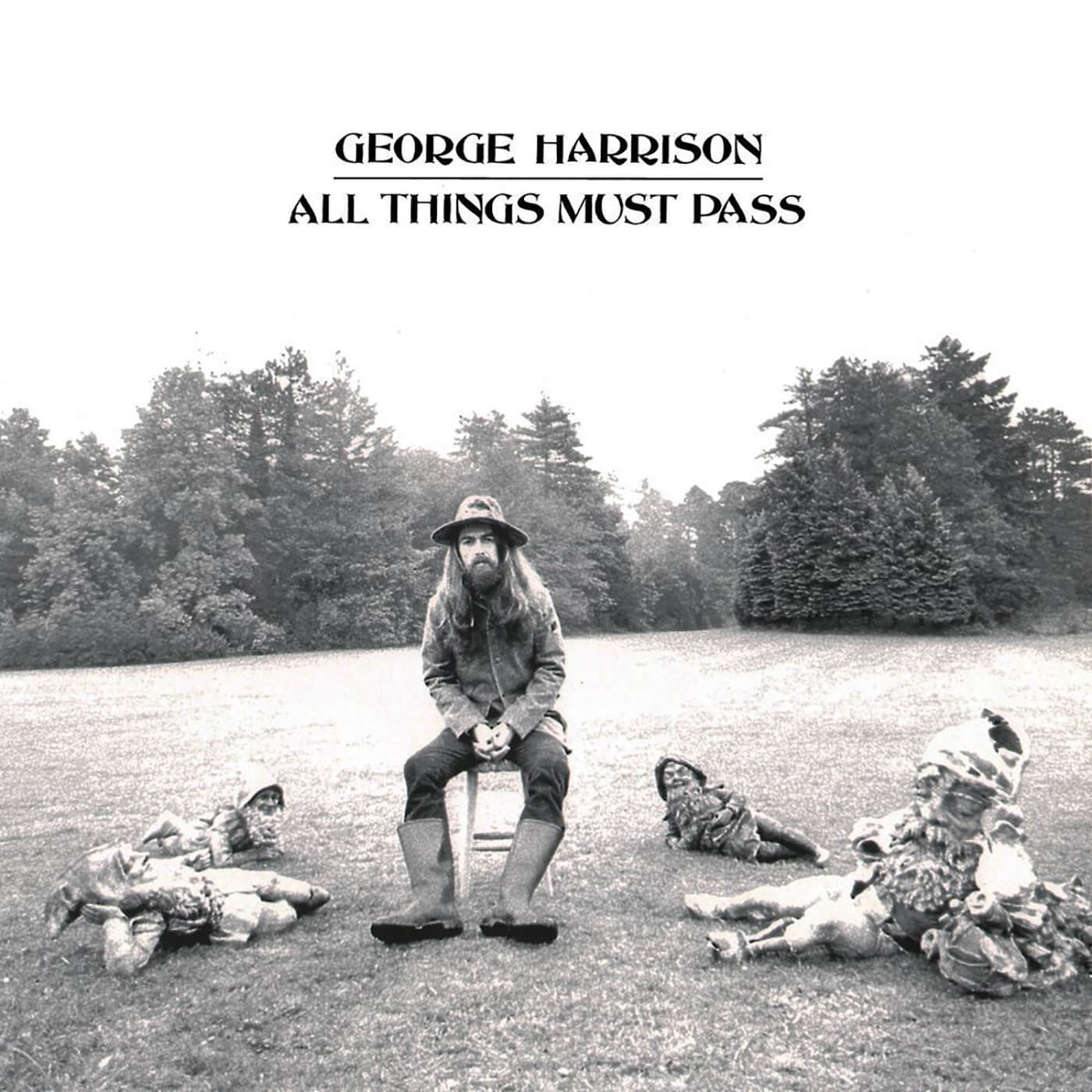

The Genius Of… All Things Must Pass by George Harrison

When The Beatles split in 1970, the question in everyone’s lips and ears was: which of these masterful songwriters would deliver the finest solo record? John Lennon or Paul McCartney? It turned out the answer was George Harrison.

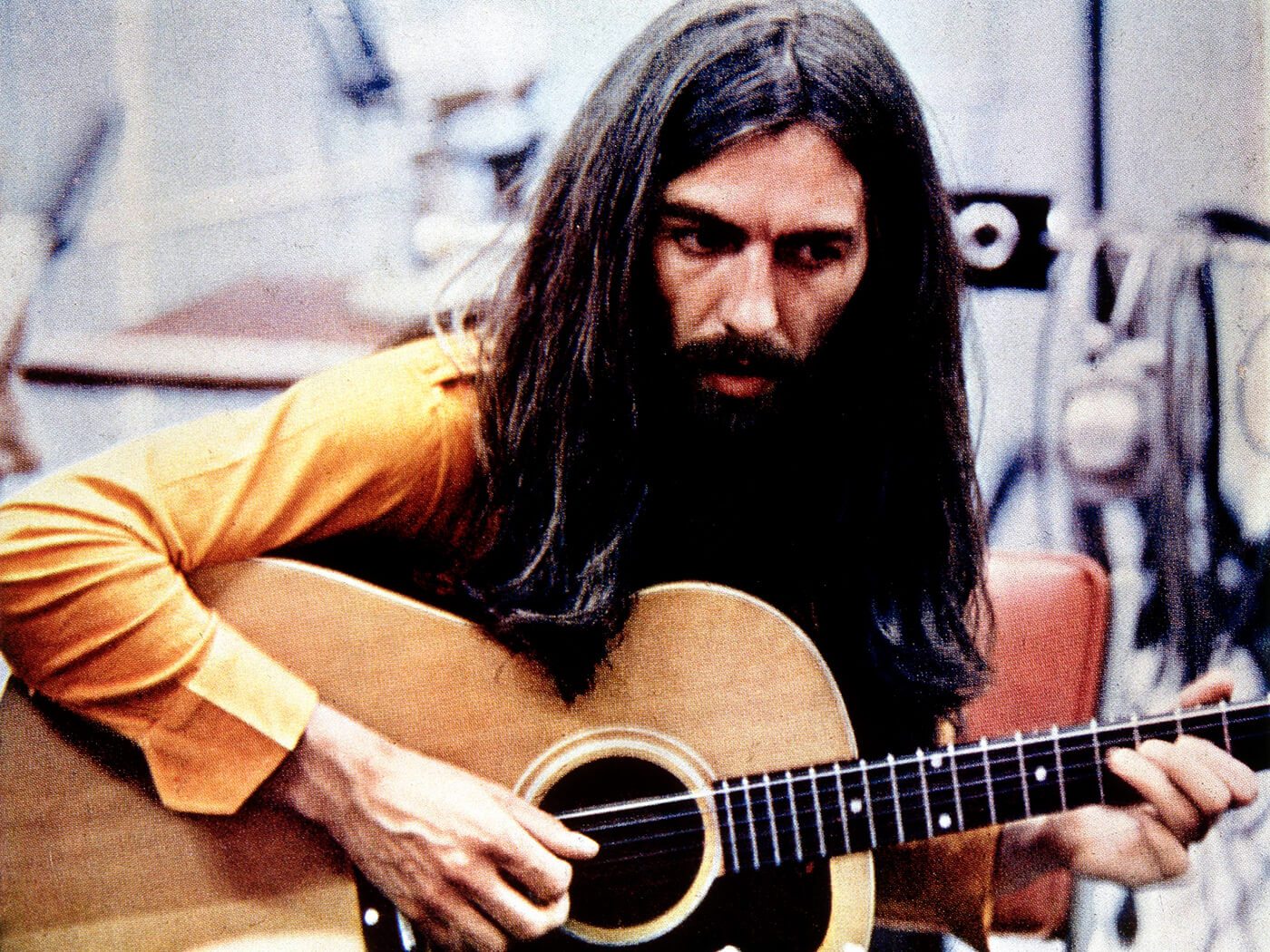

Image: GAB Archive / Redferns

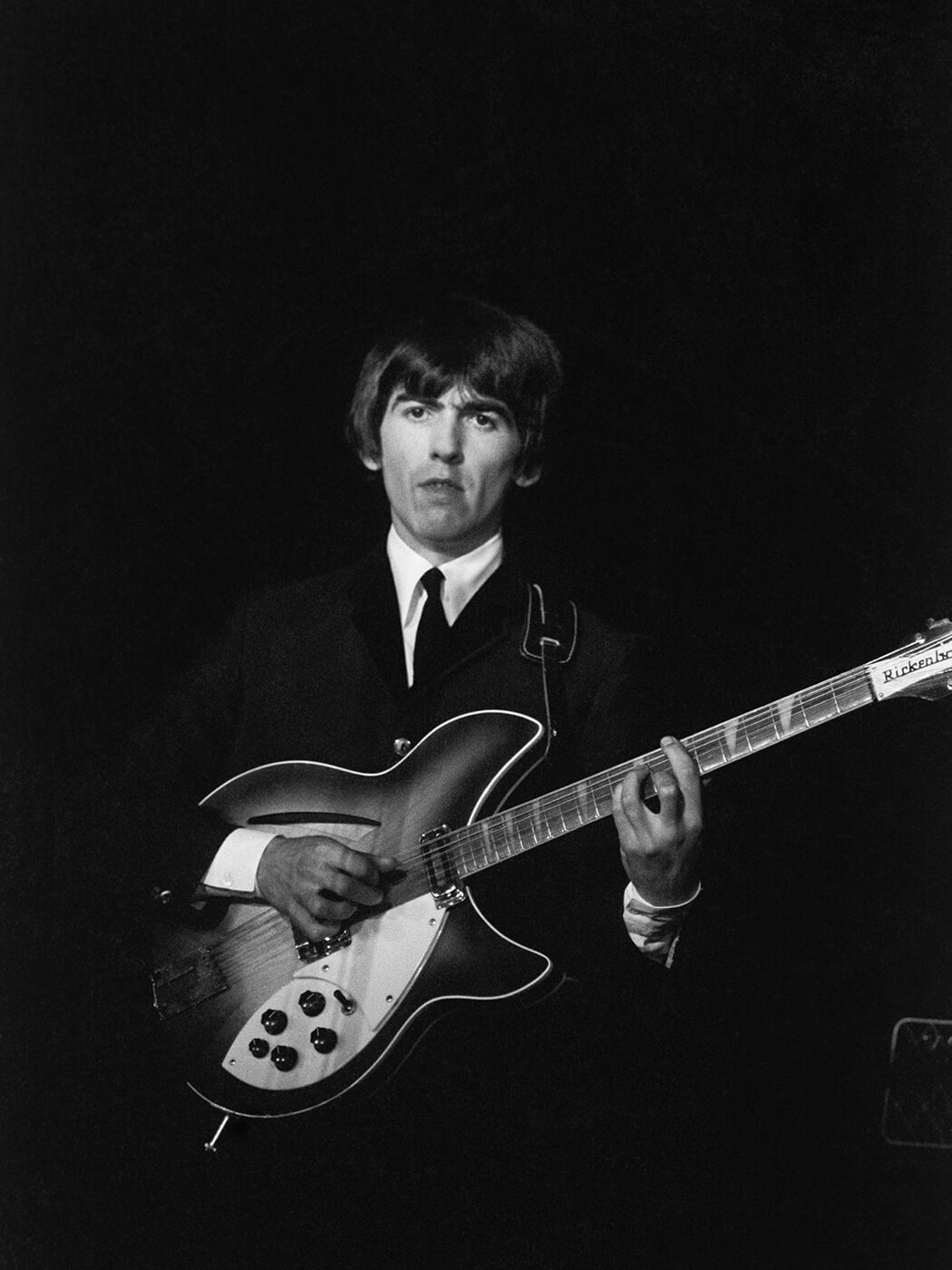

It’s always the quiet ones…

Even in the anarchic annals of rock music, The Beatles’ split in 1970 was a messy affair. Paul McCartney was the first to issue a proper press release that he was “no longer working with the band” yet the four would still record under The Beatles brand to complete the Let It Be sessions. All four were working on solo records: John, Ringo and George Harrison would all contribute to each others’, while McCartney cut his self-titled solo album on home recording equipment at his St John’s Wood home after writing much on retreat in Scotland.

Fabs fans barely knew where to look: in autumn 1969, Lennon had declared, “The trouble is we’ve got too much material. Now that George is writing a lot, we could put out a double album every month…” yet this was clearly not going to happen with antagonism rising. McCartney would later describe that a wholly shared Fabs “wasn’t the right balance” and was “too democratic for its own good.”

When the serious rancour became clear, it was assumed that Lennon vs McCartney would be the narrative. But it turns out George Harrison actually had the most to say…

Diversions with Dylan… to life beyond The Beatles

The roots of All Things Must Pass were planted when Harrison in November 1968 established his long-lasting friendship with Bob Dylan, while staying in Woodstock. The two wrote I’d Have You Anytime together, and although Harrison’s solo songwriting was starting to flourish in The Beatles, it seemed the involvement/blessing of a figure as legendary as Dylan validated George’s efforts.

He was quickly stockpiling songs: George had tried to get the other Beatles interested in All Things Must Pass, Hear Me Lord and the beautiful Let It Down, during rehearsals for the proposed Get Back album (later finished and released as Let It Be) but, perhaps thankfully, they didn’t see them as “Beatles songs.” Or it seems Paul McCartney specifically did not, as Lennon soon stated he was more than happy with more George. Whatever.

The foursome did all approve of Old Brown Shoe and Something, as we know, but All Things Must Pass was never pursued beyond the demo version that can be heard on Anthology 3. Perhaps the double-meaning – a musing of the transient nature of existence that doubled as a commentary on the fracturing Fabs – touched a raw nerve…

It was, possibly in frustration as much as anything, that Harrison played Phil Spector his extensive demos in early 1970. Back then, Spector was simply a celebrated if reclusive record producer, who had not yet earned the ire of Beatles fans for his overdubs and arrangement changes on the posthumous Let It Be, nor that of society in general for his future criminal acts. Maybe Harrison simply thought Spector was a conduit for moving forward, as in Camp Beatles all things were passing quickly.

At a January 1970 lunch to discuss work on Get Back (aka Let It Be), rows erupted: Harrison was frustrated at what he saw as Lennon’s lack of engagement in the project, though Lennon’s increasing heroin problems probably explained that. Ringo Starr later reiterated that Harrison had grown tired of McCartney “dominating” him. George actually announced to his fellow Beatles over lunch that he was leaving – “see you round the clubs” – but was also persuaded to remain to complete the Get Back (Let It Be) songs.

Peter Jackson’s forthcoming Get Back rockumentary (due August 2021) will attempt to show that the last days of The Beatles weren’t all disharmony, and may restore some balance. But, at the time, Harrison had a clear choice: he was writing with Bob Dylan, he’d established new playing partners via his work with Eric Clapton and Delaney & Bonnie, and Phil Spector was “amazed” at the George songs The Beatles were rejecting. Spector also couldn’t believe the sheer number of demos he heard at Harrison’s Friar Park home. “It was endless!” the co-producer later recalled. “He had literally hundreds of songs and each one was better than the rest. He had all this emotion built up when it was released to me.”

Sure, George could have another torturous meeting with The Beatles about The Beatles, when the rest were already plotting solo albums anyway. Or…

Come together

Official recording for All Things Must Pass began in May 1970. As voice, songwriter and a goddamn Beatle, George Harrison was obviously to be the name in lights, but the album truly boasted an extraordinary supporting cast. This seemed typical of George, where friendship and collaboration ruled over everything. An example? To assess whether Jeff Lynne was a suitable co-producer for his 1987 Cloud Nine album, the first thing Harrison suggested was a three-week holiday together in Australia. Friendship sealed, only then the album could be made.

For All Things Must Pass, George called upon his friend Clapton and the other musicians who also played with Delaney & Bonnie, including ex-Traffic guitarist Dave Mason. Clapton wasn’t credited for contractual reasons, except on the third disc in the UK, but he is all over All Things Must Pass. So are future Derek & The Dominos members (and Delaney & Bonnie sidekicks) Carl Radle, Jim Gordon and Bobby Whitlock.

In Pattie Boyd, George and Eric shared romantic interests. So, one may joke, why not bands? Other star contributors included Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, an uncredited Peter Frampton, and bassist Klaus Voormann, artist for the cover of The Beatles’ Revolver and a friend from Hamburg days. Members of Apple signings Badfinger also played acoustic guitars and helped to create Spector’s famed “wall of sound” sonics: on some of the Abbey Road-cut tracks there are as many as five live guitars.

On keyboards, there’s also Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker and Spooky Tooth’s Gary Wright. Classical composer/arranger John Barham was someone Harrison had met via his friendship with Ravi Shankar, and who’d also both played on Harrison’s previous Wonderwall Music.

As well as Ringo and future Yes man (and member of the Plastic Ono Band) Alan White on drums, a young pre-Genesis Phil Collins had a bash on some congas (apparently unused); and Cream/Blind Faith’s Ginger Baker plays on the jam, I Remember Jeep. Harrison flew in Dylan sidekick Pete Drake from Nashville to play pedal steel. Voormann later said, “You could feel after the first few sessions that it was going to be a great album.”

In stark contrast to The Beatles at the end, the recording of All Things Must Pass was characterised by collaboration and an all-comers-welcome philosophy. John Barham opined that Harrison’s preference was always “letting the players find themselves in each song.”

Although not everyone was welcome, in truth. When John Lennon and Yoko Ono turned up asking about progress, drummer Alan Wright recalled Harrison’s discomfort: “His vibe was icy as he bluntly remarked, ‘What are you doing here?’ It was a very tense moment…” Understandable. Not long before, The Beatles baulked at recording too many Harrison songs. Now they wanted to check he could record them himself? Even so, in keeping with the massive roll-call of (sometimes uncredited) players on All Things Must Pass, some still believe Lennon actually did play on it – the lyrics to the joke track It’s Johnny’s Birthday go “It’s so nice to have you back to be our guest”…

Springboard for the 70s

As much as its own cosmic swirl, All Things Must Pass acted like a signpost for the passing of the 60s and the incoming decade. Harrison’s friendship with Dylan had bolstered Bob’s decision to make a comeback performance at the Isle Of Wight festival in 1969, after his debilitating motorcycle crash of 1966. Behind That Locked Door, one of Harrison’s most affecting ballads, is actually written at Dylan and an ode of support to a new but lasting friendship (“Please forget those teardrops, Let me take them from you”). Dylan returned the favour in 1971, lending weight to Harrison’s Concert For Bangladesh, itself the first ‘rock benefit’.

The recording together of Clapton and Delaney and Bonnie’s backing band laid the foundations for Derek & The Dominos. “We made our bones, really, on that album with George”, Clapton confirmed in 1990, saying he and his new American friends had “no game plan” other than living at EC’s Surrey house Hurtwood Edge, “getting stoned, and playing and semi-writing songs.” All Things Must Pass galvanised them. The inspiration even flowed on a micro level: Pete Drake was a pioneer of using a talkbox with his pedal steel and Peter Frampton nicked the idea from the ATMP sessions for his mid-70s breakthrough (Show Me The Way).

Then, of course, there were the songs. My Sweet Lord was a masterstroke of sacrament-by-stealth songwriting and a landmark in introducing Eastern philosophies into mainstream Western pop. It also introduced Harrison’s signature slide playing. In his book I Me Mine, Harrison wrote, “I thought a lot about whether to do My Sweet Lord� or not, because I would be committing myself publicly and I anticipated that a lot of people might get weird about it… I wanted to show that ‘Hallelujah’ and ‘Hare Krishna’ are quite the same thing.”

The more solemn Beware Of Darkness, although sounding more portentous, is another standout based on Harrison’s devotion to the Hare Krishna tradition. In it he warns of corrupting con men (“soft shoe shufflers”), politicians (“greedy leaders”) and pop idols of little substance (“falling swingers”). All wrapped in a composition of bold originality, harmonic movement from the key of C♯m to D major to C major. English musicologist Wilfrid Mellers later noted how it shouldn’t work, but does because it “creates the ‘aimless’ wandering of ‘each unconscious sufferer’”. Far out. As Harrison himself insisted after the epic album’s release, “Music should be used for the perception of God, not jitterbugging…”

An older song addressing reincarnation, Art Of Dying, dated back to 1966. The closest Harrison ever got to hard rock, it’s a full-on Spector kitchen sink production emboldened by sparkling wah soloing by Clapton. How The Beatles came to reject this song – assuming they did – is baffling. Maybe Harrison thought better than to even offer it to The Beatles in three whole years: “at that time I thought it was too far out,” he’d said in happier Fabs times. His I Me Mine book later revealed an early lyric was: “There’ll come a time when all of us must leave here, Then nothing Mr Epstein can do will keep me here with you.”

Outward-looking and dizzyingly technicolour, All Things Must Pass was a stark contrast to the introverted leanings of Lennon and McCartney’s first solo efforts. Even the Apple Jam blues-rock improvs of Sides 5 and 6 (in old money) are endlessly listenable and straight-out fun for musos.

Its gushing of creativity even survived troubled times for Harrison: mid-1970 recording was interrupted as he tended to his dying mother, Louise, back in Liverpool. George’s mother had always been a rock: she had bought him his first guitar, and her fandom of the Radio India programme would help nurture her son’s own sensibilities. As Harrison’s then-wife Pattie Boyd noted about Louise’s death during All Things Must Pass, “All she wanted for her children is that they should be happy, and she recognised that nothing made George quite as happy as making music.” And death would not stop George.

It’s true that some of Spector’s production is over-egged at times (“I grew to like it” Harrison pointedly remarked in the 70s: later, he said he “couldn’t stand” reverb) and subsequent reissues tempered some of the mix bombast. But George essentially self-produced much of the original himself anyway. Spector’s need for copious amounts of brandy to operate at full tilt was, perhaps, a blessing in the end: he didn’t get his hands on everything. Neither did Clapton’s infatuation with Pattie Boyd derail Harrison’s righteous path.

Such details and pitfalls are for those who already know this staggering album. The first triple-album ever. An album of spirituality, honesty, wit and simply great ensemble playing. All majestically conducted by ‘the quiet Beatle’.

A new mix of the title track was released for its 50th anniversary, and new (potentially de-Spector-ed?) mix of the whole album is on the cards for 2021, but in whichever mix flavour, All Things Must Pass was a high George Harrison would never reach again.

As Cracked.com’s Adam Tod Brown wryly wrote in 2013: “If anyone ever tells you there is a better Beatles solo album than All Things Must Pass, congratulations, you’ve probably just met Paul McCartney.”

This was George Harrison, after years of clipped wings, now free as a bird.

Infobox

George Harrison, All Things Must Pass (Apple, 1970)

Selected Condensed Credits

- George Harrison – lead vocals, electric and acoustic guitars, dobro, harmonica, Moog synthesizer, harmonium, backing vocals

- Eric Clapton – electric and acoustic guitars, backing vocals

- Alan White – drums, vibraphone

- Bobby Whitlock – organ, harmonium, piano, tubular bells, backing vocals

- Carl Radle – bass

- Klaus Voormann – bass, electric guitar

- Dave Mason – electric and acoustic guitars

- Pete Ham, Tom Evans, Joey Molland (Badfinger) – acoustic guitars

- Billy Preston, Gary Wright, Tony Ashton, Gary Brooker – keyboards

- Jim Gordon, Ringo Starr, Ginger Baker – drums and percussion

- Jim Price – trumpet, trombone

- Bobby Keys – saxophones

- Pete Drake – pedal steel

- Peter Frampton – acoustic guitars (specifically on the Pete Drake tracks)

- John Barham – orchestral arrangements, choral arrangements, harmonium, vibraphone

Standout guitar moment

Art Of Dying

For more music reviews, click here.