The Genius of… Damaged by Black Flag

Angry, messy and fraught with all sorts of complications, this is how Greg Ginn and his Ampeg Dan Armstrong made one of the defining records of the hardcore scene.

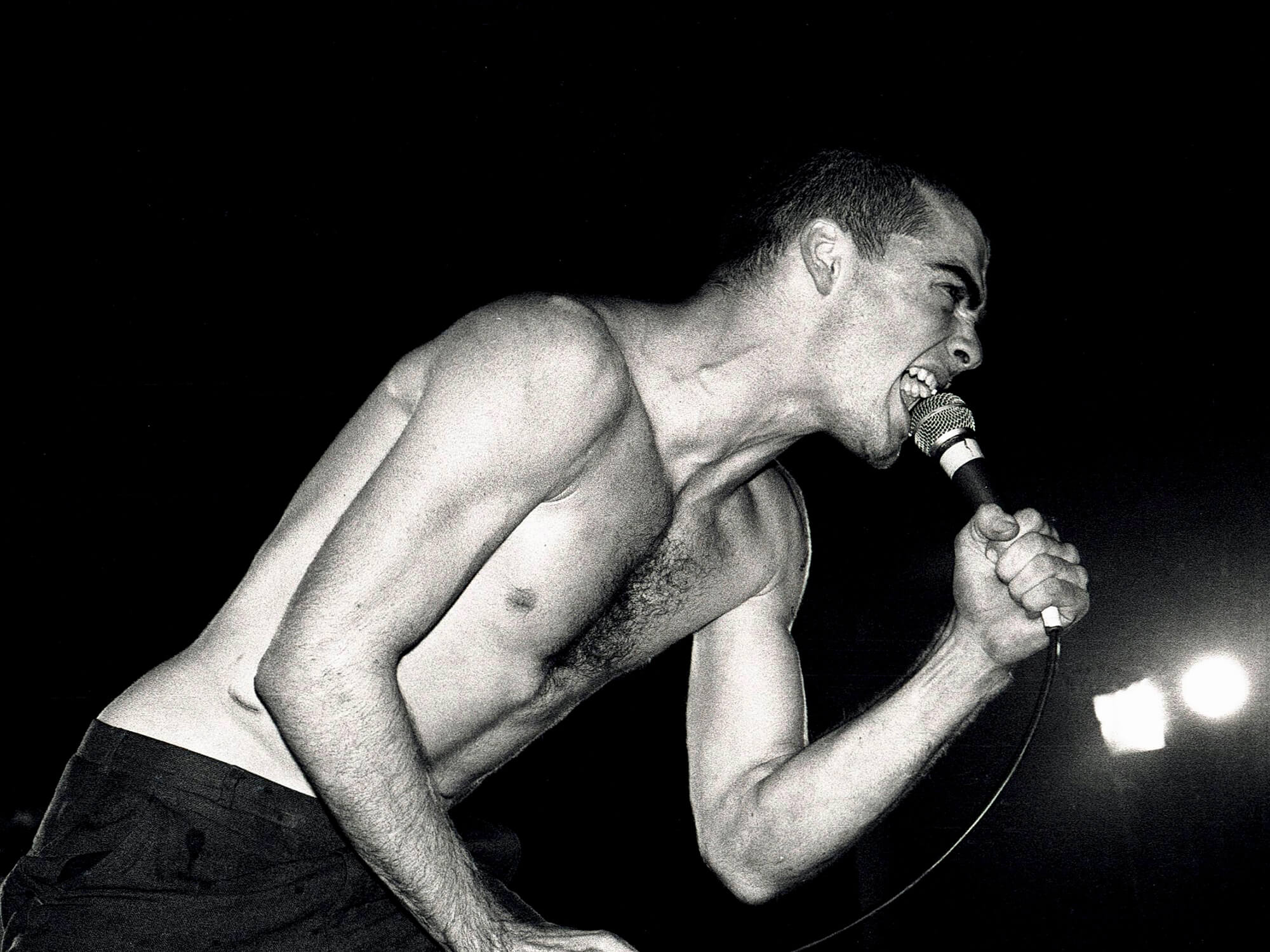

Henry Rollins of Black Flag. Image: Steve Rapport / Getty Images

Most people don’t know what hardcore is. They probably know a little about punk – safety pins, Pistols, Clash, Ramones… but all that died out years ago, right? Well, here’s a question: how many of the same people who believe punk croaked in 1979 might also recognise Black Flag’s ‘bars’ logo? Some, at least, and that’s because they remain a rare sort of band: uncompromising and not at all famous in the wider world, but also iconic in the genuine sense of that word.

Hardcore has been an outsider’s paradise for 40 years, and to this day it’s hard to overstate the role Black Flag played in riding roughshod over artiness with aggression, finding an anti-conformist, grotty corner of an already out of the way sub-genre while the surfers topped up their tans outside in Hermosa Beach, a clean and tidy city a few miles outside Los Angeles.

Four decades along the line from its release on SST Records, the label owned and operated by Black Flag guitarist and creative overseer Greg Ginn, the band’s debut album holds sway as a pivotal punk text. Damaged’s jagged blend of grimy riffage, tinny, pummelling drums and Henry Rollins’ anguished yell is being replicated right now, this very minute, in scenes around the world. It could be released by a tiny cassette label in 2022 and sound absolutely vital in the way faultless records you know no-one will ever hear sound vital.

Organised chaos

Greg Ginn was an odd kid, then an odd teenager. He displayed the twin seams of DIY spirit and musical ambition that would come to define Black Flag – repairing radios for resale while inhaling records by the Grateful Dead, BB King and Television, having read about the nascent New York punk scene in the Village Voice. Before long he’d formed a band alongside bassist Chuck Dukowski and vocalist Keith Morris. Panic played parties – in and out fast, say all you need to say in 20 minutes or less before the cops shut you down. They’d eventually change their name to Black Flag at the suggestion of Ginn’s younger brother, the artist Raymond Pettibon, whose work would give the band its indelible logo and look.

Black Flag cycled through singers – with Ron Reyes and Dez Cadena following Morris, who left to form another pioneering hardcore band, Circle Jerks – like they cycled through confrontations with the cops, who had the band’s number. The meathead element in their following, jock types hopped up on suburban ennui, took their grinding, unreconstructed music and invitations to mayhem at face value. The band slamdanced their way towards audiences in the thousands and began to look outside Los Angeles for shows as the heat was turned up by the police, who reacted to a Black Flag flyer with straight-ahead violence, and club owners banned hardcore bands.

If Black Flag had folded at this point, they would have left behind a fistful of essential hardcore documents, from the Nervous Breakdown EP (with Morris on vocals) to Jealous Again (with Reyes) and Six Pack (with Cadena). But when Cadena’s voice buckled under the weight of constant touring they found their next step in Washington DC, where a kid named Henry Garfield was waiting.

Rollins joins the band

By the time he joined Black Flag, Rollins – a childhood friend of Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye – had already seen the blooming of a seminal hardcore scene in his hometown. He fronted a band called State of Alert, releasing an eight-songs-in-eight-minutes 7-inch through MacKaye’s Dischord label in March 1981, sang on stage with Bad Brains and met Black Flag when they stayed at MacKaye’s house during a tour. He kept in touch and took a call during a shift at his ice cream store job, with the band asking if he’d come up to see them.

“I joined Black Flag by showing up at an audition in New York City in the summer of 1981,” he said in We Got the Neutron Bomb. “The first days were a jolt because they were living hard and low to the ground and I had no experience like that before. It was a bend in the road as they say. I had worked hard all my short life at multiple jobs. I thought I was quite the hard-working taskmaster type. Ginn was 10 times this.”

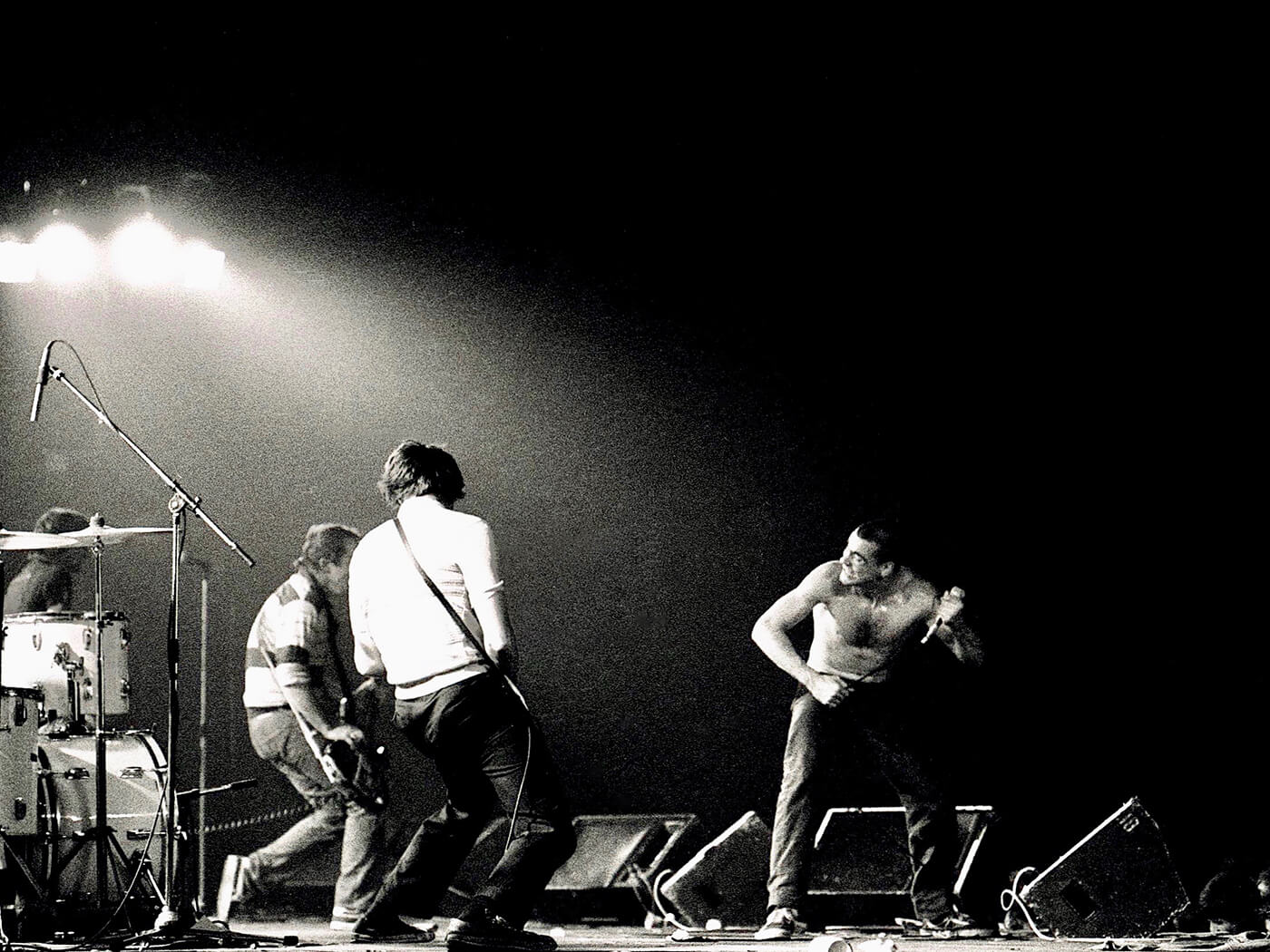

With Rollins – the opposite of the preppy Ginn in terms of look, with his broad shoulders, tattoos, close-cropped hair and stage wear of athletic shorts and little else – in place and Cadena on rhythm guitar Black Flag hit upon a line-up that allowed them to catalyse Ginn’s violent, pain-driven music live. Not everyone was convinced, though. “Henry reminded me of guys in my gym class that hated me because I liked Flag,” Heart Attack’s Danny Sage said in Steven Blush’s American Hardcore. “He was a joke and a poseur,” was Ted Kepley’s take.

But there’s a mountain of evidence on the other side of the ledger. Rollins gave Black Flag a physical, confrontational edge. He went toe-to-toe with audiences who wanted to beat him, burn him, destroy him. He took Ginn’s words and brought them to seething life. Damaged, recorded with SST’s house engineer Spot, mainlined pulverising anger, Rollins’ uncoiled bark and Ginn’s avant-garde-skirting riffs and seemed to capture hardcore in amber, while also suggesting that it was already time to reshape what might be expected from the genre.

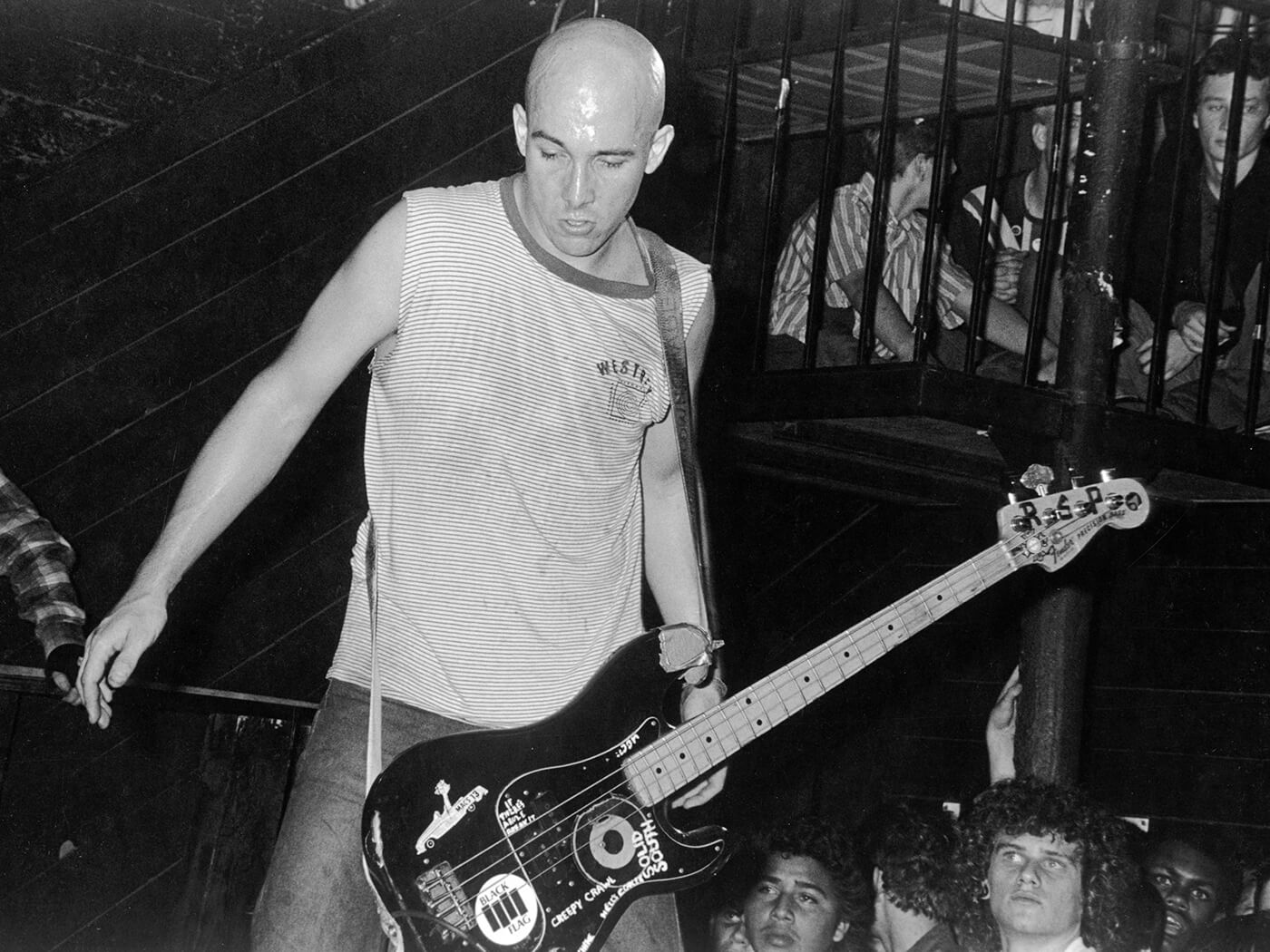

Ginn, who played an Ampeg Dan Armstrong Lucite throughout most of his time with Black Flag, using a cranked amp and natural distortion over a pedal, often appears to be clattering through both rhythm and lead parts at once, chopping in and out of Rise Above’s hardcore rallying cry before peeling off a short, sharp solo. Elsewhere he seeks to counterpunch against Rollins’ teeth-bared vocals, dredging up a grubby, horrible chug on Spray Paint and uncorking squalling noise on Dukowski’s No More, flinging leads around but always sticking the landing in its anchoring power chords. On the closing Damaged I his discordant playing accompanies Rollins’ apparently ad-libbed fall into a void of abuse and torment. It’s genuinely harrowing.

Practice is at seven

Things in Black Flag’s world rarely ran smooth, and the release of Damaged was no different. Ginn entered into a distribution deal with MCA, co-releasing the record with subsidiary Unicorn. But right before it was due to hit shelves MCA’s Al Bergamo decided that Black Flag’s music was “anti-parent”. Now, here’s where things get really messy. In Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad quotes SST’s Joe Carducci’s belief that this was a play to kill MCA’s tie up with Unicorn, who reportedly owed them a heap of cash. Black Flag put “anti-parent” stickers over the MCA logo on existing copies of Damaged before the whole thing ended up in lawsuits going back and forth.

In 1982, Black Flag released Everything Went Black, a compilation of their early recordings, under the band members’ names to get around an injunction, but the move landed them in front of a judge in the summer of 1983. Ginn and Dukowski spent five days in jail for contempt of court. “He wouldn’t even discuss it,” Rollins told Azerrad. “He just said ‘practice is at seven.’” Unicorn went bust later that year, with Black Flag’s members accusing them of all sorts of sketchy shit, and the band were free.

They’d also never be the same again. The revolving door kept spinning—Robo was gone soon after the release of Damaged, replaced in quick succession by Emil Johnson, Chuck Biscuits and Descendents’ Bill Stevenson. Cadena left, later playing with DC3, Redd Kross, Misfits, and alongside Morris, Dukowski and Stevenson in Flag. Dukowski followed him out of the door after clashing with Ginn, who recorded bass on 1984’s My War under the pseudonym Dale Nixon. All this chaos. All this bad feeling. Couldn’t be Black Flag all over, could it?

Infobox

Black Flag, Damaged (SST, 1981)

Credits

- Henry Rollins – vocals

- Greg Ginn – lead guitar

- Dez Cadena – rhythm guitar

- Chuck Dukowski – bass

- Robo – drums

- Spot – producer, engineer

Standout guitar moment

Rise Above

For more reviews, click here.