Robbie Robertson on Bob Dylan, Chuck Berry, and the influence of Martin Scorsese

The Band’s leader, film score maestro and guitarist for Bob Dylan’s most controversial tour ever shares his memories of a fascinating career.

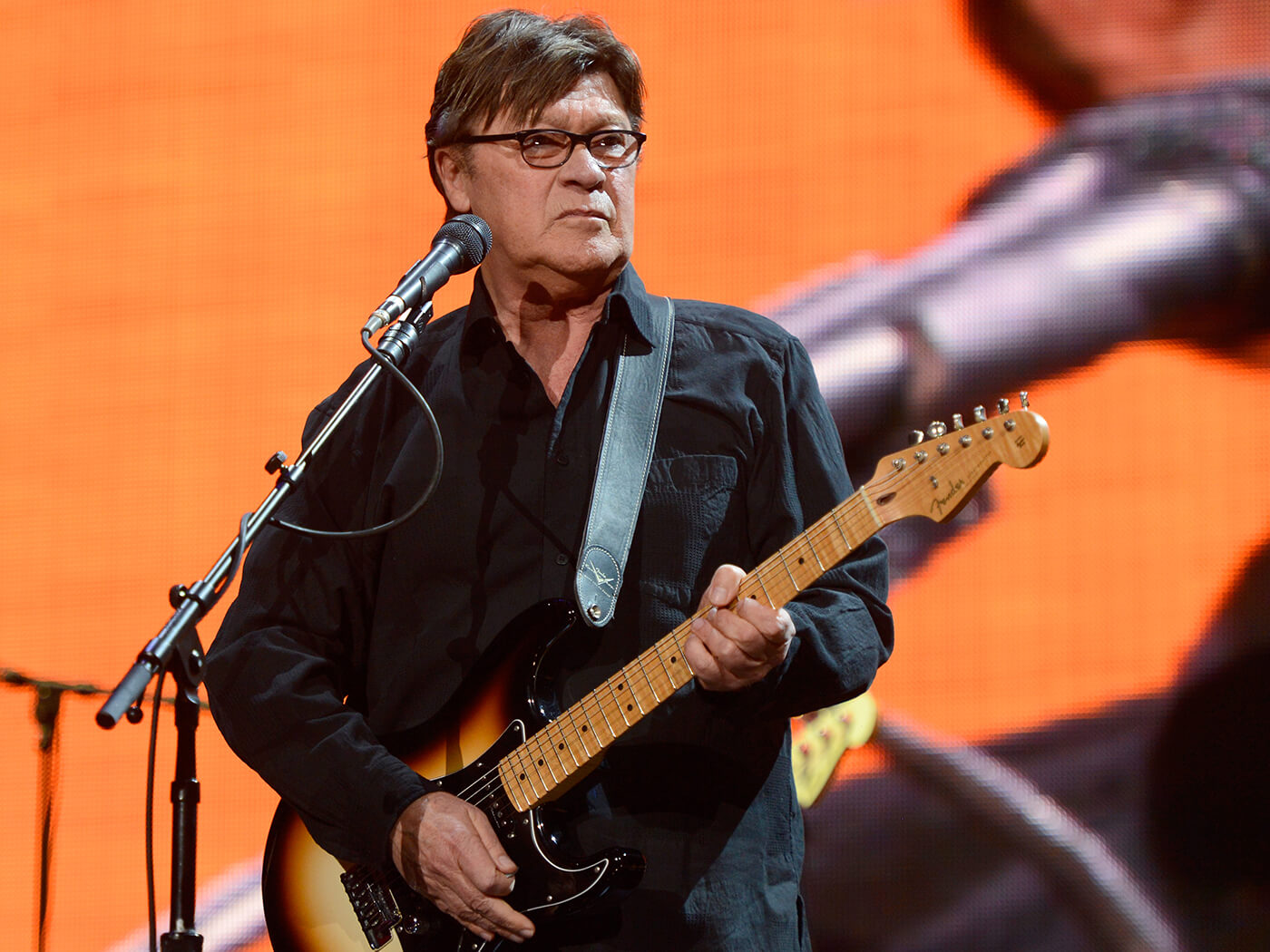

Robbie Robertson performs on stage during the 2013 Crossroads Guitar Festival at Madison Square Garden on 13 April 2013 in New York City. Credit: Kevin Mazur / WireImage

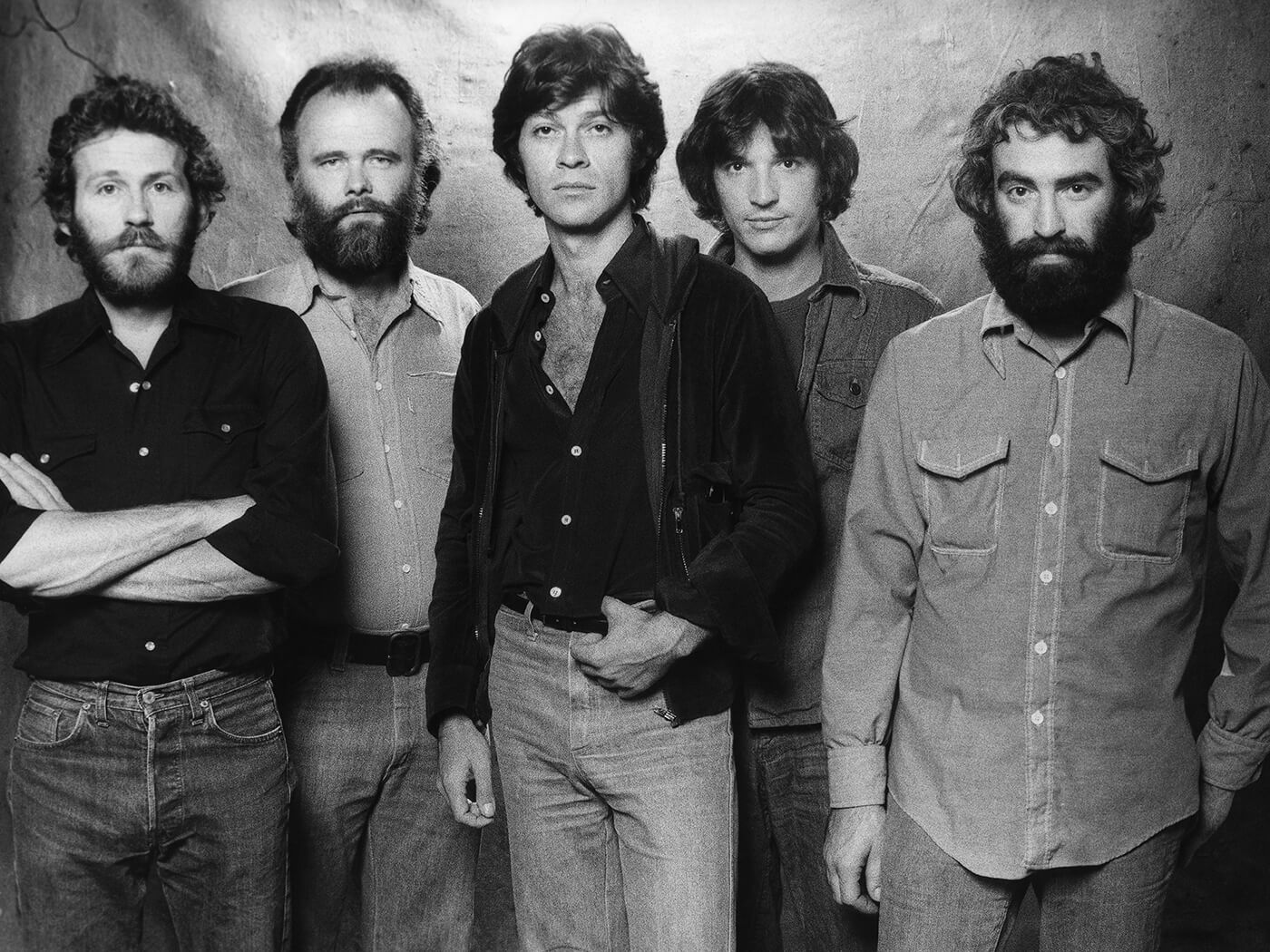

“We weren’t trying to be famous,” says Robbie Robertson of The Band, the Canadian-American outfit that he fronted between 1968 and 1977. But become famous they did – very much so – especially in the period from their debut album Music From Big Pink, until their initial breakup eight years later at the height of their popularity. Although their profile has wavered over the decade, The Band remain acknowledged by numerous players across generations as one of the great rootsy bands of all time.

“We just wanted to hone our own musical skills,” he continues. “To share something unique that was so musically deep from all the music we had gathered from playing the chitlin’ circuit in the American South that stuck with us.”

Robertson, born Jamie Royal Klegerman on 5 July 1943 in Toronto, Canada to a woman of Mohawk-Cayugan decent, was raised on an Indian reserve where he learned to play guitar from the village elders.

“Everyone there either played an instrument, or sang and danced, but there was always music going on,” Robertson remembers. “Even as a kid I thought, ‘I gotta figure out where I fit in here, to be part of this club’. So when I got old enough for my hand to reach around the neck of a guitar I talked my parents into buying me this big old acoustic guitar. After a while, I realised, ‘You know, I’m actually getting as good as these older guys,’ and people were saying, ‘Look at you. That’s really good!’ So, this kind of encouragement led me to think, this is something I should stay with.”

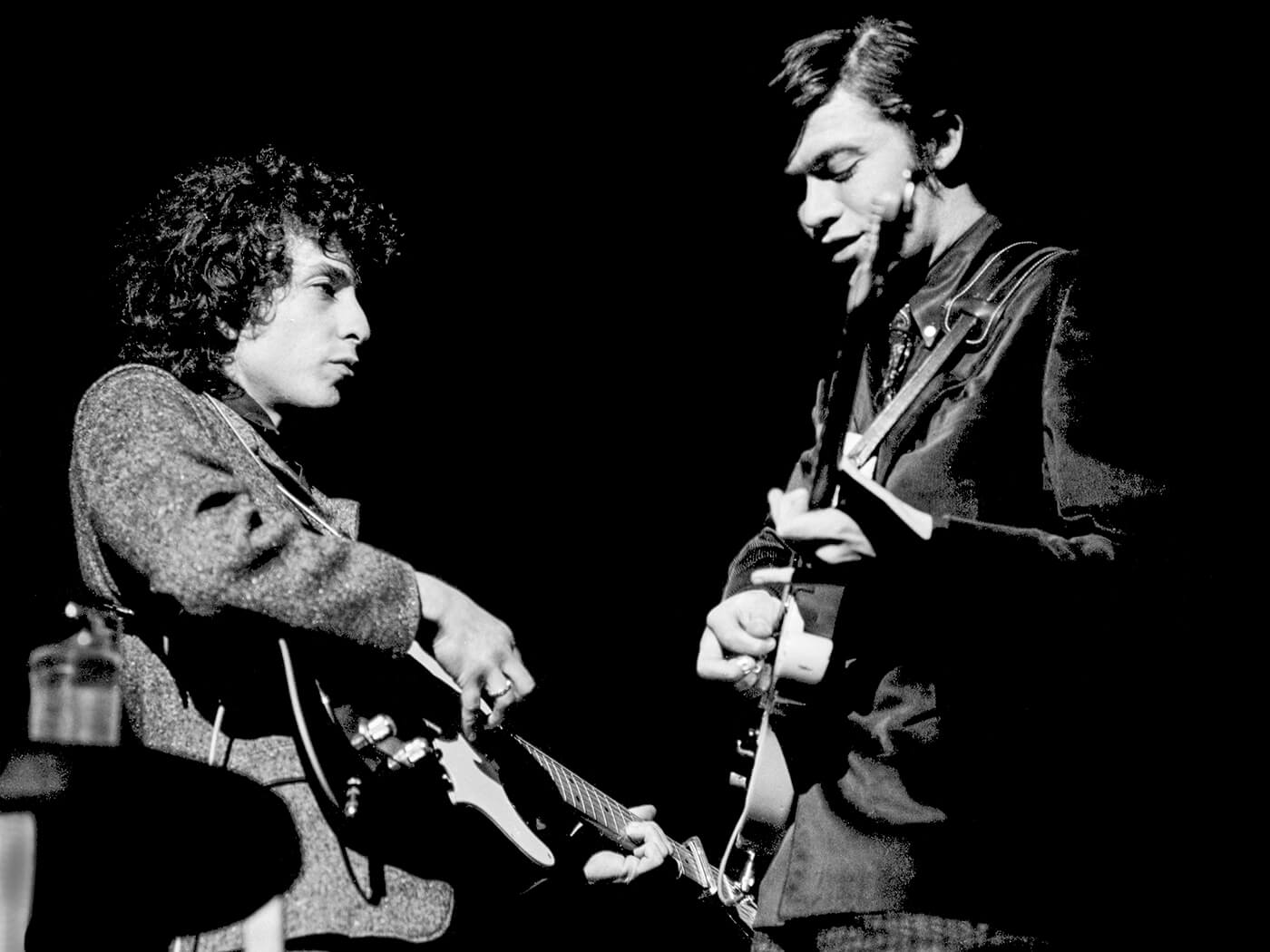

After meeting Canadian rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins in 1959 at the age of 16, Robertson became a member of his band, The Hawks. This was where he met future Band members, singing drummer Levon Helm, bassist Rick Danko, multi-instrumentalist Richard Manuel and keyboardist Garth Hudson. After parting ways with Hawkins in 1964, the five musicians were hired by Bob Dylan to be his touring backup band. Although Dylan was the biggest solo artist in America at the time, it ended up being a somewhat harrowing experience for all involved.

The Band would go on to be acknowledged as an influence by the likes of George Harrison, Elvis Costello, Elton John, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen and Robert Plant. None other than Eric Clapton even admitted that hearing The Band’s first album convinced him to leave Cream, and that he actually wanted to join Robertson and company at the time.

A true renaissance person as a musician, singer, songwriter, film scorer, record producer, author, actor and director, Robertson’s latest album, Sinematic, his first in eight years, continues his more than five decades of musical excellence…

Is there any particular significance for this album’s title?

“Yes, because all those songs seemed like little movies, and I was working on two different movie soundtracks while I was recording them. Reading screenplays has always been a big inspiration for my music, and from working with the great film director Martin Scorsese, I just thought, ‘I gotta face the truth here. This album should be called ‘Cinematic’ but spelled with an S.’”

The whole album has a dark, ominous tone to it…

Definitely. The opening song, I Hear You Paint Houses, was inspired by Scorsese’s newest film, The Irishman. It’s an expression used by big guys in the underworld who want somebody taken out. So, they go to a certain person who does this, and they say, ‘I hear you paint houses…’ which literally means, ‘Can you kill somebody for me?’ The expression refers to blood spattering everywhere. It’s not very sweet, but the music had to reflect the mood of the film.”

How did you happen to get Van Morrison to sing with you on the track?

“Van is a great friend, and whenever he comes into town we get together. So he came by the studio. I played him the song, and he immediately said, ’Man, I really like that. I want to sing on it,’ and we ended up doing it together.”

You use a lot of different gear on the album, what were your go-to instruments?

“Wow, that could be a very long answer! Because I use my own studio and have a lot of equipment to choose from. On the album, I used the Robbie Robertson Signature Moonburst Stratocaster with a maple neck and noiseless pickups as well as a second Robertson Signature that’s Capri blue with an amber see-through pickguard. It also has a maple neck with all brass hardware and Telecaster style knobs. I was also using a 1960 Gibson Les Paul Black Beauty, and a ’51 Martin D-28 acoustic.”

You also play bass on some of the tracks…

“Yes, for those I was using a couple of Fenders – a tobacco sunburst four-string American Elite Precision and a white Fender VI six-string with a tortoiseshell pickguard.”

What about amps and other gear?

“I used a Vox AC30 Hand Wired with a separate head in conjunction with a BC112 cabinet. Pedal-wise, I used an Electro-Harmonix Platform, and there’s a certain type of pedal I use called a BAE Royaltone. It’s a type of distortion pedal that has a very interesting characteristic about it. I also used a tap tremolo and a Line 6 delay. One of those pedals has a backwards thing that I like. I still use quite a few different tremolos and vibratos, something I’ve been drawn to since seeing Bo Diddley many years ago. I used a wah on quite a few tracks, but I think that’s basically kind of it in a nutshell.”

In your film documentary, Once We Were Brothers, you mention how the initial rock ’n’ roll explosion in 1956, when you were 13, was what inspired you to trade in your acoustic for an electric guitar…

“Oh, for sure. I knew that Elvis Presley played an acoustic guitar, but Scotty Moore played an electric…”

So in some ways you were like Keith Richards who was famously quoted as saying, “I knew I didn’t want to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty…”

“That’s true to some degree, but I also knew that Carl Perkins played an electric guitar. Buddy Holly played an electric guitar. I knew it was louder and smaller looking and cooler. So getting one became the mission I was going to go on. Even at that age, I had the idea that someday I’m going to go out in the world and write my own songs and do all that stuff. The idea of being 13 years old, reaching puberty, and I’m already standing at the crossroads. I was already good on the guitar. It was like a setup, that my destiny had already been written.”

Who were some of your other early rock ’n’ roll heroes?

“Well, Chuck Berry was the first guitar god, I guess, and did he have a sound! It wasn’t just his playing. It was a special sound out of his Gibson ES-350. In fact just recently, Gibson made me a one exactly like Chuck’s which had a very unique tonality, and I’d even talked with Chuck about this. In those early days, those hollow body electric guitars were a kind of hand-me-down from jazz in some ways from guys like Charlie Christian. Chuck told me when he started that all you could get was these semi-hollow body guitars. It wasn’t until later on that they had those little scrawny solidbody electrics.”

Bo Diddley, with his overdriven amp cranked up with the tremolo, was also a major influence…?

“Yes. I first saw him on an Alan Freed show when I was about 13, and it literally changed my whole outlook on life. That rhythm was the most wicked thing I’d ever heard in my life, and the way that he looked…this big guy with these horned-rimmed glasses (laughs) and just the way he was moving across the stage. Bo really opened the door for me to want to discover what was behind the legendary Chess label. It wasn’t acoustic blues like Robert Johnson. It was strictly electric blues, and when that door opened, it was exciting. That whole new sonic experience just went a whole other place for me.”

Did you ever get to see Howlin’ Wolf in person?

“Boy, did I! Wolf’s records, like Spoonful and Little Red Rooster went a whole lot deeper than any other artist I’d ever heard. When I went to a club where he was performing… oh, my God! As soon as he got onstage, I got a chill down my back that lasted literally every second he was performing. It was the most dangerous… the darkest, the dirtiest thing ever known to mankind, and I just loved it!”

When Wolf sang, ‘I’m evil as a man can be’, you really believed every word…

“Yep. There was this blue light shining down on him while he was singing, ‘I asked for water, and she gave me gasoline’. Holy shit!

Did you ever see Buddy Holly play in Canada?

“Yes. In 1957 he and The Crickets came to the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. I was so overwhelmed that after the show was over, I couldn’t move. I was just so slammed by the power of what he did. After the concert ended, he and the band were at the side of the stage packing up… there were no roadies in those days, and Buddy was putting his guitar in the case. I said, ‘Mr Holly, I’m just a young guitar player and I’m trying to get better, but I gotta ask you. How do you make those incredible guitar sounds?’ He just laughed and walked over to his amp, a Fender Twin, and said, ‘One day I blew a speaker, and just left it’.”

That’s an incredible story. So how did you at 16, meet this crazy guy named Ronnie Hawkins?

“At the time, I had this little group in Toronto, Robbie And The Robots and I was also was bouncing around with some other groups like Little Caesar And The Consuls that played mostly songs by Huey Smith and Fats Domino, New Orleans music. So we got booked to open a small arena that Ronnie was playing at. People were saying that he and his band, The Hawks, were the most bad-assed rockabilly band around. That they were wilder, faster, than Jerry Lee, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash… any of them! And we were the opening act.

“We went out and played and tried to be pretty good so hopefully we would impress Ronnie, but then as soon as he and the band came on, everybody had been right. It was the most raucous rock ’n’ roll I’d ever heard.”

And afterward, Ronnie invited you to move to Arkansas to try out for his band…

“Well, first of all what Ronnie didn’t realise was that at 16 I was too young to play in any of those bars! Also, I knew I still wasn’t good enough to play in this Southern rockabilly band. So I had a lot to overcome. I knew I had to outdo those other guitar players who had played with Ronnie, how to step up and make an explosion. I just kept picking up ideas and sounds and people taught me tricks. I worked so hard that Ronnie finally thought, ‘This kid’s on fire’, and I think I made him believe I was really going to turn into something, so he ended up hiring me.”

What kind of guitar were you using at the time?

“Very early on when Fred Carter Jr was still in the group, I was playing rhythm behind him with a Gibson 335. Then before he left, being from Louisiana and starting out on the famous Louisiana Hayride with all those great pickers, he told me, ‘The guitar you have to play is a Telecaster, and you have to use a banjo string for the first one, and move the others down’. I’d never heard of such a thing, plus it was much lighter and easier on your back and shoulder than a Gibson!”

When The Hawks backed Bob Dylan on his ’65/’66 world tour, he was ‘going electric’ which caused some abuse. What do you recall about the infamous Manchester concert when a fan called Dylan “Judas”?

“Well, it wasn’t tremendously different from many of the other concerts we were doing. I didn’t know of anybody in history that toured the world and got booed every single night. The Manchester show was the last of the British tour. All of these famous groups were there on the tour, The Beatles, Rolling Stones… and to be booed in front of all these great musicians really made me feel horrible, but I think it was one of the Beatles came over to us after the show and said, ‘Don’t pay any attention to them. The music is really good. Just keep playing your music’, and their attitude was really helpful.”

What special memories do you have of your years with The Band?

“The Band was an extraordinary brotherhood. From the time we started doing our own music for our first album, Music From Big Pink, we were able to go into this sanctuary, this little pink house in Woodstock, and invent something special. We were calling upon all our influences, all the sounds we’d heard and bring that forth in these songs, this musicality that was our truth. It was a sound that had incredible influence on music and still does to this day. For that I’m very, very grateful.”

You and Garth, of course, are the only two surviving members of The Band. How do you account for surviving the craziness of the music business, and still being productive and doing great things?

“I can’t speak for Garth, but on my end, curiosity is the key. I have so many things that I still want to accomplish and experience. I still have the same hunger for discovery, and feel I’m on the same mission as I was when I was 16.”

Sinematic by Robbie Roberston is out now on Macrobiotic/Universal.