Related Tags

Fuzz Was The Future: Satisfaction Guaranteed

In this final column in his mini-series on the birth of fuzz, JHS head honcho Josh Scott explains how a pedal that sold zero units in 1964 would change the course of music forever, with a little help from Keef.

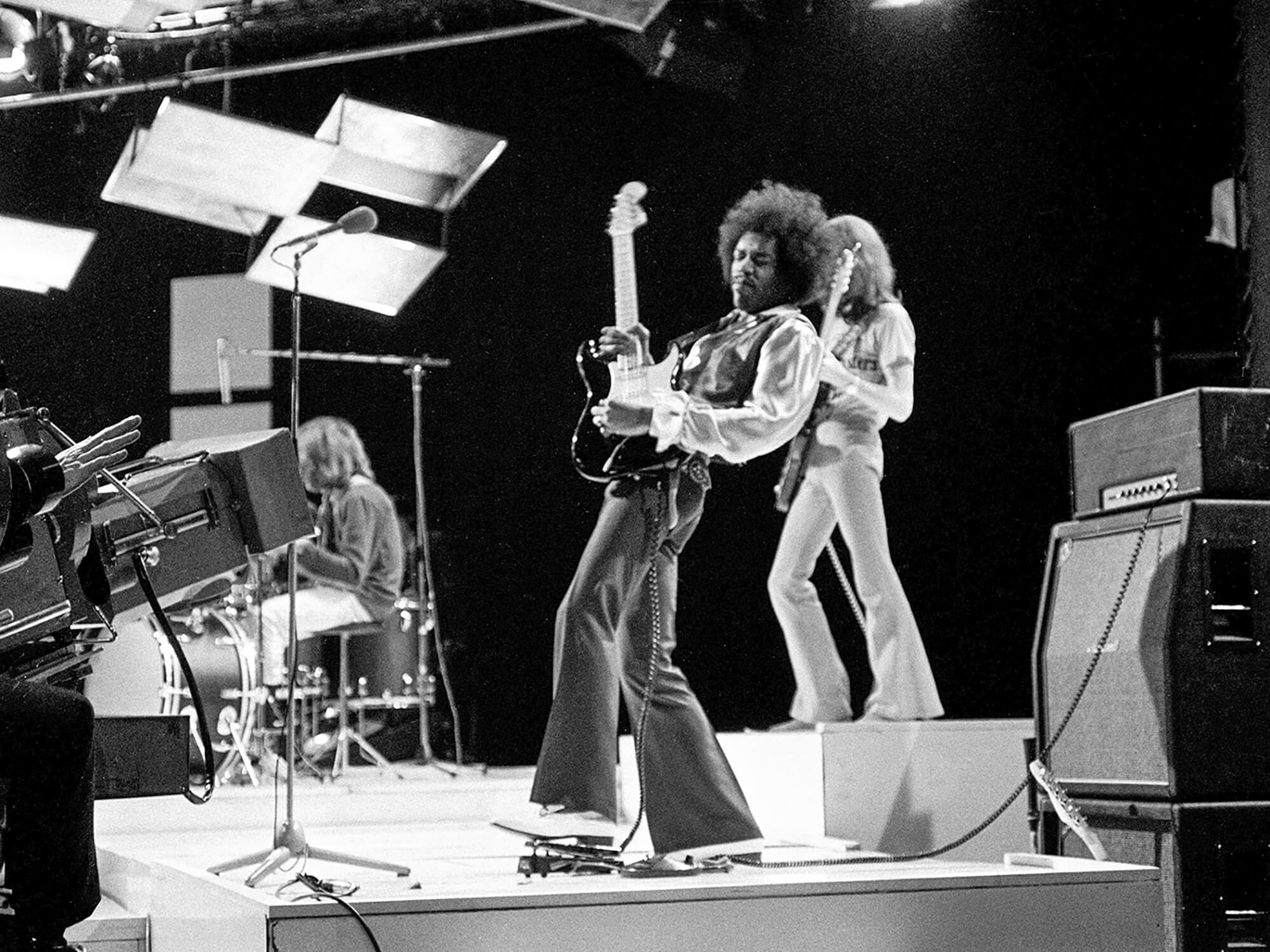

The Jimi Hendrix Experience on the BBC show Happening For Lulu, 1969. Image: Ian Dickson / Redferns / Getty Images

Well, folks, it’s been a trip. For the last four months we’ve charted the unlikely and remarkable birth of fuzz, from a one-chance-in-a-million studio accident to the creation of the first ever effects pedal: the Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-1. We’ve also covered how that particular box of wonder was marketed so terribly that it almost ended up as a footnote in the history of popular music. Almost. Not quite.

- READ MORE: Fuzz Was The Future: Now but not yet

So, how did fuzz end up becoming one of the defining sounds of rock ‘n’ roll, and how did the FZ-1 in particular overcome its disastrous product launch in 1962? The answer, as with so many things in life, is Keith Richards.

A new kind of sleepwalking

The Rolling Stones debuted as a band on 12 July 1962 at the Marquee Club in London. For those keeping track at home, yes, this was the same year that the Maestro Fuzz-Tone was released, but the Stones had slightly more success marketing their wares.

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had formed the band the year before, and by 1962 they were a rising force in the new sound of British rock. They released their first single, a cover of the Chuck Berry classic Come On, on 7 June 1963 and dropped their self-titled debut album on 16 April 1964.

Around this time, the Stones started gaining a reputation as (arguably) the first real “bad boy” musical group of that era, helped enormously by an article published in Melody Maker which asked readers, “Would you let your sister go with a Stone?” As their popularity grew, the Stones became regarded as the edgy, dangerous counterparts to the clean-cut and wholesome Beatles (despite the fact that the Fab Four were no angels). Think of it as a mid-century version of Blur vs. Oasis, but without Wonderwall.

In 1964, the Stones’ cover of Buddy Holly’s Not Fade Away peaked at No 3 in the UK and at No 48 in America, but they still hadn’t totally made it as a band. Not until 1965, that is.

Given that the Human Riff would later claim he once stayed awake for nine straight days, it may shock you to learn that Keith Richards was not the most consistent sleeper. In fact, he would regularly wake up in the middle of the night, inspired, so he got into the habit of leaving a hand-held Phillips tape recorder next to his bed to record these flashes of late-night genius. On the morning of 6 May 1965, Richards played the tape back as usual. He listened to a few minutes of himself noodling around on acoustic guitar, and then he heard it: a riff. The riff. A 10-note melody in the key of B that would catapult the Rolling Stones to number one on the charts in the UK and America; this was the golden ticket that every rock band dreams about. It was (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.

The remarkable thing is that Keith had zero memory of playing it the night before, and even in the recording he heard himself drop his guitar pick and begin snoring about two minutes after he laid down the riff. Feel free to bring that up next time your boss gets mad at you for wanting to nap in the middle of your shift; just tell them it’s your ‘creative space’.

But Keith knew a good idea when he heard it, so they wasted no time turning that riff into Satisfaction,” recording it four days later at Chess Studios in Chicago, and then at RCA, Hollywood, California on 12 May. Just one month after that bolt of midnight inspiration, Satisfaction was released as a single on 5 June 1965, and rocketed to the top of the charts. It knocked Sonny and Cher’s I Got You Babe off the top spot, and became the Stones’ fourth UK #1 and first US #1. It is ranked number 2 on both Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list, and has since been covered by everyone from Otis Redding and Devo to Britney Spears.

Happy accidents

Now, of course, it’s impossible to think of that iconic riff without the sizzling fuzz of Richards’ Maestro Fuzz-Tone, but here’s the kicker – the fuzz effect was never meant to be on the final track. Keith had used the FZ-1 as a placeholder for a horn section that he planned to re-record on the final track. Remember that demo record praising the FZ-1’s ability to mimic “booming brass and bell-clear horns”? Apparently that marketing line worked on Keith, at least.

(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction hit the record stores so soon after Richards had come up with the riff primarily because it wasn’t mean to be – the Stones’ manager had released the unfinished recording without the band’s permission. Keith didn’t realize it until he heard their song on the radio, and he was understandably horrified – what were people going to think? Bear in mind, people had only recently adjusted to racy hits like Bobby Darin’s Splish Splash and the Kingsmen’s Louie Louie. Were they ready for fuzz?

When Keith Richards plugged into the FZ-1 in 1965, it wasn’t just a step

in the evolution of rock, it was a step forward in sonic evolution

In a still-evolving world where the sound of broken, sputtering fuzz guitar wasn’t an ingredient for pop radio, this song could have totally tanked, which could have put an end to the Stones’ momentum before they even got started. But as any Rolling Stones fan knows, you can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you get what you need. Keith might never have got those horns as he imagined, but it turned out that Satisfaction – and by extension, the FZ-1 – was just what pop music needed.

The song would springboard the Stones from the fringes of the English rock scene to worldwide prominence and by extension, it propelled the sound of fuzz and the FOMO of young rebellious guitarists across the globe. From this moment, the FZ-1 flew off the shelves in high demand. Gibson went from selling zero FZ-1s in 1964, to selling over 3,000 in 1965 and a staggering 20,000 units in 1966. The tables had turned and “now but not yet” was officially over. It was just now.

The evolution of influence

So what does all this have to do with Marty Robbins and a sad country song? As Malcolm Gladwell would probably say, they were both tipping points for guitar. Don’t Worry created a circumstance that birthed an idea, and (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction finally delivered that idea to the world on a grand scale. A happy accident birthed the idea, and another accident gave guitarists and the music industry the push they needed to finally embrace a new form of distortion-driven rock.

As I’ve said before, sound is a technology, and technology isn’t just invented, it evolves. This is mirrored in the evolution of musical genres as well. West African antiphonies became American field hollers, and field hollers turned into folk music, which evolved into the Delta blues. The Delta blues adopted the guitar as its primary voice in the hands of players like Robert Johnson, Memphis Minnie and Muddy Waters, who in turn inspired guitarists like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Keith Richards. Even the Rolling Stones’ name comes from a Muddy Waters song. It’s all connected.

When Keith Richards plugged into that FZ-1 in 1965, this wasn’t just another step in the evolution of rock music, it was also a step forward in sonic evolution. Before him was Junior Barnard’s overdriven Fender Super amp on Bob Wills Boogie (1946), Willie Johnson’s piercing tube-saturated lead lines on How Many More Years (1951), Willie Kazart’s heavy rhythm sound from a broken speaker stuffed with paper on Rocket 88 (1951), Link Wray’s use of cranked amp distortion and tremolo on Rumble (1958) and of course Grady Martin’s busted mixer channel fuzz tone on Don’t Worry (1962).

Each of these songs had pushed the boundaries of acceptable guitar distortion a little further, and as a result these sonic pioneers were responsible for making that edgy and violent fuzz tone on Satisfaction a hit, each one slowly allowing more and more cultural permission for this new and radical sound of six strings to be fully distorted.

At first, players cranked their amps and tore their speakers, which gave an unassuming radio technician from Tennessee enough permission to put his broken sound into a simple stompbox that could sit at your feet. Each event gave the next a bit more freedom to explore. That said, it’s hard to fully understand the significance of these events in 2021. We so easily take for granted that Satisfaction was a smash hit in 1965, and we don’t realize the full impact that this song had. We see it decades later with Kurt Cobain stomping his Boss DS-1, creating a wall of sonic angst that literally broke the music industry and our perceptions of what popular music could do.

And if this is hard for us to understand in 2021, try to wrap your brain around how strange this was in 1965. Just a few years earlier the accordion was London’s most popular instrument. In the span of a decade, the electric guitar evolved from an instrument of clean and precise clarity to a weapon of massive, fuzzy destruction. One year after Satisfaction, Jimi Hendrix further evolved this sound with his release of Are You Experienced?, and by the end of the decade we had embraced the even more abusive guitar tones of Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath. If not for that accident in a Nashville recording studio in 1961, popular music would sound completely different. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the 1960s music and cultural revolution that we know would have never happened – at least not in the same way.

Marty Robbins’ 1961 recording session stands out like no other moment in music history, because it makes us ask, “What if it hadn’t happened?” Thankfully, the stars aligned, fate intervened, and some might even say that providence prevailed. Maybe we didn’t know it at the time, but fuzz was the future.

Join Josh for more effects adventures at thejhsshow.com.