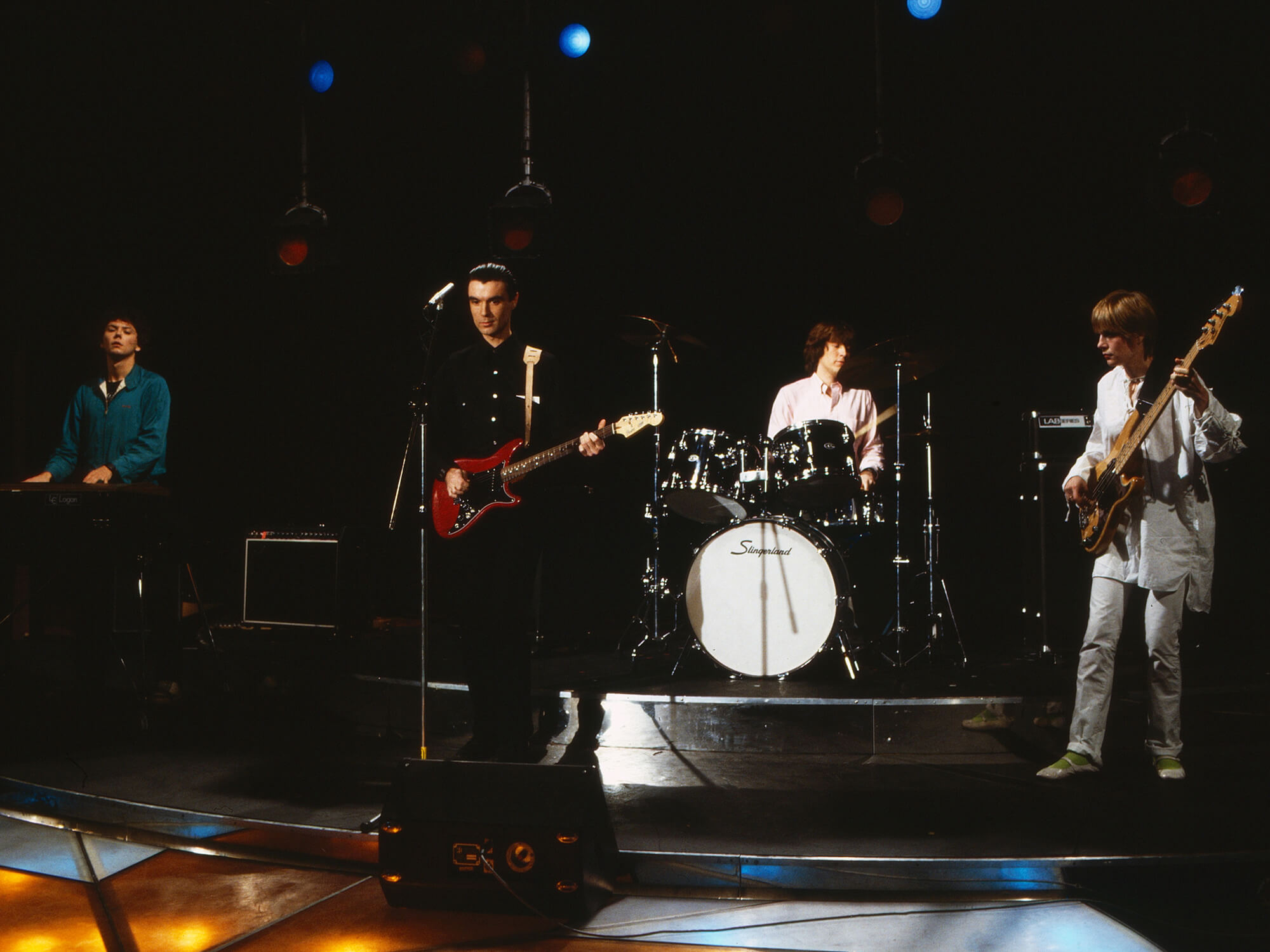

The Genius Of… Fear of Music by Talking Heads

Ripping apart and re-moulding genres with an artistic zeal, Fear of Music was Talking Heads’ absurdist masterstroke. Fascinating too, is the guitar’s often jarring and impulsive role within its delirious turmoil.

Image: United Archives / Getty Images

“Never listen to electric guitar” commands a typically unbalanced David Byrne on Fear of Music’s penultimate cut, aptly dubbed Electric Guitar. With any other band, you’d likely expect that a track titled after this most cherished of instruments would foreground it prominently – a flashy lead break here, pummelling chords there. But Talking Heads were not like other bands. And, Fear of Music is quite unlike any other album. In fact, the closest Electric Guitar comes to such a moment is probably a skittish, minuscule riff that darts away from the songs’ taut chorus in abject terror. Strident stadium rock, this was not.

This is Fear of Music, Talking Heads’ third album, and their second (of three) that they would make in collaboration with Brian Eno. Across its eleven tracks, the interplay of the band’s instruments with each other and Eno’s synthetic froth is explored, leading to some of the band’s most arresting songs, wherein the conventional mechanics of a post-punk band are upturned, dissected and re-organised. The wonderful results encompass a spectrum of often warring tones, textures and moods.

This ain’t no party

Talking Heads had formed only a few years prior, after David Byrne met drummer Chris Frantz and his girlfriend Tina Weymouth while studying at Rhode Island School of Design. Sharing a similar Dada-ist sensibility, Frantz and Byrne put together a musical duo, The Artistics – later to be re-named Talking Heads. After a period without a bass player, Weymouth (after three auditions) joined her partner and the idiosyncratic Byrne as the bassist. “We didn’t copy anyone’s style, and no one could copy ours.” Recalled Chris Frantz in his memoir, Remain In Love, “You could say that Tina and I were the team who made David Byrne famous. We were very good at shining the spotlight on him. We created a band that was post-punk before there was Post-Punk, new wave before there was New Wave, and alternative before there was Alternative.”

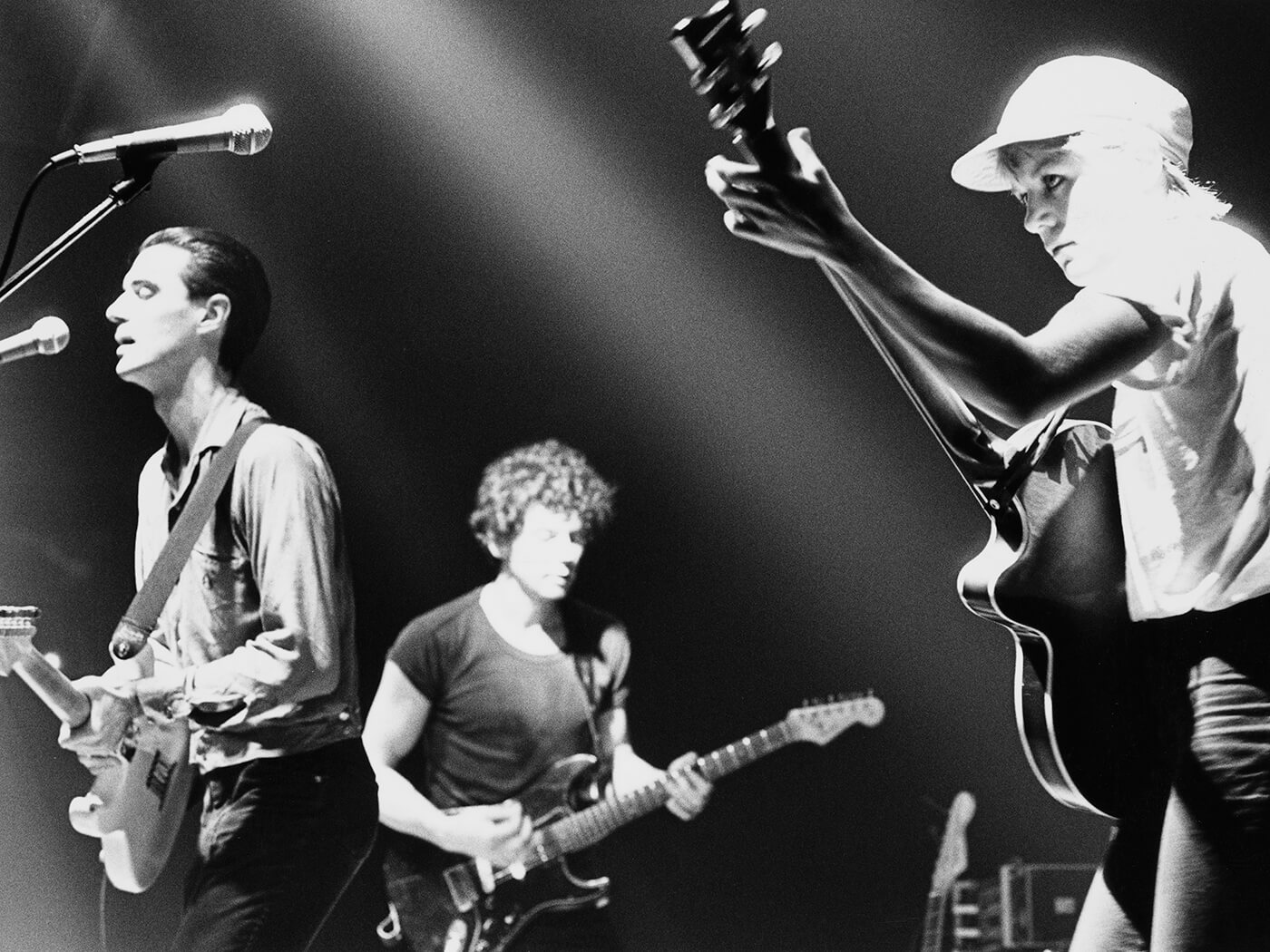

Relocating to New York, the trio began a recurring stint performing at the legendary CBGB club. They soon developed a reputation as a jaggedly-edged post-punk trio. The addition of The Modern Lovers’ Jerry Harrison on guitar and keys further solidified their sound. In 1977, debut album Talking Heads: 77 was released on Sire Records. Its janky key cut, and lead single Psycho Killer, served as something of a manifesto, emphasising Frantz and Weymouth’s rigid rhythmic nucleus, Byrne’s tense and neurotic vocal delivery and stiff rhythmic guitar work all round.

The following year, the band released the sophomore More Songs About Buildings and Food. This was their first in collaboration with Brian Eno. The former glam rock titan and synth pioneer of Roxy Music had started to cultivate a reputation as an indispensable musical foil for a range of artists including Ultravox, Robert Fripp and David Bowie. He’d kept an attentive eye on Talking Heads. “They took American light funk, people like Hamilton Bohannon, and married it with downtown New York punk or new wave. Now everybody does it but at the time it was a very new idea.” Eno recollected in The Guardian.

Working alongside the forward-thinking Eno invigorated Byrne, and the two became close creative and personal friends. “It was mutually beneficial and co-dependent in a way. We had musical things to gain from one another – each one could offer something slightly different to the other.” Byrne was quoted as saying in Red Bull’s Daily Note magazine.

“Eno is the only person who understands David’s guitar playing,” Tina told Creem in 1979. “David’s sense of rhythm is insane but fantastic. A song will start off a mess but become like a baby koala bear. It’s difficult to turn a really stupid idea into something brilliant. David turns a sketch into a painting. He’s great at convincing us that a crazy idea will end up brilliantly.”

This first collaboration bore much fruit, namely the delirious guitar textures sprinkled atop the warmth of Eno’s synth tones, evidenced on With Our Love, and of course, the moody cover of Al Green’s Take Me To The River, which broke the band into the Top 30 singles chart for the first time. It would later evolve into a fast-paced, live highlight (the best version of which can be seen on legendary concert film Stop Making Sense, with Byrne sporting his signature ‘big suit’).

Ghosts in a lot of houses

Though Fear of Music would be the second part of a trilogy of Eno-collaborations (culminating in the venerated polyrhythms of Remain in Light), this wasn’t at all the initial plan. Though sessions for the new record initially took cues from the Eno’s often chopped-up working methods, the man himself would only be called back into service after a creative roadblock was hit.

Putting aside some early ideas to pursue a more disco-oriented direction, Talking Heads decided to get back to basics, setting up live in Frantz and Weymouth’s loft – their former practice space. “We came into our loft, we set our instruments up. We then did something we’d never done before, we brainstormed, or we jammed.” Weymouth told The South Bank Show in 1979, when explaining the Fear of Music writing process. “Half the time it was awful, But then all these little interesting things would happen and that would get recorded on tape, and David would take it home. He’d pick out the parts that went along with his lyrical ideas.”

But, without the guiding hand of Eno, the group faltered. A quick phone call later, and the synth sage delightedly returned to co-produce the record. Before long, the sketchy, half-formed ideas began to find their footing, as Eno encouraged even more loose-form songwriting. Guitarists Jerry Harrison and David Byrne worked tightly together, making sure their respective melodic and riff figures combined, or – more interestingly – didn’t.

Byrne recalled in his superb book, How Music Works, that, from the outset of their working relationship, Eno had suggested the band play totally live in the studio, “Without all of the typical sonic isolation. His semi-blasphemous idea seemed worth a try, despite the risk of it resulting in a muddy recording. Removing all that isolating stuff was like being able to breathe again. The result sounded – surprise! – more like us.” Further impediments to band harmony were removed further as the new album got underway, and studio recording equipment was largely kept outside within a pair of mobile recording studio vans. These vans were unobtrusively parked outside and wires were carefully threaded through the building and windows so they could capture the sound from the loft.

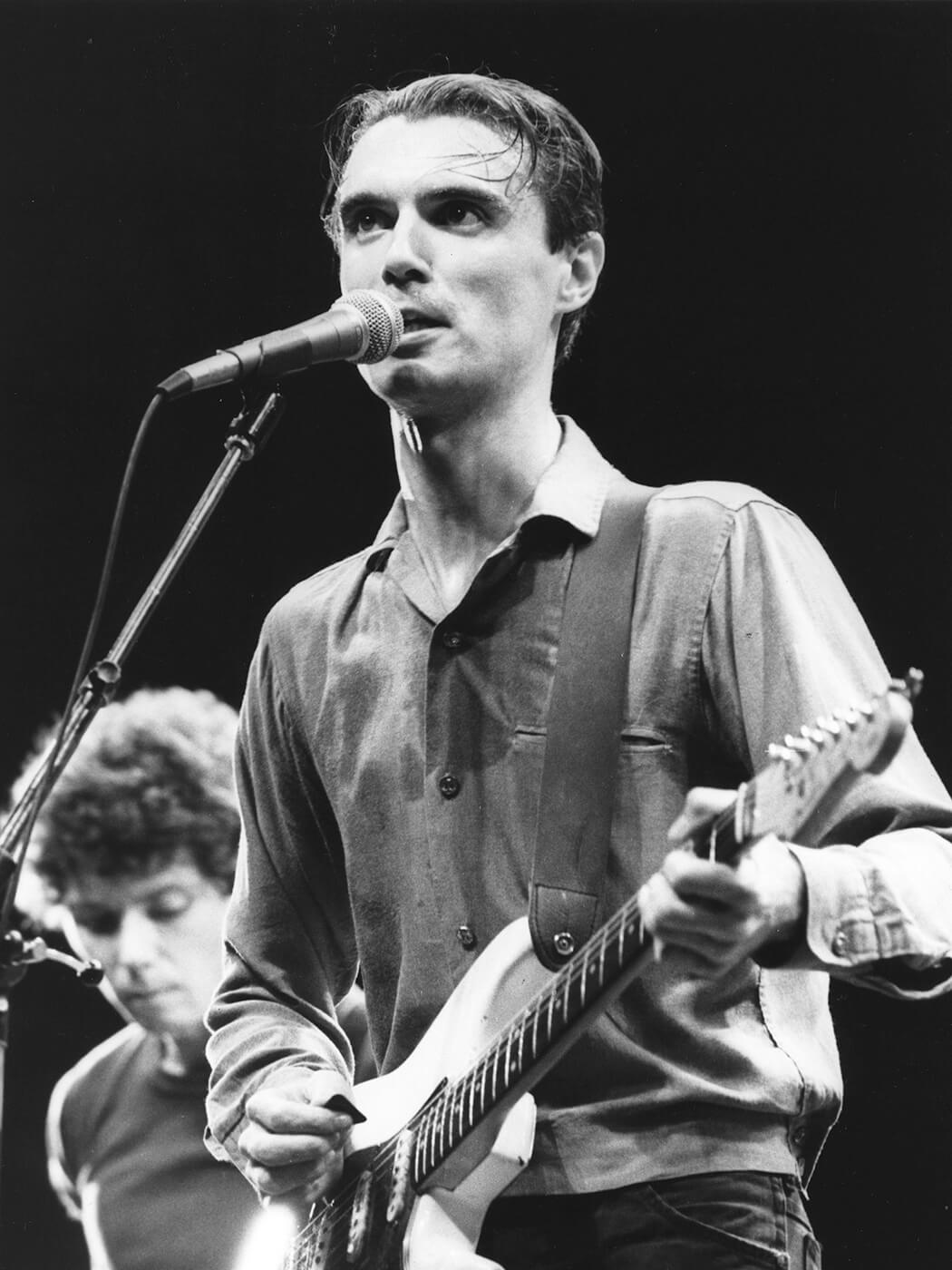

That ain’t allowed

Byrne was growing into a masterful rhythm guitar player by this point, as evidenced by the flurried chords underpinning the verse of Air, the tense muted chug of Animals and the almost Chic-like slick funk that circles the congas of I Zimbra. Meanwhile, Harrison was keen to accentuate the guitar landscape with laddering riffs and subtle arpeggiations. The eastern sounding riff which surges with an electricity between the lurching F and G chords that open Paper is a notable example of the pair’s approaches working harmoniously in tandem. Byrne’s funk guitar playing would only strengthen as the years passed, leading engineer Eric Thorngreen to eventually describe him as “One of the best rhythm guitar players who ever lived.” (Sound on Sound).

Though exact details around the precise gear that was used on the album is hard to verify, tone was most likely provided by a pair of Fender Twin Reverb amps, and Byrne was rarely seen without one of his two identical ‘63 sunburst Fender Stratocasters at the time. His tight Strat tone is unmistakable on tracks such as the bouncy Life During Wartime – the record’s first single, and perhaps the most ‘conventional’ sounding track on the record. At least from an instrumental point of view. Its bluesy double-stopping riff in A minor, tightrope-walks back and forth across Frantz and Weymouth’s robust groove. On the track, Byrne also paints one of the album’s most visceral lyrical landscapes – lyrically depicting a future wherein a revolutionary character keeps his head down within a violent dystopia.

“We recorded some basic tracks for songs I hadn’t written words to yet.” Byrne remembered in How Music Works “Later we altered and supplemented the sounds of the instruments well after they had been recorded.” Byrne goes on to say that often the final arrangement wasn’t locked down, and he’d be asked to supply lyrics and vocal melodies to tracks that would eventually develop further as production continued. …Wartime was one such cut. “Recording songs that were ‘incomplete’ was risky for me” Byrne says, “I wondered, could I really create a song out of pre-recorded riffs and chord changes? In some cases [like on Life During Wartime] I did it quite successfully.”

Up in the air

Another crucial track, the fragile Air, would become perhaps the band’s most misanthropic (though undeniably pretty) hymn. Beginning with ethereal female vocals, skittish rhythm chords and an eerie synth riff, the band swerve surprisingly away into a big chorus. As Harrison rings out a balmy C, F, C to A, Dm, A chord sequence, Byrne delivers a fearful, weary warning that “Air can hurt you too”.

For opening cut (and second single) I Zimbra, guitar virtuoso Robert Fripp entered the picture to supply an unusual computer-like pulse of lead guitar, which cascades into the song’s conga-dominated arrangement near its end. Eno had just finished working with Fripp on the off-the-wall No Pussyfooting and was enamoured by the guitarist’s keenness to process his guitar sound in a range of innovative ways. I Zimbra’s African influenced rhythms would also pave the way for the diverse polyrhythms and dance music-informing arrangements of their next long player.

Memories can wait

Upon release, on 3rd August 1979, Fear of Music was immediately recognised as being both a darkly hued, unsettling record as well as something quite special indeed by critics, and a notable evolution of the band’s musical universe. Despite critical adulation, this “brilliantly disorienting” (Rolling Stone) album failed to break significant commercial ground on either side of the Atlantic, though time has rightly shone more light on the album’s importance not just in the unfolding narrative of its creators, but to the broader progress of pop as the 1970s reached a downbeat climax.

Though the band’s third collaboration, Remain In Light is often held as the band’s singular greatest recorded achievement, it’s here amid the tense, paranoid musical landscapes of Fear of Music where the most balanced combination of the ‘Heads’ propulsive, wiry energy and Eno’s near-academic, investigative creative ethos is heard. As Simon Reynolds perfectly summed up in Rip it Up and Start Again, “Fear of Music represented the Eno/Talking Heads collaboration at its most mutually fruitful and equitable. His role encompassed being a kind of fifth player and an editor who spotted ‘little playing ideas that might have been accidents, or accidents of interaction’ that the band might otherwise have missed.”

On Fear of Music, you can hear a band adjusting themselves from being just four members of an oddball post-punk guitar band, into an expansive and multifarious musical vehicle. Diversifying their instrumental flavours, dabbling with complicated syncopation and taking their sharp instrumental textures in unconventional directions, Fear of Music� marked a perfect bridge between what the band were, and what they would become. It remains, even on its own terms, a bewitching listen.

Infobox

Talking Heads, Fear of Music, 1979, Sire

Credits

- David Byrne – Vocals, guitar

- Jerry Harrison – Guitar, keyboards

- Tina Weymouth – Bass, backing vocals

- Chris Frantz – Drums and percussion

- Brian Eno – Production and electronic treatment

- Robert Fripp – Additional guitar on I Zimbra

Standout Guitar Moment

Paper

For more reviews, click here.