Related Tags

All About… The Fender Jazzmaster rhythm circuit

The Jazzmaster’s rhythm circuit has been maligned and misunderstood over the years – they’re far more than just ‘mud’ switches if you know how to use them.

Fender’s ‘offset’ guitars have had an odd trajectory over the years. At the time when the Jazzmaster and Jaguar were introduced (1958 and 1962 respectively), they were top-of-the-line models poised to take over the guitar market – or so the great Leo Fender believed. Over the ensuing years, the models fell out of favour, a fact often attributed to what many players consider to be a flawed bridge design. In truth, this disillusionment was never the guitar’s fault, but rather, a lack of education surrounding fundamental elements of the design, including neck-tilt angle, string gauge, and floating-bridge maintenance.

These oddball axes spent the better part of the last half century overwhelmingly ignored in the guitar arena, hanging on pawn-shop walls at discount prices. They often found homes in the hands of players who couldn’t afford the more expensive Strat or Tele models. However, the eager embrace of surfers, followed by avant-garde freethinkers, post-punk singer-songwriters and underground guitar slingers all combined to coax these misfit music machines into the limelight.

The maverick musicians who fell for the Jaguar and Jazzmaster’s charms form an impressive lineage, which includes Tom Verlaine, Elvis Costello, Rowland S Howard, Robert Smith, J Mascis, Kurt Cobain, Kim Gordon, Thurston Moore, Lee Ranaldo, Nels Cline, Jessica Dobson and Laura Jane Grace, among others. Even more mainstream artists, such as Chris Stapleton and Taylor Swift, have taken the stage with an offset guitar draped around their shoulders, proving once and for all that these instruments deserve their place in the limelight.

Perhaps they haven’t ended up occupying quite the same niche Leo Fender was trying to fill when he introduced them, but like many other so-called ‘failures’ in this industry, the Jazzmaster and Jaguar have found their audience regardless. So great is the surge in the offset’s popularity that an entire cottage industry has sprung up merely to address the guitars’ idiosyncrasies, from aftermarket bridges and pickups all the way to strings wound specifically to tackle the breakage problems associated with the domed screws which secure the vibrato unit’s pivot plate.

Even with the widespread acceptance from musicians, modders, and manufacturers of all stripes, however, there’s still quite a bit of misinformation and mythology to sift through. Of the many misunderstood yet brilliant features these guitars boast, there’s one that still hasn’t garnered the recognition it deserves: the rhythm circuit.

It seems a significant number of players are oblivious to the charms of this unique set of dials, but we’re here to tell you that there’s a whole universe of utterly usable tones lurking there between wood and wire. In order to fully understand this underutilised part of the Jazzmaster and Jaguar wiring scheme, we’re going to need to take a trip back to the early days of Fender in Fullerton, California.

Production line

It’s no secret that Fender had trouble keeping up with orders in the early 1950s. Clarence Leonidas Fender always was more of a thinker than a foreman, sequestered in his laboratory where he chased ideas; the business side of things was a problem for others to solve.

His fixation on minor improvements meant dealers often had to wait for stock, which proved an endless source of frustration for Don Randall, who handled sales and distribution of the entire Fender catalogue. By the time the Stratocaster hit the market in 1954, it became increasingly clear that the lack of organisation in the factory had to change in order to keep up with demand.

So, while Leo Fender gets the credit for inventing the world’s first mass-produced solidbody electric guitar, it’s Forrest White who deserves recognition for keeping that mass production running smoothly.

Born in West Virginia in 1920, Forrest White spent his formative years in Akron, Ohio where he wrote patriotic songs and pursued schooling in industrial engineering and business management. During World War II, Forrest worked in numerous capacities for the Goodyear Aircraft Company; afterwards, his love of music and a desire to work in the guitar industry led him to the booming scene of Southern California, where he sought out Leo Fender and his shop. His background in both music and business would eventually make him an ideal choice for plant manager – a job title which simply didn’t exist at Fender before White came along. However, it would take a few years and a handful of visits for that to come to pass.

On one such visit in 1951, Forrest showed off a 10-string steel he built using leftover parts from a scrapped father-and-son project guitar, and among those parts was a unique pre-set tone-control circuit. Forrest’s work obviously left an impression on Mr Fender, who hired him in 1954. White’s presence at the factory was felt almost immediately, where he streamlined the manufacturing process, overhauled the component resupply system, and introduced employee incentives to boost morale. So crucial was White’s impact that Leo would name a line of lap-steels and amplifiers after the man. A few years later, during the design phase, it was Forrest’s homespun two-tone wiring scheme that inspired the Jazzmaster’s rhythm circuit.

Inside the rhythm circuit

The rhythm circuit can be most easily understood as putting the ‘jazz’ in ‘Jazzmaster’. The intent behind it was to offer players a pre-set rhythm sound for the darker tones commonly associated with the genre.

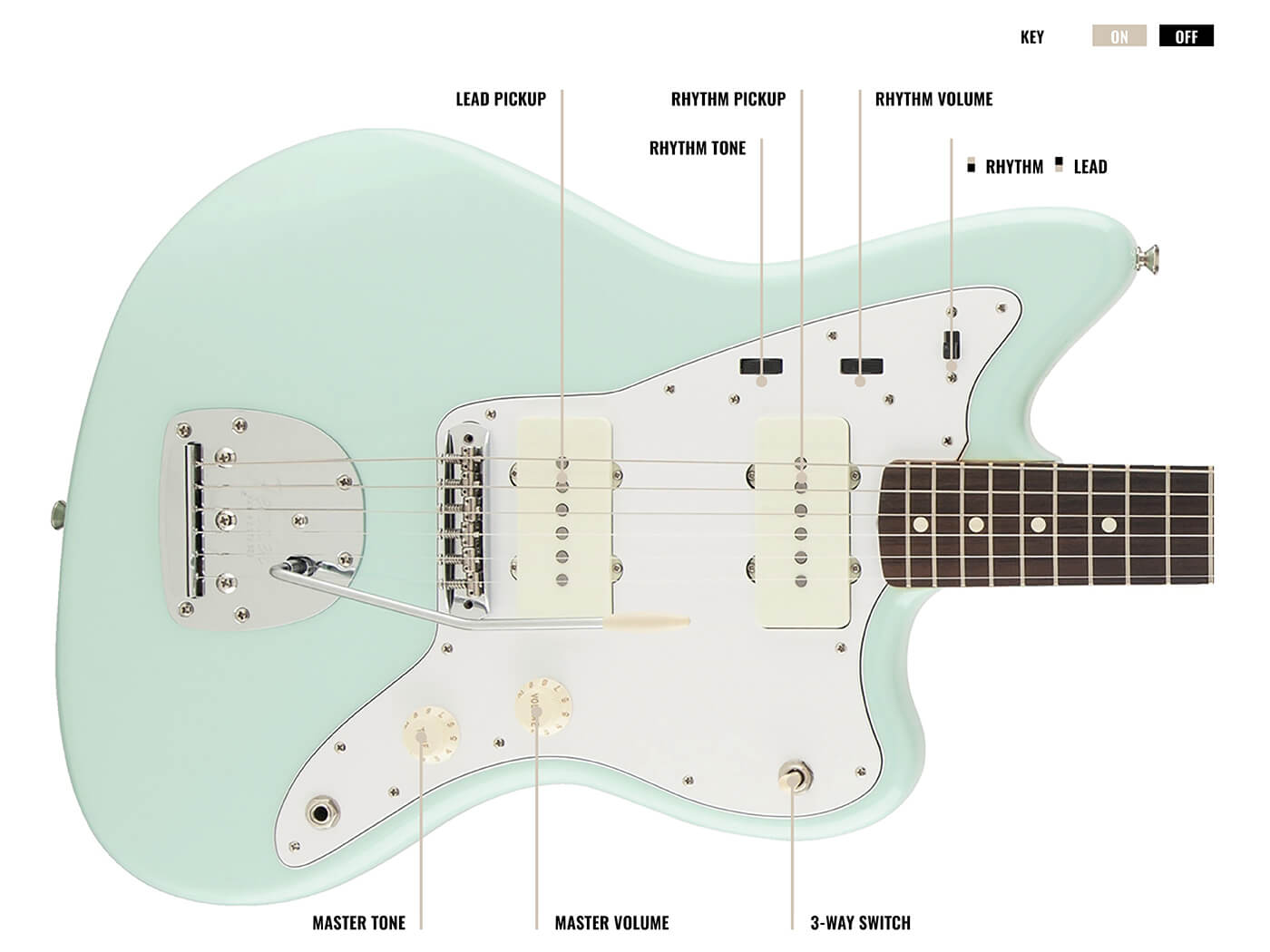

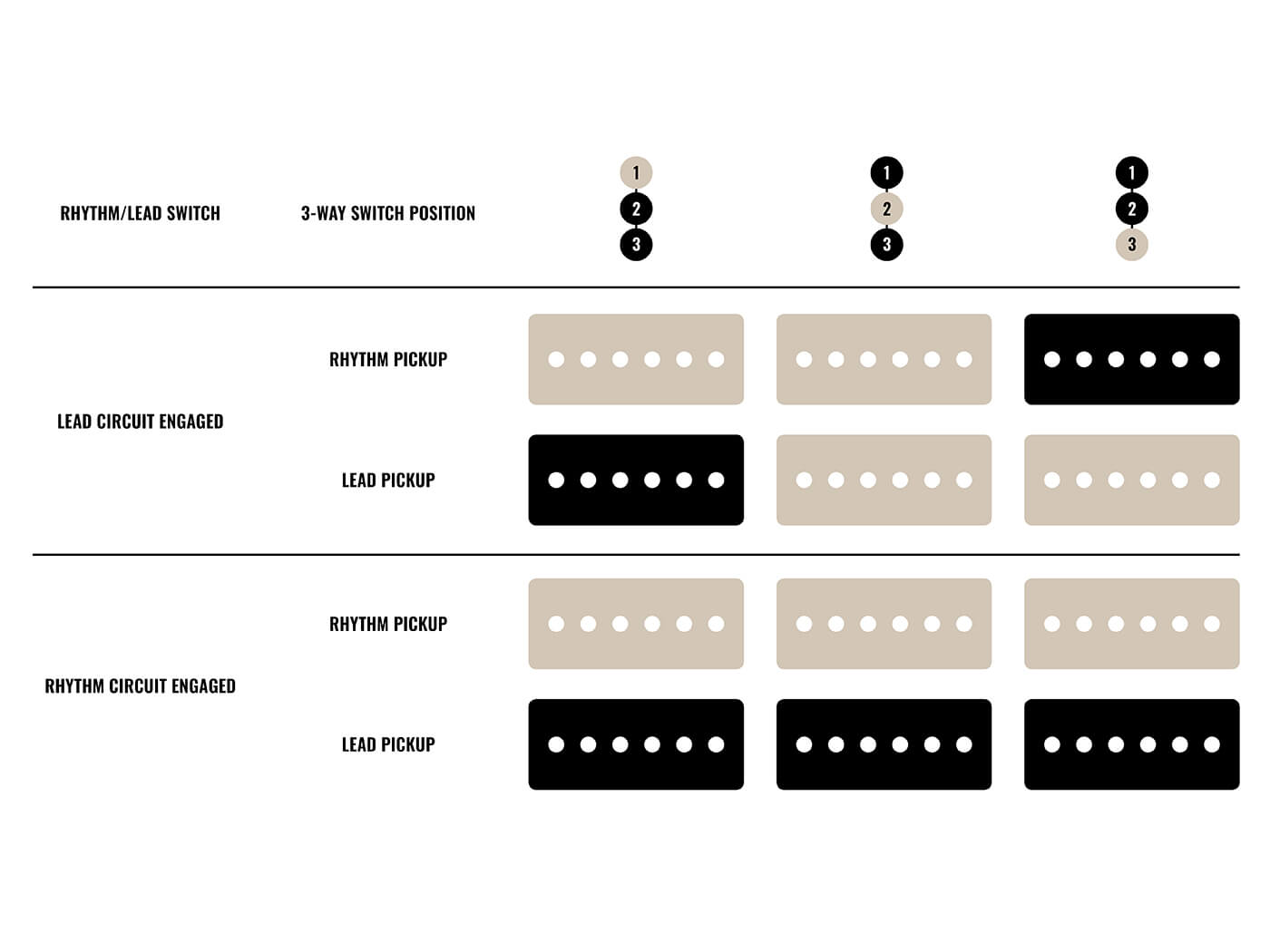

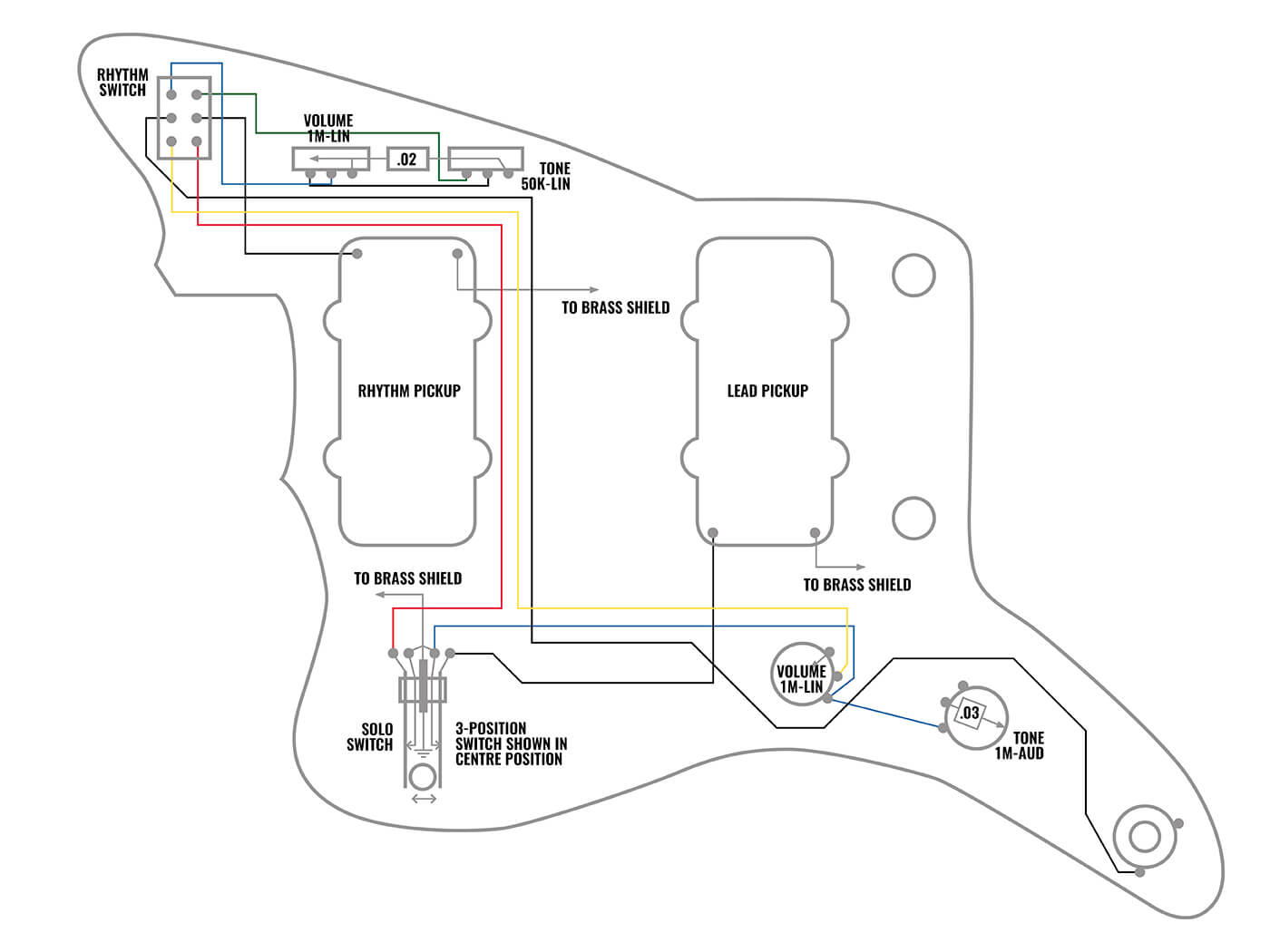

When the switch is in the ‘up’ or ‘on’ position, the neck pickup is singled out, then routed through a separate set of controls consisting of a 1 meg volume and a 50 kilo-ohm tone paired with a .02μf capacitor. The major difference between this and the standard controls is the 50k tone pot, which is like taking zero through two from a standard tone knob and using that as the entire range of high-end roll-off.

As a result, the circuit emphasises bass frequencies and drastically tames treble, but also boasts an inspiring selection of colourful sounds within its narrow sweep. These pots are controlled via thumbwheels which poke through the bass side of the pickguard.

When it’s time to step out for solos, the user simply disengages the circuit, activating the brighter and more familiar control layout: a toggle selector switch for both pickups, 1 meg volume and tone controls, and a .033μf tone cap. All of this works exactly as you’d expect on any other guitar, which is perhaps one reason the additional controls never caught on.

Switch killed, disengaged

The notion of two discrete tone circuits in one guitar should have been revolutionary, considering these were the days before outboard effects. Back then, a guitarist’s rig consisted of the guitar, a cable and an amp loud enough to be heard over a big band. If the player needed boost, they turned up.

At the time, few other companies seemed to be interested in trick controls; Supro had a few models which allowed for selectable sounds more in line with Fender’s Esquire wiring, and of course, Gibson’s Les Paul had separate volume and tone controls for each pickup. Yet, neither of these options come close to the proposed versatility of the Jazzmaster wiring scheme.

Perhaps the most damning reason for the tepid response to the rhythm circuit is the fact that jazz players never truly embraced the Jazzmaster. Though Leo Fender succeeded in his goal to create a solidbody guitar with the string geometry of an archtop, players of the day were largely traditionalists who preferred to stick to the hollowbodies they were used to; they simply didn’t want what Fender was offering. Despite the circuit’s later inclusion on the Jaguar, it would seem that even surf players of the day rarely found a compelling use for those offbeat controls.

Some players from other genres may have been more receptive to the rhythm circuit’s potential, yet the vast majority either had no need for it, or found it to be more of a burden than a boon. Due to the placement of the switch, unintentional activation of the circuit remains an issue for today’s more acrobatic strummers, so it’s not uncommon to see the switch area taped off entirely.

Another popular fix is to break off the eraser of a pencil in the pickguard cutout, effectively limiting the movement of the switch. Others opt to disconnect the circuit completely, and some have claimed improved tone as a result. The jury’s still out on that one, we’re afraid.

Rhythm method

When considering its applications for modern musicians, it can’t be overstated how good the rhythm circuit is for, well, rhythm! Woolly and sombre, the additional tone network stands in stark contrast with the brightness of the traditional lead controls, favouring diminished attack and robust low end, which can be highly effective in the right circumstances.

Today’s jazz players should take some time to fully understand the range of the circuit, because it excels at providing the depth and definition that works so well in all types of modern jazz. Rolling back the tone all the way is perfect for doubling basslines, much like the neck position of the original Esquire blade switch.

If you’re a blues fan that just can’t get enough of Eric Clapton’s famous creamy lead tone, grab a Jazzmaster and a good Plexi-style overdrive pedal. With the circuit activated, it’s as good an approximation as you’re likely to hear from a single-coil guitar. It’s also a great way to punctuate more explosive power-pop song sections by using the preset circuit controls to coax syrupy clean sounds from cranked single-channel amps. Dial back the volume on the roller, leave the tone at full, and use the onboard switch as channel two… or turn down the volume entirely and use it as a kill switch.

Pedal fanatics should also rejoice: the rhythm circuit loves effects! Teamed up with a bright overdrive and modulation, the RC is perfect for moody verses and atmospheric passages (think Radiohead’s I Might Be Wrong). The rich clarity of the neck pickup imparts its own texture to volume-pedal swells, and complements ambient reverb and delay settings for brooding, aphotic tones. Employing a polyphonic pitch generator also yields some of the best guitar-as-organ sounds around, thanks to the rhythm circuit’s rejection of tinny brightness that can create nasty transient artefacts which confuse even the best-available pedals.

Experimental types should particularly enjoy the sounds on tap from the preset controls. Pitch-shifters of any kind seem to prefer the neck pickup, but the low-end emphasis here makes octave-down effects sound massive. Try running the rhythm circuit into a Whammy and through either a Z.Vex Fuzz Factory or a Muff-style fuzz box. You’ll be greeted with downright apocalyptic tones that could herald the end of days – mix with delay and reverb to taste. Heavy-duty amps are encouraged, but not required.

In the quest for tone, it pays to keep an open mind. Switch up your gear, challenge your preferences, and try everything, no matter your skill level. If you have access to a Jazzmaster or Jaguar, we humbly suggest you explore the oft-overlooked controls which live at the northernmost peak of your pickguard. The ability to go from dark to bright in an instant can be an exciting way to add some tonal variety to your repertoire. There are also a number of interesting ways to mod the circuit – a conversation for another day.

Check out our picks of the best offset guitars under $1,000, or read our review on the Fender American Original 60s Jazzmaster.

For more Jazzmaster articles, click here.