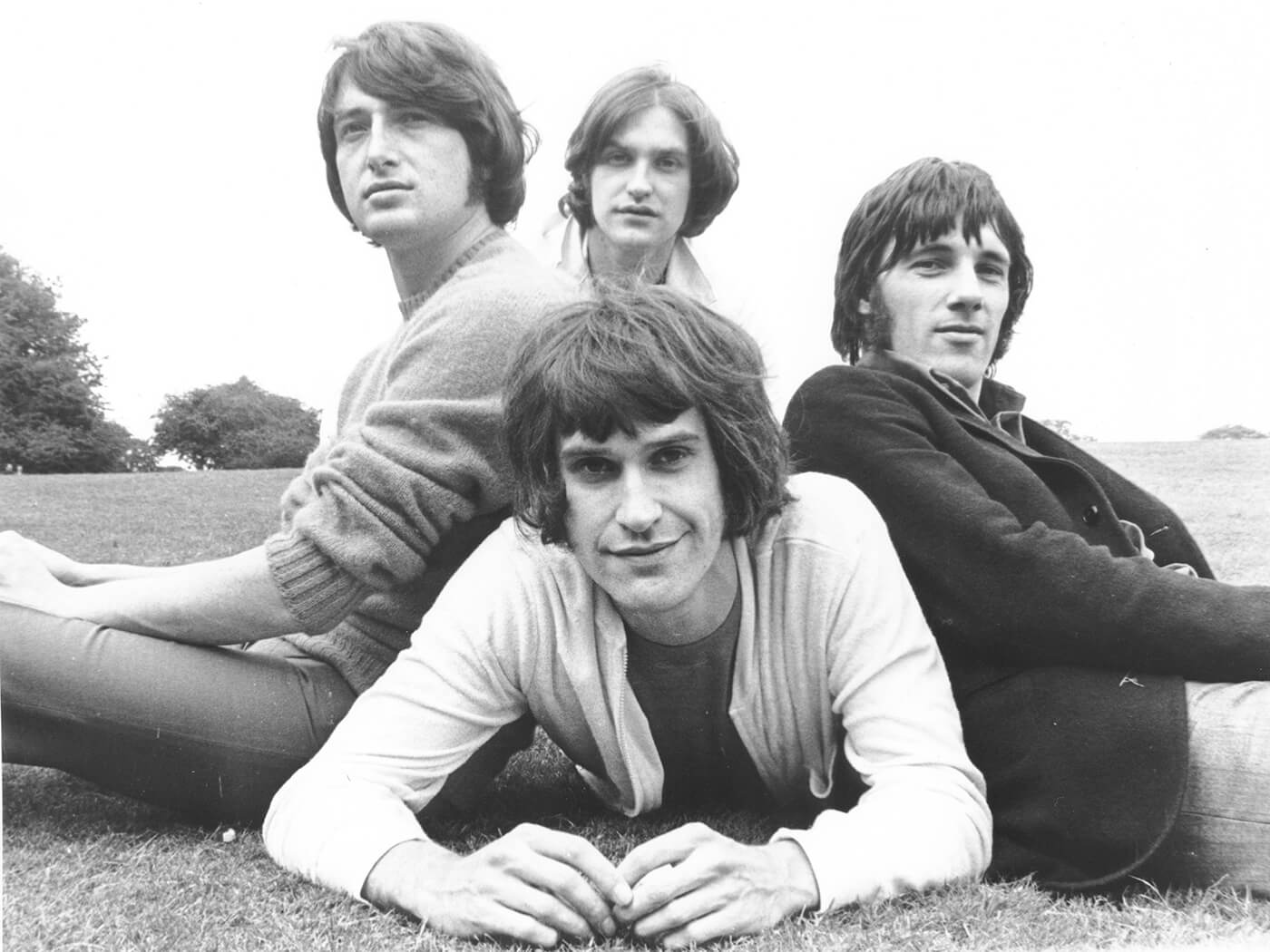

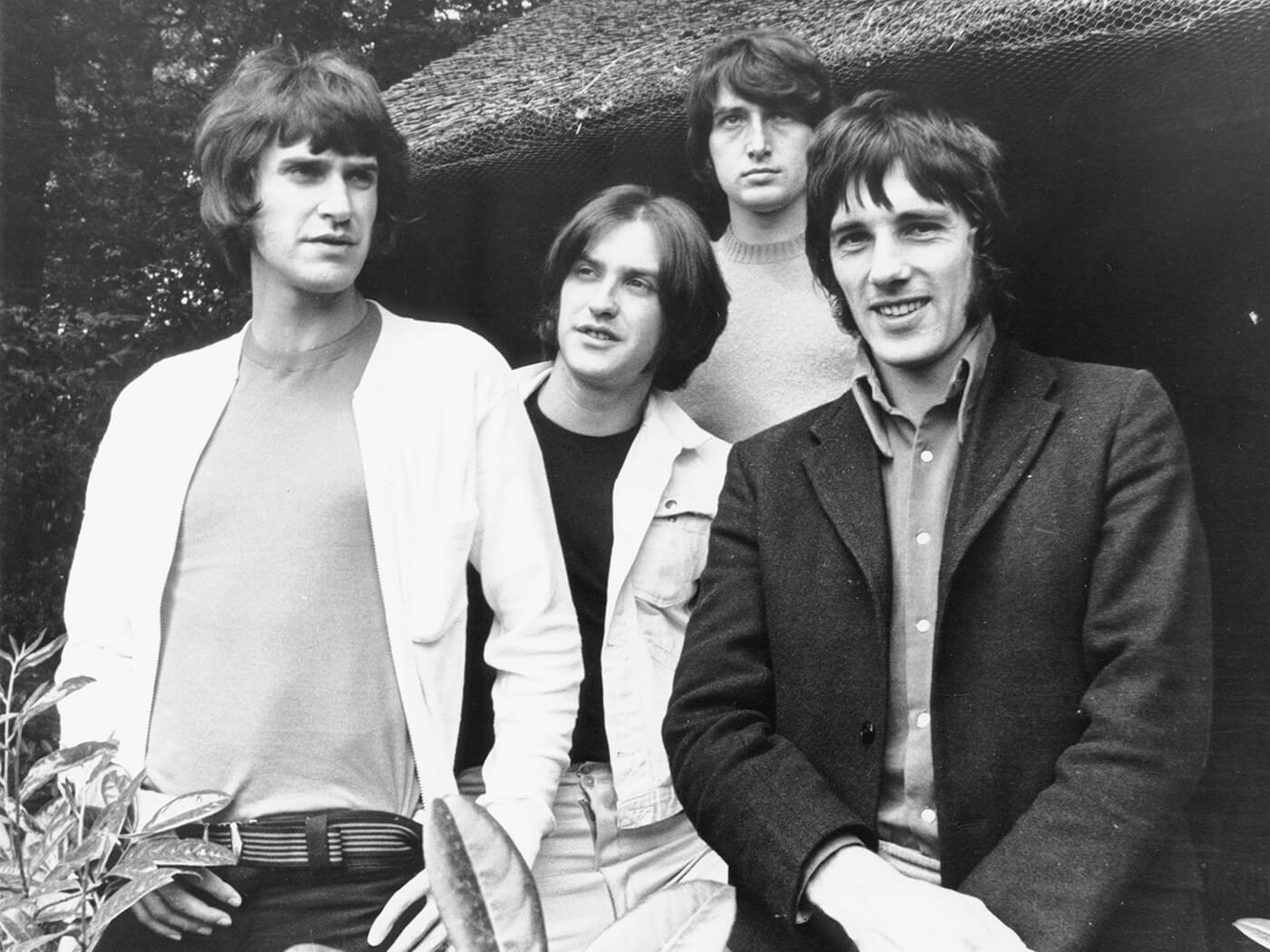

The Genius Of… The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society

The pioneers of the powerchord might have confounded listeners with 1968’s bucolic masterpiece, but Village Green…’s irreproachable songwriting and teeming guitar textures conjured a rose-tinted nostalgia like few others.

Image: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

“Oh, to be in England” romanticised 19th century poet Robert Browning in his idyllic poem Home Thoughts, From Abroad. Browning’s stirring image of an unspoilt pastoral haven was built on a particularly enduring idea throughout the 19th century. That being the appeal of leafy, quiet villages, awash with twittering birds and enveloped by rolling green fields. It’s an image that had an understandable resonance back in the soot-stained days of the industrial revolution. It was a notion sustained by the idea that the purity of this landscape was somehow in symbiosis with the soul. This imagined peacefulness reflected a simplicity of living that had been gradually eroded as the belching towers of progress re-shaped the country.

It was in similar pursuit of bucolic bliss, some 125 years on, which lay behind The Kinks’ decision to veer away from the exhilarating proto-metal and barbed character studies they had become famed for, and pen an LP that many would consider to be their magnum opus. Dominated by an acoustic-driven sound, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society was a conscious attempt by lead songwriter Ray Davies to not only rekindle and document the lost innocence of his suburban youth, but to flip the increasingly rebellious spirit of rock’n’roll on its head. While smart money might have been on the four-piece riff merchants following suit with many of their contemporaries, crank up their amplifiers and carve out a niche as heavyweight electric bluesmen for a new decade, The Kinks instead stood alone in proclaiming themselves the defenders of authentic – distinctly British – ideals. In the album’s opening manifesto, Davies spelled out their new contrarian calling. This was a band that was here to protect the ‘old ways’ from being abused.

The land of make-believe

The record’s concept originated with the song Village Green, first penned during sessions for the preceding album Something Else. Rolling through a shifting chord cycle in C minor, Davies poured out his desire to return to the whimsical lost paradise of his youth. “I miss the village green, and all the simple people.” Davies sang. The former deliverer of the lustful lyrics of You Really Got Me and other power-chord-based pile-drivers, was now facing psychological and physical exhaustion from the pressures of fame. Now he was walking that same path to an imagined paradise, previously trodden by many a long-dead poet.

Upon hearing the sentimental gem, Dave Davies understood precisely what his brother was getting at, in what was then conceived as the bedrock of a solo project; “At this time, we were very close, and our families were very close” Davies told Flood Magazine, “We used to see each other all the time, so I was privy to a lot of the stories and characters of that project. There were a lot of quirky things coming out of England in the 50s and 60s – these weird and wonderful English things that we thought were quite normal.”

Following numerous legal issues and an infamous four-year ban from touring America, it was eventually decided that Ray’s Village Green project would instead serve as The Kinks’ sixth studio album. With global ambitions now parked, the whole band, including bass player Pete Quaife and drummer Mick Avory, wallowed in Davies’ Arcadian vision. “I just immersed myself in being English and wrote about things that I cared about… I was writing old people’s songs for a world I thought was vanishing” Davies was quoted as saying in Ray Davies: A Complicated Life.

Sing Mr. Songbird

The main thrust of the album’s 15 tracks was provided by Ray’s acoustic Fender Malibu, a new-ish budget model introduced by the company in 1965, which found favour with Ray. He soon opted to use it as his primary songwriting instrument. It was notably heard previously on one of the band’s finest songs, the hazy Waterloo Sunset. Dave Davies opted to lay down some of the album’s assorted electric guitar licks using a combination of Ray’s ‘63 Sunburst Telecaster, his ‘59 Gibson Flying-V as well as a Bigsby-equipped Guild Starfire III. While amp specifics are sketchy, the notably lengthy sustain heard on the proto-goth Wicked Annabella definitely indicates the use of a solid-state amp, likely one of Fender’s first late-60s forays into transistor technology. Elsewhere, Dave’s trusty Vox AC30 was certainly used as a reliable workhorse as the four set to work at Pye Studios.

Though Ray’s acoustic chords formed the bedrock of the bulk of the songs, it was decided that the arrangements themselves could develop in numerous eclectic directions. Many of the styles explored would point the way to genres the band would further probe in ensuing years. The folky buoyancy of tracks such as Picture Book, Animal Farm and the summery title track were sequenced alongside the vaudevillian, piano and harmonium-led Sitting by the Riverside, the calypso-like Monica (complete with sun-kissed harmonic strokes), the ska-like slashes of All My Friends Were There and the twee psychedelia of the near Pink Floyd-ian Phenomenal Cat. Not to mention the aforementioned spookiness of Wicked Anabella and electric blues- heft of Big Sky’s supportive riff.

The record’s third track, the laddering Picture Book is one of the record’s songs which have now nestled into the public consciousness. Despite never being a single. Its popularity may be down to Green Day’s cheeky co-opting of its riff for their 2000 single Warning, and its use in 2004 on a Hewlett Packard advertisement. Nevertheless, it’s one of Village Green’s key pieces. Built around a four-note ascending riff across E, A, D and G (tripled by acoustic, electric and bass) Picture Book’s musical construction has the effect of tunnelling the listener further and further back through time, joining Ray in his deep dive into the well of nostalgia. The verse’s shimmering jangle was the result of an (unspecified) 12-string acoustic, played by Ray. In fact, it was the music-first construction of Picture Book’s arrangement which prompted its longing lyric “The whole magic of that track is that 12-string guitar and the snare drum with the snare off. It’s the way Phil Spector used to work – he had his sound and wrote songs to fit that sound.” he told Performing Songwriter.

Things as they used to be

Ray’s voluble acoustics sonically coalesce with the overriding theme of preservation and history, particularly on the record’s conceptual nucleus – Village Green. Its jovial arrangement also seems to conjure the spirit of an impish mediaeval balladeer.

But the album still found the space to allow Dave Davies the chance to show his teeth. We’re thinking of the frenzied break of Last of the Steam-Powered Trains wherein a relentless Davies gathers furious momentum and seizes the rhythm section in the gravitational pull of his overdriven hysteria. There’s also the hypnotic dissonance of the imposing riffs and tones deployed in the guitarist’s standout Wicked Anabella, complete with overdriven crunches and ghostly tremolo swoops. “This is rather a crazy track.” Dave was quoted as saying in the 33 1/3 take on the album, “I just wanted to get one to sound as horrible as it could. I wanted a rude sound – and I got it.”

These explosive moments aside, the immaculate arrangements of the (self-produced) record called for Dave to be generally much more considered in his approach. There’s high-octave punctuation applied to the sweet Animal Farm, a delicate guitar line which takes over Phenomenal Cat, and demands that it re-structures itself to mimic Waterloo Sunset’s sorrowful, descending note motif. There’s the unravelling arpeggios that spiral forth from the chorus of All My Friends Were There, and the elegant vocal melody-emphasising lick that tracks Do You Remember Walter?.

Village Green… finds both Davies brothers at their most creatively successful. Their musical synergy is mindful, mature and magnificent. Though it’s far from their most guitar-dominated album, it is the album that incorporates the guitar most gracefully. It’s used as a hook enhancing, emotion-wringing tonal carver, as well as a pained central spine, via Ray’s acoustic foundation.

Though its release, in November 1968, was initially met with confusion and rejection, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society weathered the storm. In retrospect, The Kinks’ sixth album was rightly hailed as one of the band’s most substantial and rewarding works. By taking that conscious step outside of contemporary thematic and musical trends, the album maintains a character all of its own. The astute arrangements – particularly in guitar terms – are largely responsible for painting that picture so vividly. Davies’ idealised village green has been discovered anew by the ears of successive generations. It’s perhaps an even more compelling vision now, as the romanticised picture of a perfect little England becomes an increasingly fading memory.

Infobox

The Kinks, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (Pye/Reprise, 1968)

Credits

- Ray Davies. – Songwriting, Vocals, Acoustic and Electric Guitar, Keys

- Dave Davies – Lead Guitar, Backing Vocals

- Pete Quaife – Bass

- Mick Avory – Drums

- Nicky Hopkins – Mellotron