Interview: Mark Flanagan – Jools Holland’s guitarist

An encounter with Jools Holland led Mark Flanagan into a remarkable career as part of the TV star’s Rhythm and Blues Orchestra, playing alongside some true musical greats…

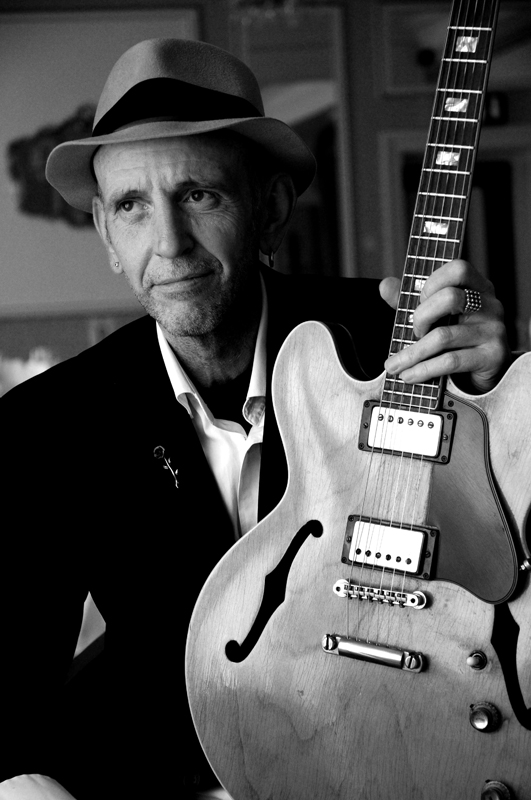

If you’re tuning into boogie-woogie maestro Jools Holland and his Rhythm And Blues Orchestra this New Year’s Eve – rocking out of 2015 with his annual Hootenanny TV extravaganza, take a peek over his shoulder. You’ll see a guy in trendy threads with a snazzy brim – oh, and a rather cool 60s Gibson ES-335… that’s Mark Flanagan.

Born in Liverpool, and influenced from an early age by Edward Flanagan – his guitar-playing dad – Mark honed his skills on the ukulele before moving onto six strings. Following excursions with Little Ginny and later The Box Brothers, a 27-year tenure with Holland has further broadened Flanagan’s playing expertise.

Having backed up artists ranging from Tom Jones to Ellie Goulding and Buddy Greco to Ed Sheeran, Flanagan can slip into the styles of Charlie Christian, Django Reinhardt, T-Bone Walker or Chuck Berry, playing whatever’s needed to suit his band leader.

When that band leader is Jools Holland, you can expect a selection from Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, Glenn Miller, BB King and Solomon Burke. His studio credits include playing with George Harrison, whom he describes as “memorably melodic” on the former Beatle’s final solo album. He’s also an accomplished Dobro and acoustic player – having released several albums under his own name.

Holland speaks highly of his long-time guitar player: “Mark plays little figures that fit perfectly with my busy left hand – he’s the first person I’ve known to do it,” he says. “Mark understands everything from jump-jive to modern music – he can swing, then rock it… Eric Clapton describes Mark as a truly great guitarist.”

Flanagan thanks his dad for setting him on the six-string path: “I was very fortunate, because my dad played guitar; and like a lot of men from his generation in Liverpool, he went to sea in the late 40s and 50s. He bought a lovely dance band guitar in Australia – which I still have, and have just had rebuilt by guitar maker Martyn Booth.

“In the mid-60s, he came home with a ukulele. My brother and sister didn’t really bother with it – but I stuck at it – and we played together for the next three or four years, until I was 12, when I got my first real guitar. It was a Barnes & Mullins flat top – with a DeArmond pickup attached. We would play or practise three or four times a week – old favourites like Who’s Sorry Now or Ain’t Misbehaving. My dad was very encouraging – and very patient. All the family would join in with three-part harmonies, and that ‘musical sense’ was all around the house.

“He told me about open E tuning when I was only about 13 or 14 – and how to play slide. I thought it was interesting, but didn’t really look at it again until 30 years later when I bought a Dobro.”

“I noticed when I was playing with him on ukulele, the same chords were popping up – but in a slightly different order… like the same game, but on a different field. He also talked to me a lot about phrasing – and said I should listen to the likes of Frank Sinatra if I wanted to know how to sing. I didn’t really worry about keys from then on – the patterns sort of joined up for me, so when I changed to guitar I knew where I was already. I used to watch George Formby doing the ‘scissors’ thing and I tried to play like that – but it was 40 years later when Joe Brown showed me how to drag the thumb across the strings, to get that syncopation. I still can’t do it!”

“My dad used to bring records back from overseas, too. I heard Hank Snow, Hank Williams and Hank Thompson – all the Hanks – on 78rpm discs! When I got my guitar – a B&M Country King – that was the music I cut my teeth on in terms of playing rhythm, because obviously I couldn’t get near ‘the master’ [Django Reinhardt]!”

Growing up in Liverpool saw the young Flanagan being surrounded by influential music. “I went to see A Hard Day’s Night when I was about six years old,” he recalls. “I was astonished at all the girls screaming. I missed out on the Merseybeat era in a way – so I was listening to a lot of country music by the time I was starting to play with bands in the mid-70s.”

“Kenny Johnson and Northwind and The Hillsiders were big in Liverpool at that time. I was playing with Little Ginny during that period – we played the big Mervyn Conn country festivals at Wembley or Brighton a couple of times. That was the first time my father saw me on the TV. There was a close-up of the fingerboard for a few seconds – dad recognised the ring I was wearing and shouted ‘that’s our Mark’s hand!’.”

“We were listening to The Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Asleep At The Wheel, and all the people doing Western Swing. For me, it tied in with the Django thing – his swing and the country influence of ‘the Hanks’.”

“I wasn’t really old enough to see or appreciate The Cavern-era Merseybeat bands like the Clayton Squares and the St. Louis Checks, but I was aware it was a great time in Liverpool.”

The Jools Holland job has brought Flanagan into contact with some of his musical heroes. “One of the reasons I got Gregg Allman to sign the back of my guitar is because he came in to do a radio show with Jools when we [the rhythm section] were there in the studio,” he remembers.

“He was just chatting with Jools, when I realised what a real legend he was. I used to listen to The Allman Brothers when his brother Duane was alive and played the slide and all that. Everyone had an Allman Brothers album! I occasionally ask people to sign things – especially if they’ve been an influence on me.”

“There’s Ry Cooder, Little Feat with Lowell George – and the New Orleans stuff like The Meters and Dr. John. But on the playing side, it’s difficult because there are so many great players around! There’s Eric Clapton and Danny Kortchmar, Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter and a bunch of West Coast players like Waddy Wachtel with Warren Zevon, and David Lindley with Jackson Browne… oh and Rory Gallagher.”

“You couldn’t grow up in the 70s and not be touched by his playing. From the reggae world, there is Ernest Ranglin and I enjoy Al Anderson’s work with The Wailers. Of course, there’s the ‘Three Kings’. It was a real thrill when BB King played on Hootenanny – memorable.”

The move to London and initial meeting with Holland came about through Flanagan’s work with Little Ginny, and a busking stint in Edinburgh secured the Jools gig.

“Playing country with Little Ginny, we did a festival in Brighton and met up with The Hank Wangford Band – and became good friends with Paul Fitzgerald. He said if we were ever up in Suffolk to look them up. We played lots of gigs in Lowestoft and the Suffolk area, and I really liked the place – so moved there to live. Then I moved to London – met Jools, and lived there for 15 years.

“I’d started a group up in Suffolk called The Box Brothers with Paul and Delphi Newman; we met up with a London-based theatre group called The Greatest Show On Legs – and we did a lot of shows together with Martin Soan and comic legend [the late] Malcolm Hardee. It transpires that Malcolm had a room in Greenwich – and who lived across the road? Jools Holland.

“Later on, Delphi and I had a duo called The Music Lovers, so we linked up with Malcolm and went to Edinburgh to do a three-week stint. We provided the music and Malcolm did his comedy slot. In the evenings, Delphi and I would go busking, and that’s when Jools saw us.”

“He was filming with Muriel Gray for the BBC at that time, and I think he was quite taken with Delphi’s style of singing and my swing guitar playing. Halfway through our stay in Edinburgh, Jools’ sax player had to return to London to fulfil another commitment – so Jools invited me to fill in, and we’ve been together ever since.”

Flanagan recalls late-night big band record listening sessions at Holland’s house – taking note of what the guitar player was doing in the background – often a repetitive riff of four or five notes that fitted over all the chords.

“A lot of it came down to our parents’ record collections. Jools’ parents and my parents had similar tastes. We’d come back from the pub, and Jools would start playing a Ray Charles tune – and I’d know the bridge ’cos my dad was a big Ray Charles fan too.”

The television work can be demanding, and Flanagan singles out Hootenanny, which has become a New Year’s Eve institution, as the most taxing of the shows he works on. “When we do Hootenanny, that is a bit of a marathon. We rehearse day one, on the Monday of the week we are recording the show, with just the band. Tuesday, we go to the studio, do a soundcheck, then they start running the cameras and we play the tunes with two or three of the guests.”

“Wednesday, we rehearse with the rest of the guests and then in the evening we record the show. The Tuesday Later shows are great because they’re live and have a lot of edginess. I’ve played for 27 years with Jools and had to play lots of different things, so I guess that’s why my style is quite diverse, because I try to play whatever is the right flavour for the tune. The one thing Jools doesn’t want us to do is imitate to the nth degree.”

Playing alongside some of the world’s most talented and famous musicians is all part of the job for Flanagan. “I’ve been fortunate to play alongside some memorable artists,” he says. “Amy Winehouse was so special – she did a radio show with us before Back To Black came out, and we had to learn Love Is A Losing Game in front of her, having never heard the track! We’ve played with Eric Clapton several times, he’s a fabulous guitarist and really nice guy. Mark Knopfler is another superb player I admire. He was setting up in the recording studio with us and he pulled this beautiful 1954 blonde Gibson Super 400 out of the case – prettiest thing I’ve ever seen. I said, ‘Wow man – that’s a pretty guitar’. Mark said, ‘You’ve got to play it to know it’ – and he handed it to me.

“The neck pickup was pure jazz guitar – just as you’d expect, warm and ‘Gibsony’; the middle pickup was like an acoustic, you could have got away with playing dance band stuff, even folky stuff. But the back pickup – oh! Turn it up a bit and suddenly it’s like T-Bone Walker and it’s screaming, so responsive, a great guitar.

“Jeff Beck was amazing. We did Drown In My Own Tears three times with him – once in the studio, again on Hootenanny, and also at the Albert Hall. When he was at the Albert Hall, he really took off man, I tell you, I nearly forgot to play because I was just mesmerised by what he was doing.”

Flanagan has been getting some use out of his dad’s old guitar, using it on the Rhythm and Blues Orchestra album Sirens Of Song.

“It’s a Wilson that was made in Australia with an Indonesian hardwood fingerboard. Martyn has done a beautiful job of rebuilding it, but it’s an F-hole cello guitar with flatwound strings, so no good for country twang! But it’s quite good for blues, as it has that old-fashioned 1930s sound to it. When you hit the chords, it sounds pretty dead, but my dad always said it’s a drum – a rhythm instrument and a dance band instrument.”

“Anyway, last year we did a few swing tracks for the album, one with Emeli Sandè called Love Me Or Leave Me – and the two or three tracks I used my dad’s guitar on; suddenly, it sounds like a big band. Even though it just goes ’thwack’ and doesn’t resonate too much, if you put a mic on it and get the levels right it disappears into the drum kit – somewhere between the snare and the hi-hat – so it becomes a sort of melodic snare drum.”

“You hear the changes, but you don’t really hear anything else. I was so pleased, and my dad would have been made up because it fitted right in with the ‘sonic’ of the whole thing with the horn section and everything else – it’s perfect.”

A Gibson ES-335 is Flanagan’s main live guitar these days, the fulfilment of a lifelong ambition: “It’s a 1967, and the finish on the front has been removed – it’s just the natural wood. I’d been playing my old Strat with Jools, but I’d wanted a 335 since I was a kid.

“I got the chance through a friend in London who used to work for The Rolling Stones. He had a 335 and very kindly lent it to me for a few months. I played a few gigs with Jools and realised it was a lovely guitar – and that I should probably buy it! So I’ve had it since 1990, but before that, I was a Strat man. I play it through a 1958 tweed Fender Twin.”

The ‘67 ES-335 has survived a few scrapes over the years, with one incident in particular almost leading to its untimely demise.

“I packed up my gear into the back of my estate car,” Flanagan remembers. “I left the 335 leaning against the side of the car, slammed the tailgate and drove off. I was about a mile out of Harrogate when I realised what I’d done. I drove back and there was the guitar – on the road in a soft case, soaking wet in the rain with a tyre mark over it!”

“I couldn’t even look – I just put the case in the back of the car and went home. When I plucked up the courage to look, just the edges of the volume and tone knobs had broken off, so a car must have just brushed it, rather than driven right over it. It’s had a charmed life – oh, and the headstock inlays have shrunk over the years and fallen out like damaged teeth!”

“I bought my Dobro from Macari’s on Charing Cross Road, having [previously] borrowed a 1930s one from a friend of a friend. I finally got around to the open tuning thing – and remembered what my dad had told me all those years before.”

“I was looking around Macari’s when I saw this silver one and started to play it, but the action had been set up too low.

“I thought it had potential, with a nice P-90 in the neck and an LR Baggs in the bridge. I decided to take a chance on it, it’s really open and has gorgeous tone. It’s great – I love that guitar.”

From those humble beginnings jamming with his dad, Flanagan has come a long way in music and is grateful that fate engineered the meeting between he and Holland that changed the trajectory of his musical career.

“Well, when I first started, I didn’t even think of it as a ‘career’,” he laughs. “But looking back over 40-odd years of playing, I can see that I’ve been very lucky. I’m lucky that I met some great players early on – and lucky to meet Jools. That was a real step up; and what we’ve done together over nearly three decades is pretty astonishing.”