Related Tags

The Genius Of… Icon by Paradise Lost

On their fourth album, Paradise Lost finished shedding their death metal skin and made a primal, existential masterpiece that should have been lauded by the ’90s mainstream

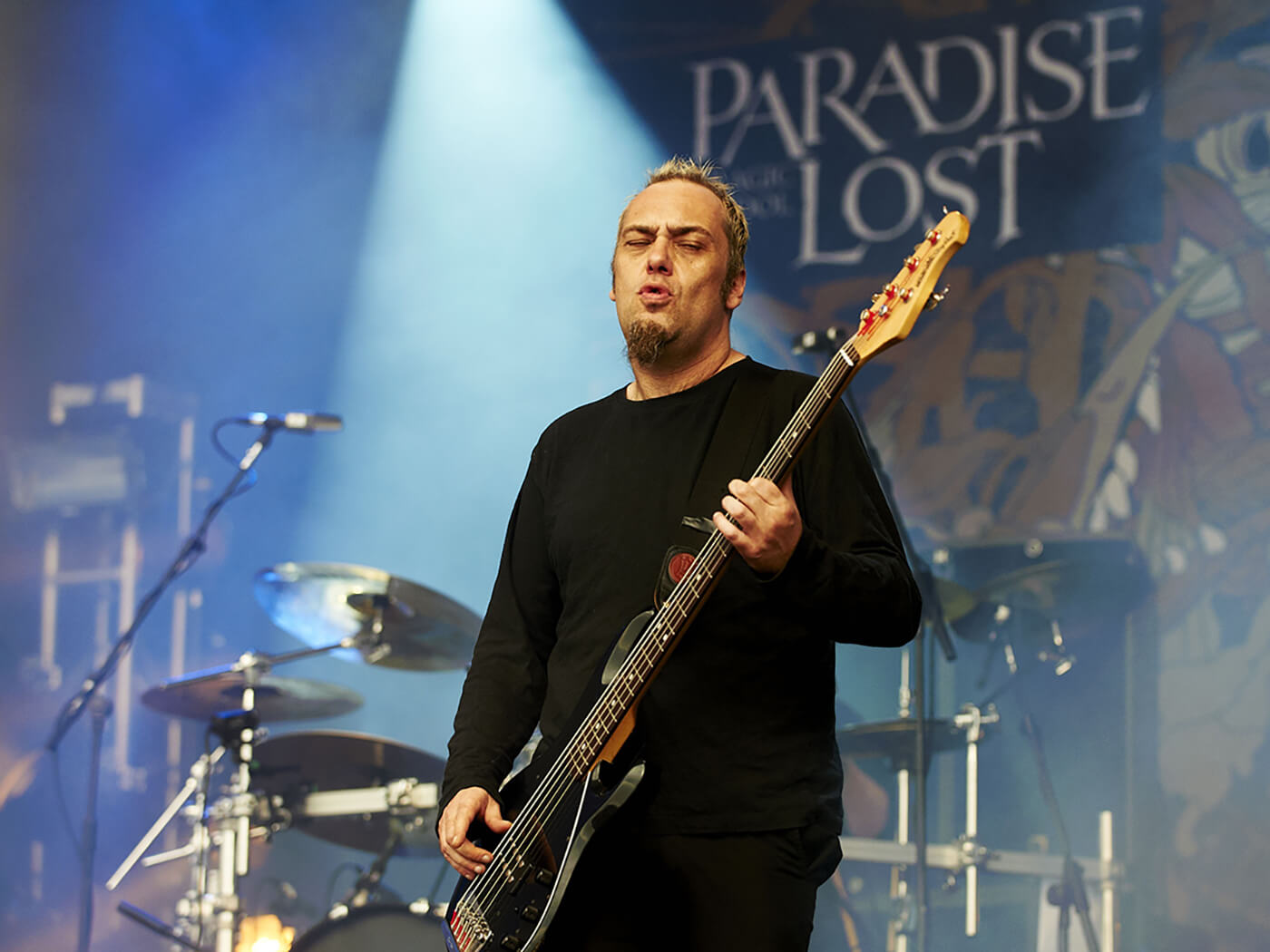

Paradise Lost in 1993. Image: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

There was a six-week span in 1991 that rewrote the entire heavy music rulebook for the decade to come. On 12th August that year, Metallica released their landmark Black Album and immediately reset the commercial parameters for metal. Then, on 24th September, Nirvana’s Nevermind came out, its accessible angst making sadness – not anger or bravado – the new must-hear emotion in American alternative music.

- READ MORE: Nirvana’s 10 greatest guitar moments, ranked

The impact of this one-two punch made the States’ hard rock mainstream shit itself. Bands who ranged from Pantera to Korn were all thrust into prominence as corporate suits scrambled for the next big thing to lead the way in a new landscape. Little did any of them know that they could have found it if they just cast their ears towards the pokey town of Halifax, Yorkshire, and a band called Paradise Lost.

Released in 1993, these Northerners’ fourth album, Icon, should have been a generation-defining chart-topper that affirmed the new direction of heavy music. Its rhythms are as forceful and simple as the Black Album’s, its mood’s defeated and depressive, and its lyrics are cryptic, existential poetry comparable to Nirvana’s. That combination struck European audiences enough to make the album an underground classic, even as it nears its 30th anniversary – however, behind-the-scenes bullshit denied Paradise Lost their deserved mainstream recognition as the visionaries they were and still are.

Revisiting Icon in 2023, it’s crushing that the album didn’t set the heavy metal world afire. Composer and guitarist Greg Mackintosh sought to make a “churchy”-sounding record (as would be befitting of the title), and the result is both sluggish and epic. Single and standout song True Belief blows the fucking doors down when it opens with crashing guitar chords, the slow snares behind them emulating the rhythm of cathedral bells. Greg and co-player Aaron Aedy play the muckiest of rising melodies, then singer Nick Holmes – despite his aggressive, James-Hetfieldian bark – roars a hook that’s nihilistic and introverted: “All I want is the same. All I want is a true belief.”

The rest of the album is a masterclass in marrying adrenaline to sorrow. On Widow, Greg plays a morose melody on top of a galloping, Iron Maiden-like beat from drummer Matthew Archer. Stephen Edmondson’s pensive goth bassline on Colossal Rains is gradually joined by a gritty guitar line and metallic howls, while Embers Fire follows sullen strings with a nosedive into grooving heavy metal and a moody rock chorus.

In the British press, the release of Icon was followed by a new subgenre tag: goth metal. Paradise Lost have always sourced influence from goth rock bands, especially the Sisters of Mercy, and the album frequently hits like Fields of the Nephilim have dropped a bollock. Joys of the Emptiness has a pre-chorus built out of moody guitar arpeggios that Killing Joke would relish, before it rises into a refrain of roars and Van Halen-ish tapping.

Icon practically demanded a new descriptor, since its sound demonstrated Paradise Lost finally fully shedding their old one. The band emerged as one of what is now known as “the Peaceville three”: a trio of Northern bands (rounded out by My Dying Bride and Anathema) on Peaceville Records who in 1990 made death metal slower and sadder. It was the nucleus of what became the death-doom subgenre, but Paradise Lost rapidly telegraphed they weren’t going to be content simply aping Bolt Thrower at half-speed.

The band’s ensuing two albums, 1991’s Gothic and 1992’s Shades of God, gradually integrated more prominent goth cues into their snarling metal. Strings, operatic backing vocals and acoustic guitars crept in, before becoming overt on the latter album’s closing track: the tense yet catchy As I Die. Combined with the fact that Nick was gradually ditching death metal vocals out of boredom, it was a signal of an impending sea change in the Paradise Lost sound. Whatever was to come next would be a dramatic statement.

With Shades of God came teases of mainstream recognition. Paradise Lost were profiled on MTV’s Headbangers Ball in 1992 and graduated from Peaceville to Music for Nations. On the surface, it seems like a shrewd business move. After all, look at Music for Nations’ Wikipedia and it’ll tell you that it released albums by Metallica, Slayer, Anthrax, Testament, Exodus – a who’s who of stateside ’80s metal.

The caveat, though, is that Music for Nations was merely the European distributor for those bands. It had next to no power in the States – and chart figures for releases where it was the sole label involved, like Opeth’s Blackwater Park and Cradle of Filth’s Dusk and Her Embrace, prove it. As a result, Paradise Lost were denied their deserved celebration as the band playing both the primal metal and emotional sensitivity that the mainstream wanted in its alt-music back then.

30 years on, Paradise Lost are still as restless as they were in the lead-up to Icon. They followed the album with the even more accessible rock stylings of Draconian Times and One Second, and are today in an intriguing halfway house where they mix anthemic gothica with the odd death metal explosion from their earliest days. Even though they found a modicum of chart success towards the mid-to-late ’90s, when you’re a band this ingenious and evolutionary, that still means you’re underrated.

A 30th-anniversary re-recording of Icon, Icon 30, comes out on 1st December. Paradise Lost will play the album in full on a European tour later that month.