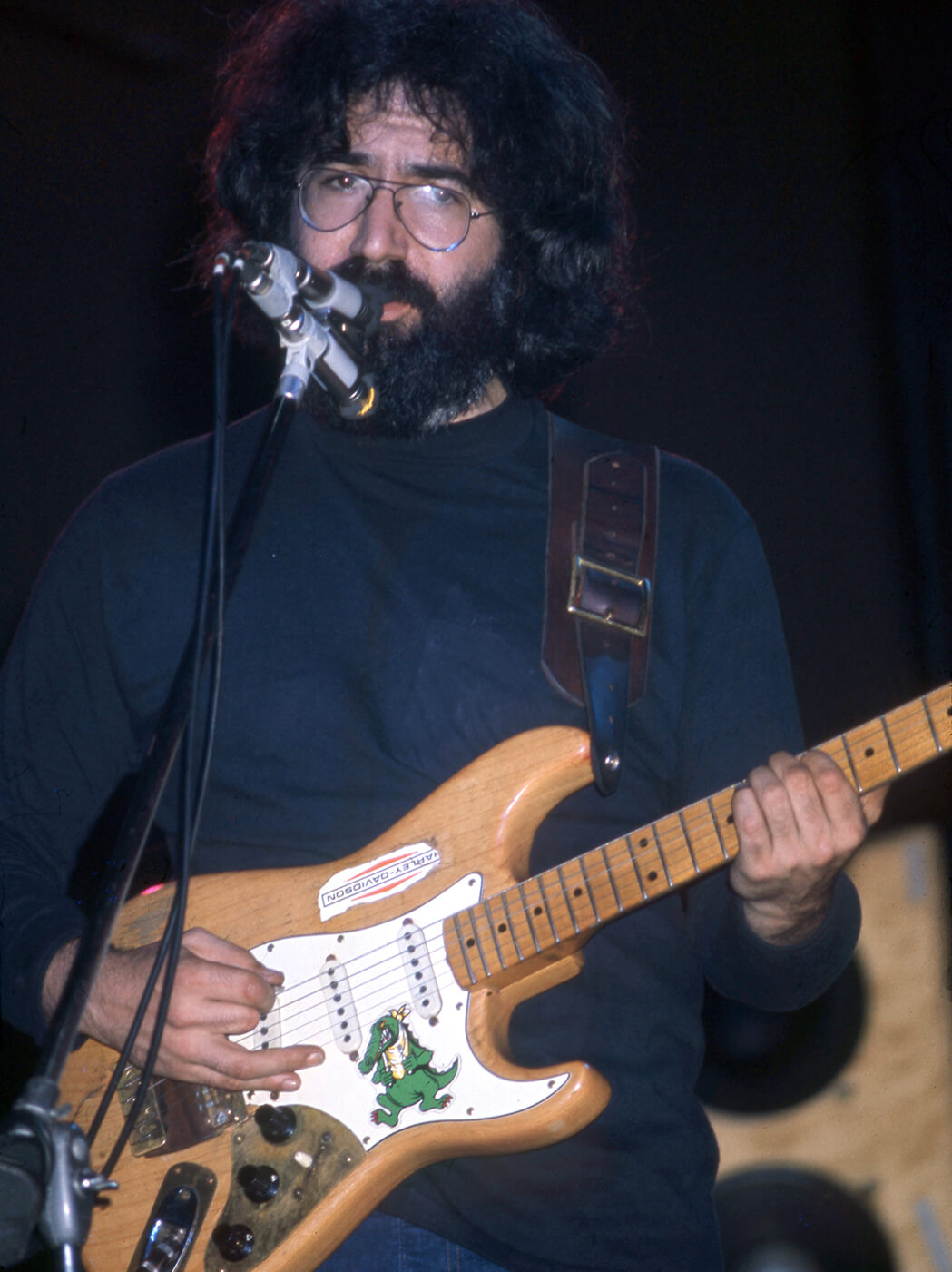

Jerry Garcia’s ‘Alligator’ Strat recently came up for auction, a guitar he used a lot in the early 70s. The Dead man had accepted it as a gift from Graham Nash, and apart from serious mods to bridge, controls, and more, it got its name from a large sticker featuring a green alligator on the pickguard, along with a couple more on the body for Harley-Davidson and a presumably ironic ‘Policeman Helper’. Of course, Jerry was hardly the first to adorn his axe with stickers.

Woody Guthrie might not have been the first, either, but he was one of the earliest to make a mark with a profoundly political sticker. With his dust-bowl ballads, Woody was the voice of the blue-collar worker in the American Depression of the 30s, famously singing This Land Is Your Land. He adorned several of his guitars – mostly Gibson acoustics, including a J-45, an L-00, and an SJ – with a sticker that declared ‘This Machine Kills Fascists’. And he wasn’t joking.

Works for that? Might work for this

Eddie Phillips of The Mark Four was looking for a way to keep a drone going on his low E-string while he hammered-on a solo with his left hand on the other strings. He tried sawing the string with a hacksaw, which seemed pretty good – until he realised he’d gouged some big grooves in the bottom horn of his beloved ES-335. Then he had a brainwave. He went to his local music store, bought a violin bow, and tried that. After his drummer suggested that rosin on the bow might help things along, it worked. A bonus was that if he flipped the bow over, he could use it as a sort of bottleneck.

“I loved to do things like that on guitar that weren’t normally done,” Eddie said later. “People were still happy to play guitars in the normal way, which is OK, but I was always trying to do something a little bit different. It all added to our reputation as being this slightly off-the-wall band.” The Mark Four morphed into The Creation, and while that band never quite earned the fame they deserved, it seems that Jimmy Page certainly noticed Eddie’s continuing application of the violin bow to the electric guitar.

Don’t be afraid to rip it up

Dave Davies was all fired up after some romantic twists in his young life when he was left alone with a razor blade and his little green Elpico amplifier. The amp didn’t stand a chance. Dave slashed at its speaker cone. Now, the sound matched his mood: distorted and angry.

When he and his band The Kinks recorded You Really Got Me at IBC studios in London in July 1964, Dave’s abused amp provided the perfect sound for the song. The intro says it all, and it’s become a classic.

Dave recalled later that he would connect the “modified” Elpico to an AC30 for added volume, and maybe that’s how he used it for You Really Got Me. Later, this sort of thing became easier when pre-gain controlled the preamp and post-gain or master volume controlled the power amp, but Dave’s idea was similar. Anyway, his rasping guitar prompted the Disc Weekly reviewer to single out the “gimmicky tribal noise” of You Really Got Me for praise. A tribe of razor-wielding Daves – now there’s a scary thought.

How many strings do you use?

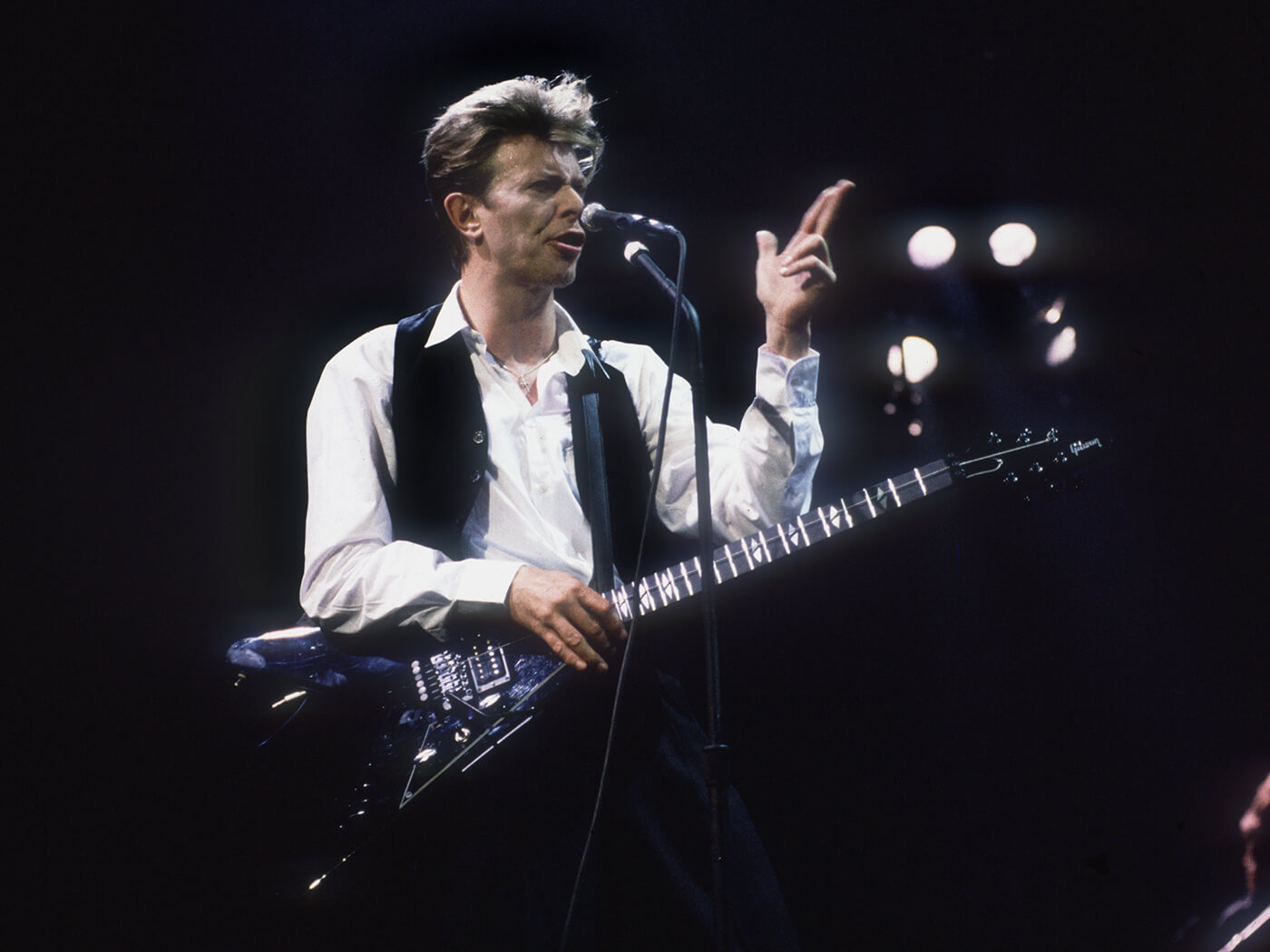

Presumably fed up with tuning his acoustic 12-string, David Bowie took to the stage during one part of his Sound+Vision tour in 1990 with a rather fine looking black Flying V90 Double, complete with Floyd Rose and fancy split-diamond fingerboard inlays. The thing was, on closer inspection, the guitar had just one string. Reportedly the D-string.

Maybe it harked back to Dave’s early days, when he learned to play by tackling a one-string ukulele (or so he claimed, surely with tongue in cheek). Maybe it was a reaction to the kind of thing that Adrian Belew, his sparring guitar-partner on that tour, would play. Maybe it just suited the kind of relatively simple riffs he needed for the Spiders-era section of these retrospective shows. And maybe it’s worth a revival. We all know what happened when Keith Richards went in the other direction and dispensed with just one of the six strings he felt he didn’t need any more…

Many of the examples we’ve looked at happened in the earlier days of music, and there’s a reason for that. Today, modern tech is certainly convenient, and most of us would be sorry if we didn’t have it at our disposal. There are so few limitations today on what we can achieve – but that can come at a cost to adaptability and rule-bending.

Perhaps there’s something fundamental missing from this brave new world. It would be nice to think that we still have the choice to creatively abuse and misuse if we want to. Why not give it a try some time?

For more essential guides, click here.