Related Tags

Fuzz Was The Future: Distortion was destiny

Our journey through the unlikely birth of the first fuzz pedal continues, as Josh Scott takes us on a quest to recreate an accident.

As the world’s first guitar pedal, the Fuzz-Tone would set the template for every pedal that came after it

So, for those of you who have been following the past few articles, we dove deep into the situation and circumstance that led to what I believe is the greatest accident in guitar history – heck, maybe all of history.

Although much of what we love about guitar can be attributed to accidental discovery and the evolution of technology and ideas, this one feels different. When you evaluate the sheer number of coincidences that had to take place in a small 1960 recording session to make it happen, you’ll agree that calling it an ‘accident’ doesn’t really do it justice. ‘Destiny’ might be closer to the mark. That said, let’s pick up where we left off.

“Leave it in”

Country superstar Marty Robbins and his studio band have just wrapped up what should have been a very simple recording for the song Don’t Worry. But as they gather around the recording console and listen to the playback, they hear something weird. Not just weird, but wrong. It’s the kind of sound a recording engineer from the 50s would have dismissed as a technical malfunction. Recording music had rules, and rule number one was that a professional recording needed to be clean and clear. Many recording studios treated their profession in an almost clinical manner. Technicians at Abbey Road Studios in London even wore white lab coats and did not allow technically untrained musicians to touch the equipment.

It was almost a case of science over sound, and if you’ve learned anything through this journey into guitar’s rich technical history, then you know that ain’t rock ’n’ roll.

But recording engineer Glenn Snoddy and producer Don Law made a radical decision that day, one that would inevitably change the trajectory of where popular music in the decade of the 196’s was going. They heard what was, by all definitions, a disastrous technical malfunction in the recording process of Grady Martin’s guitar solo and said, “Let’s leave it in.” This choice broke every rule in the book; it was as gutsy as it gets. Before this moment, we’d seen small glimmers of distortion via overdriving valve amplifiers or busted speakers on tracks like Rocket 88, Rumble and How Many More Years, but this was different. This was a leap of sonic evolution. Distorted guitar wasn’t kosher on the airwaves yet, so they ran the risk of radio audiences thinking they’d accidentally released a messed-up recording – or worse, that the engineers had heard the mistake but were too lazy to fix it. This was the musical equivalent of putting all your chips on the table with nothing but a pair of face cards in your hand, but it paid off.

Soon after its release on 6 February 1961, Don’t Worry skyrocketed to the top of the charts, and peaked at number one on the Billboard Country Hits and number three on the Billboard Hot 100 within a month. Airwaves across the United States played this song in heavy rotation, sneakily exposing listeners to the new sound of fuzz, over and over, station after station. It was the perfect way to introduce such a questionable new approach to how a guitar could sound. Marty’s smooth vocal, the gentle piano, and the beautiful melodies kept you safe, and distracted you from just how out of the ordinary Grady Martin’s solo was. Up until this moment every distorted guitar in popular music had pushed the boundaries a little bit farther than before, giving guitarists a bit more permission to experiment, but Martin’s fuzzed out solo told guitarists and producers they no longer needed permission at all. This simple song by an unassuming country crooner, recorded in a metal shed in the backyard of a Nashville home, changed the sonic structure of guitar forever.

For guitarists, producers and engineers everywhere, this produced a wave of military-grade FOMO, the agony of hearing a sound but not being able to have it for yourself. It was the equivalent of some up-and-coming playwright hearing Shakespeare’s dope-as-crap use of iambic pentameter but not being able to try this style of poetry out for themselves.

Audiences and musicians alike loved the new “fuzz tone” sound, even if Martin himself wasn’t as big a fan, at least initially. Grady ended up building a whole song around the effect (The Fuzz, recorded with the Slewfoot Five and released in 1961) – like all good session pros, Grady Martin could see the way the wind was blowing and tacked his sail accordingly.

If it’s broke, don’t fix it

Not long after the Billboard success of Don’t Worry, Owen and Harold Bradley, the owners of the Quonset Hut studio where the song was recorded got a call from Nancy Sinatra. The pop superstar promptly booked an appointment to record at the Quonset Hut assuming that she’d be able to utilize the same ‘fuzz’ effect that was on the Marty Robbins recording – but there was one big problem. The broken recording console that had created the effect was, well, broken! And no self-respecting studio owner of the time would keep using broken equipment, so the console was replaced.

“[Nancy] didn’t like that at all,” Snoddy recalled. “They came there to hear that sound. It was something we had no control over, because it happened in the console. So of course everybody was disappointed in that. I told Harold Bradley that I’d have to see if I could make one and get it going.”

I’ve often said there are two types of people in this world: people who talk about doing things, and people who actually do them. Glenn took this opportunity, developed an idea around it and did what it took to make it a reality. He took the sound of that broken channel inside the Quonset Huts recording console and transported it into an approachable product for guitarists worldwide – the Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-1.

But like any true hero, he didn’t do it alone. Glenn brought in a local radio engineer named Revis Hobbs, and these two dudes (let’s call them the Captain America and Iron Man of their day) joined forces to develop the first ever manufactured guitar pedal in history. Don’t let the weight of this reality pass you by, because without this moment, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing this column, and my guess is you would probably be a trumpet player. Scary stuff.

Glenn + Revis

We’ve talked a bit about Glenn Snoddy so far, but not much about his less well known partner and co-inventor Revis Hobbs – let’s put that right. Unlike Glenn, Revis was a quiet and understated man. He never wanted attention. As far as Revis was concerned, he had played the perfect role in the invention of the FZ-1: he got to co-invent a groundbreaking piece of technology while avoiding the spotlight. While Glenn was an idea guy, a true salesman and a fantastic communicator, Revis was the silent genius type. You have to understand this dynamic to understand the story at hand; the lack of clarity here is the reason this story has been misrepresented for more than half a century.

In all my research on the FZ-1, I only found first-hand stories from Glenn. In reading these interviews, you see Glenn take full credit for “inventing” the Fuzz-Tone with no mention of Revis.

Now, Glenn didn’t maliciously exclude his friend from the story. The problem is that “inventing” can mean different things to different people, and in Glenn’s case, he had rightfully claimed credit for inventing the idea, just not the actual circuit. Revis was the technical brains and, in reality, the reason that the first guitar pedal ended up as more than just an idea. Because Revis never wanted to be interviewed or even to be seen for his work here, his side of this story has been all but lost. Like a true technician, as soon as he and Glenn had finished their work on the Fuzz-Tone, he’d already moved on to the next project. For him, the design was just a problem to be solved, not a trophy to display.

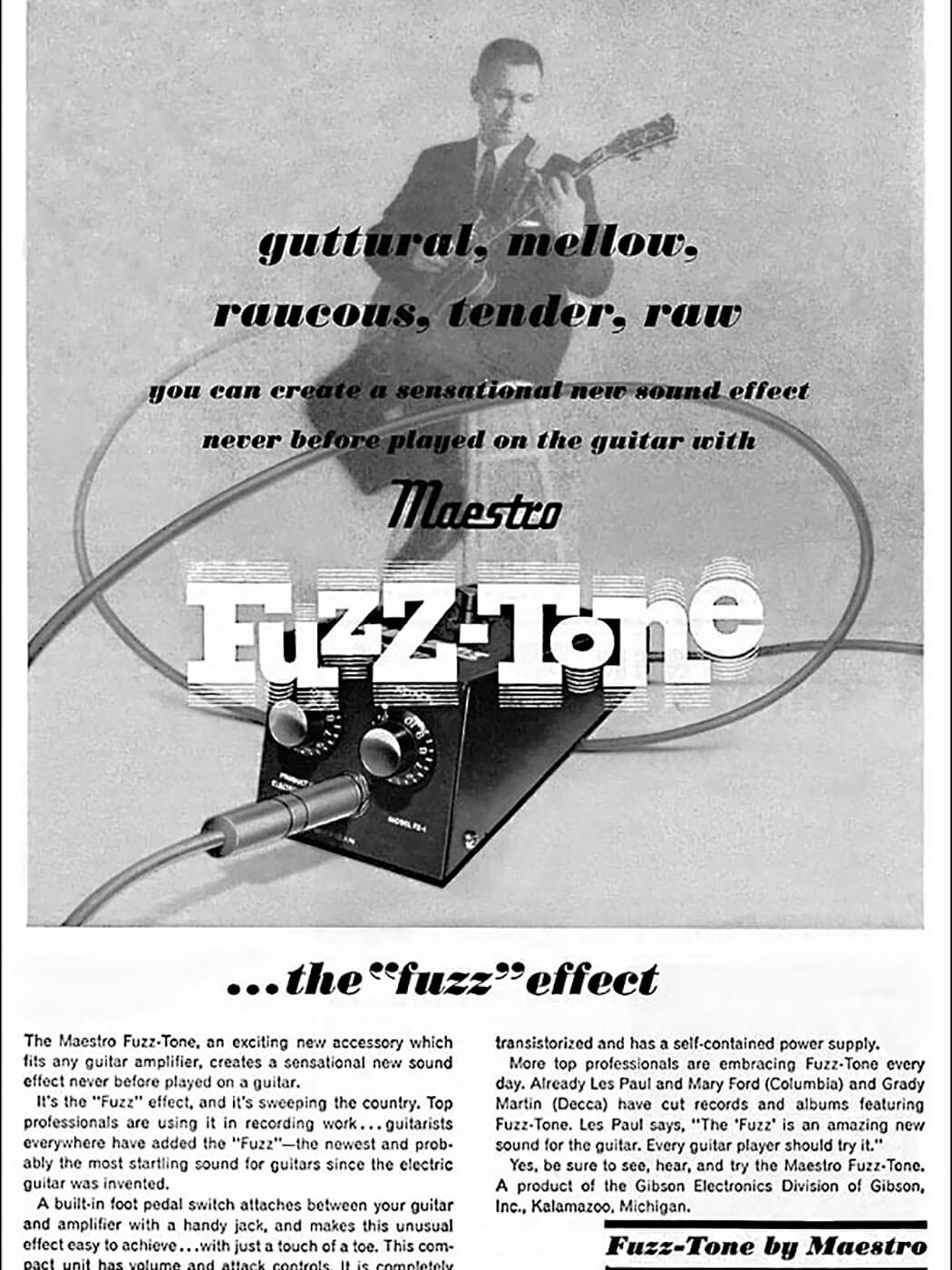

Nothing like this had ever existed before, and early advertisements rightly declared it to be the first self-contained guitar pedal effect

Ironically, Revis’s humility is what almost left him outside the guitar pedal hall of fame. If you compared Revis with a guitar hero like Les Paul, it’s almost funny: Les would take credit for anything and everything (whether he actually did it or not), and so he’s remembered as a genius. On the other hand, Revis – who most certainly was a genius – didn’t toot his own horn, so he’s forgotten. I don’t like that. If ever a man’s flag deserved to be hoisted up and flown next to the greats like Gary Hurst, Keith Barr, Roger Mayer, Bob Mayer and others who reshaped guitar’s very existence with the circuits that they made, Revis Hobbs is that man.

Revis was uniquely qualified to help develop the Fuzz-Tone pedal, as he’d been a technician with WSM Radio for more than five years and was the kind of guy who liked to read up on tubes and transistors in his free time. He wasn’t musical himself, but he was a genius with electronics. See, he’s basically Iron Man without the suit, right?

WSM, an AM radio station based out of Nashville, had a morning music show called The Waking Crew which was fronted by Owen Bradley’s band. Tommy Sparkman and Glenn Snoddy were the sound engineers, and Revis knew them from that association. Robert Hobbs, Revis’s son, often tagged along with his Dad to the Quonset Hut, and he remembered vividly how it all went down: “Dad got a call from Glenn, and he said, ‘Revis, we’ve recorded a song for Marty Robbins, and it had an unusual sound in it. And it has been on the charts for several weeks now at number one. And everybody feels like the sound has caused the song, the record, to go to the top of the charts. And I think if we could recreate that sound, that we might be able to make some money.’” Like any true hero, Revis answered the call. Literally.

Reinventing an accident

Glenn had already gambled on the success of keeping the fuzz sound in Don’t Worry and it worked, so it probably wasn’t difficult to convince Revis to jump in for this next business venture. Robert (Revis’s son) remembers getting in the car with his dad and driving to the Quonset Studio. Glenn played back the original recording for Revis. He recalled that Grady Martin was actually there recording a session when they arrived, so the whole place was already “packed full of equipment, and people smoking and a session going on.”

At first, they started working on the basic circuit design in the basement workshop of the Bradleys’ home, just a few feet from the studio where the accident had occurred. Revis was the kind of guy who dreamed of circuits, components and the technical aspects of sound; he had been accidentally preparing for this moment for years. Robert remembers his dad receiving transistor data sheets in the mail and carefully adding them into a binder of RCA transistor specs; if this doesn’t scream super nerd, I don’t know what does.

Revis would drive down to Electra Distributing Company on West End in Nashville and buy the parts that he thought he might be able to use on the design. Just the transistors and basic components, though, because Revis and Glenn still didn’t know exactly what the finished product would look like or what the enclosure would be.

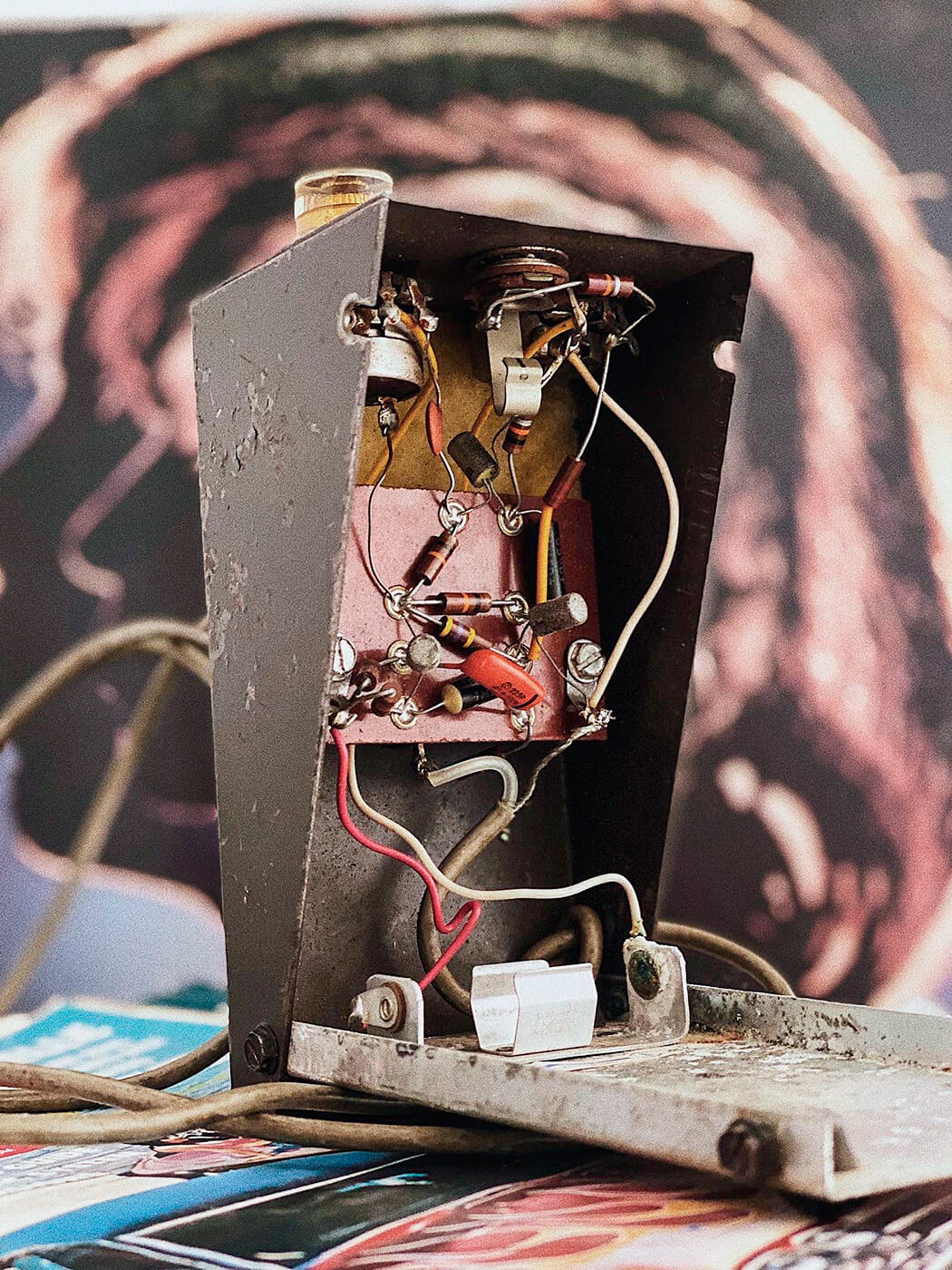

Over the next eight months, Revis and Glenn hammered out the prototype, working just as often at Revis’s workshop as they did at Glenn’s. When all was said and done, Revis would finish the world’s first three-transistor fuzz circuit and, even more importantly, the world’s first guitar pedal: the 1962 Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-1.

Glenn, the salesman and outgoing guy that he was, would personally drive the prototype to Maestro headquarters in Chicago to make his pitch, and the rest is history.

The Maestro Fuzz Tone received an official US patent number 3,213,181 and found itself beautifully adorned in a brown wedge-shaped metal enclosure, two control knobs, a cable attached to its side and a classic mid-century typeset that read ‘Maestro’ across its face. It was a giant step forward from the remote footswitches that activated the onboard tremolo or reverb of amplifiers of the time. Nothing like this had ever existed before, and early advertisements rightly declared it to be the first truly self-contained pedal effect unit for guitar. Just as early 1950s rock ’n’ roll had set the stage for the coming rock invasion of the 60s, the FZ-1 was the forerunner to what was to come in the world of guitar effects. You could say that it was the first drop of rain in the coming flood of guitar effects that would arise over the next several years

With a device this revolutionary, you would think that selling it would be easy, but history tells a different story. Gibson had made a product that they didn’t know how to sell for people who didn’t know how to use it, which – shockingly – resulted in disaster. But, in the typical fashion of this story, fate decided to intervene one last time.

Three years after its release, right as this failed product’s funeral dirge was about to take place, a young guitarist named Keith Richards and his band called the Rolling Stones had an accident of their own that would turn the page of guitar providence one more time.

Next month we will wrap up this epic four-part story with the last chapter of the Fuzz-Tone’s unlikely road to success.

Join Josh for more effects adventures at thejhsshow.com.