Related Tags

Invention Has A Sound: The story of Mark Twain, a Martin acoustic and the world’s first guitar effect

JHS Pedals supremo Josh Scott continues his exploration of the evolution of guitar effects with the introduction of another icon of American history. Brace yourself, we’re going down river.

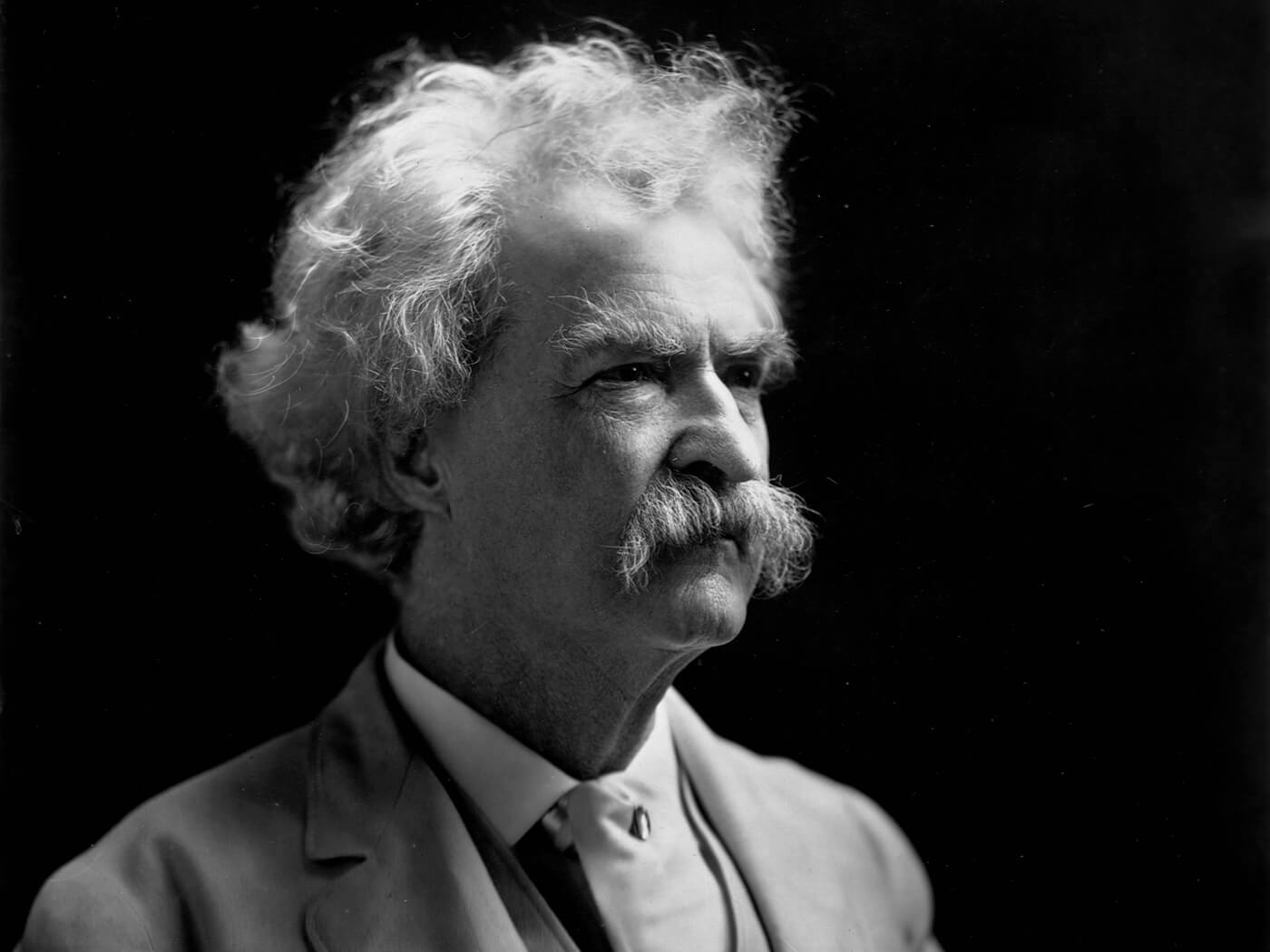

Mark Twain. Image: Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images

In our first dive into the long and fascinating relationship between electricity and the guitar, we caught up with Benjamin Franklin and explored the huge impact that George Beauchamp had on the history of our instrument. This time out I’d like to introduce you to another fellow whose name might not be instantly familiar to you – Samuel Clemens.

- READ MORE: Josh Scott explains why he made a musical about effects pedals… and why he’s just getting started

Clemens was a mid-19th century Missouri native who changed careers more often than Arnold Schwarzenegger (look, how many people can put Young Hercules and “Governor of California” on the same resume?). Clemens started as a Mississippi riverboat pilot, then served as a second lieutenant in a Confederate militia for two weeks before deserting to go west with his brother Orion.

In Virginia City, Nevada Clemens tried and failed to make it as a silver miner, and eventually went to work for a local newspaper called the Territorial Enterprise. This career, at long last, was the one that stuck, and Samuel ended up writing at least 17 books, some of which you’d probably heard of: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Prince and the Pauper, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Yup. Samuel Clemens became Mark Twain, the father of American literature. Now, I can hear you already: “But, Josh, this is Guitar Magazine, not Literary Review – why are you talking about Mark Twain?” Well, I’m bringing up Mr Twain because, believe it or not, he had something in common with us: he bought a guitar.

One day in 1861, as he made plans to avoid the Civil War and head out west with his brother, he purchased a used 1835 Martin Parlor acoustic for $10. He travelled the rest of his life with this guitar by his side; it was a constant companion

I’m not sure what first piqued Twain’s interest. Maybe he heard a particularly metal cover of Dixie or Hark! The Herald Angels Sing (two of the most popular songs in his day). Maybe he wanted to impress his girlfriend. Maybe he wanted something to help pass the time during his two-week wagon ride to California. Personally, I like to imagine that just like me, he heard a song, he connected with it and he wanted to make that kind of music himself.

Live alive

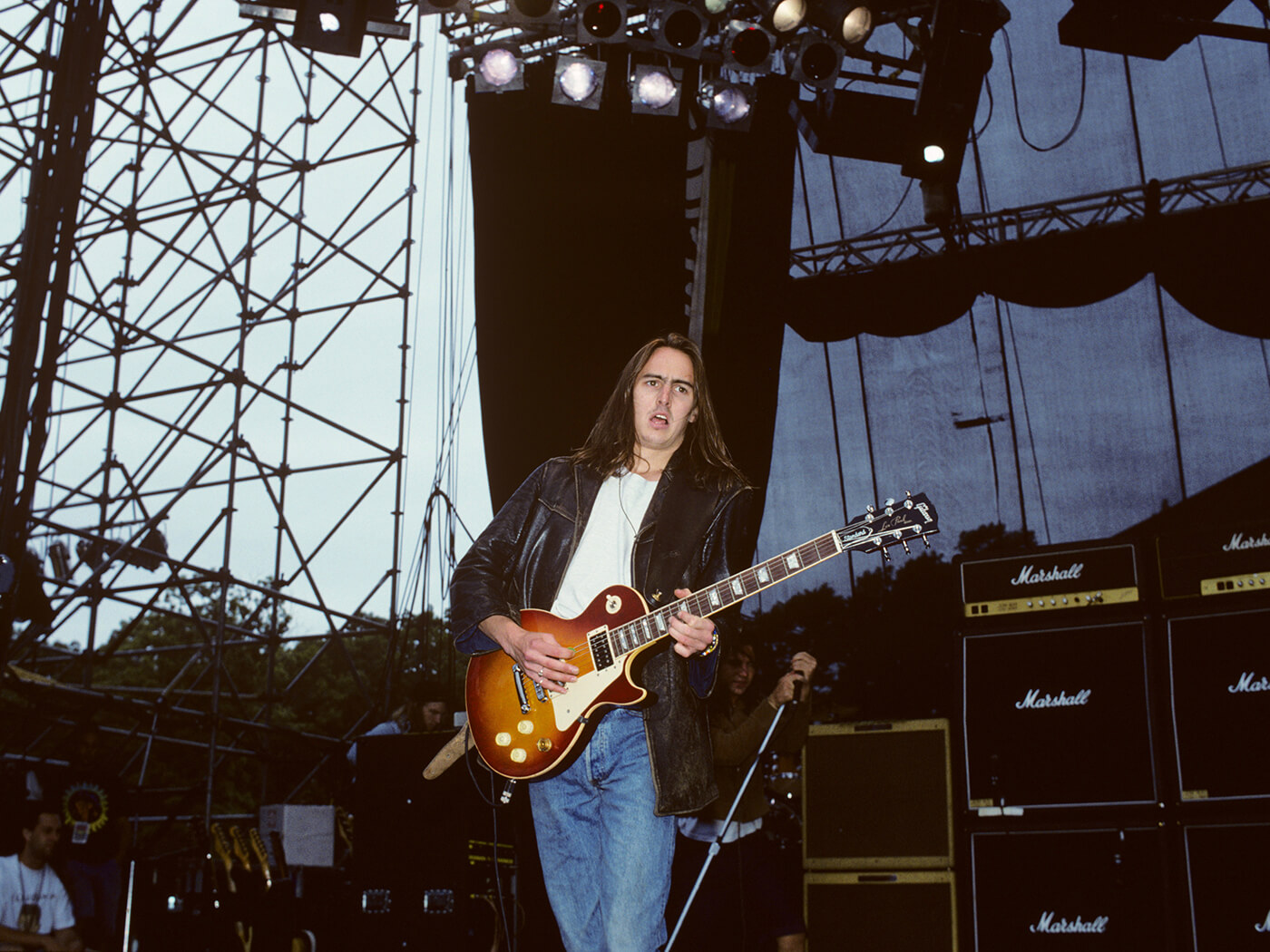

When I was 14 years old, I heard Pearl Jam’s Alive on my brother’s cassette player and realised that somehow, a guitarist in his late twenties had an open window into my ninth-grade soul. With the sound of that main riff and solo, Mike McCready might as well have been reaching out through the speakers and rewiring my brain. Until then, I had never been that interested in music, but this moment changed me. I had to have a guitar. I had to create the sounds that I heard in that song.

After pestering my mother about it for weeks, she finally brought home a beautiful Korean-made Synsonics Stratocaster copy, and suddenly I was part of a bigger story. I was Luke Skywalker, a young Jedi bursting with almost unlimited potential, part of an ancient and honourable order who held the world’s fate in their hands. And if that sounds dramatic, you obviously aren’t a real guitarist and I forgive you.

But unlike me, 26-year-old Mark Twain had never heard a single Pearl Jam song or experienced the perfection of Wonderwall, but the guitar still drew him in. The simple sound of his Martin acoustic guitar was enough – and this itself was part of a macroevolution dating back more than two thousand years, back to the day the first strings were attached to a piece of wood. The sounds that I heard coming from Mike McCready and Stone Gossard‘s guitars were a much further evolution of that same sound. And by the way, and if you’re interested in learning a little about inflation and celebrity culture, that $10 Martin of Twain’s was valued at $15 million in 2015. That’s enough to buy more than one million Synsonics Strat copies, and there’s no way my mom could have fit those in her station wagon.

Fantastic journey

So, how did we make the journey from Mark Twain’s acoustic guitar to Mike McCready’s Les Paul? It’s quite simple: 134 years of invention. Martin went on to create the dreadnought acoustic, Gibson made awe-inspiring archtop guitars, and as we learned last time, Rickenbacker merged the primitive guitar of the time with a new and exciting force called electricity. The electric guitar’s new voice demanded a new audience and set the guitar on its course for world domination.

Last month we spoke about the earliest experiments in electric guitar, but there are three more innovations in the world of pre-1960s electric guitar that are of pivotal importance to effects lovers. We’ll zoom in on the other two next time, but for today we’re going to explore the fascinating birth of everyone’s favourite shuddering, juddering textural wonder: tremolo.

Tremolo’s origins are equal parts clear and blurry. The term has different meanings depending on the context, but from a guitar player’s perspective, tremolo is volume modulation. In even simpler terms, it means that it is the sound of turning the volume on and off. It’s the same as taking the volume knob on your car stereo, playing a song, and turning it down, up, down, up.

A similar sound appears as early as the 1600s in classical music compositions. Later on, horn players began to cover the bell of their instruments to temporarily and rhythmically mute notes to create a rapid rise and fall in volume. In the 1930s, organs included a tremolo circuit inside their tube amplifiers that gave the organ a moving, fluttering tone. Even accordionists inspired tremolo guitar with the way they manipulated the accordion’s bellows to produce unique pulsating effects.

The right moves

Indeed, so popular was this effect that tremolo has the distinction of being the first-ever stand-alone guitar effect. Released in 1946 by the DeArmond Research company of Toledo, Ohio, it was called the Tremolo Control, model 601, and was designed by Harry DeArmond. Yup, the same Harry DeArmond who helped his brother John market the first-ever commercially available guitar pickup on the market, which they had created from parts found on a Model-T Ford.

About the same size as a shoebox, the Tremolo Control is perfectly simple, and rather familiar to modern guitarists: two control knobs called speed and increase, a handle, an input jack for your instrument, power cord and a pre-attached output cable that plugs into your amplifier.

Inside the enclosure it gets a bit more unconventional. The main thing is a canister that looks like a can of beans, which is full of liquid and also contains a little electrode. In use, a motor moves the can, which sloshes the liquid around, shorting out the signal whenever the fluid touches it, creating the tremolo effect. It might not pass modern health and safety standards, but it worked. Tremolo and guitar – friends forever.

The first known recording of a tremolo effect is a great deal more subtle however, listen carefully to Sugar Babe Blues by cigar-chomping blues singer Roosevelt Sykes in 1942 and you can just make it out in the background. By 1955 we were done with being subtle, and Bo Diddley put it front and centre of his smash-hit Bo Diddley. This track made tremolo famous, and started its journey to shape popular music with its swampy, mysterious tone. Without it, we wouldn’t have everything from Gimme Shelter by The Rolling Stones to Bones by Radiohead – it’s hard to imagine. For the first time, the guitar had artificial movement and a personality beyond its natural voice: it was the beginning of a new age of effected guitars.

Once I get my time machine up and running – which should be any day now – I’m going to visit our old friend Mark Twain at some roadside saloon, and we’ll start a Western Americana Grunge band. In the meantime, I’m confident that he’d be proud to know that he played a part not only in the renaissance of American literature, but in a story that connects millions of people from all across the world: the tale of the ever-evolving guitar.

For more from Josh Scott check out thejhsshow.com.