Primal Scream, Screamadelica and me: “He was frantically painting Tipp-Ex dots on the fretboard so he could find the notes”

Back in the 90s, Guitar Magazine’s DIY and recording expert Huw Price was an engineer at the studio in London where Primal Scream recorded their masterpiece, Screamadelica. To mark the 30th birthday, here Huw shares his memories of those remarkable sessions.

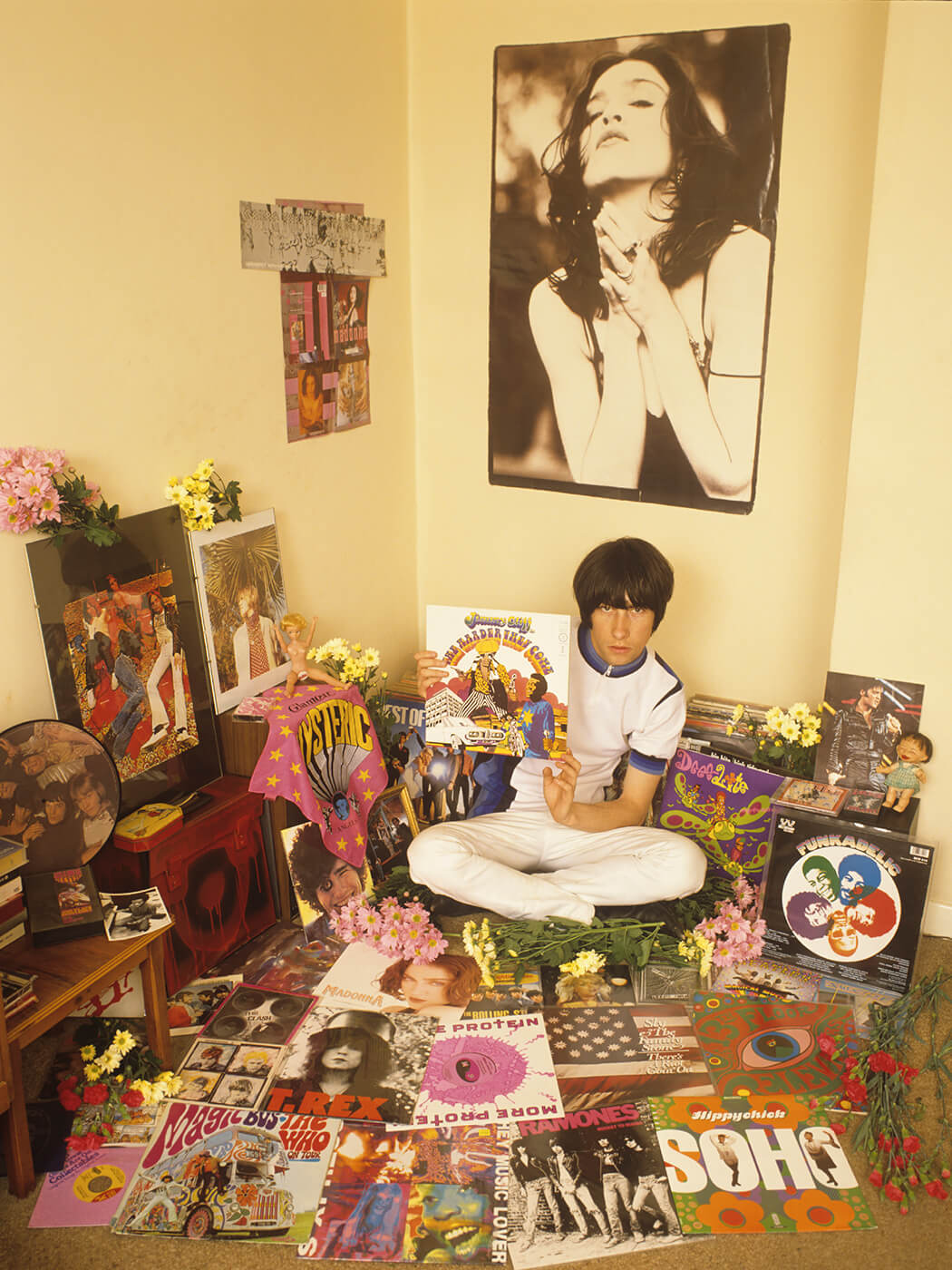

Primal Scream. Image: Tim Roney / Getty Images

When Primal Scream came together to record Screamadelica in 1990, there was a real sense that something special was happening. I remember it well, because I was there to witness and assist in the creation of one of one of the defining albums of the decade.

Back then I was working at Jam Studio in London’s Tollington Park. Previously named Decca 4. Jam was an old school studio featuring an orchestral live room and a glorious collection of vintage microphones and outboard gear – it was certainly more 1970s than 1990s. Like other studios from its era, Jam even had a flashing blue light in the control room that could be activated up in reception if the police showed up! But Primal Scream had recorded the standalone single Come Together (which would be heavily reworked by Andrew Weatherall for the album) at Jam, so they were happy to grab the studio time that Creation had previously booked for My Bloody Valentine, a band with which I had previously also worked.

A rocky start

My time working on Screamadelica didn’t get off to the most auspicious start, I was off sick for the first two sessions, and in the third I almost immediately had an altercation with Primal Scream’s engineer, followed by another a few days later. The following day, however, we received news that the engineer in question wouldn’t be returning, and that myself and my Jam colleague Paul Doyle would be taking over the sound engineering duties ourselves with our tape op James Gillespie (no relation) assisting.

We set about our task with enthusiasm, and our main microphones were a valve Neumann U47 and various Neumann U67s and AKG C28s. We recorded onto Ampex 456 two-inch tape using a Studer 24-track. Whenever possible I bypassed Jam’s Harrison desk and recorded directly to tape via Summit and Drawmer 1960 mic amps, with UREI 1176 and DBX 165 compressors.

Kick out the jam

I found Bobby Gillespie charismatic, likeable and fizzing with energy. He dressed like a rockstar and was unafraid to behave like one. He was also insecure about his vocal abilities and said he would be more than happy for the band to bring in another lead singer. This was shortly before Denise Johnson joined the group.

One evening James and I stayed late for Bobby to lay down a lead vocal. Although he was doing fine, he became increasingly frustrated with himself. Rather than take it out on the studio staff – as some singers are prone to do – Bobby was extremely apologetic and concerned that he was wasting our time. We both tried reassuring him that he wasn’t wasting our time or his. I liked his voice, and I still do – because nobody sounds like Bobby Gillespie.

Robert Young (aka Throb) had a formidable physical presence. Like a long haired, guitar-slinging Sean Connery, he seemed rock ’n’ roll incarnate. One evening we were chatting about Tim Buckley and I mentioned I couldn’t find his first album anywhere. When Robert got home, he made me a cassette from his vinyl copy – complete with a song list done in his own elegant handwriting. I still treasure it, and I remember him fondly.

From a musical perspective, Andrew Innes was a key driving force. As well as being an excellent rhythm guitarist, he had assumed programming duties and spent most of the Screamadelica sessions in the rear corner of the control room with his Atari 1040 computer and AKAI sampler.

I remember him being focussed and hardworking, but always ready to respond with a curt “not my department”, when asked to cover any of his bandmate’s duties. The vast majority of his programming contributions didn’t make it to the final mixes, but I doubt he ever intended them to.

When you hear the heavily compressed acoustic guitar on Movin’ On Up, that’s all Innes. The guitar in question was a vintage Gibson J-45, courtesy of Harris Hire, and it was one of the few things recorded – splendidly in my view – by the band’s original engineer.

Keep the faith

George Michael’s Faith was a big inspiration for the track and the Primals were keen to achieve a Bo Diddly groove without resorting to conventional drums. Based on his work with The Rolling Stones, Jimmy Miller was the obvious choice to mix the track and he did an amazing job.

Paul and I worked together during daytime and took it in turns to cover the evenings. Sessions rarely ran late because some of The Primals lived on the South Coast and they travelled home each night. One morning James told me Robert had used my 1963 Strat to record the lead guitar parts the previous evening. Whenever I hear Movin’ On Up, I still get a buzz from that.

Primal Scream appeared to comprise two distinct camps: the Scottish contingent, and everyone else. Drummer Philip ‘Toby’ Toman and bassist Henry Olsen had played together in former Velvet Underground singer Nico’s band. Throughout the Jam Studio sessions, Toby wasn’t called on to do much. I recall him playing on Damaged and recording some percussion, but the intention was to leave drums and grooves to the mixers.

I found Toby friendly and easy going, and it was good to run into him at a London venue a decade later. He expressed relief at having left Primal Scream when he did and looked in good shape.

In a band that appeared to be living out a collective Rolling Stones fantasy, bassist Henry Olsen’s gentlemanly demeanour, understated musical prowess and gentle courtesy made him The Primals’ Charlie Watts. Henry had studied orchestration and composition, and graduated from Salford University.

He joined the band after Robert switched from bass to guitar, and in addition to some amazing basslines, he contributed vocal harmonies, vibes and double bass. Over the following years we would occasionally run into each other and eventually became very good friends.

Henry now improvises free music on unconventional acoustic guitars of his own devising, and has even recorded at my house because he likes the natural reverberation in the hallway. He now practices as a music therapist and has just released a solo album called Dock Street.

As I recall, Martin Duffy hadn’t officially joined The Primals when they recorded Screamadelica – but that was merely a formality. He had a mischievous sense of humour, revelled in ‘Zen jokes’ was often the worse for wear.

I got the impression that certain members were conducting a prolonged experiment to determine how wasted he would have to be before he could no longer play. But whenever he sat at Jam’s Yamaha grand piano, Duffy played like an angel.

Coming together

With mixing and recording being done simultaneously, Henry and I drove over to Eden Studios one evening to check how a Come Together mix was progressing. On another occasion, a courier delivered The Orb’s mix of Higher Than The Sun to Jam.

The band convened in the control room and with the lights dimmed, I played the DAT copy through Jam’s big monitor speakers. Being present when Primal Scream heard Higher Than The Sun for the first time, I recall a sense of awestruck euphoria in the studio.

Before the early 1990s, traditional guitar bands and electronic dance music existed in parallel universes. Some indie groups were getting their tracks remixed, but crossover remained limited. The Primals had embraced acid house culture and all it entailed, and devised a strategy to progress beyond their status as paisley-shirted indie also-rans.

The process that began with their breakthrough single Loaded continued throughout Screamadelica. The band would record a song to near completion, then the multi-track tapes were surrendered to DJs and remixers who had licence to do as they pleased.

The band members didn’t attend the mix sessions and the mixers were not present during recording – but they justifiably received producer credits. The salient point is that the remixes are the only mixes on Screamadelica.

Although the band selected the mixes they preferred, it was a bold move. A lot of guitar, vocal and sequenced parts were discarded and never heard again. The band’s Screamadelica recordings sound very different to the Screamadelica we all know and would never have broken musical barriers in the same way. That said, there are rumours that the band’s versions are slated for release with the working title Demodelica.

Doing damaged

In contrast, Damaged is the only Screamadelica track that was performed live. It was released almost exactly as we recorded it and Jimmy Miller’s mix has a commendably light touch. For me, recording Damaged live was the most exciting Screamadelica session and demonstrated how well The Primals functioned as a band.

Innes played the J-45 acoustic, Toby played a snare drum and cymbals and Duffy was on piano. Bobby sang a guide vocal and Henry grappled with a rented double bass.

Everybody was feeling pretty energised but Henry was fiddling about with something and keeping everybody waiting. I tried chivvying him over the talkback, with perhaps a little more force than I had intended. I remember Innes laughing and saying “woah Shuggie”.

It was the first time I’d heard the Scottish variation of my name, but I liked it and I’ve always used it on guitar forums. Years later, Henry told me he had been frantically painting Tipp-Ex dots on the fretboard so he could find the notes.

The basic track was done in a handful of takes. Duffy overdubbed some Hammond organ and Robert added some guitar solos using a vintage Les Paul Junior through a cranked Vox AC30. It was an attempt to replicate Mick Taylor’s tone on Winter by The Stones, but it was later deemed too overdriven.

Paul Doyle subsequently re-recorded the solos with a 1966 Telecaster through a cleanish 1972 Fender Deluxe Reverb. Henry suggests Jimmy Miller comped the solo together from parts played by himself and Innes. I still have a rough mix with Robert’s solos and I like both versions, but I think the band chose wisely.

Movin’ on

Screamadelica was one of relatively few albums I’ve recorded that felt potentially important as it was being made. There was an air of anticipation around the band – as if they already sensed that Screamadelica was about to change their lives. In fact, would change many people’s lives.

Creation failed to credit Paul, James and myself so the album didn’t change much for us – professionally at least. Shortly after The Primals sessions, Jam’s bank pulled the plug and we were all out of work. I got the news on the morning I was due to begin a Penguin Café Orchestra album.

I lost touch with James, but Paul and I continued as freelance engineers. We helped each other out whenever possible and occasionally worked together, but he eventually returned to Ireland.

The Georgian villa that housed Jam Studios was converted into flats – a fate that befell other great London studios during that era. It was the last full-time sound engineering job I ever had and in all my years of freelancing I’ve never found another studio I liked as much. Jam was a lesser known but historically significant British recording studio and Screamadelica couldn’t have been a better swansong.

For more features, click here.