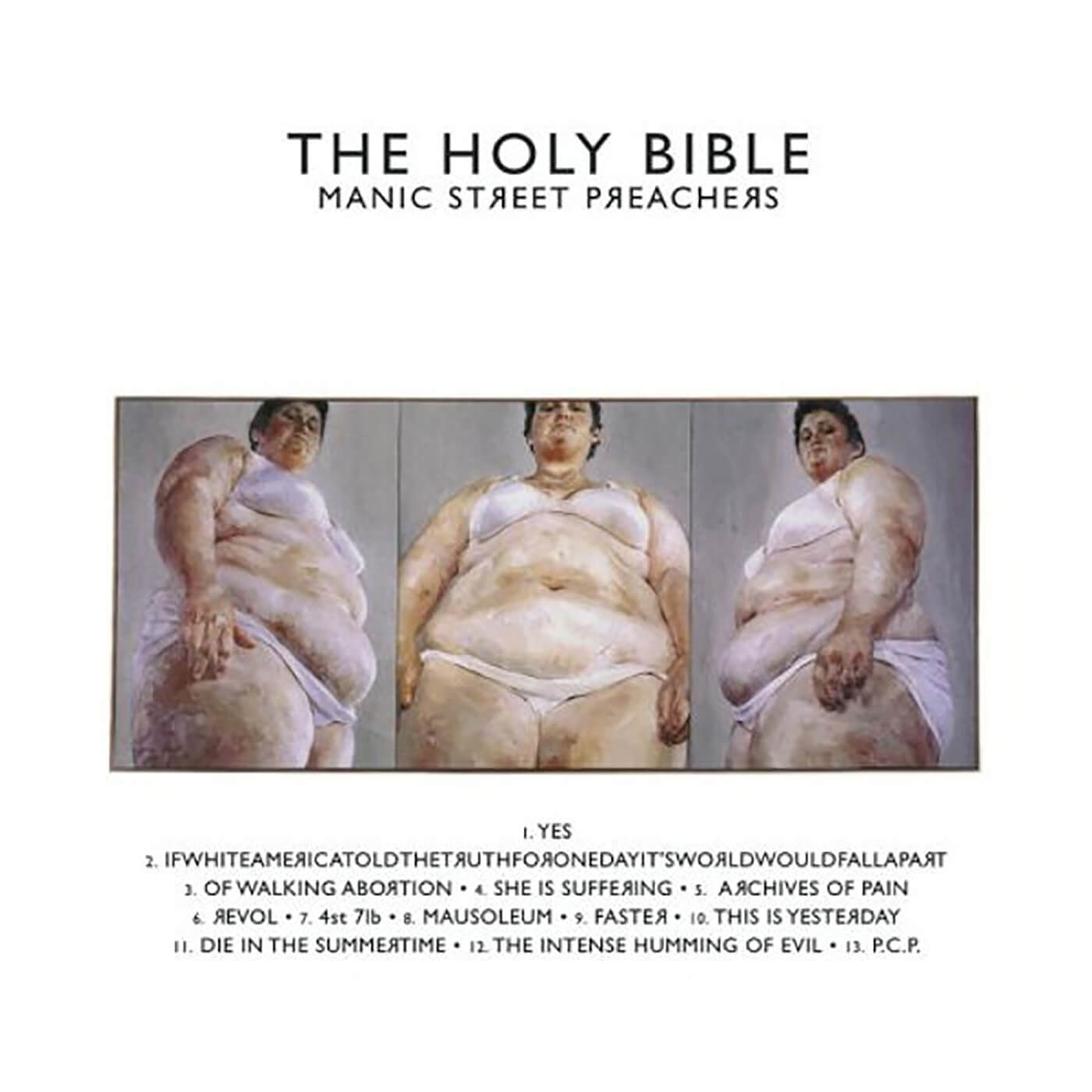

The Genius Of… The Holy Bible by Manic Street Preachers

The magnum opus of a brilliant, but tormented mind. The Holy Bible found the Manics re-tooled from nimble glam rock exhibitionists to harbingers of looming apocalypse.

Image: Dave Tonge / Getty

The most groundbreaking moments in music have rarely stemmed from those who’ve rigidly stuck to the blueprints for commercial success. It’s those artists who’ve made tough choices and hard-swerves into uncharted territory, that have made the most important dents.

Few records have impacted listener consciousness quite like the Manic Street Preachers’ third LP, The Holy Bible. A marked departure from the radio-friendly sheen of the preceding Gold Against The Soul, here was a document less preoccupied with garnering radio airplay than it was with ripping apart the foundations of the political systems that shaped an expanding, globalised world. Its broader conceit convincingly predicted the western world’s slide into a barbarous, fascistic future, while its citizens stand idly by, opiated by consumerism.

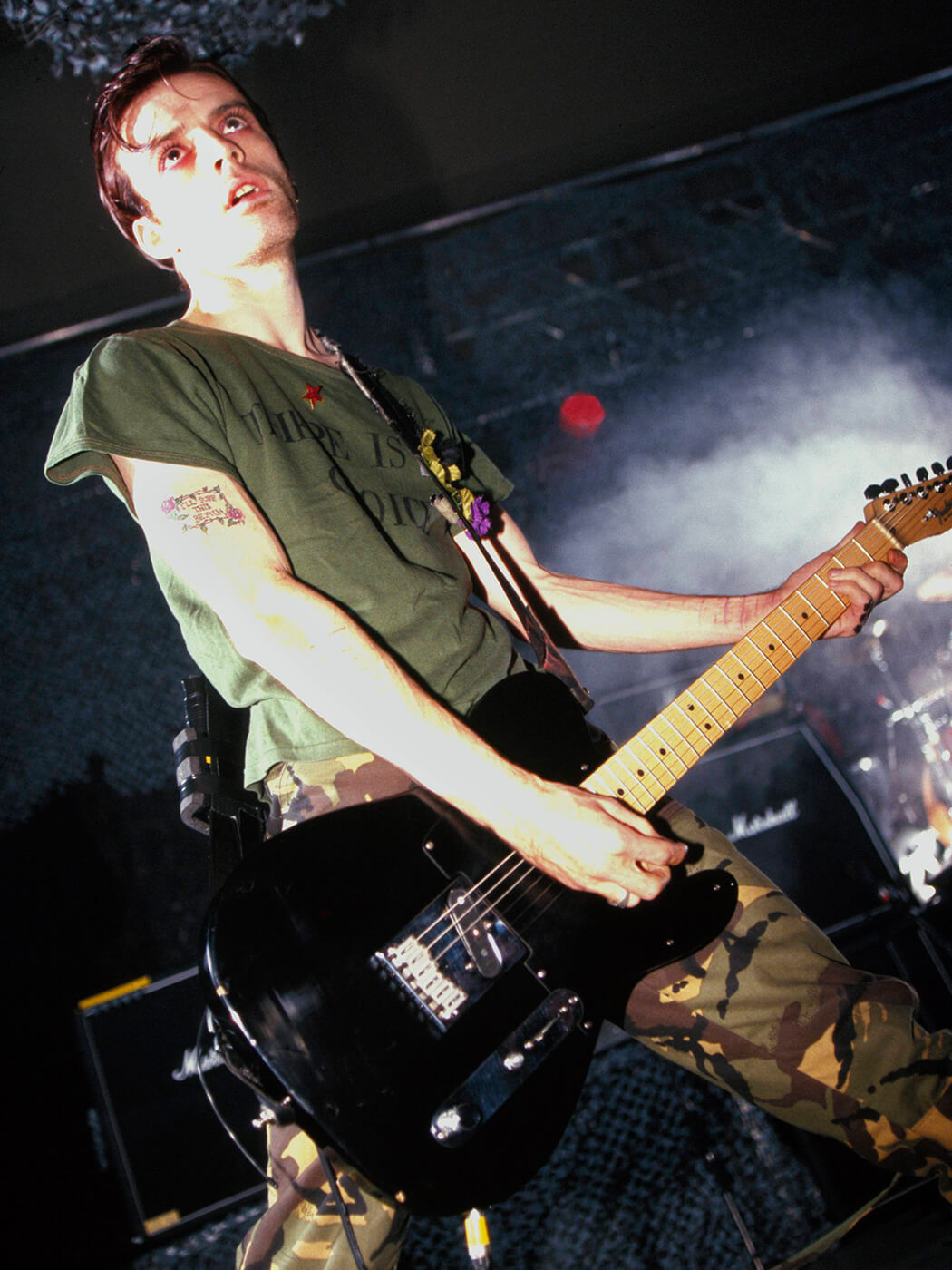

In parallel to its bleak broader concerns, The Holy Bible also serves as an act of brutal self-examination, with the band’s mercurial lyricist and chief aesthete Richey Edwards, regularly directing his wrath at himself throughout the album’s run-time, deconstructing his mental and physical health, most pointedly on the heart-rending 4st 7lb – a song informed by his own battles with anorexia.

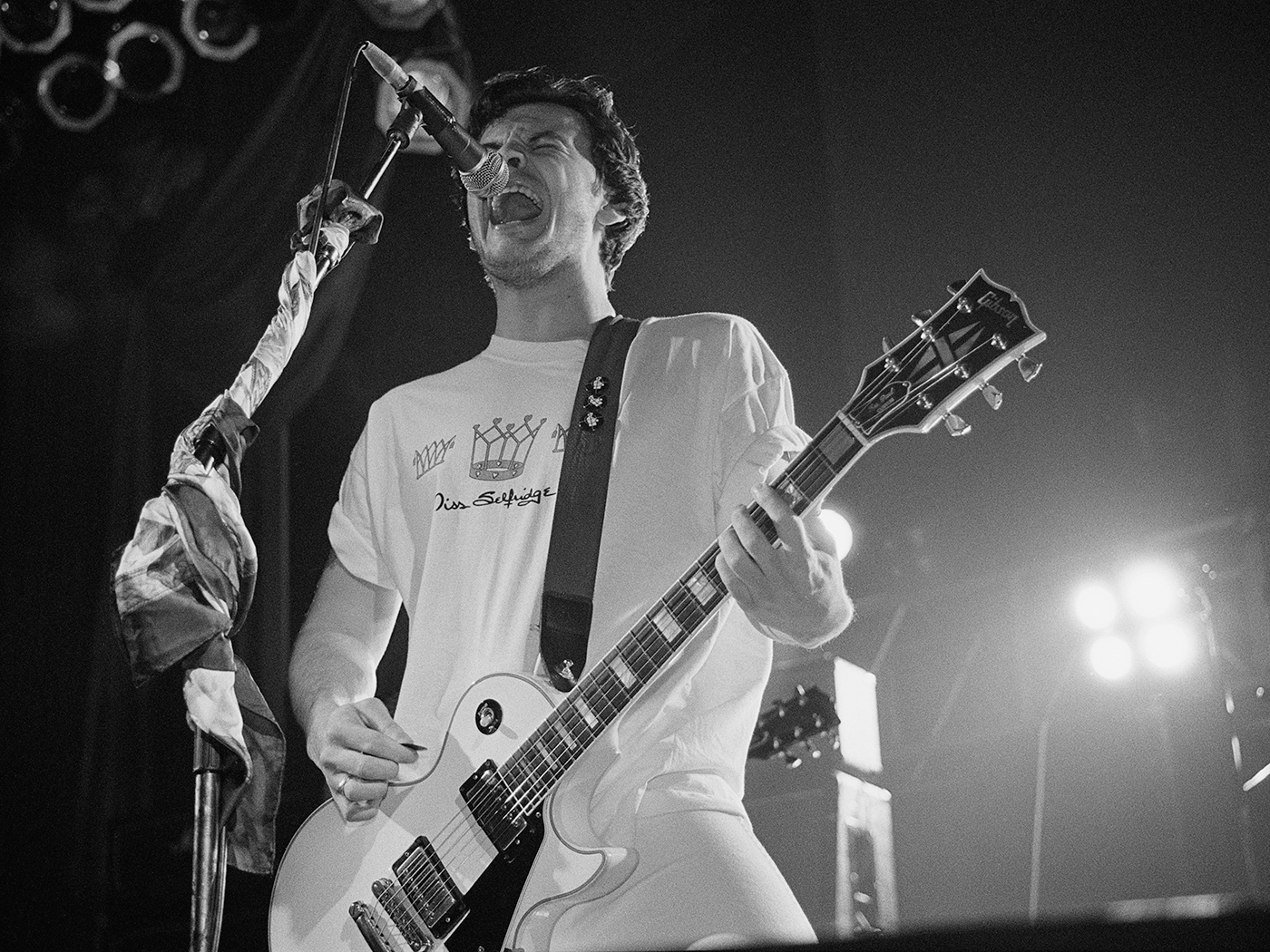

Charged with injecting Edwards’ disordered lyrical outpourings into suitably boiling arrangements, the Preachers’ central guitarist, James Dean Bradfield was the album’s musical lynchpin, and crafter of its many blistering guitar sounds. He bound Edwards’s often stream-of-consciousness tirades with a harsher edged gothic veneer – a far cry from the bright day-glo glam of the preceding album.

In a cramped Cardiff studio, Bradfield carefully sequenced complex broadsides of intimidating, sledgehammer power chords, coupled with melodic, serpentine leads and petrifying squalls of tension. As Bradfield said to journalist Ned Raggett at the time (later published by The Quietus) “We did it really quick. It’s more direct. I don’t think it makes concessions to the listener at all. It’s really honest, and it just goes for it.”

Sadly, it’s a record that’s often evaluated in the context of what happened next, with Richey Edwards’ tragic disappearance (and the eventual assumption of death) overshadowing many perceptions. Assessed on a purely musical level, The Holy Bible still stands as the Manic Street Preachers’ most blazingly intense, harrowingly dark and profoundly compelling work.

Lust, vice and sin

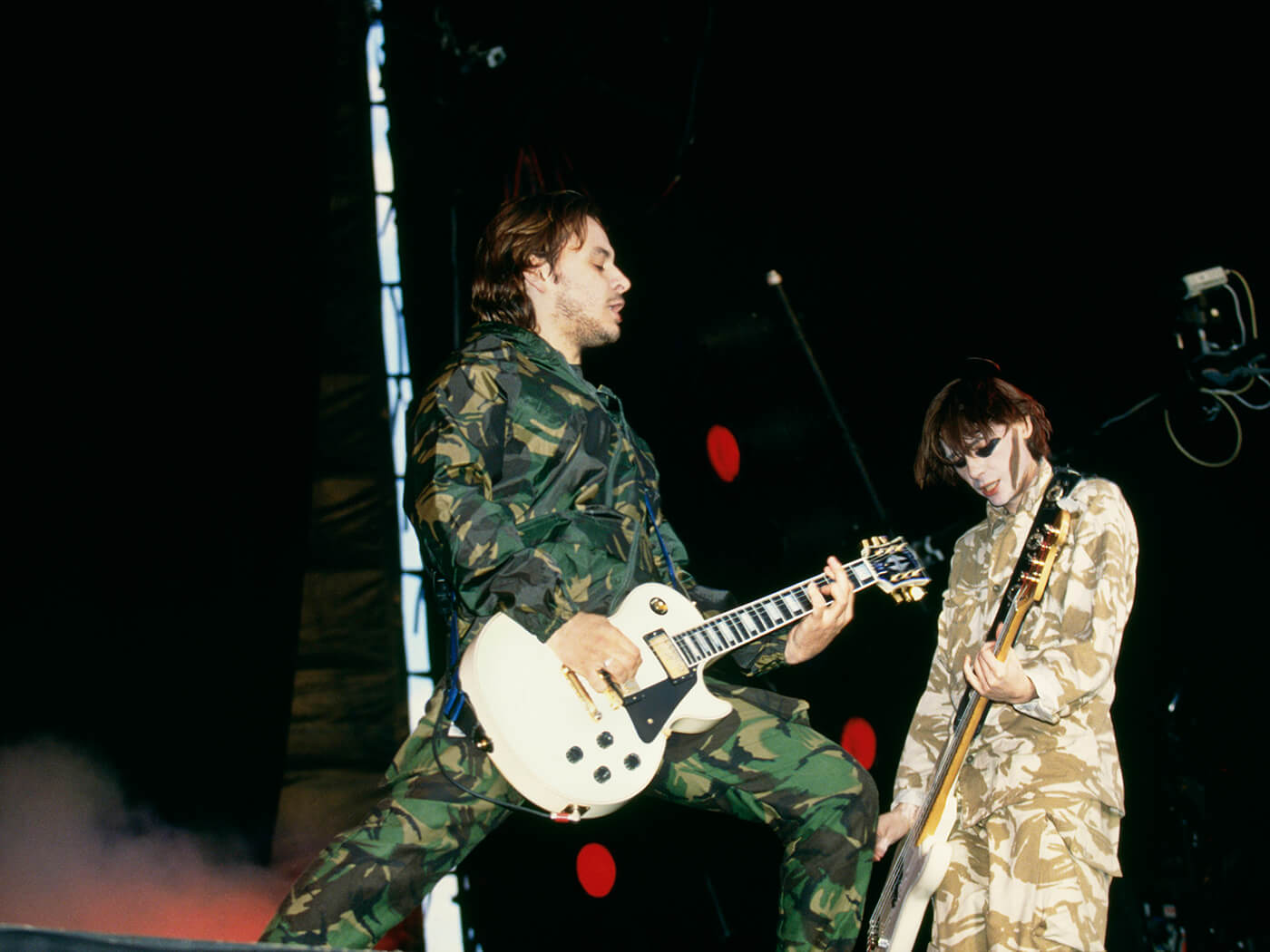

Though Edwards was its prime instigator, the collective agreement to pursue a darker direction had stemmed from a shared sense that the band was at an impasse, following the muted reception that met their previous record. “There was a realisation that we hadn’t got as big as we thought we would have.” Manics’ bassist and additional lyricist Nicky Wire reflected, back in a 2014 interview with NME, who also admitted that the switch was spurred by the band wanting to be ‘100 per cent truer to ourselves’. James Dean Bradfield, too was conscious of the band beginning to slide into a predictably ‘rockist’ niche.

In pursuit of this truer sound, the band resisted label pressure to record in a luxurious studio in sun-drenched Barbados and instead decamped to Cardiff’s minuscule Sound Space Studios. It was here the four set to work on concocting the more upfront sound which was more in-keeping with their formative influences, such as Joy Division, The Clash and Magazine.

Though friend and engineer Alex Silva was on hand to capture and engineer the four, no overall producer was designated. Silva told the R*E*P*E*A*T Fanzine that “I think at the time, the band had an ideal, James said that ‘No albums have been produced since Led Zeppelin III’. So in that case, they felt there was no need for a producer as such – maybe because the term ‘producer’ carried too much weight for them. I’m fine with my credit, I just recorded what was there.” Another guiding hand who would enter the frame later in the process came in the shape of mixer Mark Freeegard, who told the same fanzine that the recording choice to initially capture the album on 1-inch tape factored into the demo-like sound the band were striving for.

For The Holy Bible sessions, Bradfield minimised the number of guitars, and stuck largely to his trusty white Gibson Les Paul; a staple instrument that he’d purchased from a Denmark Street guitar shop back in the early 1990s. It’s a guitar that has appeared in some form on every MSP record. “It is my most valuable six-stringed friend” he lovingly expressed to Guitarist in 2014. Bradfield also used a buttercream Fender Jazzmaster for a handful of other songs, including the tonal switch of the glistening open-G-forged This Is Yesterday – a gorgeous composition that serves as the record’s brightest moment, a lone glimmer of candlelight in the stygian abyss.

James used both a Marshall amp through a 4×12 cab, as well as a Vox AC30 throughout the recording, with the occasional use of Soldano amp, output through the same Marshall cab. Though this was the core of the rigid and deliberately minimal set-up, Bradfield’s Fender Twin Reverb was occasionally wheeled into the studio to wrangle a few more interesting tones. Pedals were also kept at a relative minimum, though an unmistakable BOSS Hyper-Fuzz (rumoured to have actually been owned by Richey Edwards) is regularly deployed. A CH-1 Super Chorus (with a super fast oscillation) augments the sound of Faster’s opening squeal and is used in more slowly oscillated form for the racing barrage of Of Walking Abortion’s intro. Other effects were achieved with rack mounted units, such as the Marshall Time Modulator.

Though Edwards shaped the record from a conceptual standpoint, he never actually recorded any guitar parts himself, entrusting the more capable Bradfield to meticulously lay down each part. On the resulting tour however, Richey was known for sporting an elegant Thinline Fender Telecaster (later to be used by Bradfield) as well as his own Les Paul Standard.

I am an architect

Working from Edwards’ unstructured, essay-like lyrics, James assembled tight chord sequences, layered with turbulent eddies of noise, while also slotting Richey’s words into immaculate top-line melodies. It was a challenging, unconventional approach; “Some of the lyrics confused me. Some were voyeuristic and some were coming from personal experience. I remember getting the lyrics to [album opener] Yes and thinking ‘You crazy fucker, how do I write music for this?’” he recalled in the liner notes for the tenth anniversary edition of the record.

From the outset, Bradfield’s supreme gift for riff-craft is palpable. Propulsive opener Yes’s lead riff in E major manages to set both the jogging pace of the track, while also being spiky enough to mirror the bubbling paranoia of its lyric. As Bradfield fiercely delivers Edwards’ fractured observations on the parallels between prostitution and the broader notion that ‘everyone has a price’, this lasooing, spritely riff keeps the arrangement energetic, trickling out the scale’s notes rhythmically while a punctuated hammer on G♯ from F♯ contributes to a sense of unease. Jumping to a fuzzed-up, punkier tone for what is technically a pre-chorus (though in reality serves as the first of two different choruses for the song), the band ramp up the intensity with a sequence that switches to A major, before sliding back to E, a tonal switch of a C♯ and G♯, before a leap to a B major bridges us toward the chorus proper – a cacophonous, doom-laden ascent from E to C♯m, leading us to a wavering wobble over the precipice of a 7th position E5 power chord. It’s an exhilarating start that decrees the shifting violent sonic tone of the record.

The volatility is kept as the second track’s laddering 6-note riff jostles for attention, untangling itself to reveal the ferocious assault of Ifwhiteamericatoldthetruthforonedayit’sworldwouldfallapart. In lieu of a conventional chord sequence, Bradfield arpeggiates a deathly-sounding Cmaj7 shape, fretted down in the E note of the A string on the 7th fret. This macabre motif frames a venomously spat lyric, as Edwards’ words unpick the hollow fallacy of the exported American dream. A hard-lurch into a rhythmically double stopped E major chord ushers in what sounds like a cavalry charge, surging down a hill, as drummer Sean Moore thunders on his kit militaristically, and James swings between four valiant-sounding chords.

This newer, more intense, version of the Manics wasn’t just the result of stomping on a fuzz pedal and hammering out a salvo of power-chords, Bradfield’s writing on The Holy Bible is more carefully constructed than ever. The spindly, palm-muted arpeggios of She Is Suffering sounds like an inverse, gothic re-working of The Police’s Every Breath You Take while the perilous atmosphere of the tense Die In The Summertime finds Bradfield creatively playing off Edward’s lyric with a rigid two-note riff. “It’s quite a muso album” Bradfield claimed at the 2015 NME Awards, “It’s all very interlocked with each other – and it’s very fast.”

Even a close listen to the record’s punchy post-punk triumvirate of Revol, Faster and P.C.P affirms Bradfield’s commitment to housing and enhancing Edwards’ potent themes above all. Faster in particular is notable for its squalling high-oscillation Chorus pedal wail, as well as its thorny, push-and-shove verse part; both sections built from two wildly different, but complementary, variations of the same two notes (G♯ and A). The pulsing heartbeat of the verse part allows for the record’s most fluid stream-of-consciousness tirade. “I remember reading the first line of Faster – ‘I am an architect, they call me a butcher.’ – and I thought ‘Fucking hell, I can’t fuck this up, I’ve got to write some great music to this”, Remembered Bradfield, in Kevin Cummins’ Assassinated Beauty.

No birds

Interspersed throughout the record, are a series of – often chilling – spoken word audio samples (captured with Sean Moore’s newly purchased S1000 Akai) taken from a range of films, documentaries and interviews. These clips preface the thematic concerns of the songs-proper, such as the haunting clip of Irene MacDonald, the mother of Jayne MacDonald – a victim of atrocious serial killer Peter Sutcliffe – which prologues Edwards’ capital punishment-oriented Archives of Pain. This song proved to be a controversial one, with a seemingly pro-death penalty lyric that would perturb analysts for decades to come. Driven by Nicky Wire’s sludgy bass line, James sheds some high register rivulets of sound before snapping in line with Wire’s brutal riff-march. Haunting chorus-soaked arpeggios frame its chorus section, as Edwards’ most sinister lyrics yet are delivered. A fittingly odd arrangement for a particularly grim piece.

At its darkest, The Holy Bible underscores its writer’s unrelentingly bleak outlook on humanity, and the shape of the systems that govern it. It’s unquestionably a troubled mind that lay behind Of Walking Abortion’s indictment of humanity’s indifference to suffering, The Intense Humming of Evil’s fragments of barbarous holocaust imagery and Mausoleum’s black-skied, corpse-ridden landscape. But, it’s 4st 7lb where Edwards’ own personal pain reveals itself more candidly. The first song recorded for the album, this remorseless semi-self-portrait of a struggling anorexic, also illuminates his gift for poetic lyricism. For the track, Bradfield opted to set a tormented tone with an off-kilter, jittery riff, adrift amongst waves of feedback. The arrangement builds out with snaking fuzz riffs and staccato chord punctuation, as well as an ethereal, chorus-drenched second section, which features some harmonious Les Paul licks. It’s a painterly approach that wrings out every drop of the lyric’s underlying emotional heart.

In these plagued streets

Ever since its release on August 30th 1994, The Holy Bible has been held as the high watermark of the Manic Street Preachers’ recorded output. It was a plunge into the dark which ultimately proved greatly cathartic for many listeners, deeply securing the band in the hearts and minds of its fanbase.

As with Nirvana’s In Utero (released the same year) and Joy Divison’s Closer, it is routinely dissected by those looking for greater insight into the mental state of its lyricist, seeking deeper understanding of what happened next – the mystifying disappearance and assumed suicide of Richey Edwards, who was last seen on February 1st 1995.

Reflecting on the record’s twentieth anniversary, in an interview with NME, Nicky Wire said “On The Holy Bible I think [Richey] invented a new lyrical language, which wasn’t easy for James to fucking put music to!”, while Bradfield reflected that, in contrast to the album’s harrowing tone, the band had a good time making it; “We were all getting on really well. It felt like we were taking the band seriously again. It was like a big monolithic slab of stone had just planted itself in the middle of the band, and we just had to follow every route. It was a good feeling again. It kind of felt like a restart.”

Inevitably though, the grief that followed Edward’s disappearance, led James to pore over the making of their last work together, and Edwards’ increasingly self-destructive behaviour, such as his propensity to self-harm. “I think back to those times and I think, ‘Why didn’t we see the gathering storm,’ but we were still in thrall to the canon of visual work that Iggy Pop had done, and people like that. You know, we still felt as if we were part of rock’n’roll expressionism I suppose.” He said in Assassinated Beauty.

While the Manics strove on in the wake of Richey’s departure, filling out their discography with an extensive canon of records across the ensuing decades – including politically-charged infectious latest offering The Ultra Vivid Lament – the shadow of their third record hangs still looms over their legend.

Looking back at the NME Awards in 2015, James reflected; “It’s an album that represents a quite fraught, but quite happy time in our lives. We knew we were making something special. We felt we had nothing to lose. Richey wasn’t in such bad shape when we were actually making that record, it was the calm before the storm. Everything is indelibly etched in our hearts, in our minds, and in the music.”

Infobox

Manic Street Preachers, The Holy Bible (Epic Records, 1994)

Credits

- James Dean Bradfield – Guitars vocals

- Richey Edwards – Lyrics and concept, guitar, sleeve design, production

- Nicky Wire – Bass

- Sean Moore – Drums, sampling, production

- Alex Silva – Engineering

- Mark Freegard – Mixing

- Steve Brown – production on She Is Suffering

Standout guitar moment

Faster

For more reviews, click here.