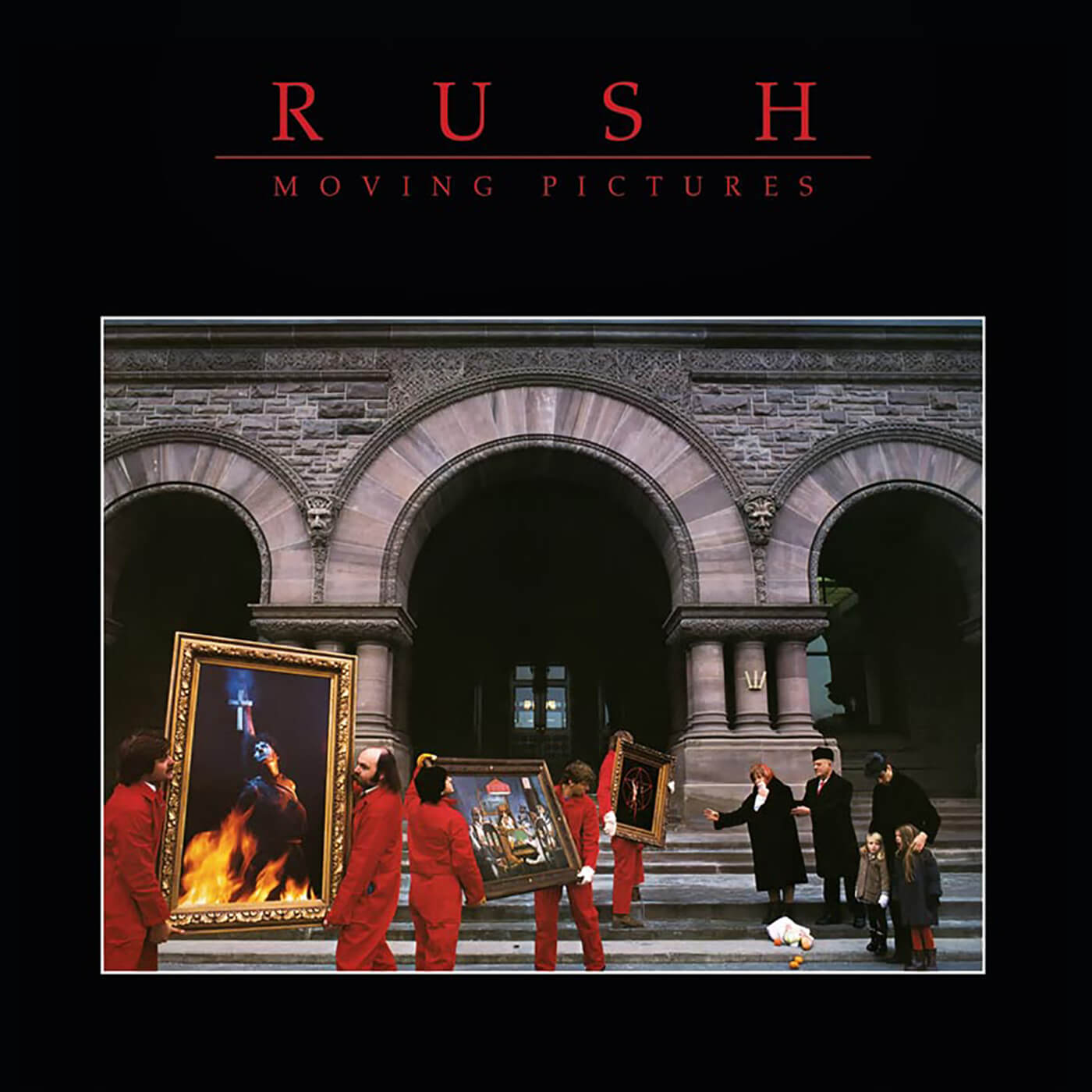

The Genius Of… Moving Pictures by Rush

With 1981’s Moving Pictures, the band streamlined their sound to conquer the mainstream without compromising their virtuoso talents.

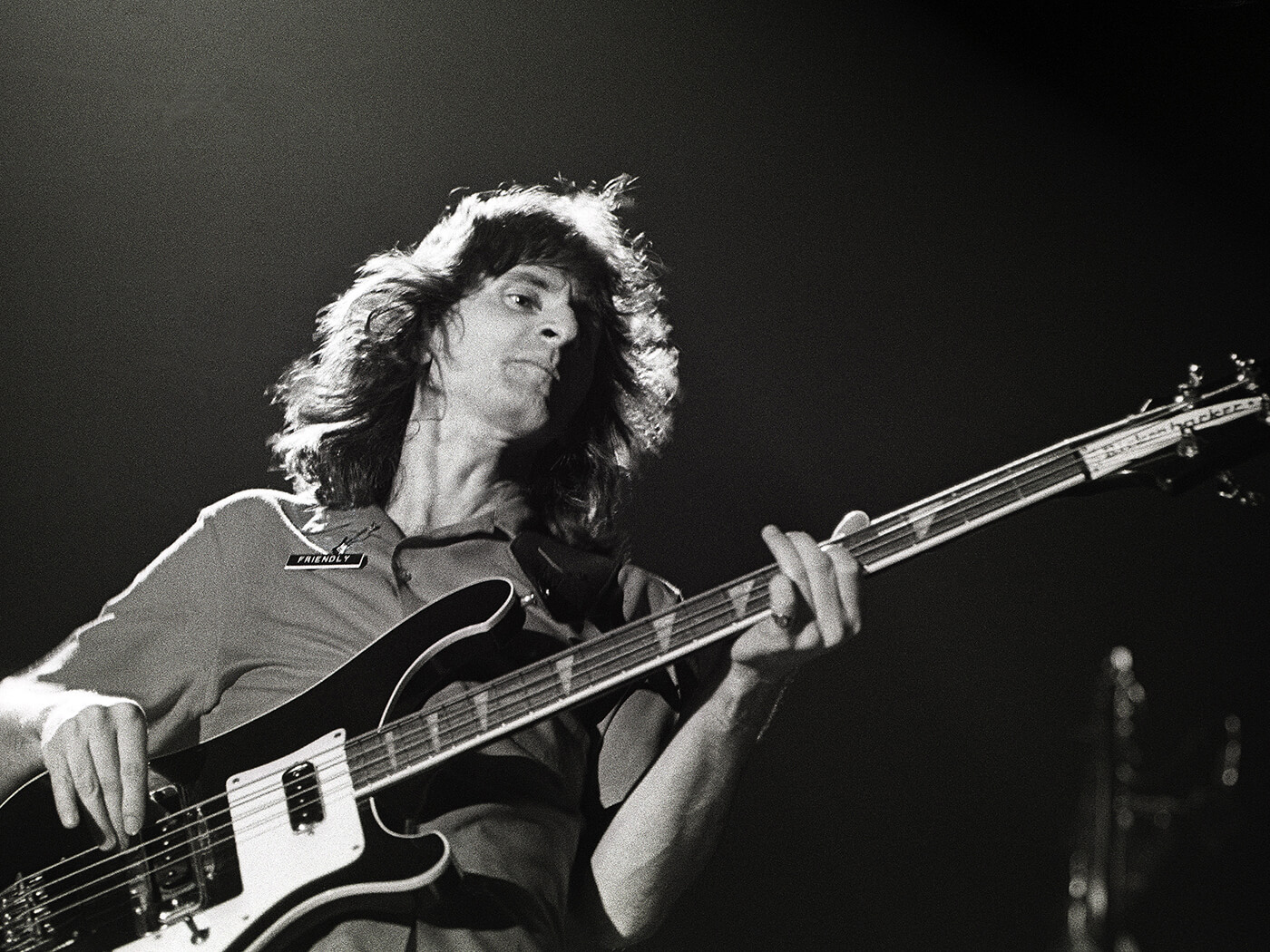

Rush. Image: Fin Costello / Redferns

The progress of prog

It was, to coin a phrase, “like punk never happened”. Odd it may seem now, but progressive rock entered the 1980s with commercial success at a high. Despite what you might read in the NME and Melody Maker of the time, punk’s safety pins had not burst prog’s bubble.

Phil Collins quite plausibly claimed that Genesis were too busy touring the world to take notice of punk. The Sex Pistols ‘I HATE Pink Floyd’ T-shirts didn’t stop Another Brick In The Wall (Part 2) being the band’s first Number 1 (and the first chart topper of the 1980s). Heck, even Supertramp – a sorta soft-prog band starring goddamn saxophone solos – were having huge hits in 1979.

But change was no doubt in the air. The new wavers who had followed the 1-2-3-4 redux of punk were also influenced by the arty rock of the early 70s – Bowie, Roxy Music – and, in turn, that wormed its way into the old 70s cocoons of prog. After all, Another Brick In The Wall was –whisper it to the kaftan wearers – almost disco.

The Buggles’ Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes shocked everyone by joining a then-splintered Yes in 1980, and helped steer them towards MTV with the likes of Owner Of A Lonely Heart. (The band had wanted to call the new outfit Cinema, but bowed to record company pressure… some appalled veteran fans dismissed them as ‘Yeggles’ anyway.)

Genesis edged towards ultra-sleek pop-rock, with 1980’s Duke being the trio’s last truly ‘progressive’ LP: from thereon, it was ‘Phil Collins and those other two guys’. King Crimson – which is basically whatever Robert Fripp says it is – reconvened with a new lineup, nicking Adrian Belew from Talking Heads/Zappa/Bowie bands to make angular, artful noisy noo wave. In proggy tricky time signatures, of course.

There were few prog bands who made the leap seamlessly, retaining old audiences while conquering new ones. Most notably, there was Rush. The Canadians had only just found chart fame, with 1980’s Permanent Waves birthing their first real hit in The Spirit Of Radio. In guitarist Alex Lifeson’s words, “We began writing in a tighter, more economical form.”

And if Permanent Waves saw Rush apply new edits, the following year’s Moving Pictures was more akin to having a whole new director.

Modern day warriors

There were probably many who doubted Rush had any real mainstream potential back then. This was a band who, on the verge of being dropped in 1976, went ahead anyway and cut the none-more-proggy concept album 2112. Satin kimonos an’ all. Luckily, it was a hit and notably, 2112 remains a favourite 70s indulgence of Foo Fighters Dave Grohl and Taylor Hawkins. So why change just a few years later?

Rush went into Moving Pictures with a blank slate. That was no surprise, as the trio had been incredibly prolific since their 1974 debut, releasing an album (often conceptual) every year and touring extensively. They were only heading back to record again – eventually at Le Studio, Morin-Heights, Quebec, their favoured studio from Permanent Waves (1980) through to Grace Under Pressure (1984) – because friends had convinced them they needed to capitalise quickly on the popularity of The Spirit Of Radio. The band spent a ‘studio vacation’ at (Bob Dylan sidekick) Ronnie Hawkins’ barn studio outside Toronto in summer 1980, and it yielded plenty of new ideas.

Although Lifeson says they had found a way of writing “shorter punchier songs”, it didn’t start like that at all. The first track they apparently completed for Moving Pictures was the 10-minute multi-themed The Camera Eye, something of a return to full-on 70s prog mode. Bassist/keyboardist/vocalist Geddy Lee later noted, however, that The Camera Eye was “the last really epic song we wrote.”

Changes aren’t permanent… but change is

Another new song was taking shape, and that was the gateway to Rush’s sleeker new 80s sound. But it was also atypical of Rush, as it involved outside help.

At Hawkins’ farm, Rush drummer and lyric writer Neil Peart was given a poem by Pye Dubois, who worked with Rush’s friends and fellow Canadian rock band Max Webster (Rush had guested on the latter’s Battle Scar from the Universal Juveniles LP of 1980).

Dubois’s poem was actually named Louis The Lawyer (not “Louis The Warrior” as suggested by Tom Sawyer’s final lyric) and Peart went about modifying the words. Peart, a massively talented percussionist, was never just a typical drummer… evinced by his role of Rush wordsmith and bookish intellectual. Peart later told the Rush Backstage Club newsletter,

“[Pye’s] original lyrics were kind of a portrait of a modern-day rebel, a free-spirited individualist striding through the world wide-eyed and purposeful. I added the themes of reconciling the boy and man in myself, and the difference between what people are and what others perceive them to be – namely me, I guess.”

The melody that Lee and Lifeson conjured for what was now called Tom Sawyer wasn’t a massive change in the Rush sound: but is was certainly more sprightly. Lee’s growing fascination with his Oberheim OB-X synth provided some intro growl and Lifeson’s chord patterns, although typical of his ringing, open-stringed voicings, stripped back any unnecessary “widdle”. Peart’s drums too, combine his usual poly-rhythmic power with some new strutting attitude. All told, this was a power-chording blast… apart from the expected time-shifting, prog-mungous guitar soloing section. Of that, Lifeson admitted, “I winged it. Honest! I came in, did five takes, then went off and had a cigarette.”

Tom Sawyer was, as they say, ‘a keeper’. “We don’t like to think about the album sequence until we’re done recording everything,” Lifeson later reflected, “but I think Tom Sawyer was always going to be the opener. Just the way it starts – it had to open the record.”

This was just the opening cut on a first side (in old LP terms) that saw Rush hit peak performance. Anti-authoritarianism, individualism and liberty were at the core of Moving Pictures. Rush had been here before of course, notably in the elaborate fables of 2112, but on Moving Pictures the Peart-penned morality tales felt more grounded in a real world, not some future sci-fi dystopia. Even when Peart did pen future fantasies, as on Track 2 Red Barchetta’s tale of a world where cars are banned, it turned out he was actually strangely prescient. Red Barchetta is another enduring fan favourite, its motoring (pun intended) energy providing a relentless distillation of Rush’s new-found power.

Shall we sing this instrumental?

Track 3 on Moving Pictures, was an instrumental. Sure, instrumental jams were reliable refuge for prog bands, and on 1978’s Hemispheres, Rush had cut La Villa Strangiato with its sub-title of An Exercise In Self-Indulgence… a bloating nine-minute instrumental in 12 distinct sections based on Lifeson’s nightmares. But YYZ on Moving Pictures was another level.

It was predominantly the work of Lee and Peart and once again baffling in its virtuosic heft, and even its title/structure alone revealed Rush’s usual cleverness: YYZ is the identity code used by Toronto International Airport and the song was written about “coming home”. The meter of the intro was added: it’s y-y-z in the Morse Code that Rush encountered in their own tiny plane when flying back one weekend for a break from Le Studio. It also saw Lifeson add an exotic-Eastern flavoured guitar solo that hinted at the global nature of the band’s travels.

YYZ has become that most unlikely thing. It’s a prog-rock instrumental that does not scream “let’s go to the bar”, but instead is a communal singalong. The footage of Rush playing YYZ in Rio De Janeiro with the old and young crowd going totally apeshit might even convince punks that prog rock is a music that truly breaks down barriers. Muse have covered it as a tribute when the UK trio play Canada.

By coincidence, Limelight was all about barriers. Peart once said, “I didn’t want to be famous… I wanted to be good” and Limelight is all about his reticence about Rush being inside a “gilded cage” amid growing fan numbers. Hence: “I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend.” In many ways, Rush fans are the type that would perfectly accept such sentiment: they didn’t follow the band to rip hems from their clothes, but to simply bask in their musicianship. “If Neil Peart is shy,” they’d have thought, “that is fine.”

It was built on what Lifeson called a guitar riff “so typical of something I would write” and the song structure is typical Rush. It’s in 7/4 – or, more realistically, alternate bars of 4/4 and 3/4 – but drives so steadily it doesn’t sound like it. Rush’s capability to keep complex rhythms fluid was growing.

After the cinematic multi-part starter they’d first pieced together, The Camera Eye, came Witch Hunt, a brooding track that was again somehow prescient. ‘No tolerance for intolerance’ seemed to be the message, with some seeing echoes of Kurt Vonnegut, a writer who Peart knew from his voracious reading. The actual music was something of a studio indulgence, with Peart in particular overdubbing numerous percussion accents and double-tracking his whole kit, and Rush artwork guru Hugh Syme bolstering the banks of synths.

White men can’t dub?

Album closer Vital Signs was easier. Rush wanted something with levity and simplicity and explored the ‘white reggae’ first touched on in the mid-section of The Spirit Of Radio. The trio were under no delusions about their “authenticity” if you will: they’d simply come to love The Police, particularly Lee and Peart. “We were coming at reggae in a more Anglo way, which is how The Police approached it, too,” Lifeson reasoned. “It’s like the way English bands like The Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin worked the blues.” And let’s not forget that Sting’s band themselves were partly a trio of progressive thinking, jazz-chop players dabbling in pop-punk music. That’s even how they first started being interesting.

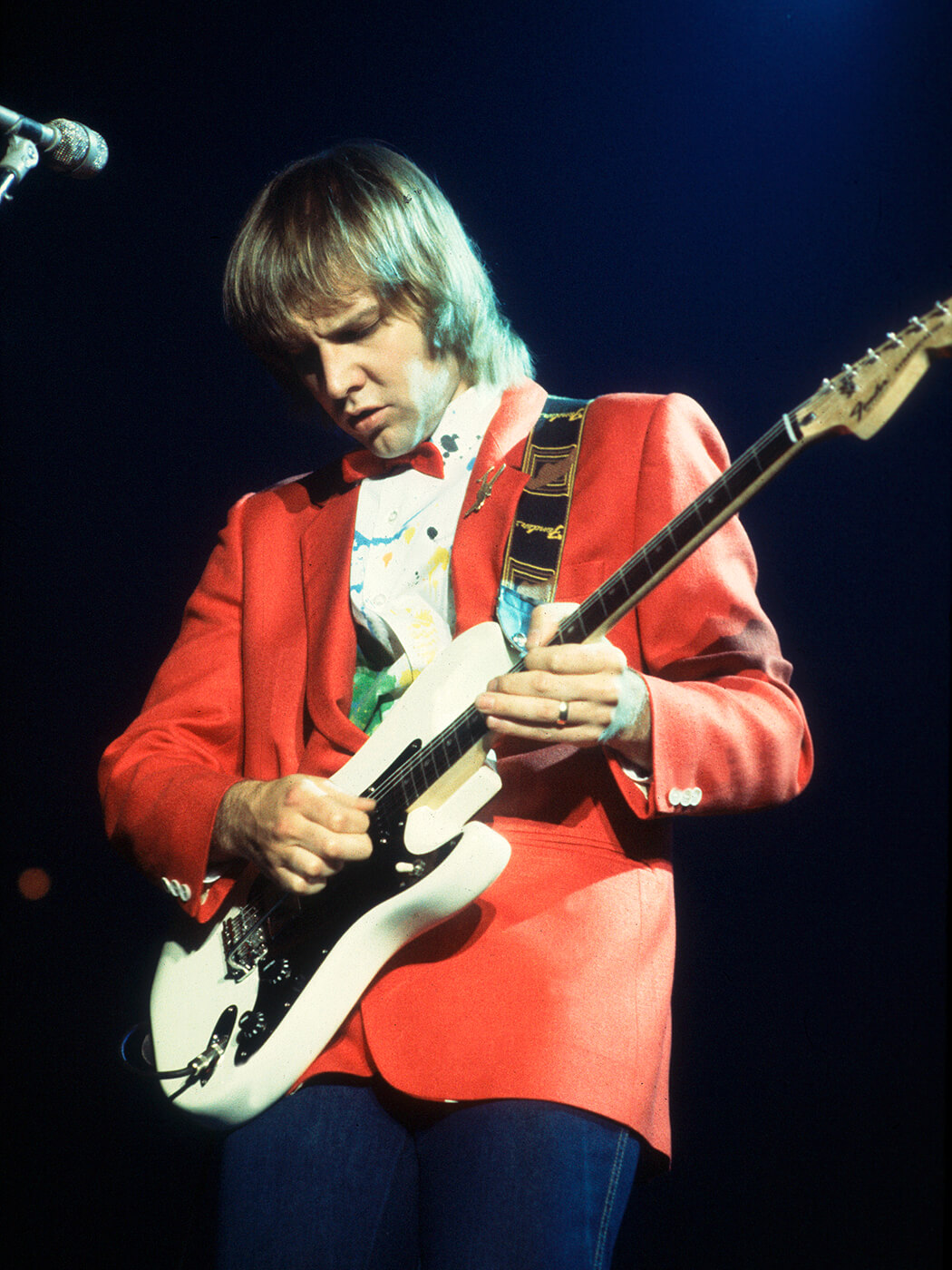

Moving Pictures did involve some new gear, but not much. Lifeson relied on his trusty white vintage Gibson ES-355 (on Tom Sawyer and Witch Hunt) and Howard Roberts Fusion (overdubs on Tom Sawyer) but added three Fender Strats to his arsenal, albeit ones fitted with Gibson PAFs. They allowed the whammy bar solos you can hear, particularly on Limelight. His amps were his usual Hiwatt DR-503 stacks and Marshall Club & Country combos with various pedals (Advanced Audio Digital Delay, Roland Digital Delay, MXR Distortion and Microamp, and LOFT Chorus and Delay). But all the FX were played ‘live’ straight into his backline, as if at a gig. Lee added a Fender Jazz to his usual Rickenbacker 4001, for extra midrange punch. Overdubs were pretty minimal by some prog standards, and Moving Pictures was much leaner, sonically, though that did take time to get right.

Rush fans demanded these songs remained in their live set right until the end. And just as well. Alex Lifeson recently told the Make Weird Music podcast, “Moving Pictures was by far the greatest record that we made. And, from our perspective, we had such a great time making that record. We were in a great space, we spent the summer working fairly close to Toronto… everything about it fell into place.”

Lee later reflected that “people might say it was the birth of modern Rush.” Peart later reasoned, “If Moving Pictures had been our first album, then I’d have been very happy. I sometimes wish it was.”

Blockbuster pictures

Unlike some of the albums in this series, Moving Pictures is no underground secret or undiscovered treasure. It was huge. Of its seven songs, three were hits. But it’s worthy of celebration as it dramatically took an often-derided prog band into the mainstream, yet without compromising what Peart called their “exuberant” elaborate musicianship. Or as Lifeson says, “We want to challenge ourselves every time we play.”

And Moving Pictures was mostly still the sound of Rush as a live trio jamming their asses off: there’s no rhythm guitar, for example, under the solo of Tom Sawyer and YYZ could, inexplicably, be played live perfectly by just the three. Technology was still primitive enough that the bass/keyboard mix was relatively limited by the capability of Geddy Lee’s multi-tasking limbs (ultra high-bar, though they are). The band had a way to go before employing Frankie Goes To Hollywood synth-guru Andy Richards (as they did for later 80s LPs Power Windows).

But that’s why Moving Pictures worked. Moving Pictures captured a moment when Rush moved from one scene to the next… from being a cult prog band to being the planet’s biggest cult prog band.

It’s Manic Street Preachers’ James Dean Bradfield’s favourite Rush record. It’s Mastodon’s Bill Kelliher’s favourite Rush record. It is, by some margin, the world’s favourite Rush record.

Infobox

Rush, Moving Pictures (Anthem/Mercury, 1981)

Credits

- Geddy Lee – vocals, bass, keyboards, Moog Taurus pedals

- Alex Lifeson – guitars, Moog Taurus pedals

- Neil Peart – drums, percussion

Additional musician

- Hugh Syme (cover designer) – additional synth on Witch Hunt

Standout guitar moment

Limelight

For more music reviews, click here.