How to play Red Hot Chili Peppers-style chords Part 2

This time around we examine John Frusciante’s chord voicings and sequences.

Image: Joey Foley / FilmMagic

John Frusciante stands out as the most influential of the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ guitar players. In Part One of our examination of the Stratocaster-slinger’s guitar style, we took a look at his fingerpicked chords. In Part Two, we concentrate on his chord voicings and sequences.

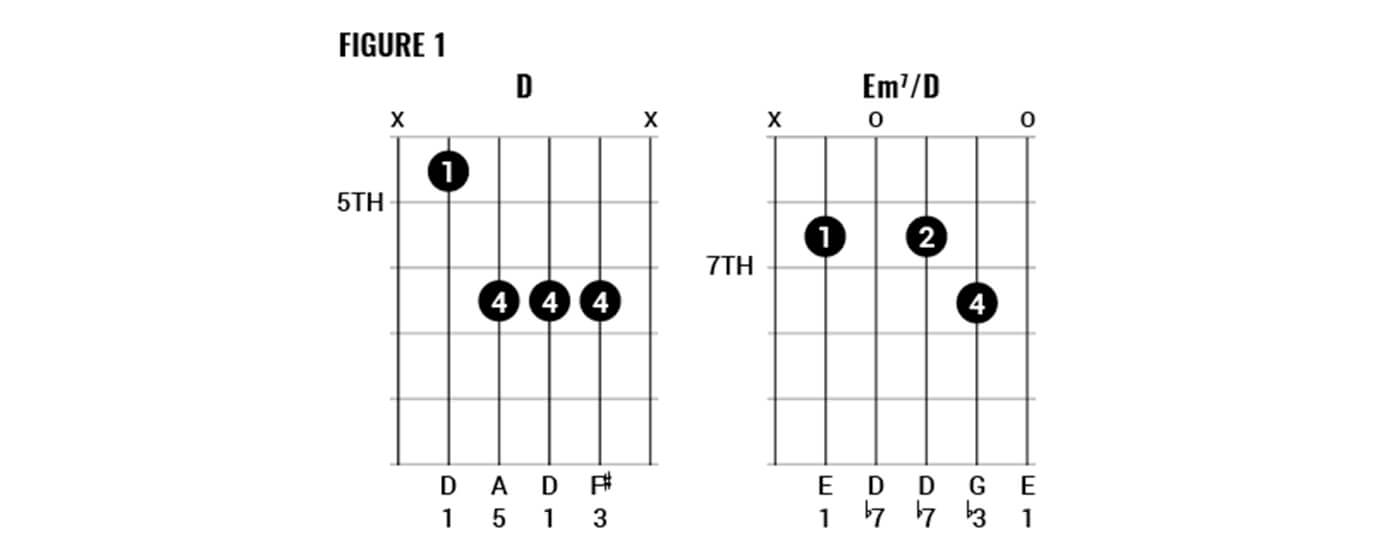

Looking at Figure 1, you might say we have a normal chord followed by an abnormal chord. The D major chord is a common movable shape that can be played all over the guitar. The Em7/D voicing is fixed in this one position, mixes fretted notes with open strings, unusually doubles the minor seventh and has the open fourth (D) string as its bass note.

Give each chord two bars of vigorous strumming on your electric. You’ll need tidy fingering to get all the notes of the Em7/D to sound cleanly. Also, add some compression – Frusciante is a known user of the famous little MXR Dyna Comp. Em7/D is ‘E minor seven with D bass’. We call this type of chord a slash chord; the note that comes after the forward slash is a specified bass note.

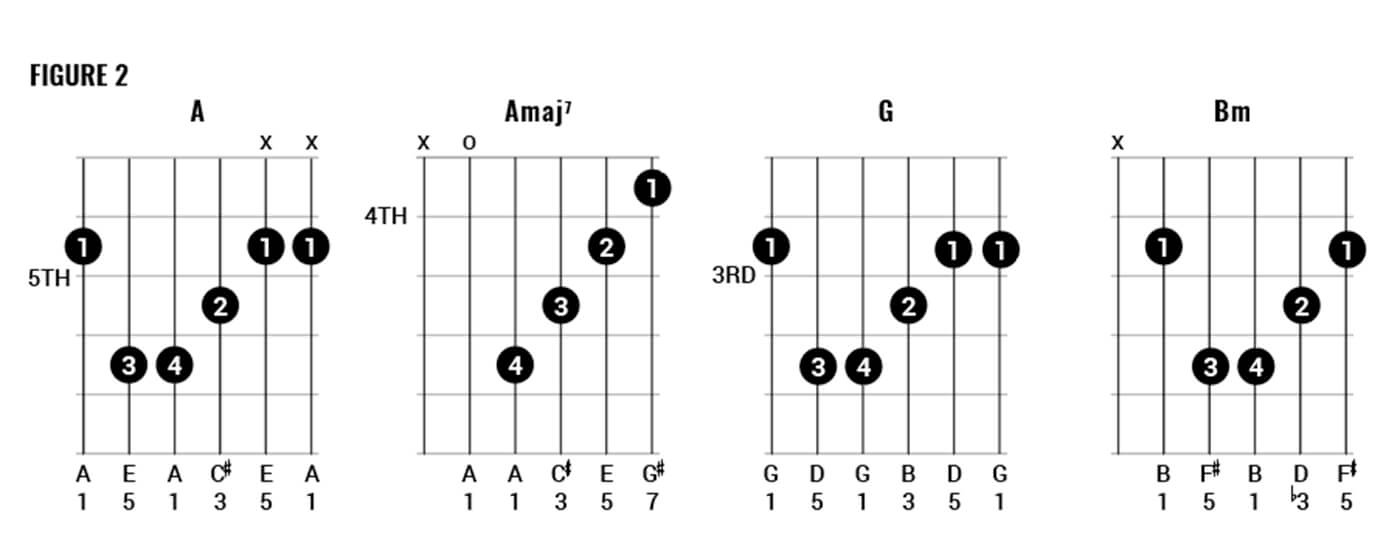

The RHCP are masters of four-chord sequences. Fortunately, they very rarely use the commonplace I-V-VI-IV, which in the key of A would be A, E, F#m, D. In Figure 2, we have a four-chord sequence in A that bears no relation to the above, consisting of I-Imaj7-♭VII-II. While most of these barre chord shapes are part of the language of rock guitar, major-seventh chords are unusual, belonging more to jazz and soul.

If you have problems moving from the A barre chord to the major seventh, notice that your pinky is already in the right place for the second chord, so leave it there while you rearrange the other three fingers. Also allow your thumb to come over the edge of the fingerboard to touch and mute the sixth string, so that you can strum and hear the open A, not E, in the bass.

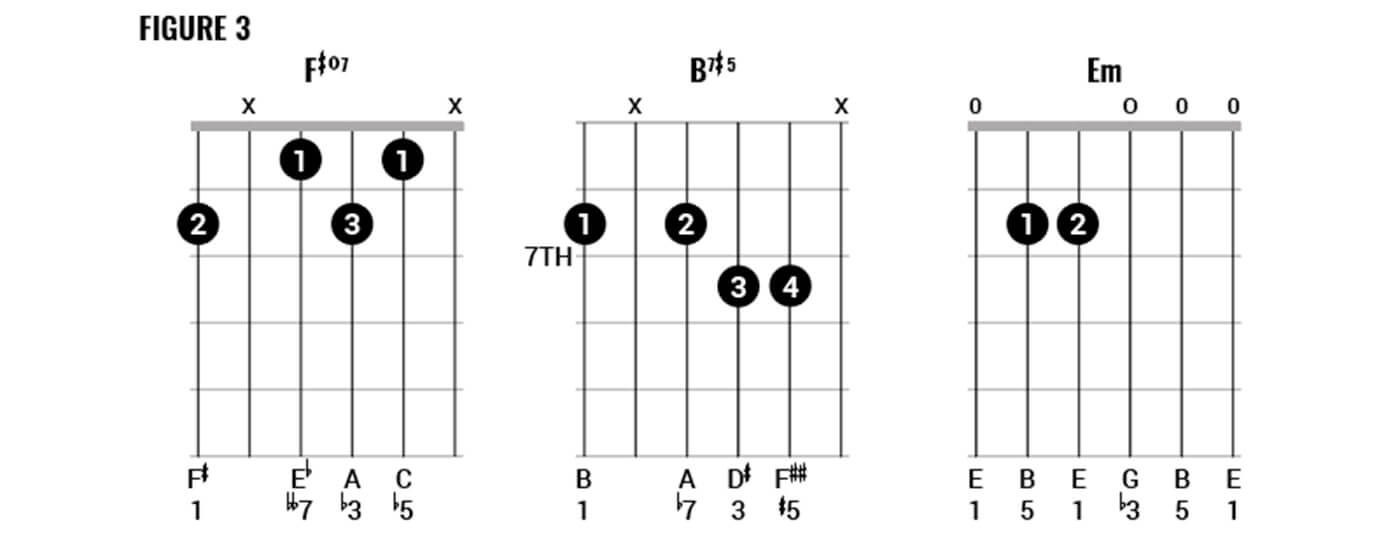

If you loop Figure 2 around a few times, you may find that you need a way out. Cue Figure 3, and some more of those unusual Frusciante chords. Give the first two chords a bar each, and then crash into the big open-string E minor chord and let it ring for two bars. Repeat Figures 2 to 3 as you like; you could even try starting with Figure 1.

In our previous instalment, we mentioned how diminished chords are rare; we probably don’t need to mention that 7#5 chords are just as exceptional. Except, that is, in Frusciante-land, where in Part One we found a B augmented triad, which is a very close relative of B7#5, which you could describe as B augmented with a seventh.

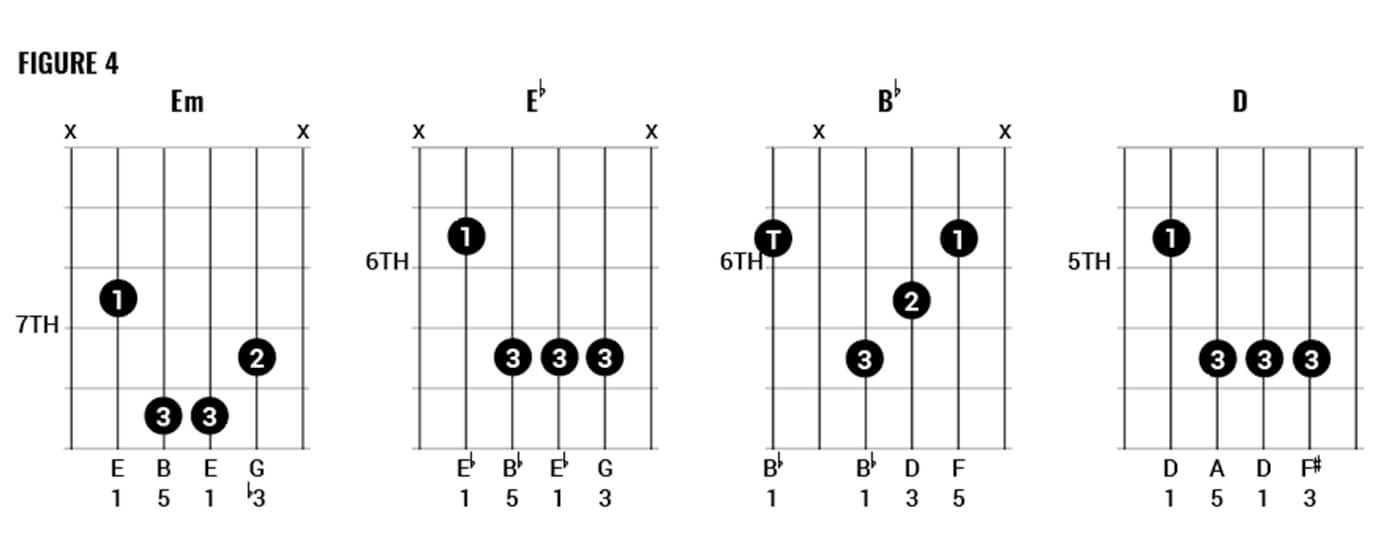

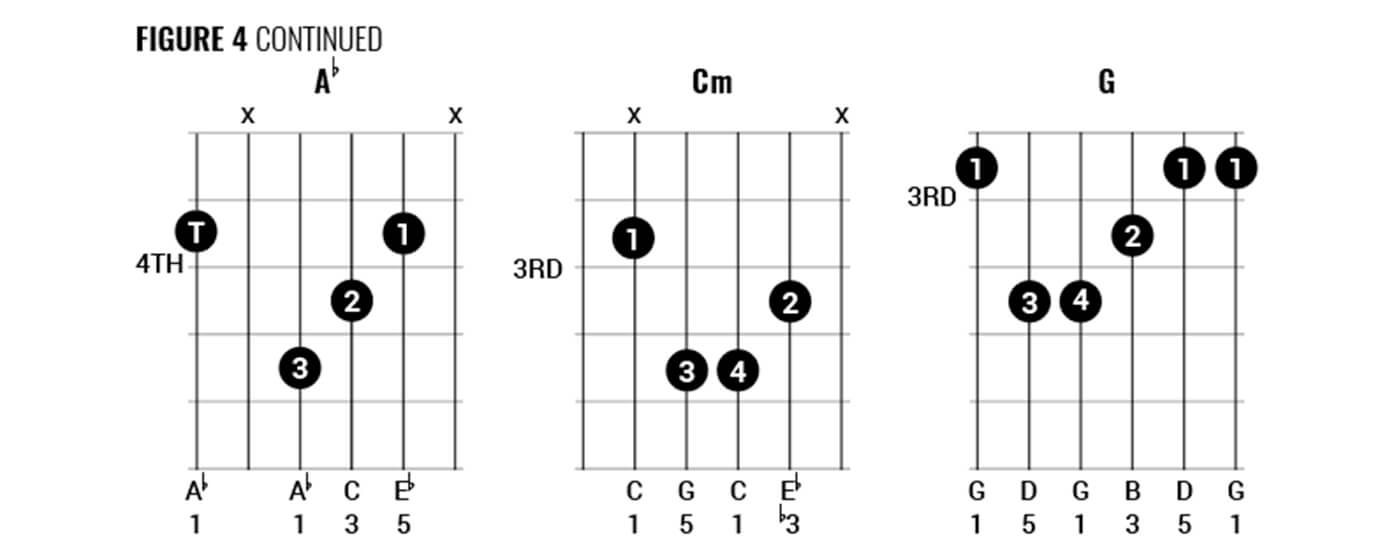

Figure 4 is a dreamy sequence of chords which you might use to play a song out at the end. There are seven chords which make eight bars of music by going back to the A♭ chord in between C minor and G. The chords themselves are not unusual, but we have included this sequence because harmonically speaking it is something of a mystery. There is only the most tenuous relationship between these chords.

Allow us to explain. E minor is in a different key to E♭. While there is a relationship between E♭ and B♭ (I-V), the next chord is D – different key again. The A♭ chord is in another new key, in which C minor is chord iii. At a stretch, you could say the last four chords are Im-VI-Im-V in C minor, but at the end the G major chord leads back to… E minor. Play it and hopefully, you will hear what we mean.

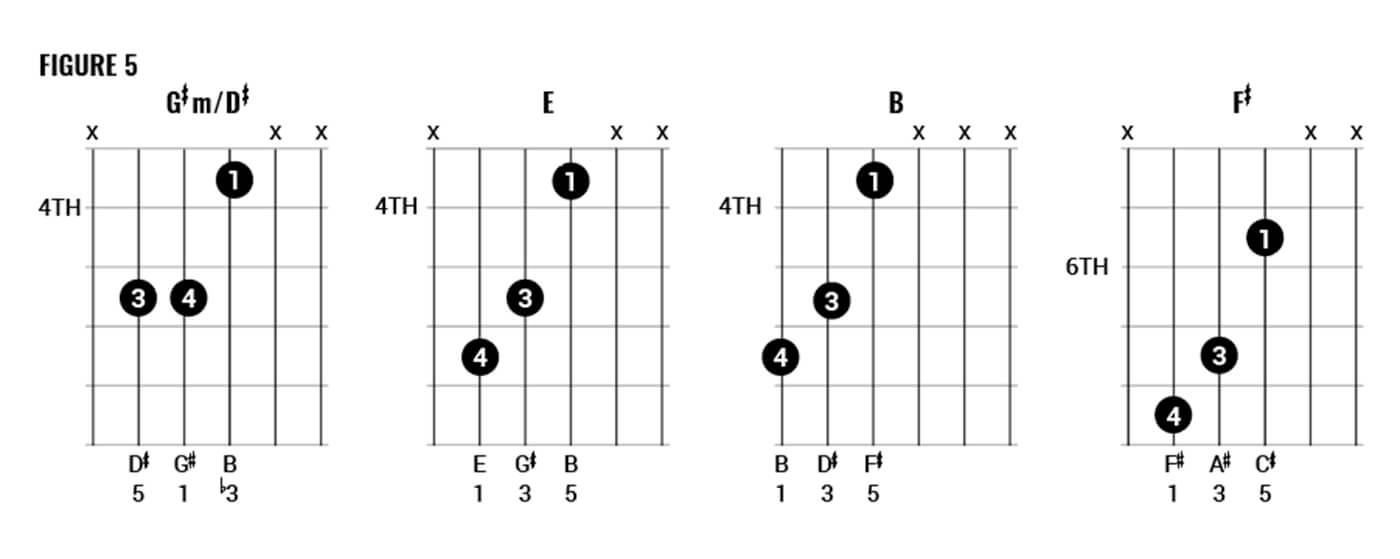

Returning to the four-chord sequence for a moment, a trick that you can try is to start in the middle with chord vi. That makes it VI-IV-I-V. You can see this in Figure 5, where is played in the key of B, with the added flavouring of the G#m chord having D# in the bass. Technically, that makes it a second inversion, which is what you get if the fifth of the chord is the bass note.

The final chord in Figure 5, F#/A#, is for you to play the second time around; this time, it’s a first inversion, with the third of the chord in the bass, keeping things interesting by adding a variation on the repeat. Try playing these chords as arpeggios, adding a hammer-on/pull off combination two frets up from the top note of each chord.

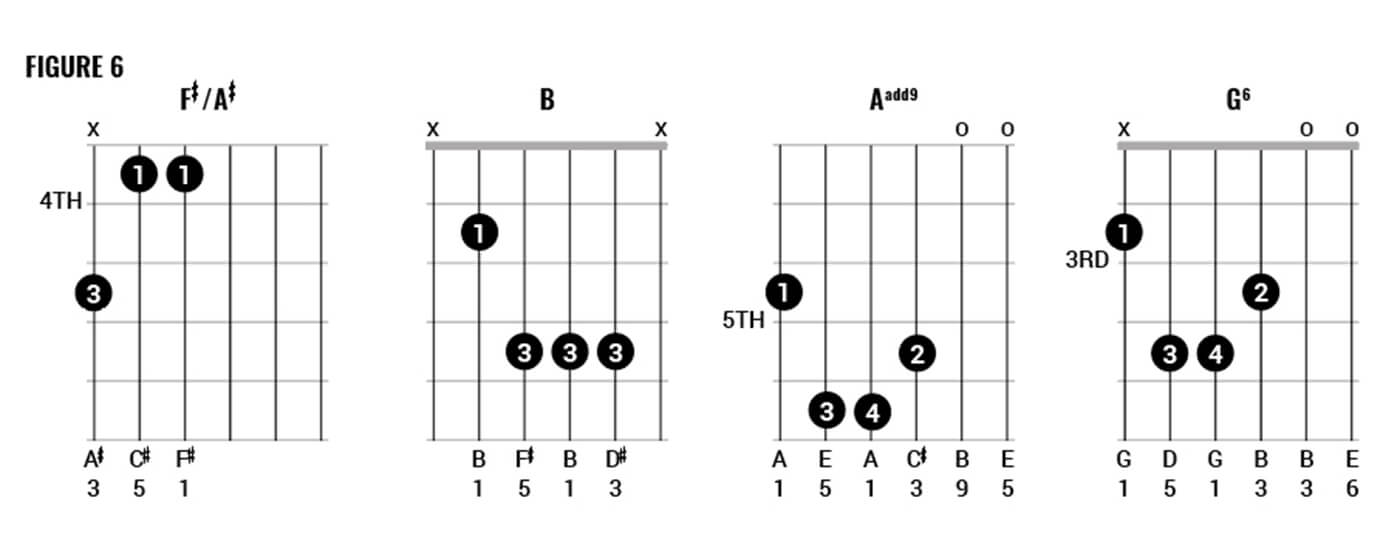

We couldn’t leave Fruscianti’s world without adding a few more chords which mix fretted notes and open strings. In Figure 6, start on B major, slide up three frets to the D major shape from Figure 1 and then play the next two chords with the open top strings and let ring. Enjoy that great splashy, crunchy sound!

Check out more lessons here.