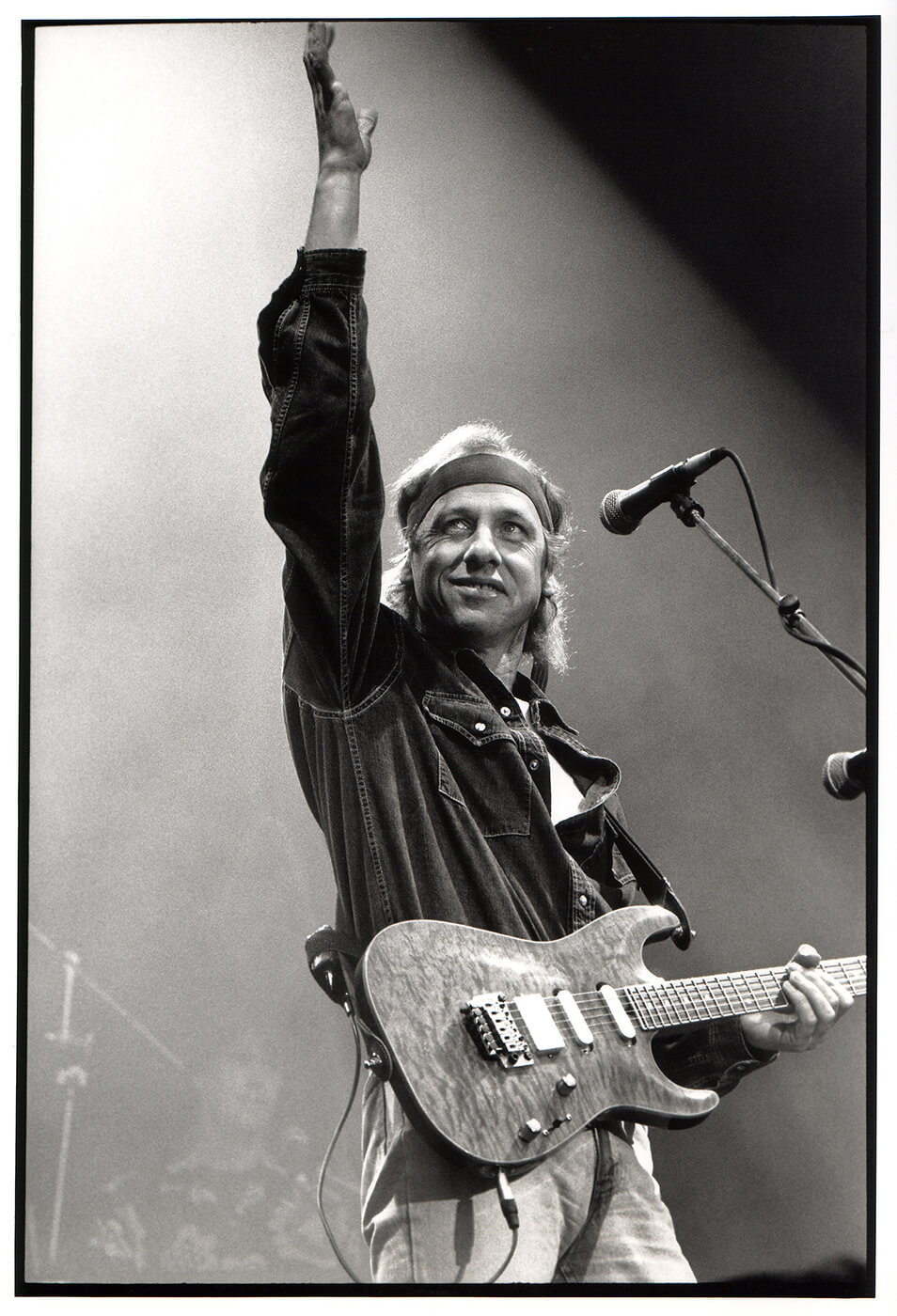

“Having good chops definitely helps, but it’s not the whole story”: Mark Knopfler on musicianship

Despite leading one of the world’s biggest bands, Mark Knopfler reckons he’s an underachiever. In this interview, the former Dire Straits man talks playing live, songwriting and collaborating with the legendary Chet Atkins.

Image: Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns

This interview was originally published in 1993.

“I remember sitting in a bar listening to Telegraph Road,” says Mark Knopfler, “and I thought to myself: ‘What a lifeless bunch of old toss this is!’” As a highly respected and successful musician, Knopfler is more entitled than most to heartily congratulate himself on his achievements. Perhaps surprisingly, he sees things very differently. As he sings

in On Every Street: “Every victory has a taste that’s bittersweet”.

“The jukebox played Rave On by Buddy Holly immediately afterwards,” he continues, “and to me, it just totally eclipsed Telegraph Road and blew it into the weeds. Now, that’s my kind of music! Rave On was bigger and better, even though there were only three instruments, and it was just bursting with life and joy. That was a real lesson to me and I think you can hear it on the last album.”

Having just returned to London from Dire Straits’ massive world tour, Mark happily reports that: “It was a lot better organised than the Brothers In Arms tour. We had plenty of time off in between legs and we tried to change things around a bit by playing different songs on different nights. In Europe in particular, we’ve had some really good crowds which take the gig to a higher level. I think we started playing better as the tour progressed, but the thing you have to watch on a long tour is overplaying. I found on the Brothers In Arms tour that people find spaces to fill in the music and when you listen back to it, you find everyone is doing too much. This time, we were watching out for it and as a result, it didn’t really happen. I really don’t know about whether or not you could say we have ‘magical nights’ when everything just effortlessly falls into place, but I would say that certain songs suit certain players better than others.

“I don’t know how often that kind of ‘transcending’ gig is supposed to happen – if I’m finding my way across the fretboard well and if I’m getting a sound I like, then sure, things can definitely take off.”

The band’s too strong

Never a band for grand gestures or the massive stage shows popular with what he calls the ‘jackboot’ rock bands, Mark prefers to keep the occasion of a Dire Straits gig relatively low key.

“You have to hold back and avoid letting things get out of hand, but at the same time if you’re playing a bigger place, you’ve just got to project yourselves a little more. It’s not something we’ve pursued as a science – I think you just grow into doing big shows from playing them again and again. When I was a kid, the City Hall in Newcastle seemed a pretty big place, but walking into it now, it’s almost like a front room or my manager’s office. One of the enjoyable things about rehearsing is you can find things to do differently from the album version – this band was flexible enough to do all sorts of things. Sometimes, if the arrangement on an album is alright, we’d pretty much stick to it. But generally speaking, on this tour we changed things about quite a lot, even Sultans….

“There were a lot of us onstage and the interplay between everyone increased as the tour went on – first, you find things to play off each other in rehearsal, then you find more and more as the tour progresses and the song takes its shape. People find their own parts better or find variations, and the thing develops into something else. We didn’t really have a single musical leader onstage. Sometimes, you have to take a groove from a drummer, but on other things, the rhythm section has to follow the guitar.

“On something like Heavy Fuel, you just go with the drum beat, whereas on something with an R&B feel like Two Young Lovers, the rhythm section has to tuck in behind the guitars – two opposite situations. Compared to all the bands that I’ve played in, whether it’s my early bands or Dire Straits or other people’s bands, I would say this line-up was actually the loudest band I’ve played in. That can be difficult for the sound people because of leakage, but I like a fair bit of level onstage. If you’re too careful about stage levels, then you lose a little grease – you’ve got to know that there’s a rock band playing there.

“Terry Williams was the loudest drummer the stage crew had heard in terms of decibel levels, but Chris Whitten was hitting them even harder, going through drum heads like there was no tomorrow. Also, the way the stage was built, with Chris quite high up and back, made him hit the drums even harder than he normally would!

“Peoples’ monitors were pretty damn loud as well. You’d walk up to someone else’s monitor and go: ‘My God, what’s this?’, and a couple of the guys in the band have experimented with earplugs. “If you’re a keyboard player in the middle of a racket like that with a hard-hitting drummer behind you, a great big beefy percussionist behind you, three guitar players wanging away in front and you’re standing on top of the guitar players’ cabinets, which are forming your floor… Well, you’re going to need a fair bit of level just to be able to hear what you’re doing yourself. It took a while to get that sorted out, but we got there in the end. We had a phenomenal sound crew who’ve got a real reputation for getting things sorted out. Basically, we just dump the sound problems in their lap and they sort things out – we didn’t even have to do soundchecks every night. If we were going to be playing several nights in a particularly difficult hall then we would do a soundcheck, but otherwise, we didn’t, even with a nine-piece band using lots of different instruments – Paul Franklin played three different kinds of steel guitar, Chris White played three or four different kinds of saxophone and percussion. Phil Palmer used a handful of guitars and so did I – so there was a lot of stuff to check! Plus, we had five people singing.”

Setting me up

“I always start with kick, snare and hi-hat in my monitors, with the hi-hat a bit louder than you would hear it in a normal mix – so that if I’m playing 16th notes, I can tuck in to the beat. I used to try to make sure everyone got the hi-hat, especially for fast rhythmic playing when it helps to keep things together. On this tour, there was always stacks of rhythm because Danny on percussion was helping Chris with the groove, so there would be a mighty shaker there, or something else that would keep you grooving.

“You’ve got to be really careful that you don’t cloud your monitors with far too much – I did want to have an overall mix of the band, but it ends up being a little bit tricky – sometimes it’s best just to use someone’s stage level for monitoring. After a while, your monitor man gets used to what every single person needs for every single song – which is a hell of a lot of combinations! Obviously, if you can’t hear all the background vocals perfectly, you can’t complain – you’ve got to be practical. As long as you’ve got the basics there and are able to play in time, then you’re three-quarters of the way there.

“Songs always change as you gig them, especially at first. When we did the first Dire Straits album, we’d rehearsed hard and gigged hard, so we just had to go into the studio, set the equipment up and play. Brothers In Arms and On Every Street would sound very different if we had gigged the songs first. “Actually, I don’t think any of the Dire Straits albums are all that good. On Every Street is the best in a lot of ways, ’cause a lot of the stuff was recorded with everyone playing together. We also had the time to get to know the songs better and do a bit of work on sounds and arrangements. But I certainly don’t enjoy listening to stuff that I’ve done in the past. It makes me very uncomfortable.”

Although Mark’s often accused of playing safe, this criticism can hardly apply to some of his more epic songs, such as Private Investigations and that ‘lifeless bunch of old toss’, Telegraph Road.

“Yeah, I guess I was experimenting with form and length on those songs. We still play them onstage, but I certainly wouldn’t do anything like that now – I don’t write stuff like that any more. My favourite music is simple, basic, straightforward music – little songs, if you like – so I really don’t know how I found myself doing all that stuff! I’m credited with producing Love Over Gold, but ‘producer’ is a very loose term. Sometimes, a band will be producing themselves, even though there is someone else’s name on it.

“The term is flexible and depends on who is recording – sometimes, producers just direct traffic and other times, it’s an administrative role of signing session players’ forms. Usually, I’d think it’s a cooperation between the artist and the producer – the producer brings an outside mind to the record.”

Hit business

Around about the same time, when Mark was ‘producing’ Love Over Gold, came a more demanding challenge – writing his first soundtrack, for Local Hero. “It has probably been the most successful sound in terms of sales, but I’d say none of them have been much good, really,” he reflects. “It’s a horrible business – I think they should have hired someone who can do the job properly. When I’m doing soundtracks, I think I just stagger from one crisis to the next! It’s quite different from songwriting and requires a lot more discipline, which I just don’t have.”

Known for his silky Strat tone, Mark notably departed from his trademark sound for Money For Nothing from Brothers In Arms.

“I was using my Les Paul through a wah-wah pedal and I set the pedal at a certain point which got that particular tone. My co-producer and engineer, Neil Dorfsman, put some fancy little effect on it as well, but the sound was basically coming from the pedal being set in one place.

“I couldn’t remember how to do it later – when I had to recreate it for Weird Al’s spoof version, I just couldn’t get the sound. Guy Fletcher remembered that it was through a pedal and then it all came together – we had the Marshall all cranked up, but couldn’t get the tone until I used the wah-wah.”

As a producer in his own right, Mark has definite ideas about how musicians ought to work in the studio. “I think the thing that’s wrong with modern recording is that the musician is very often robbed of his right to play with other musicians. Very often, people will find themselves overdubbing on tracks made by people they haven’t even met!

“Something happens to the air when you are all playing together, and multitrack recording hadn’t been around for very long before musicians started being stuck in isolation booths and there was no spill – leakage and spill are obviously a total nightmare for engineers, but I love it. When you find yourself in the professional recording process, you take onboard all the stuff that engineers and producers do and it’s not always for the best.

“If you’ve got a suitable studio and a band that’s good enough, then I think it’s a good idea to record things together, so you can play off each other. The recording process encourages you to go for perfect performances each time, but mistakes on record start to sound good after a while. There are piles of mistakes on Dire Straits’ records… but probably not enough! I could point out mistakes in just about everything.”

Chet lucky

“When I started working with Chet Atkins on the Neck And Neck album, again, we were working on a limited budget – I refused payment for the album, but I think in the end, we split the royalty in half. When I first went over to work with Chet, he had a bunch of guitarists come in from all over the world – I think I was the only Englishman. I had made enough money from music and I knew Chet didn’t have the finances to pay huge great session fees. I was just happy to be asked and, in the end, we ended up doing a record together. Again, it was a home-studio thing recorded at Chet’s place and we only spent a couple of days in a ‘proper’ studio.

“Working with Chet and other fine musicians like him really helped my playing – you’re always learning when you play with good musicians. I like the idea of change – I don’t want to stay static. I like the way I play in my heart and I wouldn’t want to be anyone else, but I’m conscious that there’s a whole world of playing out there that I don’t do – it’s bottomless, really.

Left over right

“If I get a book out, I’ll find something and make it my own – either by adding my own style, or because I couldn’t play it properly in the first place! I’m left-handed, but I play right-handed. They tried to teach me violin at school for two or three years – right-handed – so by the time I was 15, I was into the habit of playing that way round. It has some advantages – it obviously means my strong hand is on the neck for a good vibrato. I can pull or bend three strings all at the same time quite easily. When I was learning the guitar, I used to play with a pick a lot – a pick is the biggest amplifier there is and not using a pick is the main difference in my style.

“When the fingerpicking style and flatpick style were fusing together for me, I realised I was doing things with my fingers that I used to do with a pick, but it was more comfortable and more rhythmic with my fingers. This was well before Dire Straits – I remember being conscious of the style developing when I was sleeping on someone’s floor in Turnpike Lane. They had a cheap copy of a Gibson Dove acoustic with very light strings and I realised the pick was becoming redundant.

“I don’t play all that much on the road, apart from the gigs. In-between tours, I get the chance to sit down and play a bit – I intend to work out more of a structured routine. I spent some time a few years ago getting some books out and studying a bit, because I was being asked to play sessions with proper musicians.

The solo voice

“When I’m working on a solo, I don’t really know how it comes about. I think not being able to sing means the guitar becomes like a voice and you make it do things that you wouldn’t do otherwise. Perhaps if you can’t sing, you push a little harder with your instrument, but I’ve never really thought about that. There are lots of guitarists and musicians with tremendous facility, but they might not be musicians to me – ‘musician’ is a difficult term. There’s a lot more to it than just technique.

“Van Morrison has great facility with his voice, but not the same facility with piano or guitar – but that doesn’t matter. He understands what music is and his roots go very deep into Celtic music and the blues. He’s capable of great moments of fusion of the two – that’s something that has little to do with facility or book knowledge. Having good chops definitely helps, but it’s not the whole story.”

Country influence

“I think kids learning from transcription books is fine, but I think the best way to learn music is from lots and lots of old records. It helps when you’re learning something new to have some sort of feel for what has come before. BB King wouldn’t play the way he played unless he’d heard Lonnie Johnson.

“As soon as you play with Chet, you realise you might as well forget trying to do Chet’s thing, so I didn’t have to practise especially for it – I just tried to be myself. Playing with Chet was a tremendous privilege, because you can steal things and make them your own. There’s a little lick on When It Comes To You that I stole from him – we were playing around in open tuning one day and he played this great lick. He showed me it and I stuck it right into that song. One of the great things about Chet is he’s got piles of these little licks. If you’re recording with him, I would just wait around until he came up with something and then learn it from him.

“I’ve always listened to country music and I’ve been going to Nashville for years – that influence has come out more on the last album. They’ve recorded a lot of my stuff in Nashville and it’s come to be more and more over the years. I’ve always loved country and blues and I guess I was listening to a lot of that around about the time of On Every Street – it just seemed such a relief from all the other crap that was being made at the time.”

A man who clearly loves his job, Mark is no sooner off the road than he’s back into the studio again – but some projects are apparently more enjoyable than others. “I’ve just started doing the next live Dire Straits album and I’m actually bored out of my mind already. It’s just basically listening to the same songs over and over trying to choose the best performances. It’s miserable – I can’t wait to finish it and do something else!”

For more interviews, click here.