How Kevin Shields and My Bloody Valentine changed the course of guitar playing forever

Back in the late 80s, My Bloody Valentine revolutionised many players’ ideas of what a guitar sounded like. It was a mix of borrowed gear, happy accidents and “sound as an infinite horizon”… and still sounds awesome.

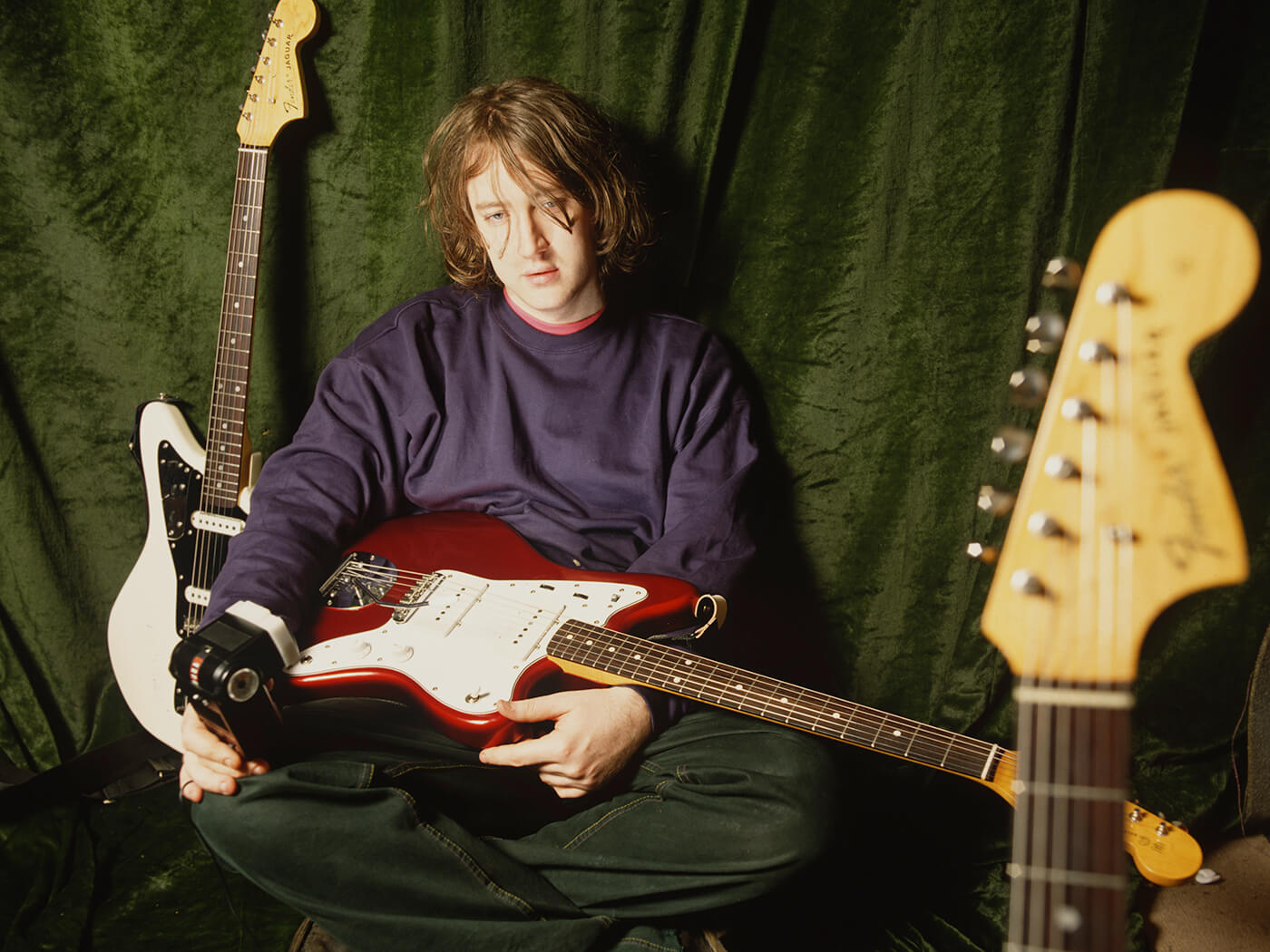

Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine. Image: Larry Busacca / Getty Images

So, My Bloody Valentine records are available on streaming services, finally. And more dramatically, they’ve signed a new recording deal. For streaming customers, it’s a chance to finally hear a band still talked of as ‘legendary’ and ‘revolutionary’ by many guitarists… albeit likely at a 44.1Hz sample rate that recording perfectionist and leader Kevin Shields never, ever intended. Still, that’s progress… apparently.

The new recording deal, with Domino records, is the ultimate end game and the biggest news of all. In an existence (you can’t really call it a ‘career’) that now spans 38 years, My Bloody Valentine have set new levels of unproductivity. Yes, they released a ‘no fanfare’ album in 2013, simply called m b v, but before then you had to go back to Isn’t Anything (1988) and Loveless (1991) for their only two LP releases. MBV make The Stone Roses look like workaholics… and we all know how the Mancunians’ much-heralded 21st century comeback fared. Should people really care, then, about My Bloody Valentine when it could all be so similar? Well, Shields this time seems driven: the past catalogue streaming will be followed by analogue vinyl reissues and plans for two new albums…

The sound of the new

I once had an argument with Billy Corgan about My Bloody Valentine. Well, kinda. I was in Germany for Guitar Magazine as the Pumpkins toured their grand Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness double album around the globe. That was an album that had rocketed way beyond the supposed grunge roots of the Pumpkins sound, and to devastatingly impressive effect, so I asked Corgan about the breadth of influences at play. Billy wasn’t having any of it.

“Oh, gaaaahd…” he drawled disapprovingly. I paraphrase, but his full reply went something like. “You wouldn’t be surprised, honestly. By any of it. Sabbath. Led Zeppelin, Rush. Van Halen,” he reeled off, clearly not thinking of his answers. “Everything obvious. You can hear it all on the records. We’re playing great right now, but please don’t expect me to claim I’m coming up with something new. I’m really not.”

He fixed me with the eye of a lecturer. “The only player doing anything new on the guitar right now is Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine. Go and ask him your questions.”

It was possibly a stupid question on my part, but was Billy Corgan right? He probably was. Exhilarating though the grunge scene was, it clearly drew on much of what came before. There was a good reason why Nirvana had a track called Aero Zeppelin, right? In the UK, the Madchester bands were a hotch-potch of things: Happy Mondays’ biggest hit, Step On, was a cover of a 1971 hippie anthem. The Stone Roses oiled pretty classic Byrdsian 60s jangle pop with some E-dance lubrication, then went all Led Zeppelin, for The Second Coming, but that’s another second-hand story…

My Bloody Valentine were undoubted monarchs of the media-coined shoegazing scene, but they even transcended that, in truth, while also supposedly inventing it. The other big shoegaze acts – Ride, Lush, Slowdive – really were mostly about the pedals. The post-MBV bands’ new guitar textures – sometimes gauzy, other times ultra-heavy – did sound great, but were often applied from the top down, waves of wobble and fuzz on top of songs you could – at a push – strum on an acoustic guitar.

My Bloody Valentine were different to that. Theirs was a sound that applied from the bottom up. The sound was as much about how they played than what they played through. Even so, the sound of My Bloody Valentine was still one unquestionably founded on guitar hardware.

London calling

My Bloody Valentine dated back to 1983 in Dublin. Kevin Shields was born in New York, but had moved back to the Republic with his Irish parents aged 10. He befriended future MBV drummer Colm Ó Cíosóig around the age of 12, and together they indulged their love of punk and post-punk (particularly Siouxsie And The Banshees, Joy Division and The Birthday Party) as they found their creative feet. In 1985, a debut mini-album, This Is Your Bloody Valentine, came out but is for completists only. It’s typical mid-80s gothy indie, with a long-forgotten male singer.

My Bloody Valentine properly took shape when Shields and Ó Cíosóig moved to London, recruiting bassist Debbie Googe in 1985 and, crucially in 1987, guitarist/vocalist Bilinda Butcher.

It may be a surprise, but Shields at first saw Butcher as the more adept player; she had even played classical guitar as a child. In an interview with Guitar Magazine back in 1992, Shields remembered, “The reason we got Bilinda in was that she understood the rhythmic side to playing in a band. You’d play something and she’d play in time and with a sense of how it should all fit together. That’s rare. We may not have been technically very good, but I knew we had the right feel. When I started out I couldn’t play either. I never really had any interest in the guitar. I thought if I was going to do anything I might play a little bass just because it looked easy.”

Shields had his own disastrous apprenticeship on the guitar, which may have fuelled his later rule-breaking. “I got taught to tune the guitars using the 5th fret guitar-in-tune-with-itself method. I didn’t realise that you had to switch to the 4th fret for the G string. Everything we (first) did was totally out of tune because I was playing barre chords and sounding that totally out of tune string all the time! The tapes are very funny.

“To give you an idea, if anyone came in and asked me to play a scale I couldn’t do it. I don’t know the first things about any of the theory, but then you don’t make good music by following some old-time chord book. Things have changed.”

Not that Butcher should be misconstrued as having a scholarly “classical background” or anything lofty compared to Shields. She told Guitar Magazine, “When I joined the band, I couldn’t even play a chord. Kevin just said ‘Right, play those two strings in this order’, and he’d play something and I’d follow.”

But Butcher was much more than just a more studious guitar foil for Shields: indeed, on recordings she usually didn’t play guitar at all as Shields was conceptualising all the parts he’d play as he wrote. But in most ways, her floating vocals became the sound of MBV as much as Shields’ floating guitars.

On both Isn’t Anything and Loveless, Butcher was woken up to record her vocals to make them “more dreamy and sleepy” or “sensual”. Many bands might record in the morning because they’ve been cranking amps all night. For Butcher, “It’s 7:30 in the morning; I’ve usually just fallen asleep and have to be woken up to sing… I’m usually trying to remember what I’ve been dreaming about when I’m singing.” And sometimes that was improvised itself. Shields’ song demos sometimes contained vocal sounds and melodies but not actual words, so it was down to Butcher to meld them into coherence. Of sorts. Song design, from the ground up.

The MBV guitar manual: fully realised

When they met, Shields and Butcher both loved The Jesus And Mary Chain (the two acts would tour later together as part of the UK’s Rollercoaster tour package in 1992) and a ‘noise rock’ aesthetic was at MBV’s core. Perhaps tellingly, both Shields and Butcher went in to develop tinnitus… though they blame headphones rather than bone-rattling gig volumes.

Strawberry Wine (a single) and mini-LP Ecstasy were limited-edition releases that debuted the new line-up, but the jangling guitars and overlayered noise reflected their debt to the JAMC and other indie bands of the day. Close, but no cigar. The roar came with the next EP.

The five-track EP You Made Me Realise (1988) was their first release for Creation. Pete Kember, then of psychedelicists Spacemen 3, recalled seeing MBV play You Made Me Realise (title track) live in Northampton in 1988, after the quartet had supported the Pixies on the latter’s first European tour. “They’d transformed,” Kember remembered. “I don’t know quite what had happened, but sometimes bands hit a certain quantum shift. The noise was overwhelming.”.

Kevin Shields acknowledges that Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore and Dinosaur Jr’s J Mascis were increasingly influential on his guitar playing, but the real shift was technical: his use of reverse reverb. He explained how he’d used it on the Strawberry Wine and Ecstasy EPS, but “to no great consequence, because I was using it the way it was meant to be used. Then in ’88, I discovered that it was extremely sensitive to velocity and how high you hit the string. You could make huge waves of sound by hitting it softer or harder.” Before long, Shield’s use of reverse reverb essentially became a compositional tool. Again, song design from the ground up.

Back in 1992, Shields told Guitar Magazine his approach was “painstaking. We’re not geared up to being technically very proficient, we just try to do things individually. We haven’t tried to write songs for a while now. It’s no longer just a verse-chorus thing for us.”

The volume plus the reverse reverb meant MBV melodies were increasingly “hidden” in a wash of sound. And the third component in the sound was their discovery of Fender Jazzmasters and Jaguars.

“It moved us into another dimension really. We didn’t have a trem arm until the You Made Me Realise EP,” said Shields. “A friend of mine lent me his Jazzmaster and I started using it, initially to simulate bending notes.” The first song recorded was Thorn, on this borrowed ’64 Jazzmaster with the vibe arm set unusually high. “It occurred that you could play chords and use the trem arm at the same time – because the arm was so long – and get this amazing sound that wasn’t like string bending but was much better, sort of chord bending.” The more trademark Slow followed within hours, using the reverse reverb: “I’d never known a guitar that could sound like that.”

The live noise coda of You Made Me Realise itself became the sign off at their blisteringly loud shows. In the 2014 ‘shoegaze’ documentary Beautiful Noise, Billy Corgan (still a fan!), recalled the track played live by MBV on their 2009 reunion tour:

“It’s one of those things where, it was full volume and for the first three minutes it’s like; ‘Oh, okay this is kind of cool’. Then you’re like; ‘This is really too much, I wish they’d fucking stop’. And then at about seven minutes it actually became kind of funny. And about 10 minutes in you start actually getting into it.”

Another EP, led by Feed Me With Your Kiss (1988), largely revisited the gothy scuzz rock sounds of before, but Shields’ new-found way of writing and playing was all leading into full debut album Isn’t Everything, of November 1988. The new style became known as ‘glide guitar’.

One thing Shields didn’t like was the notion that MBV records were all the result of a mass of pedals. Sure, a Yamaha SPX90 (occasionally an Alesis Midiverb) offered up the reverse reverb and other studio effects, but the guitarist insists a lot of the basic sounds are simple.

“People make this mistake by thinking we use lots of effects to get our sound. They’re always asking what rack we use or whatever. That sound is purely physical. It’s a movement, a manual moving of the strings. The short travel of the Jazzmaster and Jag trem that gives it that characteristic sort of upwards drone to the chord. We never pull the trem up, just gently ease it downwards so you get this drifting upwards until finally the thing’s in tune.” The “effects”, added Butcher, are “just Kevin strumming but with his trem bar in his hand the whole time. A hazy feel, sort of hypnotic and free moving.”

Shields saying that “90 per cent of what we do is just a guitar straight into an amp” is something of an over-simplification, though. The “elephant, shimmering bit” of Only Shallow was, for example, ��“two amps facing each other, with tremolo. And the tremolo on each amp is set to a different rate. There’s a mic between the two amps. I did a couple of overdubs of that, then I reversed it and played it backwards into a sampler. I put them on top of each other so they kind of merged in.” Guitar stomps may not have been common, but Shields’ was essentially playing the studio. Sometimes, the dry amp signal isn’t used at all; just the post reverse-reverb signal.

And the woozy sound-assault meant any tuning oddities of Jazzmasters and Jags was rarely an issue. “If you set ’em up right, the Jazz and Jag terms are really reliable,” Shields said. “They feel tight, although we have a little give in the actual arm so it can be used while you’re playing really easy. I make sure all the bridges on our guitars are really rough so they catch the strings as the trem moves.

“That, along with the reverse reverb thing was ours, we defined it. The term’s not an effect, its an emotional thing and using it’s as important as what strings or what chords we play. It’s part of the whole feeling, the essence of the song.”

To add to the idiosyncrasy, Shields invents his own tunings (DAAAAD, anyone?) specific to songs. So, live, has a separate Jazzmaster stage-ready for each song. He’s dyslexic as well, which means he didn’t always make a proper notation of what the original tuning even was…

The longest comeback

With much of m b v being based on tracks cut in the early 90s, two albums of genuinely new My Bloody Valentine material would be a hell of a comeback. Will Shields rely on his old 1980s 16-bit lo-res reverb racks? Will ‘glide guitar’ v2 be powered by the vast steps forward in technology that have occurred since? Who knows. The irony is that the MBV sound is now all possible via a few choice reverb stompboxes… as Shields uses live.

Only one thing is worth a bet. If MBV’s comeback music does remind you of more recent guitar innovators… it’s probably of the bands who copied MBV in the first place.

For more features, click here.