Chord Clinic Part 1: The basics

No matter what your level of ability, there’s always room to improve. First, let’s go right back to basics…

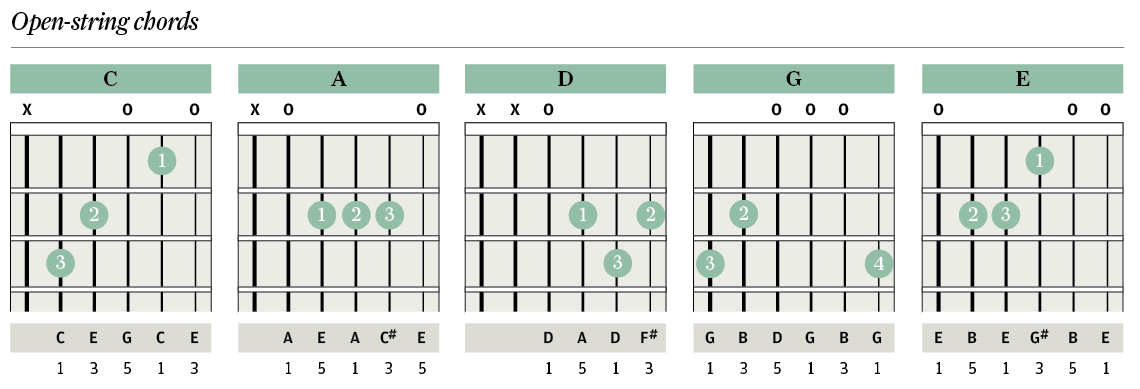

Open-string chords

Above are the five basic major chord shapes. We call these open-string chords because they are down at the low end of the guitar, and make use of open strings whenever possible. In music, terms such as up and down, or high and low, refer to pitch. So the low end of the guitar is where the low notes happen, near the nut. The high end of the guitar is the dusty bit up near the pickups or soundhole. The high E, or first, string is the thinnest one that makes the highest sound, and the low E, or sixth, string is the thickest one that makes the lowest sound. When describing tunings, the convention is to go the other way, from the lowest-sounding string to the highest. That makes the open strings on the guitar E A D G B E, low to high.

Let’s take a detailed look at the first diagram, C major. The six vertical lines are the guitar strings going from thickest to thinnest. The horizontal lines are the nut at the top, then the frets crossing the strings working their way down. Above the diagram, we get the name of the chord as it would appear in sheet music or a chord chart. The capital letter C means “C major” – mostly, we don’t bother to say the word “major”. Then we have an X above the nut on the thickest string, which tells you not to play the low E string. The two zeros tell you to let the G and high E strings ring open.

The circular blob with number one in the middle represents your first finger stopping the B string on the first fret. The number two is your second finger on the second fret, D string, and your third finger is over on the third fret on the A string. Use the tip of your third finger to mute the low E string and you’ll be able to strum away without hearing the open E droning away beneath your lovely C major chord. Chords sound most powerful and focused when the root note (that’s the name-note) is in the bass.

At the bottom of the chord diagram, the row of letters are the names of the notes you are playing, so C major consists of C E G C E. In fact you need only the notes C, E and G to make C major, and this means there are dozens of possible shapes for C major on the guitar. The way that the notes of a chord are arranged is called a voicing. This voicing mixes doubled notes with the bright tone of open strings, resulting in a jangly sound.

Finally, at the bottom we have a row of numbers, and this is where we get a bit theoretical. These numbers show the relationship of the notes in the chord to the major scale built on its root. So C, E and G are notes one, three and five of the C major scale and would be called root, third and fifth. Sometimes, you will see the letter R for root instead of the number one. Any chord consisting only of the root, third and fifth is called a triad.

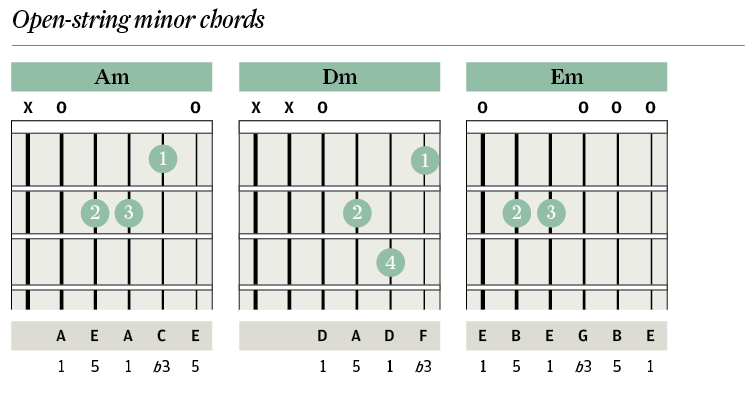

Open-string minor chords

There are just three open-string minor chords. These are also built from the root, third and fifth, but in a minor chord the third is flattened – or lowered – one semitone, which is the same as one fret. So we have a ♭3 or “flat third”. Compare E, A and D minor to the major chords of the same name, and in each case you’ll find one note that has been lowered by one fret. We could also say that a major chord has a major third – which is four semitones, and a minor chord has a minor third, which is three semitones. In fact, major and minor chords are named after what kind of third they have. The fifth doesn’t change. In chord charts, we use a small m next to a capital letter for a minor chord, but when talking about minor chords we always use the full name – A minor, E minor, etc.

Work your way through the chords in figures 1 and 2 in turn, and try playing the notes one at a time – as an arpeggio – from low to high. All the required notes should be sounding cleanly with no buzzes or rattles. Are the open strings sounding, too? Even quite experienced players are surprised to discover that sometimes they don’t fret common chords cleanly. Can you name the notes of the chord as you play them? When you come to play the A, Am, D and Dm chords let your fret-hand thumb creep over the top of the neck to mute the low E. D is just a four-note chord – it’s not the end of the world if you hit the open A string when strumming D or D minor, but ideally the open D should be your bass note.

Take a closer look at the G chord; you might be surprised to find it fingered here using fingers two, three and four. The idea is to make it easier to get from G to C, as it places fingers two and three very close to their destination when moving to C. These two chords are closely related and with this fingering you’ll be able to switch between them very quickly. If you can already, it’s OK to wear a smug expression for a moment.

Armed with these eight chords and a capo, it is possible to play a very large number of songs – possibly the majority of songs ever written. Commit the shapes to memory (remember their names, too – the major chords spell the word “CAGED”). If you’ve never tried bashing (I mean strumming) your way through a chord chart and you need help getting started, have a look at Brown Eyed Girl by Van Morrison, For the First Time by The Script or Good Riddance (Time Of Your Life) by Green Day, or search the web for the song of your own choice. Strum the right-hand patterns that you hear in the original and practise the chord changes back and forth until you can keep up.

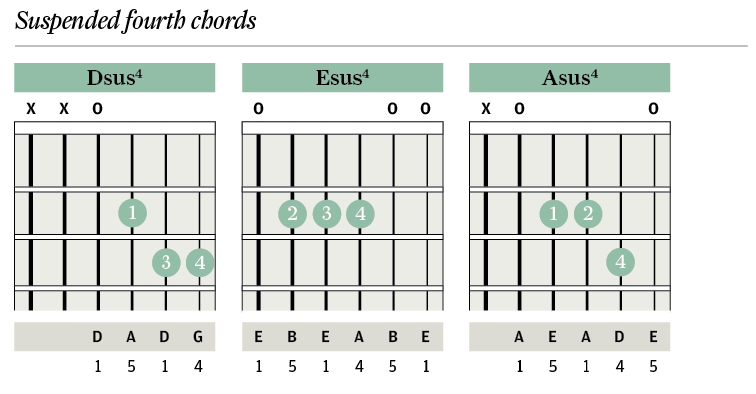

Suspended fourth chords

If you grab the third of a major chord and make it go one semitone higher, it will become a fourth. Chords consisting of a root, fourth and fifth are known as sus4, short for “suspended fourth”. The interesting thing to note about suspended fourth chords is that they seem to want to progress back to the normal major chord. A lot of songwriters seem to have discovered the Dsus4 to D chord sequence at some point, and it’s used a lot in popular music of many genres. So, with the chord boxes on the right, we make it possible to do progressions from Esus4 to E and Asus4 to A. Give it a try.

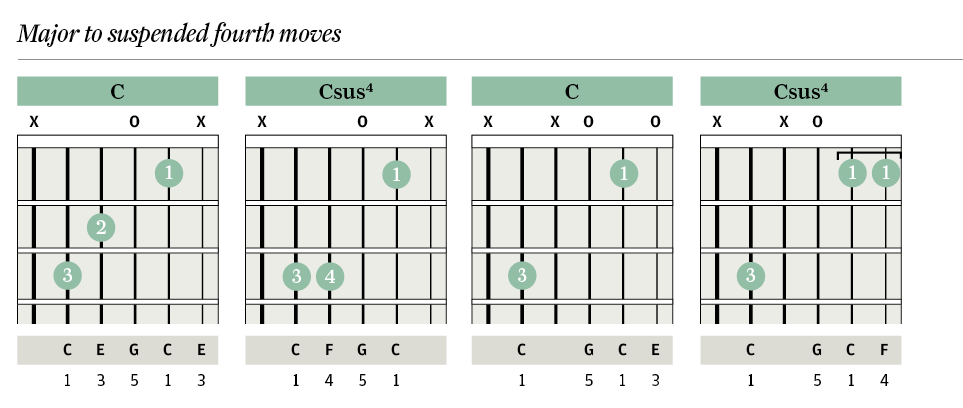

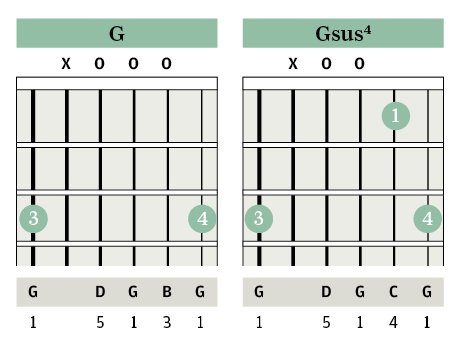

Major to sus4 moves

In chord shapes where the third is doubled, such as C and G, we need to have a rethink – for now, we want to avoid having the third and fourth in the same chord. In the first two shapes, the high E string is muted with the underside of the index finger and the pinky can be used to produce the Csus4 chord. The next two shapes mute the D string and then add the sus4 on the top string. The final two shapes modify the G chord by muting the A string with the underside of the third finger – making it possible to produce a sus4 chord by dropping the first finger on the B string.

Sus4 chords have a restless and unresolved quality, which can add interest to chord sequences. Try making up some of your own using just sus4 chords, or alternatively try following a sus4 chord with its major chord. Mix in the occasional minor chord and see what you come up with. Next time, we’ll continue to add notes to our open-string chord shapes and on the way sort out the difference between a sus2 and an added nine. Enjoy!