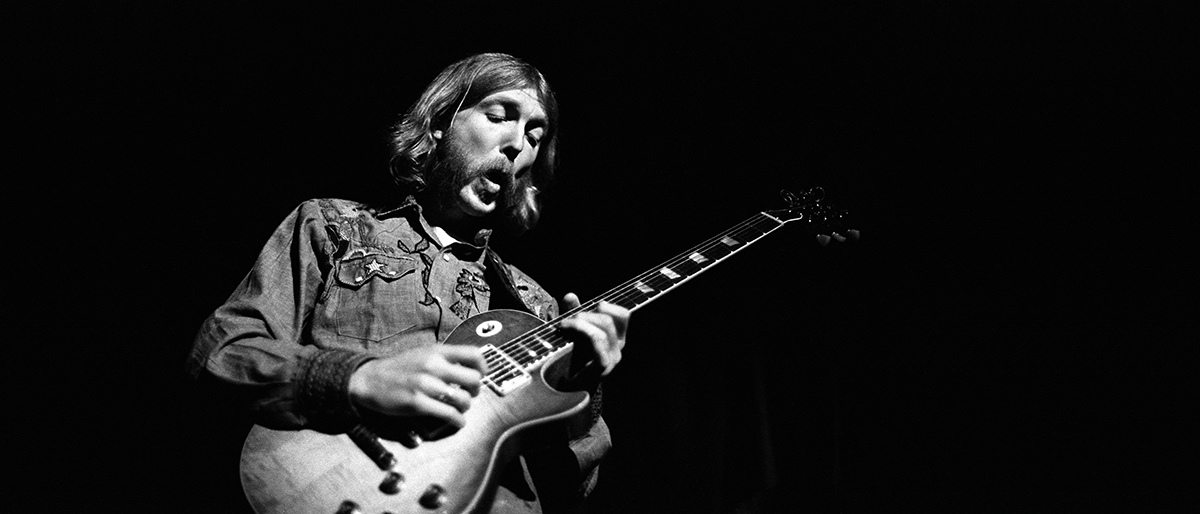

Duane Allman: The guitar legend’s life in music

Slide supremo. Blues maestro. Jazz improviser. Bandleader and “mothership”… Duane Allman was all those things. Skydog boxset producer Bill Levenson and Duane’s daughter Galadrielle help guide G&B through a dazzling document of guitar genius, now available in 14-album vinyl format…

When any talented artist dies young, it’s usual to ask: what might have been? In the case of Duane Allman, who died in 1971 – a year after Jimi Hendrix, yet three years younger – it’s been the opposite. If anything, the passing of time has peeled back the multiple layers of what Allman actually achieved in his brief 24 years. By any measure, Allman’s recordings for one so young were astounding.

After years of false starts, Allman’s recorded legacy came together with the release of the CD boxset Skydog in 2013. A critical and commercial success, Skydog is back again, this time in appropriate vinyl form. Even at 129 tracks, it’s not nearly comprehensive, and for executive producer and lauded rock ’n’ roll archivist Bill Levenson, it has been a labour of love.

“There have been other Duane Allman packages, of course,” he notes. “The Capricorn two-LP sets which, at the time, seemed massive packages but now seem modest. And the chronology didn’t matter so much on those. We’ve gone back to the first Duane Allman recordings we could find. Chronology is important on Skydog.”

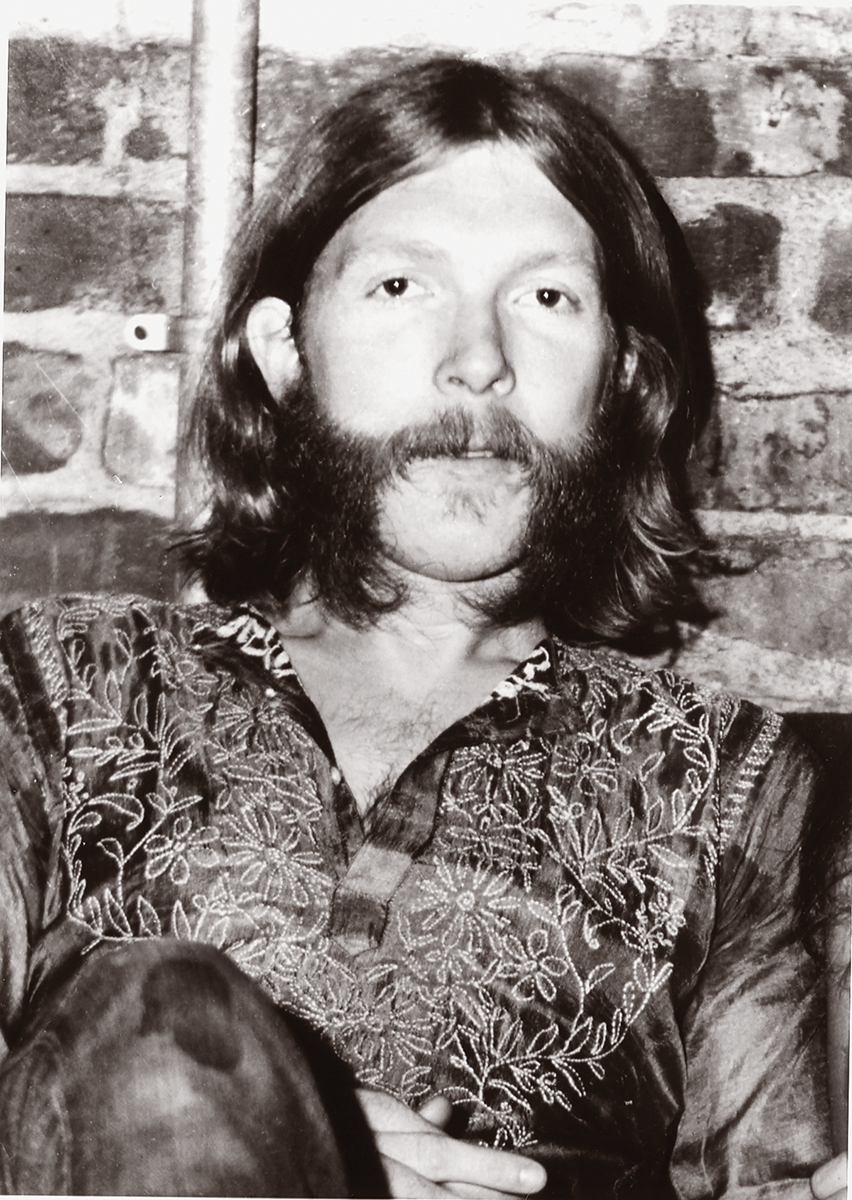

Levenson was soon joined by Allman’s daughter, Galadrielle. For her, the work was bittersweet. Galadrielle Allman never knew her father – Duane died when she was just two – though her detective work was to culminate in her own biography of Duane, Please Be With Me. In the Deluxe Edition boxset of Skydog, you get 14 vinyl albums and her book, signed.

“In some ways, Bill and I came separately to the table,” she says. “I was the one charged with sourcing the photographs and writing something. But I also had a say in the music in a way that I didn’t anticipate. That happened in the home stretch of writing my book, and it really helped. Just to have all the chronological tapes from my dad’s life there was a huge gift. It was a more vast well than I originally thought.”

Beyond the Brothers

Skydog works so well because it treats Allman’s work outside of The Allman Brothers Band not just as a diversion. The Allman Brothers Band tracks, just 21 of 129, arrive towards the end of the road trip. Before then, there’s Duane playing spidery R&B guitar in teen band The Escorts, mimicking The Yardbirds in The Allman Joys, marrying psychedelia and blues in Hour Glass, short-lived band The 31st Of February, plus killer contributions on sessions for Clarence Carter, Wilson Pickett, Laura Lee, King Curtis, Aretha Franklin, John Hammond and more. There are three self-sung tracks from Duane’s incomplete solo album (never released), plus blazing guitar sparring with Otis Rush, The Grateful Dead, Boz Scaggs, Delaney & Bonnie and, of course, Eric Clapton.

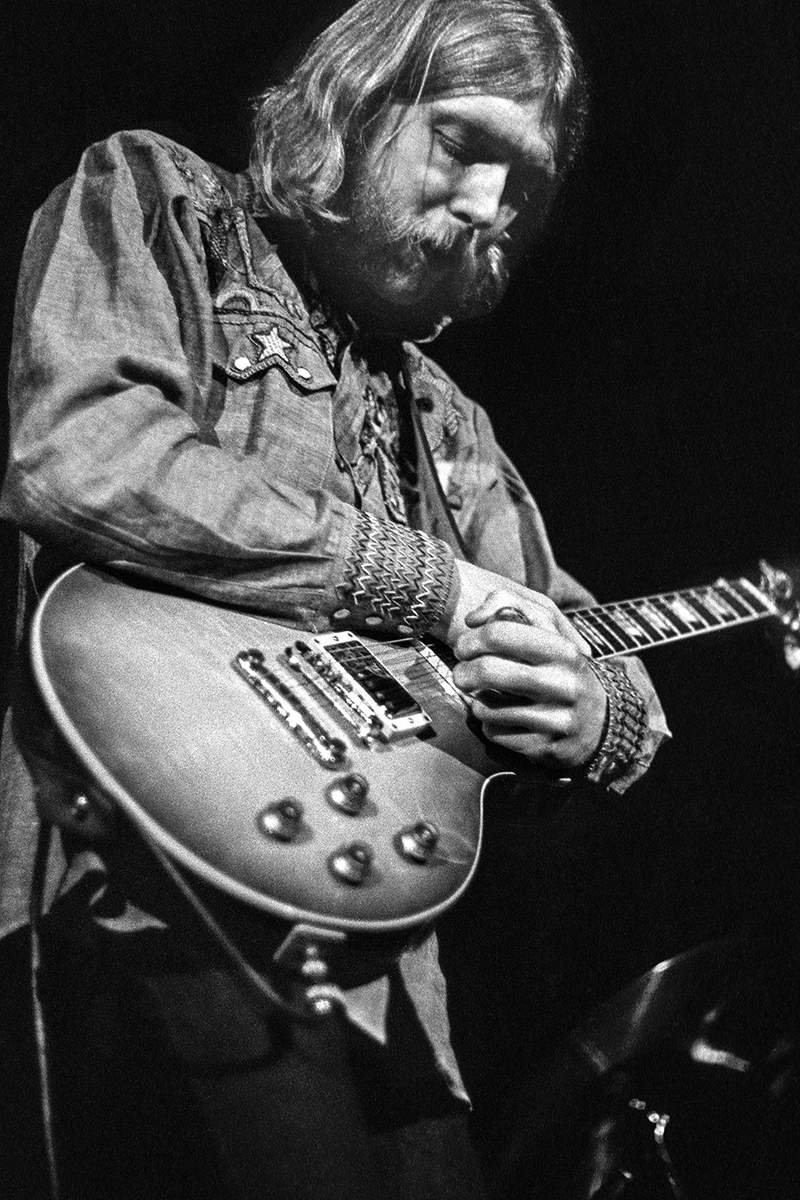

Allman’s studio sessions are where you get a real perspective on his talent. Other guitar greats, such as Hendrix, Page, Beck, Clapton et al, may be well served by live albums and collections of various jams, but none really had a sideman career quite like Allman’s.

And these aren’t mere offcuts: they are pro recordings, often at Muscle Shoals, for a slew of great 60s records and artists. Lesser-known cuts are instructive, such as Scaggs’ epic Loan Me A Dime, with heavy Hammond organ and signature Allman slide guitar to the fore like proto-Allman Brothers…

And these aren’t mere offcuts: they are pro recordings, often at Muscle Shoals, for a slew of great 60s records and artists. Lesser-known cuts are instructive, such as Scaggs’ epic Loan Me A Dime, with heavy Hammond organ and signature Allman slide guitar to the fore like proto-Allman Brothers…

“That’s the right spot,” opines Levenson. “The first Allman Brothers album was September ’69, the Boz Scaggs tracks were Spring ’69, so it’s a key time.

“And what you hear is that acceleration! From doing the soul sessions to The Allman Brothers, Duane finds the guitar voice we all know very quickly. I hear a confidence that just explodes. It goes on into 1970, with the Allmans’ Idlewild South album, the Layla… album… by this point, Duane’s not ‘channelling’ anybody, he’s got his own style, his own personality. It’s pretty extraordinary.”

Galadrielle Allman, too young to even remember herself, adds: “It’s easy to forget how young he was, how quickly all of this happened. Between his first recordings and the last, it’s an incredible world of growth.

“He really dipped into every genre of American music by the time he was 20, which I think is quite remarkable. In that way, he wasn’t just a rock player. It’s hard to imagine now that just being in this small, regional recording studio in Alabama brought him into contact and playing with everyone from Aretha Franklin to Boz Scaggs. It’s like he went up the crossroads!”

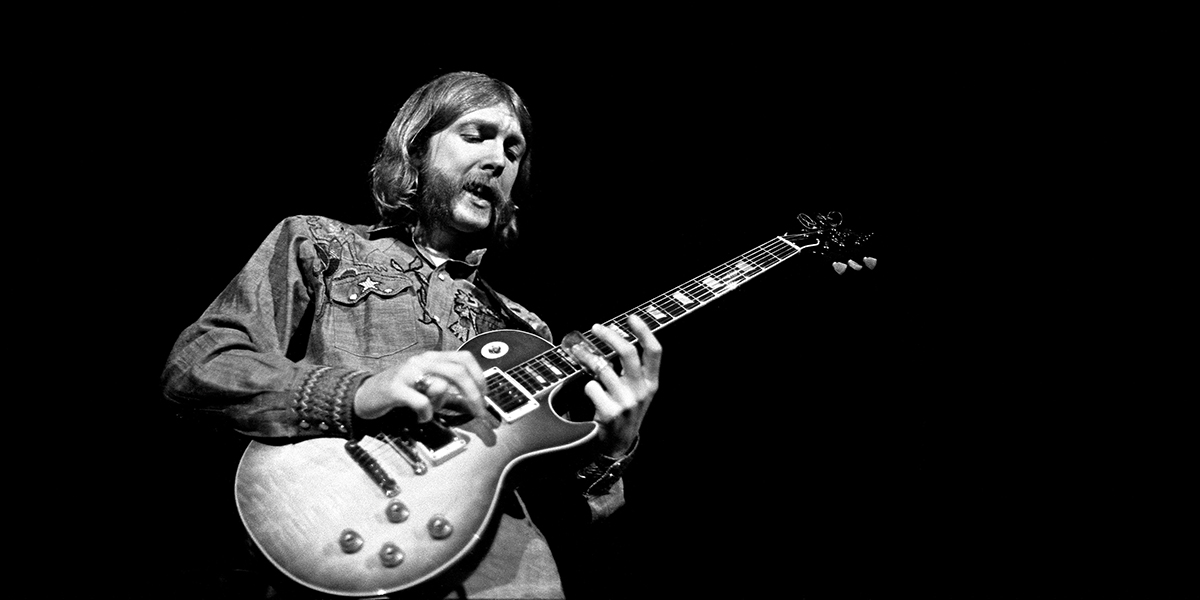

Speaking to Allman aficionados, this is a recurring theme. Not just that Duane was good, but he was good very quickly. “People talk about a career progression over years these days,” smiles Levenson. “Here, you’re talking about six, nine months? I can’t think of any other artist who invents, reinvents, a guitar style in that short period of time. It’s quite extraordinary.

“Maybe the only other guy was Hendrix. You don’t see that kind of phenomenon anymore, I agree. You look at Hendrix, 1965 to ’66 to ’67, and you see it happen. You could probably do so with Jimmy Page, from The Yardbirds into Led Zeppelin. I think you can hear it with Eric Clapton, from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers to Fresh Cream to Disraeli Gears. The Beatles and George Harrison, too, of course. And again, you’re talking months, not years. Quantum jumps in such a short timeframe.”

At the risk of actually saying, “Things ain’t what they used to be…”, it’s noticeable that all the guitarists Levenson cites, including Allman, flourished between the mid-60s and 1970. Does Levenson have theories as to why?

“I don’t know,” he admits. “I don’t want to be flippant and say it was drugs, because I don’t think it was. I just think the music of that time, mid/late-60s, was just so fresh. There were no rules. Everyone was making it up as they went. It’s much harder these days, when there’s an awful lot of people behind you who’ve already established guidelines, tones, ‘rules’, whatever…”

“I don’t know,” he admits. “I don’t want to be flippant and say it was drugs, because I don’t think it was. I just think the music of that time, mid/late-60s, was just so fresh. There were no rules. Everyone was making it up as they went. It’s much harder these days, when there’s an awful lot of people behind you who’ve already established guidelines, tones, ‘rules’, whatever…”

In researching the biography of her father – who split from her mother early on – Galadrielle soon found that everyone close to Duane talked of an incredible work ethic. “The only way he could have had that kind of output is because he never stopped. While the other guys were resting, he was out there jumping from one thing to the next. Some people may have painted him as some sort of lackadaisical hippy, but that so was not the case. He was a hard-working prodigy, truly.”

Skydog: best in show?

With so many tracks, Skydog isn’t going to be for everyone: “There are some choices in here that are for completists, no question,” admits Levenson. And to feature as much of Duane’s story as possible, the producer even committed to some tracks without previously hearing them, “Because we believed they’d progress the storyline.”

An example is Allman’s three 1968 tracks with The Bleus [sic], despite the name a shortlived psych/beatpop group, aside from a few tasty Duane fills and one nice slide solo. “They’re not as Duane Allman-centric as we’d like,” says Levenson, “but they filled a niche and help tell the story. With 130 tracks, not every one is gonna be a stone-cold classic.”

That said, most of these sessions are superb, and not just the barnstormers such as Wilson Pickett’s Hey Jude. “The Delaney & Bonnie outtake of Gift Of Love, I found it unbelievable that was unissued,” Levenson says. “There was another version released, but not this one. Gift Of Love was actually going to be the title of the Skydog boxset for a while.

“Another one is Delaney & Bonnie & Friends… the Poor Elijah/Tribute To Johnson medley, the live track, is incredible. Not just Duane, but everyone included. That captures a moment in time, where people just collaborate on the spot and come up with something amazing.”

And the Allmans are, of course, well represented. Both Levenson and Galadrielle Allman point to a live version of You Don’t Love Me, which segues into King Curtis’s Soul Serenade, recorded just weeks after Duane had attended the funeral of the jazz saxophonist and mentor. “They were really good friends and my dad learned so much from him,” says Galadrielle, “he couldn’t say enough about what he learned from Curtis about improvising.”

“Curtis would have been on Duane’s mind,” concurs Levenson, “and to be able to step in front of an audience and pull out Soul Serenade like that… incredible.”

“Curtis would have been on Duane’s mind,” concurs Levenson, “and to be able to step in front of an audience and pull out Soul Serenade like that… incredible.”

If nothing else, Skydog lays to rest the notion that Duane Allman was ‘just’ a Southern rock slide player. Brother Gregg Allman has often argued the tag is daft anyway, as most of the Allmans’ heroes – Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry – were Southern anyway. “Saying ‘Southern rock’ is like sayin’ ‘rock rock’!” Gregg once jibed.

“When I was a teenager, I was listening to punk!” laughs Galadrielle, who grew up in California, “but when I was in college in New York I would hear Allman Brothers music out of dorm windows of 20-year-olds. Part of me believes that The Allman Brothers are identified with the South in such a regional way, it actually does them a disservice.”

That much is true. It’s all music. And as Skydog attests, all music is something that Duane Allman made his life’s mission – no matter how brief that life was. As Duane himself said in a rare interview for a promo album called Duane Allman Dialogs: “There’s a lot of different forms of communication, but music is absolutely the purest one, man. You can’t hurt anybody with music. You can maybe offend somebody with songs and words, but you can’t offend anybody with music – it’s all just good.

“There’s nothing at all that could ever be bad about music, about playing it. It’s a wonderful thing, a grace.”