Related Tags

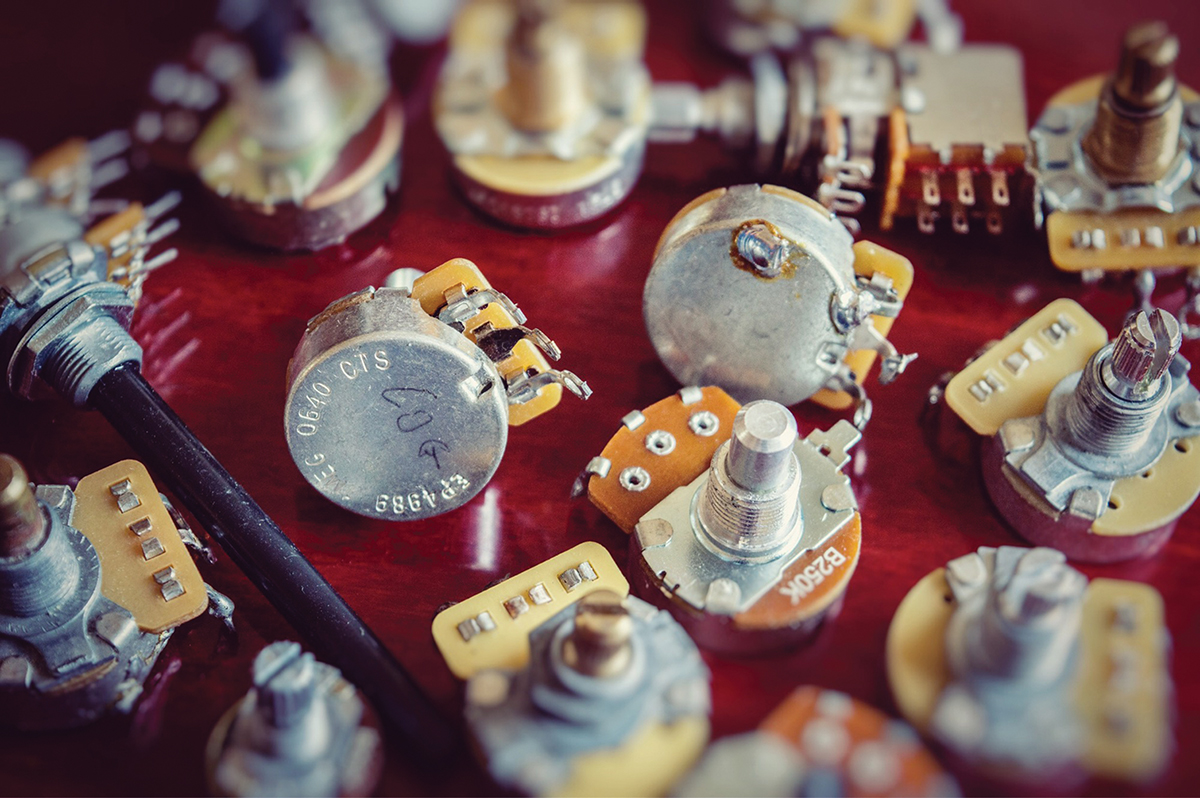

All About… Potentiometers

Your tone and volume pots can have a significant impact on your sound, but how much do we actually know about what makes those controls work?

There are things in life that affect us all, yet we generally prefer not to think about them. In the wider world, these may include terminal illness, death and Brexit, and in the guitar world we might suggest speakers, straps and potentiometers. Considering that the transformative effect of a five quid pot swap may greatly exceed that of a costly pickup upgrade, that’s an oversight.

If you play electric guitar, there will almost always be one or two potentiometers between your pickups and your pedalboard or amp input. Even if you use your volume pot more as an on/off control than for volume adjustment per se, it has a significant impact on tone regardless. On the other hand, if you do like to control an amp using your guitar volume, you may already be aware that not all volume pots are created equal.

A potentiometer can be used in one of two ways – as a voltage divider (fig 1) or as a variable resistor (aka rheostat – fig 2). Potentiometers in guitar circuits are used to control volume and tone. For volume applications, they are configured as voltage dividers and for tone they are wired as variable resistors.

Volume Pots

Look at volume control wiring, and you’ll notice how all three connection lugs are used. One of the outer lugs will be connected to the hot wire from a pickup or, in the case of Strat-style master volume set-ups, the output from a pickup selector. The second outer lug is wired directly to ground and the centre lug serves as the pot’s output connector. The outer lugs are connected to one another by a strip that has a fixed resistance.

Theoretically, the resistance should be stamped on the outside casing of the pot, but the stated resistance and actual resistance rarely correspond. If you want to determine the actual value of a potentiometer – out of circuit – connect the test wires from a multimeter to the pot’s outer lugs. Resistance will remain unchanged even as the pot is being turned.

The centre (output) tag is called the ‘wiper’ and it is connected to a conductor that makes contact with the resistive strip. Turning the pot changes the position of the wiper on the strip, which effectively divides the resistive strip into two resistors.

When the wiper is set around the halfway point, there will be resistance between the wiper and the input and between the wiper and ground. Therefore, some of the input voltage will appear at the pot output while some will go to ground. This is how volume reduction is achieved.

Turn the wiper tag all the way up to the input tag and there will be little or no resistance between the two of them. This is because theoretically, the voltage readings on the input and output tags will be identical. As the wiper is moved towards the ground connection, the resistance between the wiper and ground decreases until it reaches zero. As resistance drops, more of the input voltage flows to ground, which lowers volume until, eventually, all of the input voltage goes to ground and none appears at the output.

Tone Pots

The tone control is easier to understand because only two tags are used – the wiper and one of the outer tags. The spare outer tag is left unconnected, and is frequently snipped off entirely.

In Les Pauls, one lead wire from a capacitor is wired to the volume potentiometer’s output (or input) and the other wire is soldered to an outer lug on the tone pot with its centre lug connected to ground.

When the wiper is turned all the way around to the input lug, the resistance between them falls to zero and all of the high frequencies that have flowed through the capacitor will go directly to ground. This corresponds to the tone control being rolled fully back.

At the other extreme, the resistance between the input and wiper will roughly coincide with whatever it says on the pot casing. This is equivalent to the tone control being ‘unused’.

But if you’re thinking that some of the high frequencies must still be finding their way to ground if the resistance is only 250k or 500k, you’re correct.

This is why there is always some treble bleed whenever tone controls are installed. Some people prefer to use no-load tone pots because they take the tone control completely out of circuit when it’s not required and a brighter sound is achieved.

Pot Taper

The relationship between wiper position and resistance between the wiper and input lug determines the ‘taper’ of the pot. So, if you can read 500k on your multimeter at one extreme, zero resistance at the other and exactly 250k at the half way point, you have established that the pot has a linear taper and you may notice a ‘B’ prefix along with the pot value.

If the resistance increases slowly, remains lower than 250k at the halfway point, and increases rapidly towards the end of the resistive strip, then the pot has a logarithmic response. This is generally referred to as ‘log’ or ‘audio’ taper’ and an ‘A’ prefix is sometimes used to denote this.

A third type is known as ‘inverse log’ or ‘negative log’ because resistance increases rapidly and will exceed 250k long before the wiper reaches its centre position. However, the rate of resistance change decreases as it nears maximum. An ‘F’ prefix is sometimes used for these pots, but we are not aware of them being used in guitars.

Let’s go back to the linear pot and set at the halfway point. Although the resistance readings between the output lug and the ground and input lugs are identical at 250k, it doesn’t actually follow that the volume is halved. The pot may be linear, but the way our ears perceive volume isn’t.

For our ears to perceive a halving of volume with the control at the midway point, the pot actually needs to be logarithmic. So, log pots are generally preferred for volume because signal level ramps up, and down more smoothly that it does with linear pots. But not all log pots are the same.

The most widely used guitar pots are made by CTS, and they offer ‘modern’ and ‘true vintage’ taper log pots. The difference is described as follows – “vintage pots are at 30 per cent of their total resistance at five on the dial, whilst a modern pot is at 15 per cent”.

Similarly, manufacturers such as Bourns, Alpha and Alps may all have their own log response. Ultimately, it’s a matter of trying different types to decide what works for you.

The same can be said for tone pots, but things are less clear cut. Some prefer a smoother response, while others want a more dramatic wah-type effect. If you want the former, go linear and if you want the latter, go log.

The Resistance

There are well-established conventions about matching up pots and pickups that go back to the earliest solidbodies, but there’s nothing compelling you to stick with them. As a rule, bright single-coil pickups will be used with 250k pots and darker humbuckers with 500k pots.

It’s generally assumed that lower resistance pots sound brighter, but it’s actually the way that the pot interacts with the resistance, inductance and capacitance of pickups, tone controls that determines the brightness.

With regular passive circuits, there is always some treble roll off, which tends to begin at around 3.5k with humbuckers and 4.5k with single coils. The interesting bit is the resonance peak at the cutoff frequency and the higher the potentiometer resistance value, the greater the amplitude of that peak.

Any sound engineer will tell you, 3k to 5k is a pretty crucial frequency range for guitar tone. It’s where you find clarity and the cut that gets you heard through a mix. But if your guitar is loaded with bright pickups, or your amp and speaker have a lot of brightness, that useful cut can turn to harshness and shrillness.

Maximum resonance will be achieved with a one meg volume pot and a no-load tone pot. A pair of 100k pots will produce the flattest frequency response up to the cutoff frequency. Mix and match values to find your ideal tone and feel free to deviate from the usual. Also check the value of the pots in your guitar before changing pickups because countless Les Pauls have been buried in mud by Gibson’s decision to use 300k pots.

Buying tips

To close, here are some considerations for pot-swapping. If your control knobs are push-on types, you need a split shaft. Knobs secured by grub screws require solid shafts. Shaft length is important too because long shafts are often needed for carved top guitars such as Les Pauls.

If you enjoy using the controls for rapid adjustments, volume swells and wah effects, find out about the feel. Some pots are looser than others, which is why Yngwie Malmsteen prefers Bourns pots. You can buy them for about £3 at RS Components. And for all the southpaws out there, don’t forget to buy left-handed pots!

For more information head over to http://www.rs-components.com/