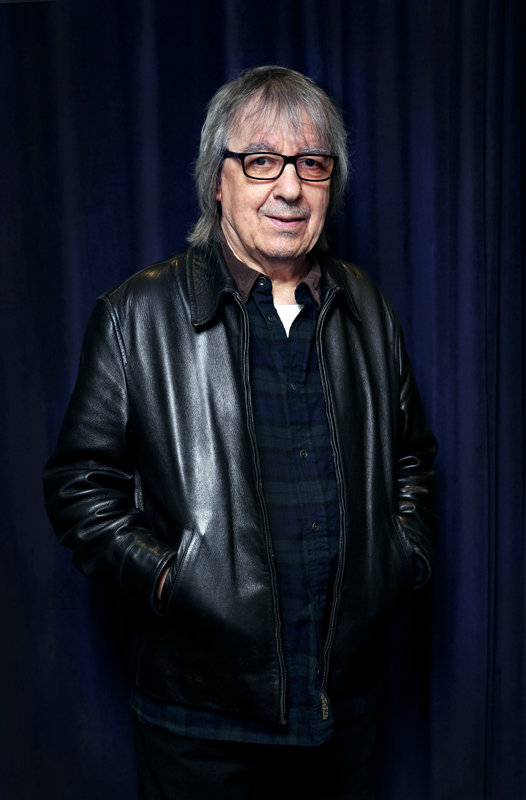

Interview: Bill Wyman on his musical beginnings

Rhythm King and ex-Rolling Stone Bill Wyman thrums bass and takes lead vocals on Back To Basics – a long-awaited return to solo work.

Since his amicable departure from The Rolling Stones in 1993, Bill Wyman has been most conspicuous as founder of The Rhythm Kings, a flexible amalgam that he compares to “a football team – if someone gets injured or is called away to something more lucrative, we bring in a substitute.”

Some gifted personnel appear on Wyman’s new album, Back To Basics – only his fifth solo offering – executed as proficiently as you might expect by musicians of the calibre of guitarists Terry Taylor – a Wyman accomplice for decades – Guy Fletcher (ex-Dire Straits) and former Paul McCartney sideman Robbie McIntosh. Other players to pass through the ranks of The Rhythm Kings have included Albert Lee, Andy Fairweather Low, Mark Knopfler, Mick Taylor, Eric Clapton, George Harrison and Peter Frampton – known to Wyman since 1964.

“He was 14 then,” remembers Wyman of his first encounter with Frampton, “and about to join The Preachers, who evolved from The Cliftons, the group I left in order to join the Stones. He replaced my friend Steve Carroll – with whom I first started to play music, when we were both clerks in a south-east London department store.

“Steve was a magical guitarist, who could hear a Chuck Berry riff once and just play it straight off. He died in a car crash in 1964, three days into the Stones’ first tour of the States. Andy Bown, who was in The Preachers and then The Herd with Peter, reckoned Steve was ‘the greatest guitar player the world never heard’.”

Long before he teamed up with Carroll, it had been Wyman’s fancy – unspoken at first – that he’d like to make his way in the world as a professional musician. “It became my ambition when my aunt took me to a dance in 1946 when I was 10,” he recalls. “She did the jitterbug with an American soldier to a big band, but it seemed far-fetched to imagine I’d ever be in one – because they were all trained musicians, who’d practised six hours a days for years. Yet I did have piano lessons, and passed a few Royal College of Music exams.”

Nevertheless, Wyman entered the world of work as a bookmaker’s clerk, a job that lasted until the dreaded envelope that hung like a sword of Damocles over every young Englishman landed on the doormat one morning in 1955. The War Office, anxious about the deadlock the Geneva Summit had reached over the reunification of Germany and a correlated abandonment of east-west defences, sent for Wyman. When posted to the British zone of a still-occupied Fatherland, how could Wyman have known how fateful it was to purchase for a few Deutschmarks an acoustic guitar with taut strings so high off the fretboard that barre chords proved painful to the as-yet uncalloused fingers on his young hands?

“I also heard the beginnings of rock ’n’ roll on American Forces radio,” he says. “Back in England, a couple of months before I was demobbed, I formed a skiffle group with another serviceman, Brian Cassar – Casey Jones – a Liverpudlian who came to know The Beatles. Later, he was in Casey Jones And The Engineers, which had Eric Clapton and Tom McGuinness in briefly.”

On returning to civvy street in 1958, Bill was moonlighting from his day job as a Clifton. He spent what amounted to six weeks’ wages on a Burns electric guitar and, after a period of feeding it through a tape recorder, a state-of-the-art Watkins Westminster amplifier. As the combo’s ‘bass player’, he tuned his instrument down and, on one occasion, wound bass strings onto it. Then came a ‘road to Damascus’ moment during a weekend he spent with relatives in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. On the Saturday, they’d attended a bash by a local combo, The Barron Knights. “All I remembered about it was the power and fat sound of Barron Anthony’s electric bass, the first time I’d ever heard one. That was what was missing in The Cliftons,” says Wyman.

Wyman’s appetite for catering was not dampened by the ultimate failure of The Brasserie – as evidenced by the opening of his Sticky Fingers diner in London, despite awareness that “Five restaurants had failed on that site before, but we’ve won all sorts of awards since, and Sticky Fingers is now on a par with the Hard Rock and Planet Hollywood.”

So it was that the gear loaded onto the group’s van was to include a 30-watt bass amplifier built via instructions in Radio Rentals magazine. It was combined with a coffin-like cabinet with an 18-inch Goodmans speaker – and a concrete base that, supposedly, thickened the tone, but also cured its inclination to creep forward or even keel over on rickety stages. This energised a second-hand instrument of indeterminate make, customised by Wyman, chiefly by the removal of all the frets. “It was the first fretless bass ever,” he says, “years before their commercial manufacture.”

A further indication that Wyman meant business was his purchase of a spare amplifier – a Vox AC30 – as insurance against it being needed should the home-made one fall silent on, say, that nights-of-nights in 1962 when the group had a brush with fame as accompanists to Dickie Pride, a diminutive one-hit-wonder, whose onstage convulsions had earned him the nickname ‘The Sheik Of Shake’. That and a support for The Paramounts (later Procol Harum) were the twin peaks of The Cliftons’ two-year career, during which they were otherwise not much different from any other act in virtually any town in the country who traded in classic rock and current hits.

“Until I joined the Stones – on 7 December, 1962 – I didn’t know much about blues,” Wyman admits. “I’d never heard of Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley and artists like that, mainly because you never heard them on the radio, or were able to buy their records. I’d come across Josh White and Big Bill Broonzy, but regarded them more as folk singers. However, I soon became as fanatical about blues as Mick [Jagger], Keith [Richards] and Brian [Jones] were already – though I still stayed fond of rock ’n’ roll. It was through me, for example, that the Stones did Eddie Cochran’s Twenty Flight Rock much later on.”

The rest, as they often say, is history – and, following the release of Come On, the Stones’ maiden single, Bill was sucked into a vortex of events, places and situations that hadn’t even belonged to speculation when he was a Clifton. If the tourbus had drawn up outside a stadium on Pluto, it mightn’t have seemed all that odd.

Vox cajoled Wyman into endorsing its Teardrop model, even calling it ‘The Wyman Bass’. Yet he admits now, “I didn’t like it. It had my name on it, but I wasn’t consulted about the design. I also played a see-through Plexiglass Fender Mustang for a while but, again, that was a bit too big for me. That’s why I held it vertically – because that’s the only way I could reach the frets.”

It was, however, the Bill Wyman Signature Bass, constructed by London’s Bass Centre, that pulsated when Bill reunited with the Stones at the capital’s O2 Arena for two nights only in November 2012. It remains the instrument he employs in The Rhythm Kings, and it’s also to the fore on Back To Basics, which finds the legendary bass man in complete command of his artistic faculties, with certain of its selections – instanced by the ‘November’ slice of his autobiography and I Got Time, a blues transported by time machine from the 1930s – among the finest compositions in his catalogue. Certainly, the album needs no association with famous friends, past and present, to enhance its intrinsic worth.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Among Bill’s various charitable work from the 1980s onwards has been the shouldering of much of ex-Small Faces bass player Ronnie Lane’s load in organising galas in aid of Action For Muscular Sclerosis (ARMS), initially as one of a ‘supergroup’ at a Royal Albert Hall fundraiser. Further such spectaculars hinged on a more fixed set-up: guest players round a nucleus of Wyman, Charlie Watts, Chris Rea and Andy Fairweather Low as Willie And The Poor Boys. In a half-hour in-concert video of the same title, Ringo Starr appeared in a cameo role.

He and Wyman also launched a Beatle-Stone business liaison via joint investment in a restaurant in Atlanta. The official launch of ‘The Brasserie’ in 1986 concluded with a jam session in which the Englishmen presided over the oddly-matched roisterings of Jerry Lee Lewis, Isaac Hayes and Jermaine Jackson.