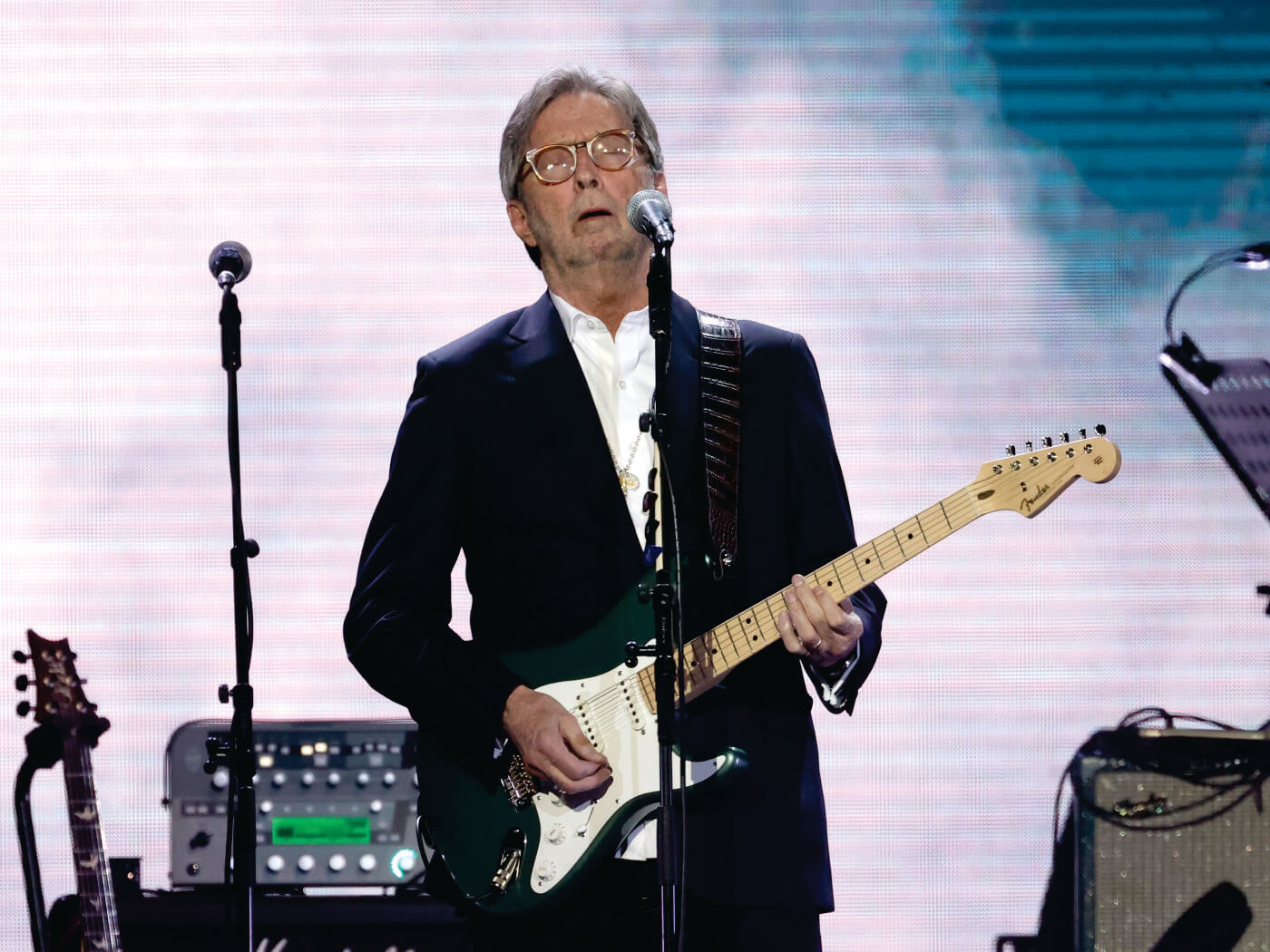

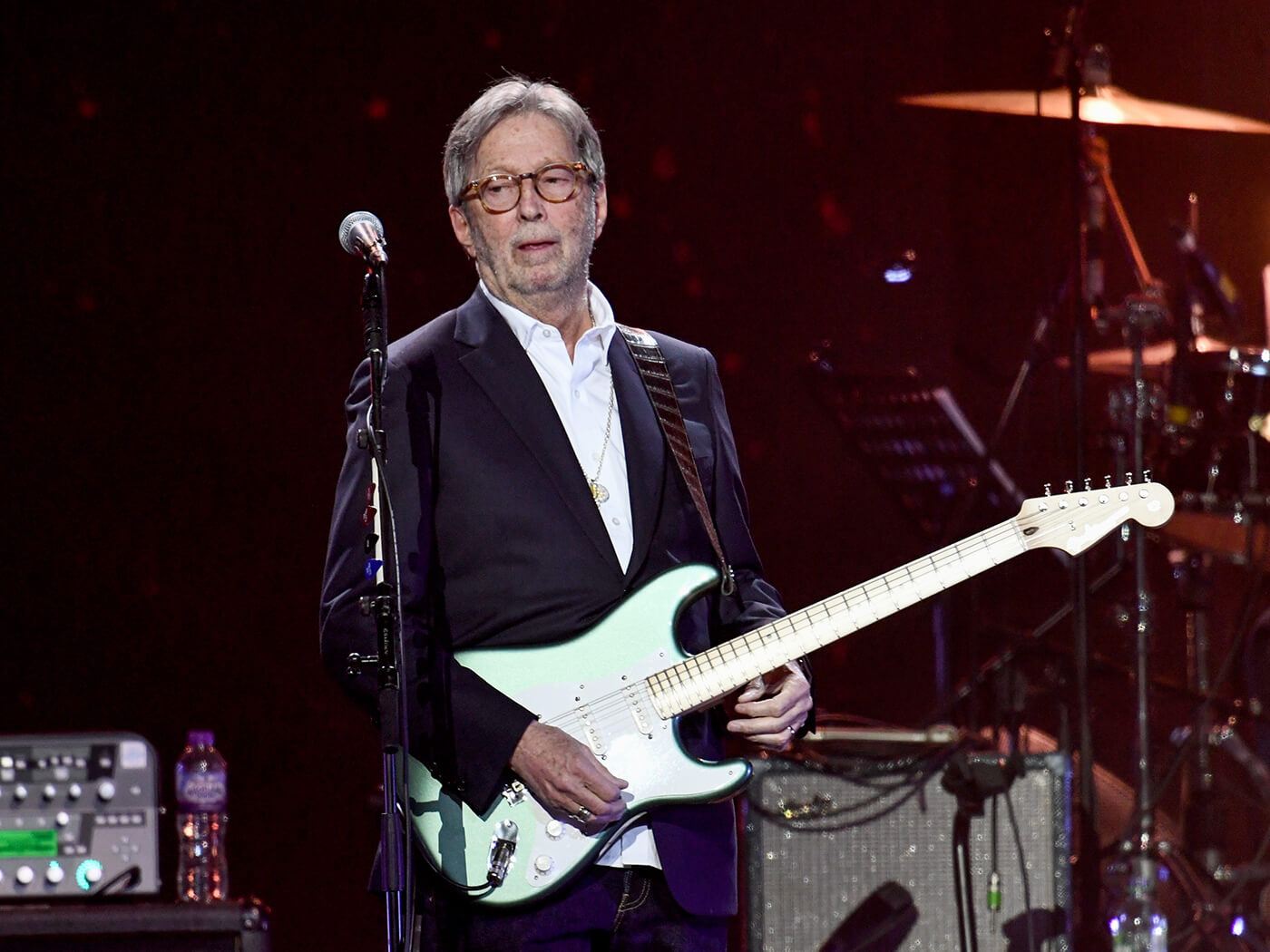

Guitar Legends: Eric Clapton – the birth of a legend

From upstart beginnings in the early 60s, Eric Clapton soon established himself as one of the decades’ most lauded players. Here’s a Part 1 guide to the man jokingly dubbed Slowhand.

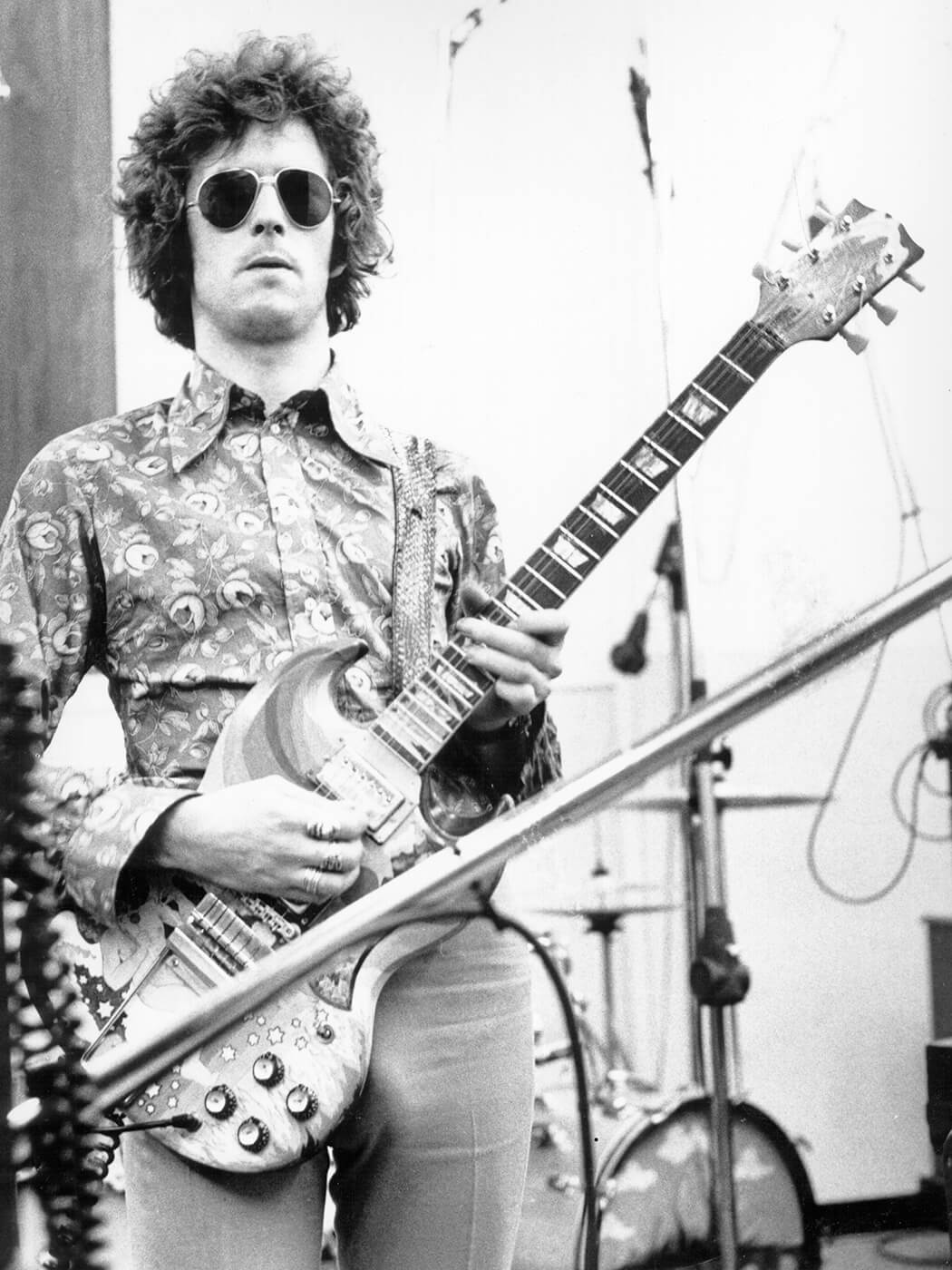

Eric Clapton. Image: Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images

When it comes to breadth of influence in the world of electric guitar, there are few more powerful than Eric Clapton. Over a recording career which has spanned 56 years (he’s now 75 years old), Clapton has pioneered new guitar/amp combinations, named a specific tone, has his surname as descriptor for playing vibrato a certain way, set world records when selling his own guitars, set a record for Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame awards, equalled Grammy-winning hauls and more.

All that kerfuffle about the ‘Clapton is God’ graffiti in the 60s? Well, if a God is indeed omnipotent and influences the behaviour of all of us (guitarists), then maybe it’s not so ridiculous? If obviously very flattering.

Conveniently for this two-part overview, of EC’s sounds and style, Clapton’s mammoth career has unfolded in quite definable stages… as has his style and gear. From his first taste of a £2 Hoyer guitar and fandom of Bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, Clapton has immersed himself in his craft.

He once said he loved the blues as it mirrored his own feelings about his troubled youth. “It was always one man with his guitar versus the world. He had no option but to sing and play and ease his pain.”

Here’s to a lifetime of hurtin’, decades of playin’, and some Godlike gear.

In his own words

“Early in my childhood, when I was about six or seven, I began to get the feeling that there was something different about me.”

“I sought my father in the world of the Black musician, because it contained wisdom, experience, sadness and loneliness. I was not ever interested in the music of boys. From my youngest years, I was interested in the music of men.”

“When all the original blues guys are gone, you start to realise that someone has to tend to the tradition. I recognise that I have some responsibility to keep the music alive… and it’s a pretty honourable position to be in.”

Early beginnings…

Of when he got given that first Hoyer aged 13, Clapton’s since admitted he initially “got nowhere” on the guitar, saying, “I started when I was 13… and gave up when I was 13 and a half.” For a while, he became obsessed with cycling instead.

But Clapton cannily managed to sell the Hoyer two years later (for a fiver!) and replaced it a George Washburn Spanish acoustic and suddenly made progress. Coupled with hearing Robert Johnson’s King Of The Delta Blues Singers LP plus Muddy Waters, Sonny Terry/Brownie McGhee and Big Bill Broonzy, at around the same age, Clapton was up and running. By early 1963, he’d fallen into an apprenticeship in local R&B band The Roosters, playing a 1960s double-cut Kay Jazz II his grandmother (‘mother’) Pat helped buy on hire purchase.

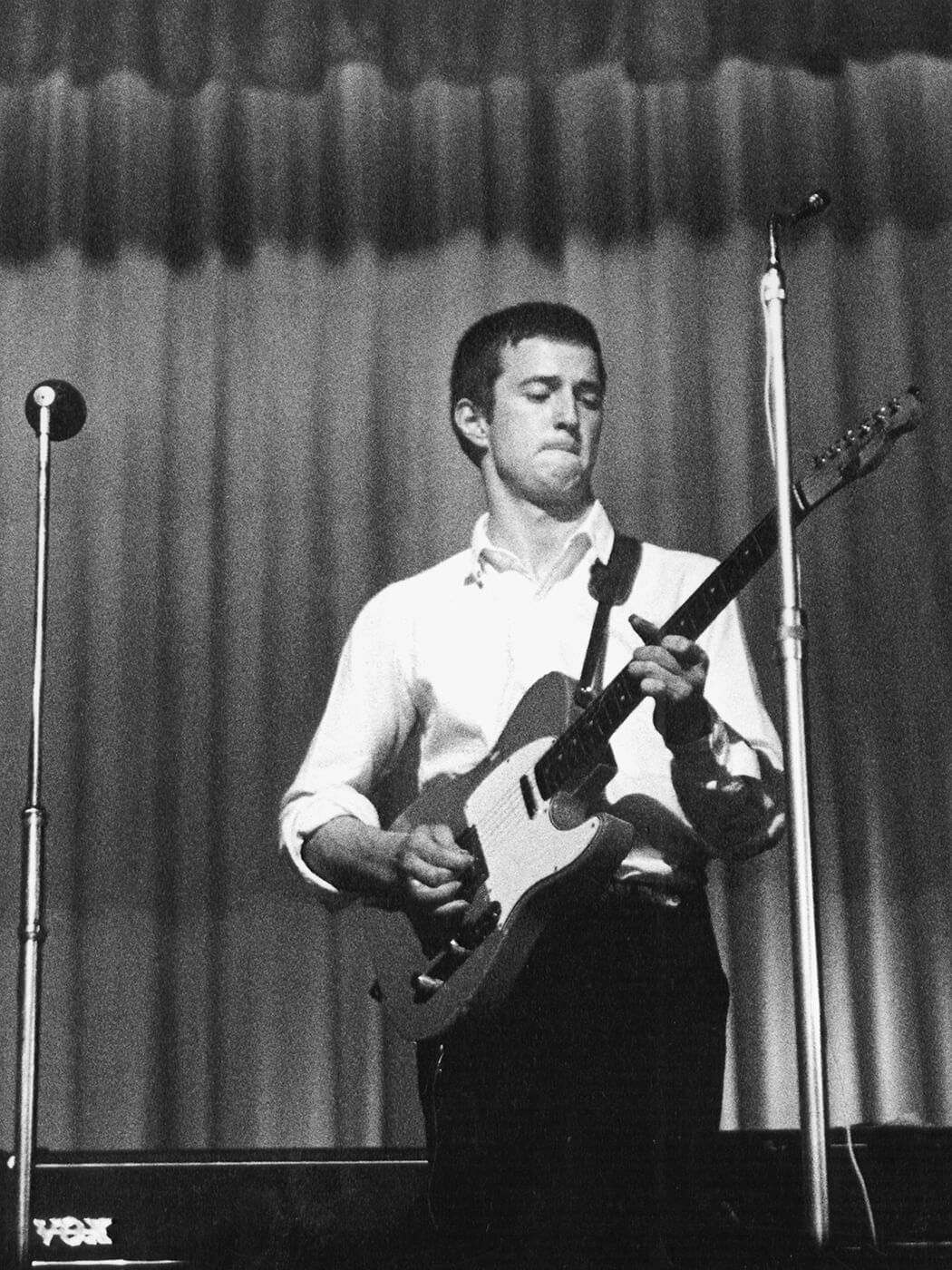

The Yardbirds and the red Tele

Soon he was asked to join The Yardbirds, where he started to really make his name. “There was only a handful of bands, and anyone that could play Sam & Dave, Stax and Motown was a master,” Clapton wrote in his autobiography.

He was then playing a red 1963 Fender Telecaster, with plenty of pickup power. But that guitar wasn’t even Eric’s – it belonged to the Yardbirds’ management, and after Eric had left the band, his replacement Jeff Beck played it prior to acquiring his fabled Fender Esquire.

Five Live Yardbirds is a crucial document of Brit R&B: it’s possibly viewed through rose-tinted glasses due to Clapton’s later stardom as it’s rough, raw and shoddy in places, and don’t expect perfectly-phrased soloing from ‘God’ at this point. But Clapton clearly had fire… even when playing in the wrong key. He became famous in his own right. As Yardbirds drummer Jim McCarty, noted, “Normally, everyone would go for the lead singer. It was different in our band.”

Clapton played a Gretsch Chet Atkins Model 6120 on Ready Steady Go! with The Yardbirds, but that wasn’t his either, nor in likelihood the Fender Jazzmaster he occasionally toted. Even back then, there were big flashy ‘video guitars’ that simply looked ‘better’ for the cameras.

There was one iconic guitar he did buy back then, though, even if it was more often seen in the hands of bandmate Chris Dreja: a cherry red 1964 Gibson ES-335. It was essentially the ‘genuine’ version of his early Kay II, and would rise to the top later…

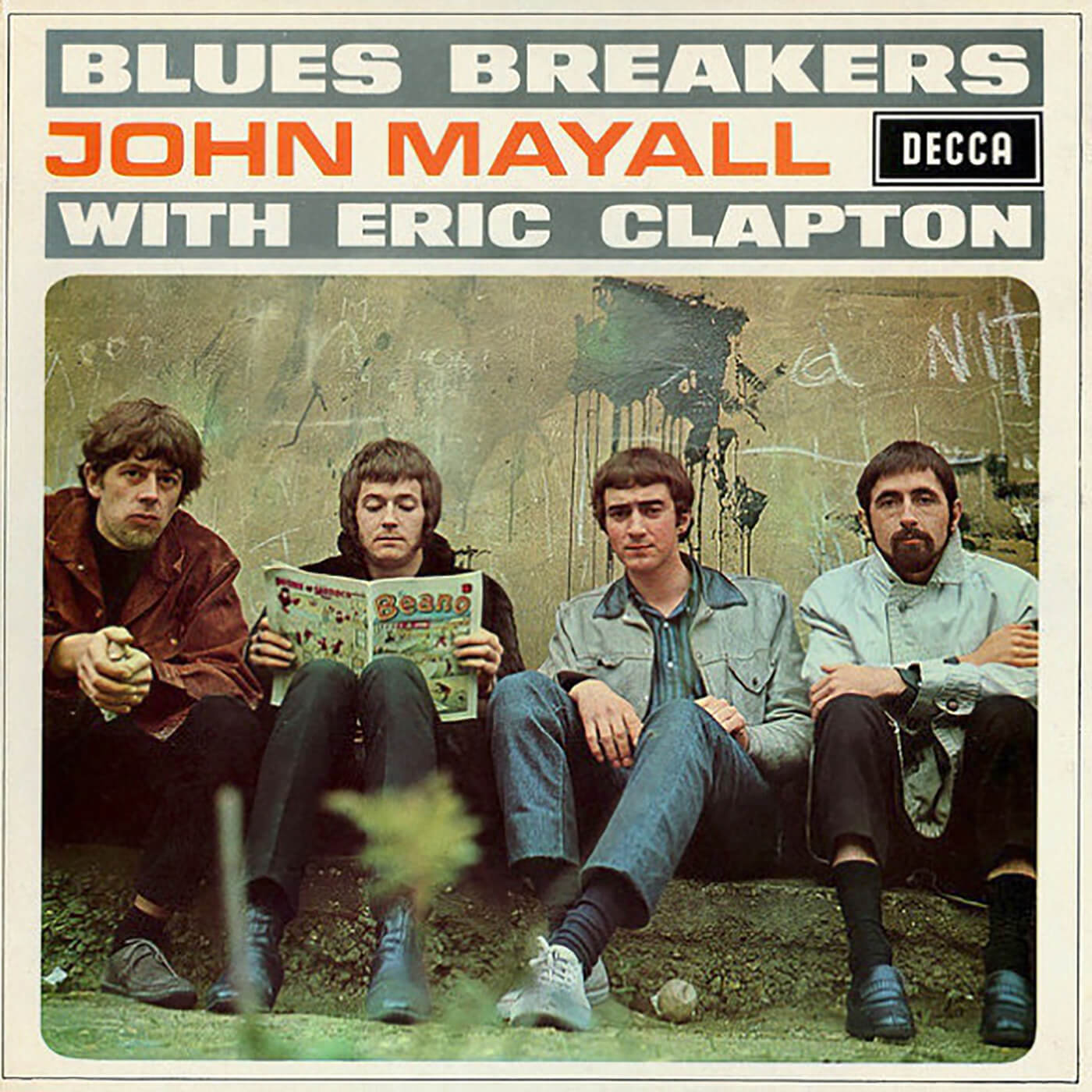

British blues and the Beano burst

Clapton didn’t hang around long in The Yardbirds, famously turning his nose up at the ‘commercial’ direction of the psych-pop banger For Your Love. Ahh, the unwavering principles of youth. No matter, as it was best for both parties.

With incomers Jeff Beck (then Jimmy Page), The Yardbirds would blossom into a great hard psych-rock band: Clapton sought solace and purist knowledge with Brit blues elder John Mayall. “John Mayall wanted me to play in the clubs, in his blues band, with no mention of any TV or records or none of that,” Clapton remembered approvingly.

But Eric was already well-known enough to get named billing on the LP sleeve and Blues Breakers Featuring Eric Clapton quickly became known as ‘The Beano Album’, due to the comic book Eric was holding on the cover photo.

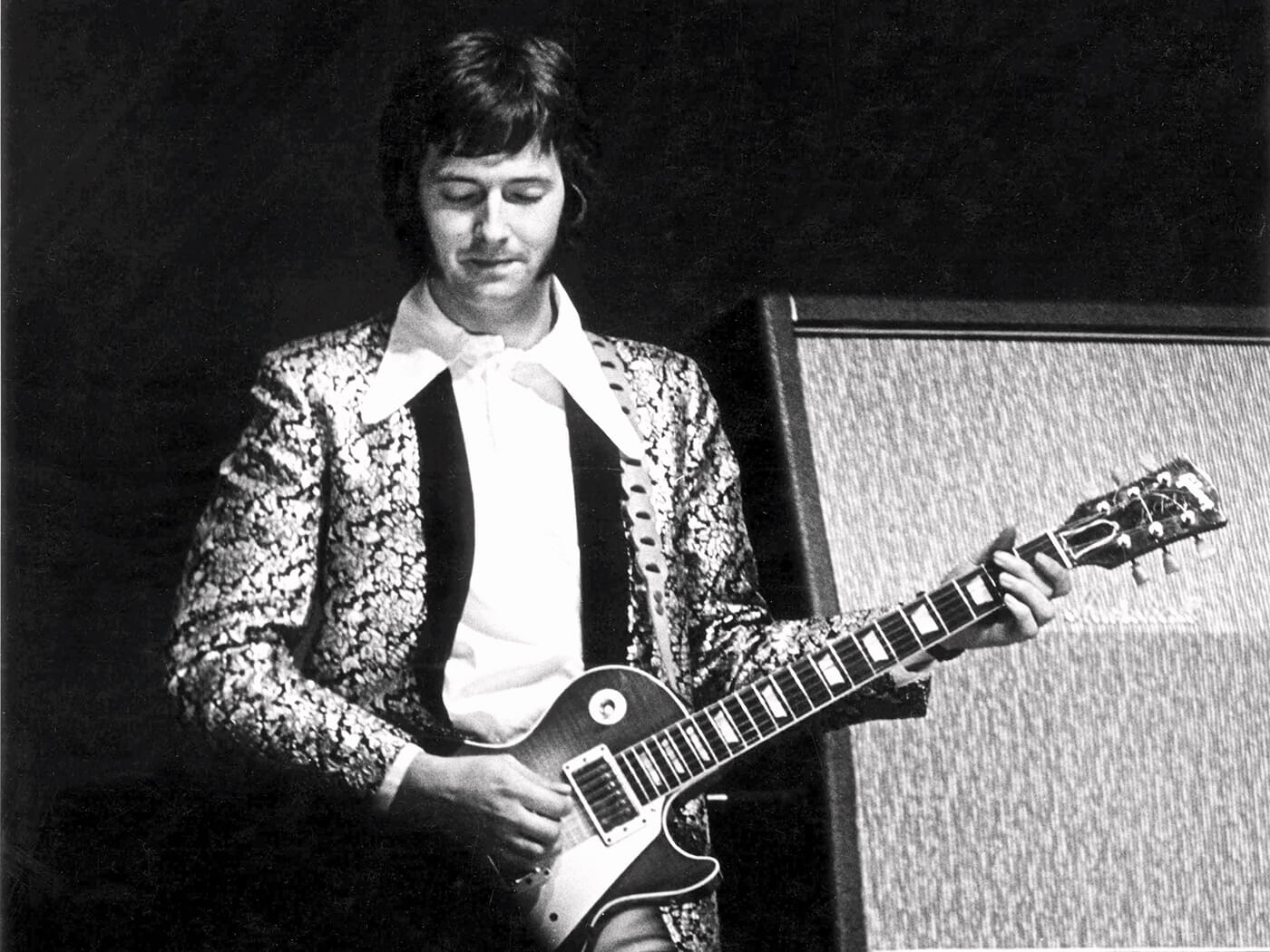

It was The Bluesbreakers that Clapton delivered his first major contribution to modern guitar 101: plugging a Gibson Les Paul Standard into a Marshall combo. The ‘Beano’ LP was Clapton’s first fully realised album as a blues player and also a seminal blues album of the 1960s. This is the real beginning of the Clapton legend. EC’s Les Paul itself was later stolen but from Clapton’s memories of it’s “very slim” neck it’s assumed it was a 1960 burst, and the impact of the album itself has added much to the folklore of ’58-’60 bursts.

Clapton’s tone on the album remains a benchmark in electric guitar over half a century on, and all blues rockers in its wake – from Peter Green to Joe Perry to Gary Moore to Joe Bonamassa – would be bowled over. Fledgling producer Jimmy Page worked on some Bluesbreakers B-sides, remembering, “When Eric was with the Bluesbreakers, it was just a magic combination. He got one of the Marshall amps, and away he went. I thought he played brilliantly then, really brilliantly.”

Clapton’s influence persuaded Gibson to reintroduce the singlecut LP from 1968 (from 61 to 68, they were only making SG ‘Les Pauls’ – a guitar Les Paul himself wasn’t particularly fond of, and from which he had his eventually name removed).

The big win was the t-o-n-e. Les Paul humbuckers were high output in comparison to the competition, and the Marshall itself was a 45-watt 1962 model 2×12 (JTM 45). It had UK-made KT66s output valves, which have a more refined mid-range and clearer top end than more regular EL34s or 6L6s: the modification was first made by Marshall to reduce costs. Learn some more about valves here and here.

Eric mostly recorded at full stage volume, even in the studio. When engineer Gus Dudgeon complained everything was simply too loud on the ‘Beano’ sessions, Eric simply replied: “That’s the way I play.” Clapton eventually had to be baffled into his own booth, with blankets, pillows and a grand piano cover as insulation. According to Mayall, “Even then, his playing made everything in the studio rattle.”

A fool and a firebird – Cream rises to the top

Despite Mayall providing Clapton with fame, encouragement and access to his own extensive blues record collection, the then 21-year-old guitarist remained restless. As with the Yardbirds, he again left after just one album. He now wanted to reach new musical lands, but his next outfit Cream was always going to be a difficult vehicle to travel in. The trio loved jamming together, but were they a ‘real’ band?

Things didn’t look promising when they couldn’t even decide who should sing – not because they were fighting for the spotlight, but because none of them wanted to! It didn’t help that there was open hostility between Bruce and Baker.

Named as they were “the cream” of mid-60s London’s musos, a “sensational groups’ group” according to Melody Maker, the alliance of Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker soured after 30 months, in what Eric later called a “shambling circus of diverse personalities”. They all knew it from the get-go. Baker later noted: “There were problems very early on. The only thing that held the band together was its success.” But when Cream did successfully gel, they were immense.

Eric’s Bluesbreakers Les Paul was stolen from an early Cream rehearsal, never to be seen again (not for definite, anyway) but Andy Summers – then of Zoot Money’s band – sold him a replacement.

Clapton also had what’s known as the Bigsby ‘Burst, another Les Paul, but this guitar seems to have been borrowed albeit on a long loan. The Fresh Cream� debut album was likely recorded on a mix of a borrowed Les Paul and the Bigsby Burst. Note that the Summers Burst, one of three LPs he had access to around this point, sporadically had its pickguard removed: that’s one way of recognising it in photos.

From Disraeli Gears he also had a black 50s Les Paul Custom that once belonged to Paul Kossoff, but he was still looking for something else.

And so it was that Clapton’s ‘Fool SG’ became one of the most famous guitars of the late 60s. In his 2007 autobiography, Clapton wrote, “The Fool were two Dutch artists, Simon and Marjike, who had come over to London from Amsterdam in 1966, and set up a studio designing clothes, posters, and album covers. They painted mystical themes in fantastic vibrant colours and had been taken up by The Beatles, for whom they had created a vast three-storey mural on the wall of their Apple Boutique on Baker Street, London.

“I asked them to decorate one of my guitars, a Gibson Les Paul [early SGs were called SG Les Pauls until the jazz legend objected], which they turned into a psychedelic fantasy, painting not just the front and back of the body, but the neck and fretboard too.”

Marijuana Koger described the overall theme of the design as “good versus evil, heaven versus hell, and the power of music in the universe to rise above it all as a force of good.” Far out. The artist pair were actually collectively known as The Fool from later, from when they worked on the Apple building, but ‘the Fool SG’ name has stuck in retrospect.

It all seemed strange, though. Less than three years previously, Clapton was a diehard blues purist: now, he was fully embracing psychedelia. Hanging out with Jimi Hendrix had a much deeper effect on Clapton than just him teasing his hair into a white boy ’fro.

Armed with The Fool SG, Eric Clapton refined what’s become known, in a term rather reflective of the attitudes of the time, as the ‘woman tone’. In 1967, Clapton told Beat Instrumental, “I am playing more smoothly now. I’m developing what I call my ‘woman tone.’ It’s a sweet sound, something like the solo on I Feel Free. It is more like the human voice than the guitar. You wouldn’t think it was a guitar for the first few passages. It calls for the correct use of distortion.”

Essentially, it was originally the sound of a Les Paul, or more often his Gibson SG, plugged into a Marshall amplifier – by now 100-watt stacks – with the tone setting(s) on the guitar turned almost all the way down and the volume full up. Cream’s Sunshine Of Your Love, Tales of Brave Ulysses, and Strange Brew are also classic ‘woman tone’ tracks, and listen to Cream’s Disraeli Gears for maximum Fool SG action.

That second album was so-named because Clapton had been talking about cycling again, and Cream roadie Mick Turner – attempting to sound knowledgeable about dérailleur gears – said “Oh yeah, Disraeli Gears” instead. Britain’s 19th-century Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was sadly far too dead by then to offer comment.

Clapton also played the Fool SG as his main live guitar, debuting it in public at Cream’s first US show in March 1967 at the RKO Theater in Manhattan, and stuck with it until late spring the following year. Hear it on the lauded March 1968 Winterland recordings, including Crossroads and Spoonful on Live Cream I & II.

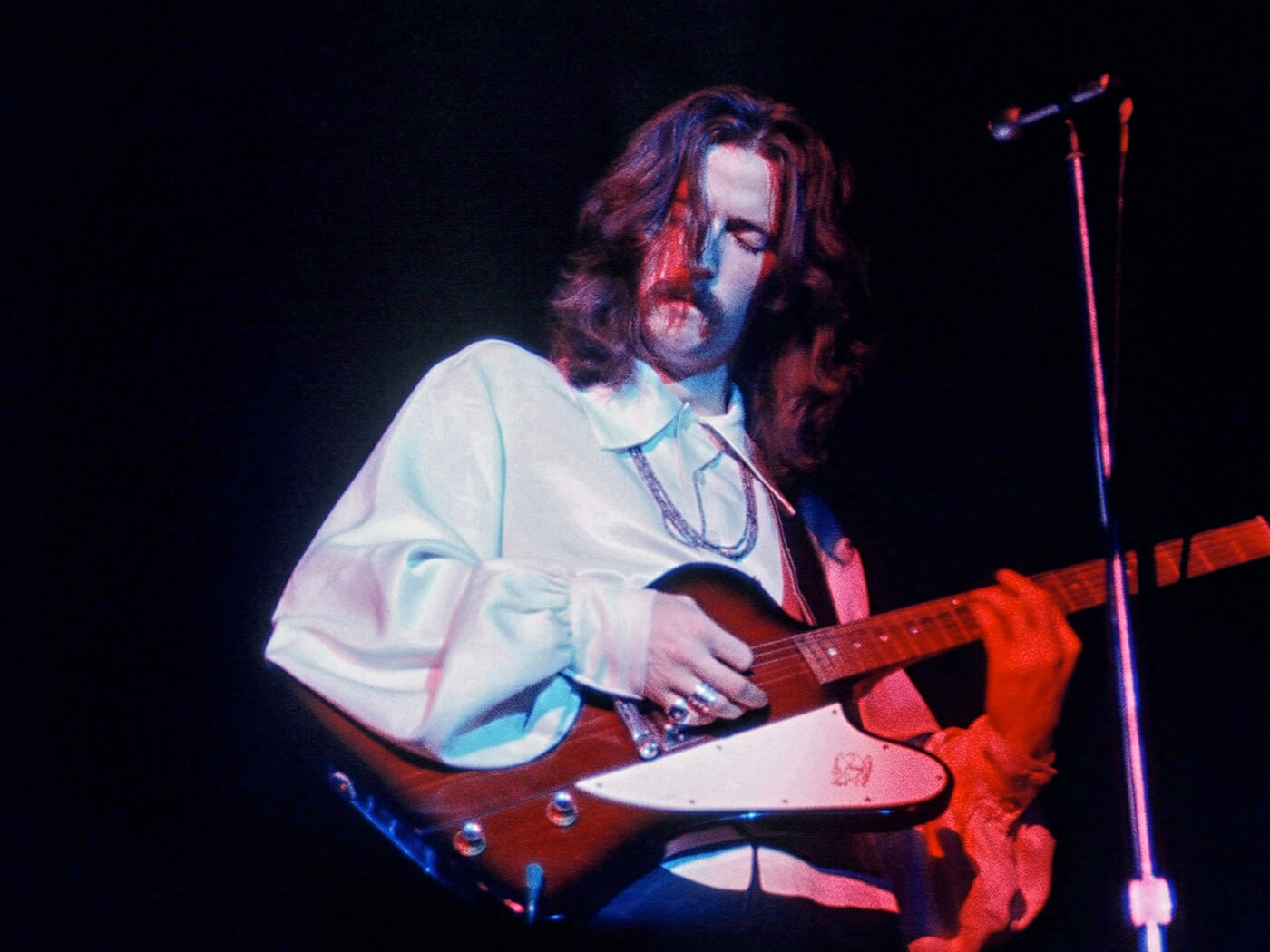

Clapton had two other main guitars in later Cream… and neither was a single-cut Les Paul. He started to play the cherry red Gibson ES-335 he’d bought while in The Yardbirds, but rarely then played. One assumes Clapton’s love of Freddie King was the inspiration for getting his ES-335 (King was the reason he first wanted a Les Paul, too, inspired by the cover of FK’s Let’s Hide Away And Dance Away of 1961) and it was famously used during Cream’s farewell tour in the autumn of 1968.

The tour culminated in two concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in November 1968, and in the second concert of the day, Clapton played this ES-335 whilst he used a Gibson Firebird I in the first concert. In December 1968, Clapton went on to cut Cream’s Badge and other tracks with this 335, released later on Cream’s Goodbye album (released 1969).

The Gibson Firebird I also dated from 1964, but was likely bought mid-US tour in 1968. On the second day of a three-day residency at the Philadelphia’s Electric Factory, Cream’s tour expense ledger for April 13 reads: “Musical equipment – $905.50” That’s $6,800 in 2020 money. If that outlay didn’t include the Firebird, that’s an awful lot of straps and picks.

The Gibson Firebird I is an incredibly simple guitar: mahogany ‘wings’, a nine-ply mahogany/walnut thru-body, just one bespoke-design pickup, a combination stud bridge/tailpiece, nickel hardware, dot inlays, and no neck binding. Aesthetically, they were the very opposite of luxuriantly-flamed bursts. Firebirds sounded smokin’ hot though. Clapton later recalled: “I remember one night in particular with the Firebird. It was a Cream show in Philadelphia and it was one of the greatest gigs I ever played.” New guitar, of course!

Cream only managed four quick-fire albums in just over two years, with the final two – Wheels Of Fire and the posthumous Goodbye – both being half studio/half concert recordings. In broad terms, Wheels… is with The Fool, Goodbye with the ES-335 and Firebird. Cream’s most famous valedictory track, Badge was recorded on the ES-335.

The cherry 335 was also played by Clapton in his appearance in The Rolling Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus movie of December 1968, as part of impromptu ‘supergroup’ The Dirty Mac (primarily EC, Keith Moon on drums, Keith Richards on bass and John Lennon on guitar/vox).

Blind Faith in the future

Perhaps surprisingly, the dismal dysfunction of Cream didn’t put Clapton off playing again with big stars. By early 1969, he was jamming once more with Ginger Baker alongside Steve Winwood, whose own Traffic had temporarily split. Ric Grech (bass) soon joined from the band Family.

Blind Faith were even more short-lived than Cream, managing just one album and tour. Winwood later rued how the members’ various managers could only see the upside of such an alliance: “They wanted a supergroup… and we didn’t.” Indeed, the initial official line was that Clapton was making a solo album just with some famous help.

Blind Faith’s music was wholly different to Cream. Steve Winwood’s ‘white soul’ voice and Hammond organ brought much more of an R&B tinge to the music, and the songs’ tighter arrangements were in stark contrast to Cream’s frenetic psychedelic blues improv. Standout track Can’t Find My Way Home (written by Winwood) is hymnal compared to much of Clapton’s brutal mid-60s power playing, and EC’s own In The Presence Of The Lord hinted at some higher power he was trying to reach. It also sounded very much like what we’d later hear on his solo albums.

Clapton had duly changed gear again – now often playing a Telecaster with Strat neck (see BF’s introductory Hyde Park show), more of which later. The album also included Clapton’s first significant forays into acoustic recording, playing a custom 12-string built for him in 1969 by Tony Zemaitis which EC nicknamed ‘Ivan The Terrible’, for some reason. Jimi Hendrix had a Zemaitis 12-string from 1967. Alas, Blind Faith crumbled as quickly as they’d formed. A lack of material beyond their debut album meant they reverted to playing Cream songs live as padding… the very same songs Clapton was trying to escape.

Post Blind Faith’s split, Eric sought solace in backing his friends Delaney & Bonnie, who he’d recruited as Blind Faith support in the US. The master was helping out his apprentices. So it was that Eric Clapton saw out the decade with a rootsy US duo, D&B’s Live With Eric Clapton album being recorded in December 1969 at Croydon’s Fairfield Halls. It was time for rethink.

Clapton’s amps and effects in the 60s

Clapton’s backline and effects were pretty standard in the 60s.

In The Yardbirds, he plugged the Tele into a Vox AC-30. With Mayall, it was a 45-watt model Marshall 1962 2×12 combo (JTM 45) before he cranked up in Cream with 100-watt Marshall heads and 4×12 cabinets, using two full stacks. Cream were famously loud. In Cream he also made use of a Vox wah pedal, a brand he stuck with for decades. There’s some speculation that he also used a Dallas Rangemaster Treble Booster pedal with Mayall and Cream, but ‘Beano’ producer Mike Vernon insists EC didn’t use pedals. Still, there’s nothing like a bit of mythology to inflate vintage prices and demand for reissues.

Up to 1967-ish, Clapton used very light strings, favouring .08s for the E and B strings, and a Fender Rock ‘N’ Roll E string for his third G string… hence the original “Slowhand” joke for his constant string breaking. No wonder he needed maximum tone from his guitars and amps. (As usual, links are mostly to modern equivalents of Clapton’s gear with genuine vintage pieces often prohibitively expensive.) By the time of Blind Faith, Clapton had added Fender Dual Showmans to his backline.

Essential listening

The Blues Breakers’ ‘Beano’ album is standard issue for anyone wishing to understand the roots of blues-rock wailing, but Clapton actually cut a broad range of styles throughout the 60s. Cream’s records remain remarkable. Here’s a playlist showing how his playing developed throughout the 1960s:

Playing style

Make sure you study How To Play The Blues Like Eric Clapton, and all of the blues primers in Guitar.com’s lessons.