Related Tags

The Genius of… Real Life by Magazine

The British band’s debut album might very well have put the ‘post’ in ‘post-punk’ but that really depends who you’re asking…

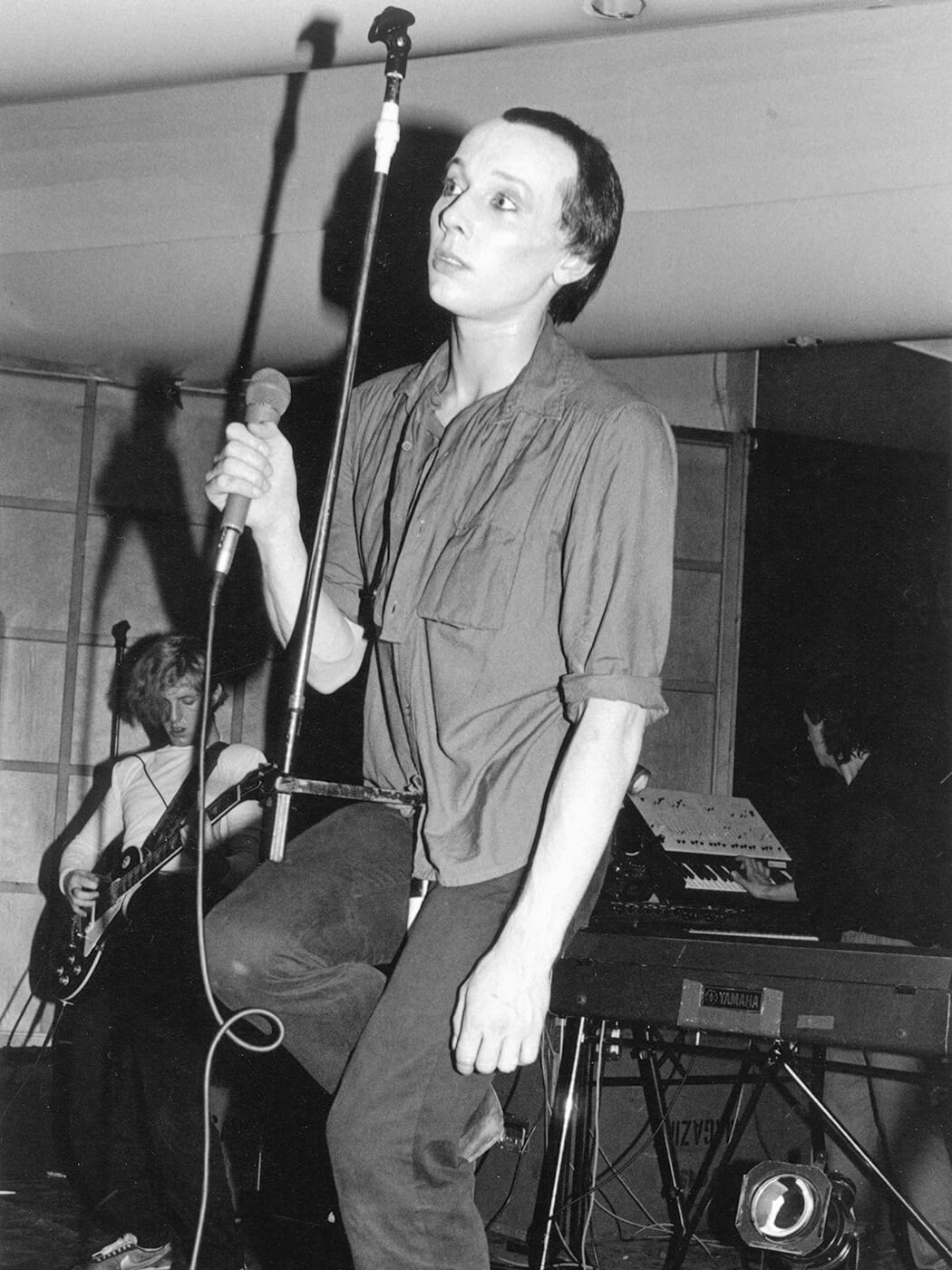

Image: Ebet Roberts/Getty Images

Who would have thought that four letters and a hyphen could cause this much consternation? Folks have been affixing post- to punk or rock or pop for more than 40 years, and yet it remains a prickly practice. There have been times, though, when it was essentially the only logical step available. Being confronted with Magazine’s Real Life in the summer of 1978 feels like it was one of them. This was a record that came from punk, but it wasn’t punk. It sounded like the future. It sounded post-.

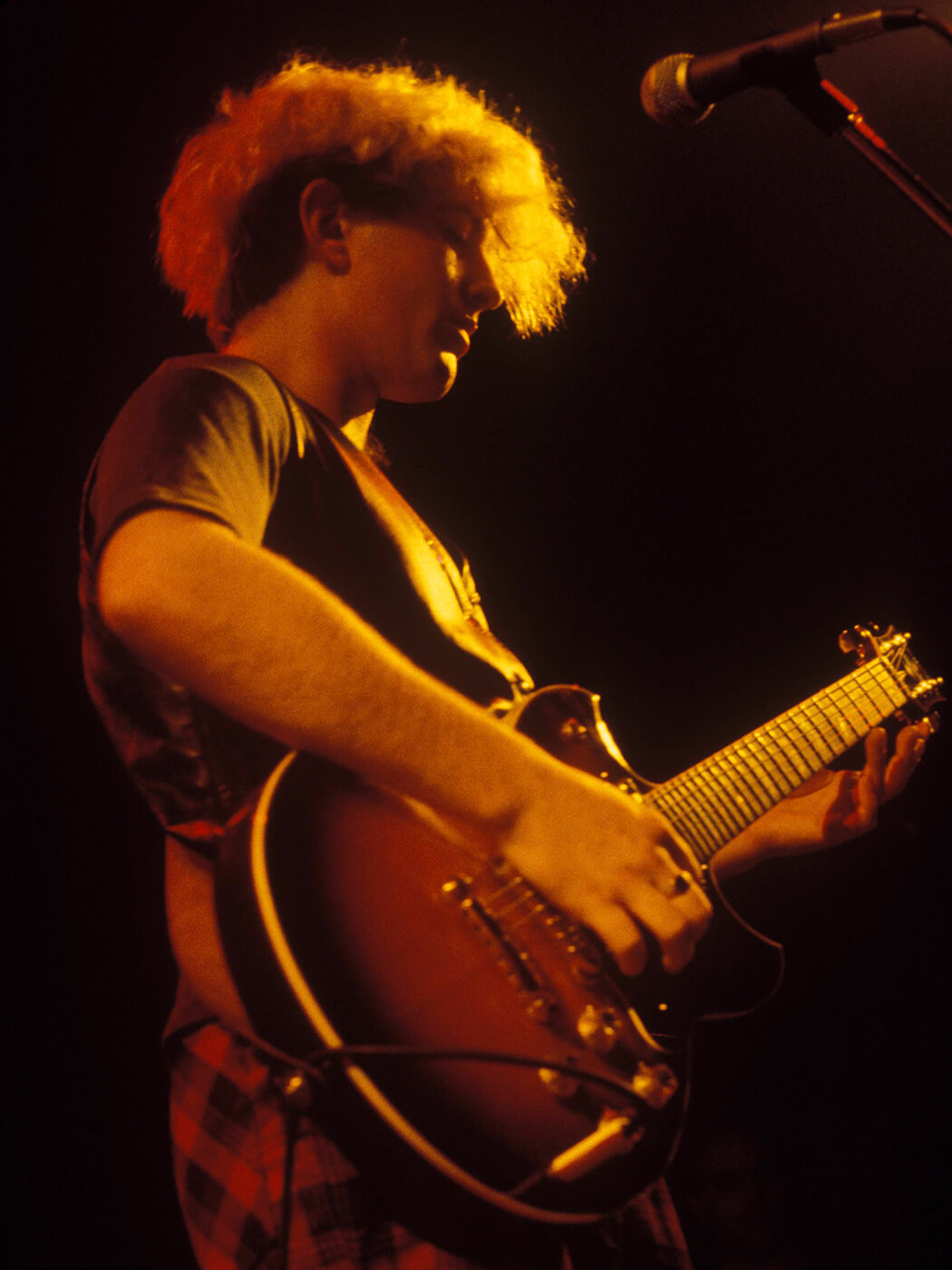

One of the key reasons for that delineation was John McGeoch’s guitar playing, which was lithe, helplessly melodic and only occasionally in thrall to the slashing power chords that had carved a path through the rock landscape in preceding years. Most of the time, he seemed to be in a lively conversation with Dave Formula’s grandiose keys. Siouxsie Sioux, who would call on McGeoch’s talents with the Banshees for several influential years following his exit from Magazine, once said: “I loved the fact that I could say, ‘I want this to sound like a horse falling off a cliff,’ and he would know exactly what I meant.”

Seeing the light

After leaving Buzzcocks in 1977, shortly after serving up Spiral Scratch, an insistent early punk masterpiece, vocalist Howard Devoto cast about for a fresh start. “I don’t like movements,” he said. “What was once unhealthily fresh is now clean old hat.” In The Light Pours Out of Me, Rory Sullivan-Burke’s excellent biography of McGeoch, he recalls learning through a friend of a Scottish arts student guitarist who could play Television’s Marquee Moon back to front. “That made me think he would be somebody worth knowing,” he said.

And wouldn’t you know it, he was right. Initially armed only with a couple of songs co-written with Pete Shelley and held over from his time with Buzzcocks — including their seminal first single Shot From Both Sides — Magazine set about pushing at the boundaries of what a rock band schooled in punk might achieve. McGeoch attached his outsized musicality to a sense of minimalism, playing complex, spiraling lead lines and solos that were always seamlessly integrated into the whole. With Devoto’s lyrical disaffection sitting like a weight at the heart of the record, Real Life was beautiful but self-contained, a butterfly in a jam jar.

Adapt and overcome

McGeoch was born in Greenock, Renfrewshire in 1955, and moved to Essex in his teens with a Commodore (an Aria 1532T sold under a different name) bought second hand for £25.00 with his paper round money in tow. Eventually, he settled in Manchester for university, where he orbited but never fully joined a burgeoning punk scene that seemed to radiate out from the Sex Pistols’ show at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in June 1976, which was organised by Devoto and Shelley (in attendance: Morrissey, Mark E. Smith, members of Joy Division, and Mick Hucknall, but probably no-one else who’s ever said they were there).

When Magazine began playing shows, haphazardly at first but quickly hitting their stride, the Commodore was still in McGeoch’s hands. But once they received an advance from Virgin, he put down a deposit on a Yamaha SG-1000 at A1 guitars and, as Devoto observed in The Light Pours Out of Me, set about adapting his MXR flanger, the cornerstone of his sound, so that it could be utilised by hand from a mic stand. “John’s playing was a deliberate modernism,” Johnny Marr told the Guardian in 2022. “The flanger modulates the signal so that it wobbles, and the effect is psychedelic. Not ‘oh so trippy 60s man’ or Hendrix, but psychedelic like you’ve taken bad acid or been psychotic after three days of speed.”

Mobile home

Having quickly moved from Shot From Both Sides to embryonic versions of Real Life cuts such as the towering The Light Pours Out of Me, and with Formula taking over from Bob Dickinson on keys, Magazine set about assembling an album that delivered on the buzz created by their debut single which, despite topping out at number 41 on the charts, had been well-received by the press. John Leckie, who had produced their Touch and Go single and established a rep for this sort of thing by working with XTC and the Adverts, returned to the fray, pulling 12-14 hour days and utilising a 24 track Virgin mobile studio at Ridge Farm near Guildford before finishing up at Abbey Road.

The band was well-drilled and, speaking to Sullivan-Burke, Leckie recalled very little tone-chasing from McGeoch, whose parts were complex and unusual, but not fussed over. His playing is grounded in rock history only as far as he’s learned the basics in order to see what other shapes he could make from their broken pieces—the languid second-half of The Light Pours Out of Me’s skronky riff, for example, or the almost prog soloing on Burst, which stoutly refuses to overpower the synths.

Often, as with the early ringing chords of Motorcade, it’s more about what he doesn’t do. Space is ceded to Barry Adamson’s showy bassline and Devoto’s dead-eyed vocals until the moment a couple of minutes in that he slams his foot down with a ripping solo. McGeoch had the chops of a pyrotechnic rocker and the rudimentary discipline of a punk.

Ultimate derailment

McGeoch’s time with Magazine fizzled out after three records (the last of them, The Correct Use of Soap, perhaps the best) that were loved by those who found them and ignored by almost everyone else. Frustrated by their lack of commercial success, he moved on. “There was a huge gaping hole [in Magazine] as soon as he left,” Adamson told the Guardian. “It changed the course of the band forever and helped it to its place of ultimate derailment.”

He played in Visage with Formula and Adamson, scoring actual real life hits, before joining the Banshees, where on records such as Kaleidoscope and Juju he revelled in subverting pop shapes and using a more driving, brutish backbone to reinforce his melodic ideas. Later, he worked with the Skids’ Richard Jobson in the vastly underrated Armoury Show and completed a notable post-punk hat-trick by playing in Public Image Ltd, before an affair with drink and drugs became an increasing presence in his life. He retired from music in the 1990s, becoming a nurse, and died in 2004, aged 48.

In McGeoch’s wake, he left a clamoring mass of guitarists whose eyes were opened by the dexterity and imagination of his music. Marr was just one of them, with John Frusciante, Radiohead’s Ed O’Brien and Jonny Greenwood, James Dean Bradfield, the Edge, Mark Arm, Dave Navarro and Steve Albini avowed fans. None of them quite sound like a horse falling off a cliff, though.