Related Tags

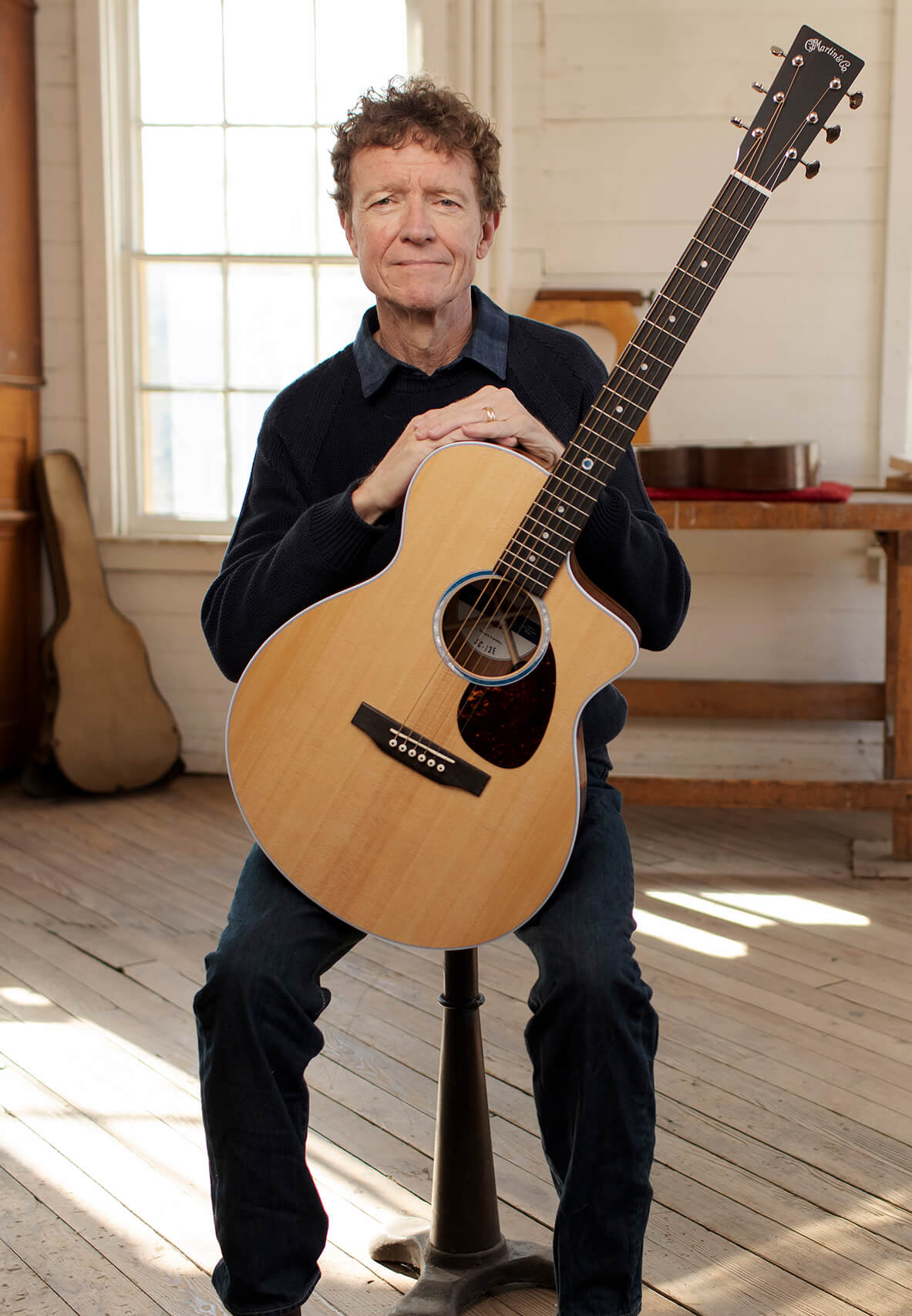

The Industry Interview: Chris Martin IV, CEO of Martin Guitar

The Martin Guitars CEO on heritage, innovation and turning around the fortunes of America’s oldest guitar company.

Image: Martin Guitars

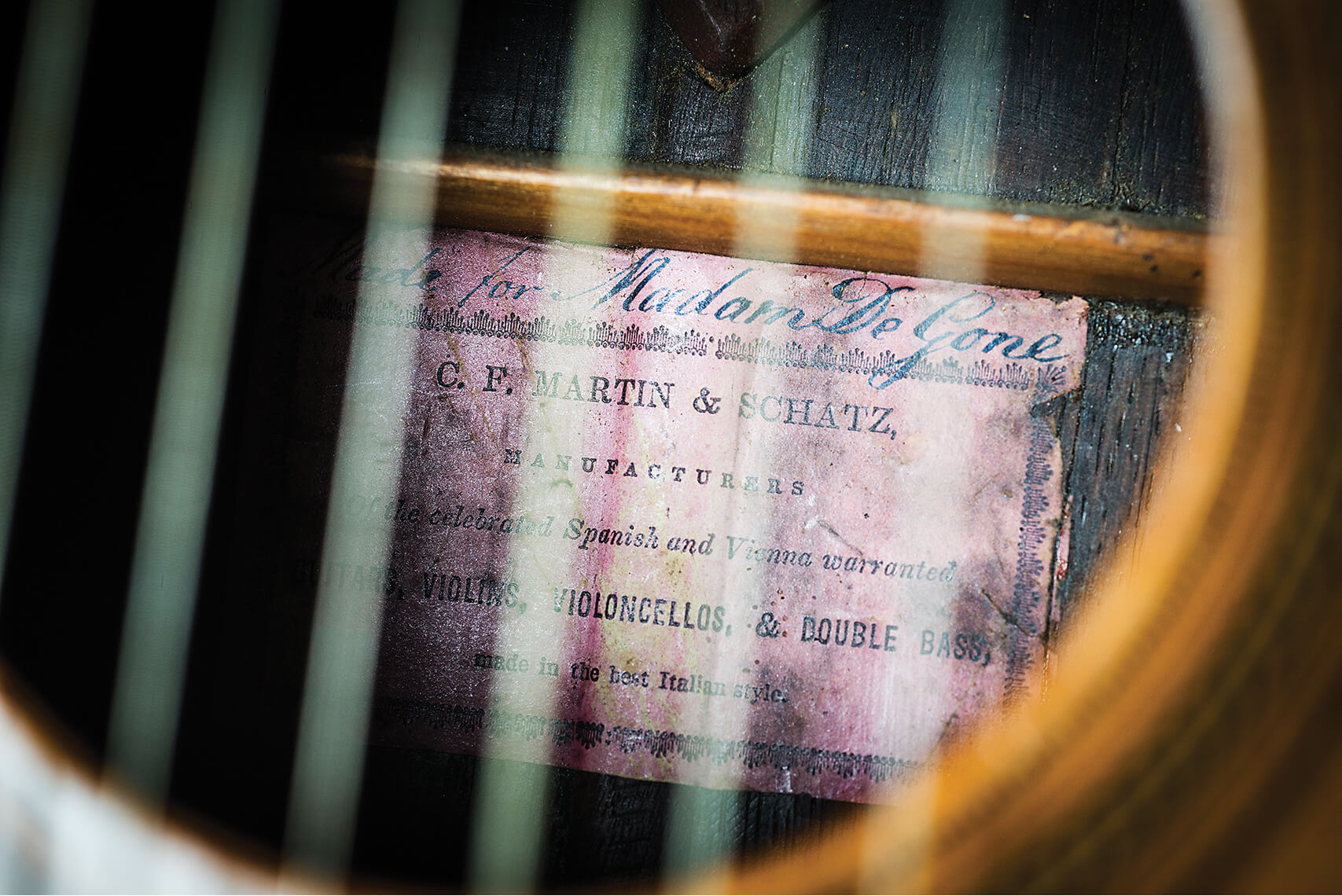

For all their hell-raising, wild living and love of anti-establishment posturing, guitarists can be as besotted with heritage as any card-carrying National Trust devotee – and no brand delivers guitar heritage better than CF Martin & Company. The Nazareth, Pennsylvania-based doyen of acoustic guitars was founded in New York by German émigré Christian Frederick (Friedrich) Martin in 1833 and was one of the pioneers of the steel-string acoustic guitar, which was to become an essential component of popular music throughout the 20th century.

Plenty of other companies came and went during the intervening 187 years but Martin persevered and prospered – though not without a few ups and downs along the way – setting the benchmark against which premium-quality acoustic instruments are measured.

What allowed Martin to climb to the top of the tree and remain there for the best part of 200 years? It wasn’t just product innovation. It’s true that Martin was at the bleeding edge of new developments in guitar-making, such as X-bracing and dovetail neck joints, and once it was perfected in the 1930s, the dreadnought became probably the most copied guitar shape in history.

Similarly, the adoption of the 14th-fret body joint had a significant impact on the sound and playability of the modern acoustic guitar and was once again copied by pretty much everybody else.

What really set Martin apart, though, was quality, both of manufacture and sound – and what ensured both was an uncompromising sense of tradition. Martin remained a family-owned and run business and, however much a hired CEO may love their company and its products, it’s tough to imagine they could feel quite the same way about guarding the Martin name and legacy as does Chris Martin IV, the great-great-great-grandson of its founder, who runs the company today as chairman and CEO.

That isn’t to say that hiring family is a guaranteed way of getting things right. Chris is candid about the strained relationship he had with his father, Frank Herbert Martin, and how it was Chris’s grandfather CF Martin III who rescued the company after questionable decisions and a major union dispute nearly ran the business off the rails in the 1970s. It’s an open secret that grandfather Martin saved the business and mentored Chris, who has been a popular and famously steady hand at the helm since he took over in 1986.

Over the years, Chris Martin has matured into the role of head of one of the world’s most important instrument-makers and is widely admired in the industry. This appreciation recently culminated in his appointment as the chair of NAMM, the prestigious US musical instrument trade association. He talks with a rare candour, his answers free from jargon and buzzwords.

We begin by asking whether he’d always known he would one day work in the family firm.

“No. My parents were divorced and it was a bad divorce. My mum did nothing whatsoever to encourage me to even pay attention to the business. My grandparents though, Mr Martin and my grandmother Daisy, must have recognised that there was a possibility that I would be the next Martin. My father and I had a challenging relationship but my grandfather Martin and my grandmother Daisy would go out of their way to get me to Nazareth for a week or two in the summer, where I was exposed to the business.”

“I was scared to death. Business was tough. I wasn’t a born leader. I was never the president of the senior class”

It was a Californian guitar-shop owner who finally tipped the scales.

“Fred Walecki was visiting the factory and asked if I was going to join the family business. I said that I didn’t know, because, at the time, I was considering going to the University Of Miami to study marine biology. I had this image of scuba diving all day long.”

Walecki put an alternative proposition to Chris: that he should come down to Los Angeles, attend UCLA and work in his music store to give him a taste of the business. “I thought, ‘Okay, what the hell?’” says Chris. “Anyway, UCLA accepts me and I’m working in Fred’s store, and he says, ‘Okay, go sell Martin guitars.’ I told him that I didn’t know how to do that and he realised I didn’t know anything about Martin guitars at all. So he suggested that I go in the back instead and help John Carruthers repair Martins.

“So I go in the back and John, who was the sweetest soul, would give me products and I could see in his face he was thinking, ‘Not only does he not know anything about his family business but he knows even less about how to repair the guitars his family business makes.’ They were so accommodating of this buffoon that they had inadvertently hired.

“Meanwhile, I felt like a fish out of water at UCLA, which had 29,000 students and all of them seemed to look better, drive a fancier car, and have more money than me. I called my mum after two quarters there and I said, ‘I’ve got to leave here. I want to go back and I want to work in the factory and really find out how Martin guitars are made.’

“suddenly MTV Unplugged happened. you’d turn on your TV and there was your favourite rockstar playing your favourite rock song on a Martin guitar”

There was silence on the phone, followed by, ‘What did you just say?!’

Oh boy, she was not happy. My father said, ‘You want to do what?!’ He had never worked in the factory. But my grandfather said, ‘Well, that’s an interesting idea…’”

Chris was put on a fast track. Usually Martin factory workers specialise in a single job but Chris was shown the entire process. “I came away from that experience with a great deal of respect for my colleagues and enough knowledge that I could say I was out there, I knew how they were made. My favourite line is, ‘Unlike Bob Taylor, Chris Martin is dangerous with a chisel.’”

However, all was not well with the company. “It was challenging,” says Chris. “My grandfather and grandmother sent me to the local community college and my mom said I had to go and get a degree, something to fall back on [Chris has a business degree from Boston]. Meanwhile, in that time period, the company was unionised and went on strike.

“This was a dark time. Ultimately, the union disintegrated. But in the meantime, three of the four acquisitions my father had made were failing – buying Darco strings was a brilliant move but Vega guitars, Fibes drums and Levin guitars never made money. Particularly Levin, which became a drag, because we were propping up this really inefficient factory in Sweden.

“The strategy there was that we needed distribution for Martin in Europe and Levin had a sales force, which is what my father thought he was buying. But he inadvertently bought an inefficient factory. Ultimately, the banks started breathing down our necks because, at the same time, acoustic guitar sales had fallen off a cliff – thank you, disco and the Yamaha DX7. My father’s strategy at that point was retirement.

“So now I’m back, working and bouncing around the office, travelling a bit with the elder statesmen sales reps, who would drag me along with them. This was where my fascination with travelling and telling the Martin story began. With my father resigning, my grandfather had to reassert himself – I think he was in his nineties at the time. Then, he passed away, which sent a shockwave through the company, the community and the industry. ‘Frank has retired. CF Martin III has passed away and there’s this kid that nobody knows much about.’

“I was scared to death. Business was tough. I wasn’t a born leader. I was never the president of the senior class. I said to my colleagues, ‘We’re in a bit of a predicament here. The guitar business is bad,’ – we had gone from 23,000 to 3,000 guitars a year – ‘and, oh, by the way, I am bothered by the fact that we have some quality issues.’ And that was what really bothered me: the guitars were not intonating properly and my father and his colleagues had not really been willing to devote the resources to fix the problem.

“I said, ‘Look, if it’s only 3,000 guitars, we’ll try to figure out how to make this business work, and we’ve got to make damn good guitars because that’s what we are.’ That resonated with my colleagues. I heard them say, ‘I never heard Chris’s father say that. I think I heard Chris’s grandfather say it though – and now I’m hearing Chris say it, so I’m going to believe it’s the right thing to do.’

“It wasn’t that big a deal in the end. We fitted a compensated saddle, which fixed the intonation issue. As for sales, suddenly MTV Unplugged happened. One day, Dick Boak, who was doing artist relations and marketing, came into my office saying he’d got a call from MTV. I said, ‘The rock-video station? What are they calling us for?’

“He said they had this crazy idea where they wanted to take famous rockers and get them to play their songs on acoustic guitars. They wanted to do some filming in New York but weren’t sure whether some of these guys even had acoustic guitars or, if they were coming from London or California, whether they would want to bring acoustics with them. They wanted to know if we would lend them a couple.

“I looked at Dick and he looked at me, and we both said, ‘And the answer is…?’ Dick would call them on Mondays and they’d say it would be so-and-so and such-and-such, so he would load up his car with guitars and drop them off in New York. On Saturday nights, you’d turn on your TV and there was your favourite rockstar playing your favourite rock song on a Martin guitar.

“It started out slow but, as the momentum built, that show reminded people just how cool acoustic guitars can be. I give them a great deal of credit for helping my family’s business get back on its feet.”

Bob Taylor played a part too. During the 1980s, Taylor’s formula, which effectively saw his guitars approach solidbody levels of playability (and thus make them more appealing to electric guitarists), had become massively successful, which spurred Martin to make its own guitars more player-friendly. Chris is quick to credit Taylor for that, and tips his hat to his rival’s use of production machinery, which Martin also adopted.

“This year, we’re going to make about 130,000 guitars. If I told my ancestors that, they’d say, ‘Did you say 130,000 guitars in one year?!’ We have the factory in Mexico today, plus a lot more technology – so thank you, Bob, for exposing us to that tech. Bob went to vo-tech school [vocational technical school in the US] in Southern California, where they prepared you to go into businesses that manipulated metal – a lot of aerospace work and R&D stuff. Bob wanted to be a guitar-builder and, since his teacher taught him how to use a CNC machine to cut metal, he was able to apply that knowledge to cutting wood. You’ve got to praise him for eliminating a lot of the waste, and the setup and tear-down that we were doing the old-fashioned way.”

For all that, many Martin lovers are strict traditionalists. Isn’t admitting to using advanced technology a little risky?

“Yes, we can always do it the old-fashioned way and we’re proud of being able to do that. But using machines and tooling has always been in the Martin DNA, it’s just that the sophistication today is lightyears ahead of what was available to my ancestors. If a machine can make us more efficient, we will use it. Remember, no-one has invented the guitar-put-it-together machine yet. Even in Asia, ultimately all the parts of a guitar are put together by human beings and, in our case, I believe we have the most sophisticated guitar-building workforce on Earth.”

As well as efficiency, modern guitar-making technology also offers a higher level of consistency. But Chris admits his more traditionalist customers sometimes pine for the days when every part of every guitar was made by hand.

“People push about that sometimes. They say that, if you look at those golden-era guitars, they were less consistent than guitars are today. If that trips your trigger, good for you, but I don’t think that was my ancestors’ intention. Once they’d developed a model in their minds, I think their next thought was how they could build as many of that model as possible, as consistently as possible. Given the technology they had, they did the best they could.

“At first, when we realised that Taylor had found our Achilles heel, which was playability, we were in denial. Then, the biggest challenge became having a design and a way of building that was pretty much etched in stone, with a huge investment in that process. How could we make the guitars more playable without throwing the baby out with the bathwater? How do we accomplish this Herculean task and have it be transparent to the customer so they go, ‘Wow, it looks and sounds just like a D-28 but plays like an electric guitar.’ Now and again, we get called out on it, though. My favourite is when someone complains about the action on a Martin being too low and I go, ‘Yes! We’ve arrived!’”

Not only did the action sometimes seem too low for the puritan diehards but changing neck profiles caused some problems too. “Where we got pushback wasn’t so much with the height of the string off the fret, it was a combination of that and re-profiling the neck. ‘This neck’s too skinny. I like the old baseball-bat neck.’ We had a period when we did both and we still will. We’ll make you a vintage reproduction. We’ve taken vintage guitars from our collection, put them on a granite table and probed them with a hook-up to a computer that says, ‘Okay, now I understand what the shape of this neck is,’ and you send that to a CNC machine and it carves the neck just like it would have been carved with a draw knife in 1937.”

Given that Chris and his team put so much effort into making the Martins of today, we wonder whether the company’s CEO ever gets tired of the ‘golden era’ mythology that surrounds the Martins of the 1930s.

“Let’s put this into perspective. Even in the 1930s, we were still learning how to make guitars in quantity with steel strings. It was only 10 years earlier that they had gut strings. I think there was a lot of, ‘Let’s try this and see if it works,’ so it varies. We’re also offering a lifetime guarantee, don’t forget, so they can’t self-destruct in the field.

“Now, the sound that a fine instrument makes lies somewhere between it holding together for as long as you own it and, at the same time, being on the verge of self-destruction, wanting to tear itself apart. That’s where the sweet spot is. I’ve seen overbuilt guitars that only look like a guitar from 10 feet away. They may even play okay but you can tell there’s a lot of sound dying to come out of it that never will.

“I believe that guitars that have been played for 50 or 60 years have an advantage over new guitars. I tell people that their new guitar will sound better in 50 years and they ask if that’s a guarantee. I say, ‘I guarantee, if you take that guitar and put it under your bed, it won’t sound as good as if you’d played it.’”

The heat treatment of timber has made an important difference, says Chris, as has the accuracy afforded by modern manufacturing. But, it turns out, there’s torrefaction and then there’s torrefaction.

“I’m a layman but, as I understand it, something happens to the wood over time that torrefaction can make happen much, much faster. My colleagues have spent a lot of time on this and yes, you can over-torrefy wood. Our feeling is that we’ve dialled it in so that we’re taking that top back to the 1930s. Leave it in the kiln too long and you could take it back to the 1830s – and that isn’t what we’re looking for.

“I’m frustrated that whenever I push us to embrace using alternative materials, the traditionalists push back”

“I get the impression that a lot of people throwing around the term ‘torrefaction’ are tossing wood in the kiln, crossing their fingers, pulling it and saying, ‘Yep, it’s torrefied!’ But we’re trying to achieve something specific when we torrefy wood.”

While the sense of tradition that surrounds Martin motivates Chris in his drive to keep the company successful, it can also be a drag on some of the things he would like to do, as he reveals when we ask about the prospect of Martin using new materials, particularly as high-quality tonewood becomes more scarce.

“I’m frustrated that whenever I push us to embrace using alternative materials, the traditionalists in the marketplace push back – and they really push back. I still get a lot of pushback on the high-pressure laminate guitars, the Stratabond neck and Richlite fingerboards. I tell them that it’s still wood, it’s just wood that comes from a farm. They say it’s not wood, it’s plastic. But it’s not plastic – stop!

“I’m seeing some of the smaller luthiers changing things by saying that I’m moving on and making guitars out of new woods. Maybe that’s where the trickle-down will come. The customers will change as they see individual luthiers giving alternative woods their blessing. They’ll say, ‘Maybe I will allow Chris to use it on a Martin.’ I love that they love the company, its history and its traditions, but they sometimes think they’re more responsible for the company than I am. I have to make a decision that I think is the right one and it isn’t always by consensus. If I did it by consensus, we’d be making just three Brazilian rosewood guitars a year!”

When Chris becomes a historical figure in the Martin narrative, he will no doubt be seen as one of the great Martins – a man who started from a near standstill and steered the business through its biggest period of growth; a man who pioneered new manufacturing techniques and new styles of guitar but who, above all else, ensured that modern Martins are as prized as they’ve ever been.

It should be noted by future historians too that, despite the crushing pressure of familial legacies and customer expectations, he remained an approachable, honest and likeable human being.

Check out other features and artist interviews here.