Chord Clinic Part 2: Sus chords

Suspended chords can create an ethereal, hypnotic feel, and are a valuable addition to your chord vocabulary. In the second instalment of this series, we delve into the world of the ‘sus’ shapes…

Sus2 and add9 chords

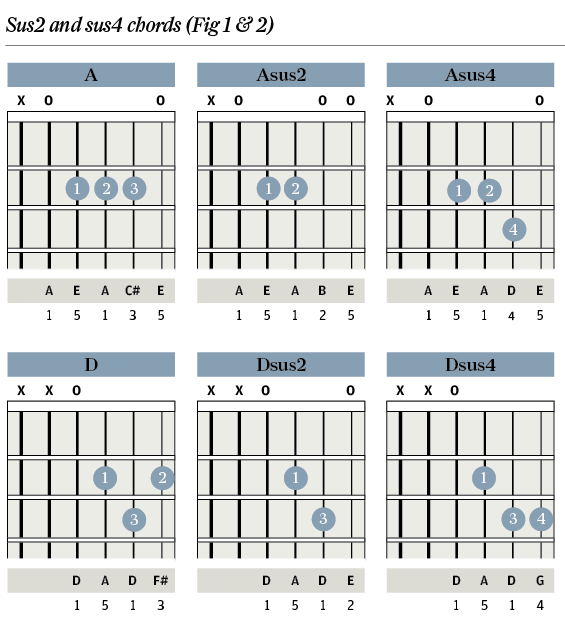

Last month, we got started with the basic major and minor chord shapes and then took a look at what happens when you raise the third of a major chord one fret – producing a sus4 chord. Sus is short for suspended, and the only other note you can suspend is the second. To make a sus2 chord, the third of a major chord is lowered a whole tone, which is the same as two frets. This produces a chord with the formula root, second and fifth.

Asus2 and Dsus2 are easy chords to play, as you release a finger and the sus2 note is found on the open string. Try alternating between the major chord we studied last month and the sus2 chord for a pleasing mixture of chord movement, together with the effect of not really going anywhere. Then try playing D, Dsus2, Dsus4, Dsus2 round and round and you’ll get something like the intro to KT Tunstall’s Other Side Of The World. The sequence works just as well with A chords, and if you end on the major chord instead of the sus2 you might come over all Christmassy as John Lennon sings “And so this is Christmas…”. Sus chords don’t seem to want to progress in the sense of moving on to a different chord – they’re really happy just to let the suspended note return to its original pitch in the major chord.

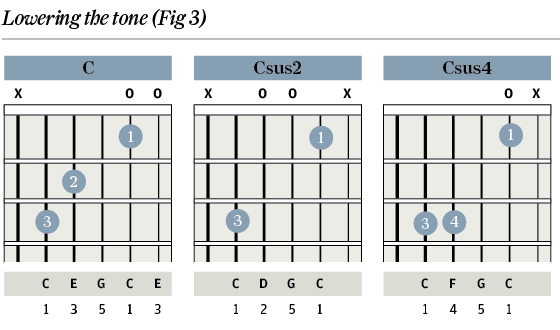

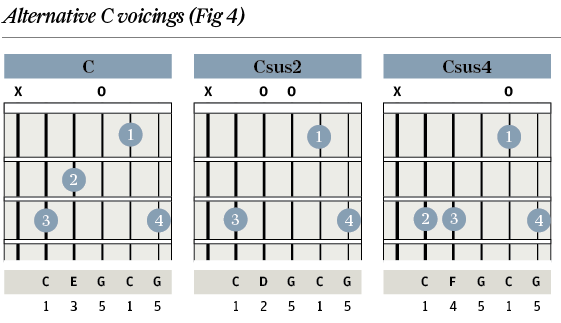

The other three major chord shapes can’t be turned into sus2 chords quite so easily – but it’s definitely worth trying. For the Csus2 shape, we have a couple of options, the first of which involves muting the open E string with the underside of the first finger and letting go of finger two. There is a sus4 voicing available, too, as we saw last time. These low suspended chord voicings have a lot of character – try playing KT’s chord sequence using these C chords and see what you think.

If muting the open E is tricky for you, try dropping the pinky on the third fret of the top string and alternate between Csus2 and C major. Adding this high G note means we have a doubled fifth in the C chord – it has a chiming, ringing quality preferable in many ways to the doubled third in the standard C chord, or the shapes in figure 3, which don’t use the top string at all. A quick re-fingering also lets you play a Csus4 voicing that goes well with the other two shapes.

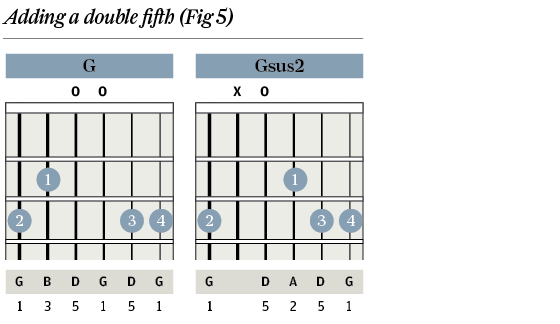

Figure 5 does for a G major chord what figure 4 did for a C major, taking away the doubled third and adding a nice chiming doubled fifth instead. Gsus2 also sounds great with this voicing – if you are alternating between the sus2 and the major, there’s probably no need to keep putting your first finger back on the A string. Just mute the A string all the time with the underside of your second finger.

Subtle variations in chord voicings, like those in figures 3, 4 and 5, can add a great deal to your music. Even if you are just playing a cover version of a well-known song, adding a chord with some extra colour, an unusual voicing or a suspension can really take your version to the next level. Be prepared to experiment, and always trust your ear for what sounds right.

Add9 and add11 chords

In all the shapes we’ve looked at so far, we’ve gone to a lot of trouble to avoid having the third in the chord along with the sus2 or sus4. So what happens if you simply add the second or fourth note to the chord, leaving the root, third and fifth in place? Answer: you get an add9 and an add11.

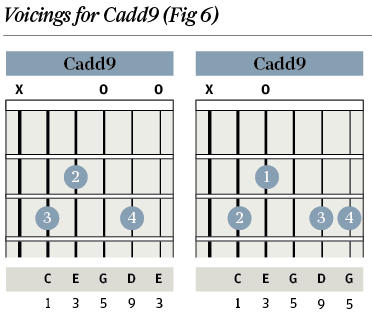

The convention is that these added notes are viewed as coming from above the fifth, which takes them up into the next octave, where a second becomes a ninth and the fourth becomes an eleventh (think of it like this: if C is one, D is two. Now keep going: EFGABCD, etc, and you’ll find D is the ninth note above C and F is the eleventh). Heading back to C major, we have a couple of voicings for Cadd9.

Take your pick between the one with the doubled third or the doubled fifth. Which one you choose could depend on the next, or maybe the previous chord. For example, if you have just played G major, as in figure 5, it might be musically effective to choose the second shape, which will keep the top two notes the same. It might be tempting to follow that with the Dsus4 chord from figure 2 so that three chords in a row have the same two top notes. Stick a capo on the second fret and you’re almost heading into Oasis’ Wonderwall territory, but I was able to track down songs by artists as diverse as Alicia Keys and Tom Petty that use these kinds of chord sequences.

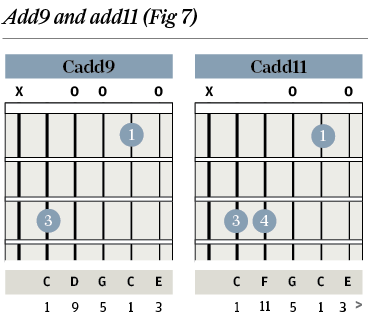

Figure 7 introduces another Cadd9 chord, this time with the added ninth low down on the D string. This pairs very nicely with an added 11th chord with a similarly low position for the added note. Played on its own, this Cadd11 produces quite a clash with the open E string. However, played in sequence with the major chord and the add9, the forward movement seems to conceal the clash. It’s worth remembering that forward motion in a chord progression can make many kinds of temporary dissonance tolerable.

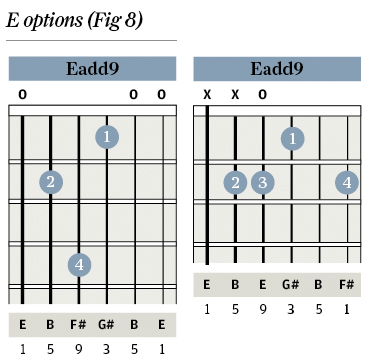

Somehow, we’ve managed to get this far without having any E chords. In fact, Eadd9 in the lower voicing can be a bit of a stretch. Try mixing it with the open E chord and Esus4. The higher voicing (the second chord diagram in figure 8) has a sweet quality, which makes me think of Barry Manilow not being able to smile without you, although Jimi Hendrix turned this into a movable shape and played the sliding chord intro to Castles Made Of Sand. But I’m saving movable shapes for a future instalment.

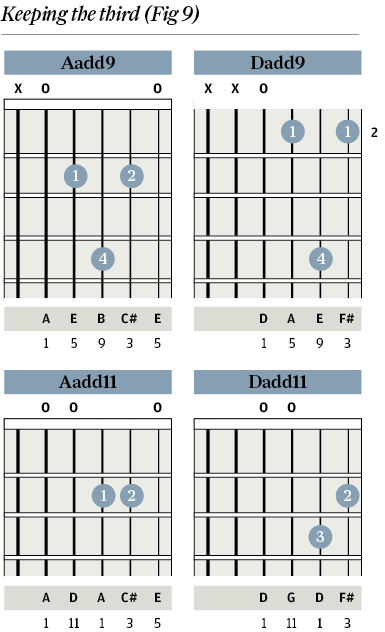

We’re going to finish off with Aadd9 and Dadd9, both of which need to be compared with the sus2 chords from figures 1 and 2. Keeping the third in the chord sounds so much sweeter than the comparatively stark sus2 voicing. Different is not necessarily better – we’re looking at chords in this way so that you can choose voicings which suit the music you are playing or writing. Just to end with a bang, the last two chords in figure 9 are the wonderfully ambiguous Aadd11 and Dadd11, where the low position of the 11th makes you wonder if these are A and D chords at all. Oh, and we left the fifth out of the Dadd11 chord because the fifth is always the first note to leave out when things get tight. Chords are wonderful things…